Introduction

This article, as the title reveals, will discuss the way the Levantines are described in the travel literature of the second half of the 19th century. By travel literature I define the travel guide books that were published during this period and also the texts of travelers, British, French and Germans, who visited the Levant and especially the region of Izmir, and which I had the chance to review.

Timeframe & location

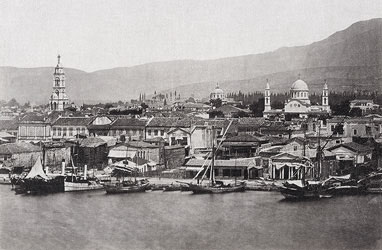

Let me start by justifying my preference in ‘where’ and ‘when’. 19th century Izmir, along with Pera in Istanbul, was truly a model Levantine port-town. Its European characteristics, routed deeply in the past 200 years, occupied the greatest portion of local urban, economic and social life, thus allowing travelers to draw with words pictures that described it as Marseille or Paris of the East. All these characteristics were at their peak in the second half of the 19th century. The city experienced an unprecedented growth in every aspect. Its shape changed with the construction of Quay and the enlargement of main streets, the introduction of facilities such as railway (1858), gas (1862) and electricity (1888). The political framework, with the proclamations of Hatt-i Sharif (1839), Hatt-i Humayoun (1856), the creation of catholic and protestant millets in 1831 and 1850 respectively, along with the long-established capitulation acts ensured the prosperity of the city’s inhabitants, Levantines included.

Identity

It is exactly in this period that the Levantines show up in travel literature as a distinct demographic entity. However, that does not necessarily mean they could be easily described. When it came to distinguish the Levantines from the other communities, several terms applied. The ones most frequently used were ‘Europeans’ and ‘Catholics’. In the travelers’ eyes a Levantine was either a descendant of European emigrants that settled in the Ottoman Empire many generations ago and gradually cut off the ties with the mother country, or an ottoman subject, mostly Greek or Armenian, that married to a European or Levantine. In terms of religion a Levantine was mainly catholic, protestant or even greek-orthodox, provided that he was the offspring of a marriage like the ones already mentioned. For the local population it was much simpler both foreigners and settlers to be called ‘Franks’. The very term ‘Levantine’ did not seem to be very popular. Not all visitors were comfortable with this blurry image. In an era when the European countries based their existence on stereotypes, national awareness and ethnic purity, the characteristics of the Levantines placed them on the margins of West and East, not really fitting in to any of both. That explains perhaps why there are descriptions from travelers such as Rupprecht the Crown Prince of Bavaria in 1894 that are not at all flattering: ‘…they are a mixture of all Mediterranean races, oriental in mentality but polished with European varnish, stateless, frivolous, voluble and light-minded…’. Having said these, he continues in a surprisingly different tone by praising the Levantine women: ‘…amongst them a man often meets dazzling beauty. They appear in the street in the most elegant Parisian dresses, but on the contrary in the house they dress up with negligence…’

Language

The lingual environment was equally diverse. In Izmir you could listen people speaking a dozen different European languages, among which French, English, Italian and Greek prevailed. This situation is vividly illustrated by Frederick Millingen also known as Osman Bey, an Englishman who converted to Islam and became an Ottoman officer, who wrote: ‘…a Levantine family could travel around the world without moving from its place…’. The Levantine pronunciation does not escape uncriticized. Deschamps in 1890 writes: ‘…as the Levantine women walk on by, you can hear them discussing, asking and responding, in strange French: recent neologisms with old-fashioned expressions of the old merchants who left Marseille or Toulon for the long voyage towards Izmir. They close their phrases with abrupt changes of intonation, syllables come out faster by the sudden use of Provencial accent, the ‘Rs’ roll in the flow of the speech like pebbles swept along by the torrent…’

Statistics

Although it is difficult to calculate the exact population of the Levantines in the Near East, due to the lack of official census, in cities with thriving communities such as Izmir, the accounts of travelers give us some very indicative figures:

The actual figure of the Levantines in Izmir does not seem to change dramatically over the years but still, the percentage tends to decline, mainly due to the rise of other ethnic groups, predominantly of the Greeks.

Living space

The Levantine dwellings were situated on the part of Izmir that was most convenient for their commercial activities. Consulates, warehouses and lodgings formed a separate neighborhood that stretched along the sea front and the harbour, called the Frankish or European quarter with its main thoroughfare, the Frank Street, officially known as Sultaniye Caddesi. The advantage of combining housing and shops or warehouses in a single structure that also included a wharf at the water side created a picturesque sight for the visitors who could not help but admire the enterprising spirit of their owners. This picture was about to change dramatically after the completion of Quay in 1874, when the city expanded towards the sea and new luxurious edifices such as clubs, theaters and hotels were erected on the sea front. By then, the Frankish quarter was deprived of many of its most prominent residents that preferred to build new houses on the Quay and villas on the suburbs just like the foreign consuls did before them: the French in Bournabat, the Dutch in Sevdikoy and the English in Boudjah. There they had plenty of space for recreation, especially during the summer, shelter from epidemicies that often broke out and the opportunity to display their wealth.

Well-being

Upon their arrival in Izmir, a foreigner would normally seek the company of a Levantine. In fact, in the days where there were only few and modest boarding houses or hotels, visitors from Europe were accommodated in Levantine houses and in a sense felt like home. Paul Eudel in 1885 describes a dinner that Mr. and Mrs. Cramer invited him to: ‘…They are definitely friendly people. They make us with great cordiality the honor of a great meal admirably served. The copious menu after the regular appetizers included a beautiful fish with mayonnaise, meat fillet, artichokes in oil, a cream cake, seedless Izmir raisins, equally delicious local oranges, oven baked figs, all these accompanied with an excellent home-made bread and a wine from Cyprus called Commanderie that was quite pleasant with a small taste of tar…’

Professional status

Travelers also make special note of the fact that the members of the Levantine community were rather well-off. They particularly mention their unique legal status that relieved them from direct taxation and placed them to the jurisdiction of their consulates. They also give us accounts of their professions. Deschamps describes their evening promenade along the Quay: ‘….You see them all, consular officers, Swiss bankers, German exporters, Austrian tailors, English flour manufacturers, Italian brokers, Hungarian bureaucrats, Dutch fig traders, Armenian suppliers, Greek bankers, not to mention the old notaries and treasurers that fled from their countries for unknown reasons and offer handsomely paid lessons of their mother tongues …’

Scherzer who writes in 1880 adds: ‘…It is typical for the Franks to make partnerships with the European traders and shipping agents, enjoying a professional freedom in doing a job best fitting their skills. For those who chose to become merchants, competition with the locals was inevitable, especially because the latter were deceitful and used means such as intrigue in order to misappropriate their fortune. While a few of them practiced law, medicine or engineering, local trade was almost a Levantine monopoly…’.

Rupprecht again, give us more details on the Levantine community’s internal affairs where there seemed to be a competition in terms of wealth, commercial deals and public works, with the two main rivals being the English and the Germans: ‘…The richest were the English who were living in mansions at the suburb of Bournabat. Lately, German entrepreneurs are competing with them throughout Anatolia, especially on the railway construction where they took the lead because they content with smaller profit, show more respect for the Ottoman government’s instructions and do not have political goals….’

Their professional and financial status led to a widely acknowledged and respected higher social ranking that no other group of foreigners such as the Arabs or the Persians ever enjoyed. Moreover, the European culture and tolerance that they demonstrated is mentioned by the travelers as quite influential on the overall progress of the Ottoman state, penetrating all social classes.

Culture

Levantines also expressed a keen interest in history and art. The travel guides Murray (1873) and Baedeker (1905) suggest to their scholarly readers that the best collections of works of art, antiquites, ancient coins and medals were owned by persons such as James Whittall and Paul Gaudin, the director of Izmir-Cassaba railway who owned among others a fine collection of the famous Smyrna terracotta figurines that ended up in the Louvre museum. These art lovers were always exchanging, buying and selling thus enlarging their cabinets. This should not come as a surprise if we consider that they were among the few who could afford to finance researches and acquire such treasures. Moreover, all major archaeological excavations that took place in the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the 19th century were conducted by Europeans: Pergamon (Humann et al, 1878-1886), Troy (Schliemann, 1868-1879), Miletus (Rayet, 1873) and Ephesus (Wood, 1863-1874). Charles Thomas Newton writes: ‘…at Caravan Bridge a marble lion was found in 1852, which probably marks the situation of a tomb. Part of the ground where these antiquities were discovered belongs to Mr. Whittall, who could probably make an excavation on a large scale if he could get a firman. He is very rich and very generous; he gives away immense sums to the poor, and keeps up a very princely style of hospitality at Bournabat…’. For the same reasons plus their knowledge of people and places in the Near East, Levantines also became ideal companions for excursions to sites of archaeological or Christian interest such as the Seven Churches of Asia, a favorite circuit among travelers.

Recreation

Regarding the Levantines’ social life and entertainment habits, Izmir Casinos were institutions that played an important role. The Murray guide informs us that in 1873: ‘…. Smyrna possesses a peculiar institution in its casinos, or family clubs, founded by the English in the last century. Of these only two now exist, the European or English Casino (consisting of Levantines and Armenians), next to the English Consulate, and the Greek Casino (supported by the Greeks). The latter is the superior. A stranger can get admission for three months, on the application of a friend; and, if in the ball-season, receives invitations for the balls for himself and family. A Masonic charity ball is held yearly. The casinos are supported by subscription of members, and have news-room, card-room, billiard-room and a ball-room where two or three balls were given at the carnival time. The persons invited are: each member, and all persons of his family residing under his roof, the widows and orphans of deceased members, and foreign visitors. French fashions and crinoline are predominant among the native women, and there is a great display of wealth and dress. The handsome English Levantines no longer attend the casinos, as they exercise their hospitality in their own houses....’.

In the same year, Izmir also hosted two theaters, Teatro Cammerano and Teatro Euterpe where the Levantines could watch performances of Italian opera, theatrical plays and music concerts by passing celebrities who toured the Orient. Music was also performed in coffee houses such as Kivotos and café santans.

Institutions

Finally, travelers and guidebooks spent many pages on the Levantine institutions of religion, education and social welfare. Churches, schools, orphanages and hospitals, are frequently visited and enumerated by nationality, capacity, and specialty. All major national communities had such institutions for their members, with some being in a better condition than the others. For the visitor their state of preservation is also expressing a sense of national pride, perhaps reflecting upon the degree of influence over the entire Levantine community, in a unique race for primacy. Newton comments: ‘….the British hospital has remained in status quo ever since the breaking up of the Levant Company. It is placed in a miserable, dilapidated old house with bugs as big as black currants….the Dutch hospital – a perfect model of neatness and propriety….the Austrian small but well organized… the French I was assured it was admirable…’

Epilogue

Conclusively, I must admit that I was rather surprised by the wealth of information found in the travel literature, fragments of which I used for the scope of this presentation. Regardless of the authors’ reason for the voyage; pilgrimage, survey, trade, quest for antiquities or even a longing for exoticism, pleasures and adventure, no matter how subjective, inaccurate or biased he may be, still his texts remain a valuable, fascinating source of information especially on the Levantine community, given the fact that so little has been written by its own members. In fact, we should not forget that many of these trips were successful and pleasant because of the existence of the Levantines, who acted as the key to unlock the strange and hostile world of the Eastern interior. There are literary hundreds of books in libraries, and there is a lot to learn by those who were attracted by the Orient and wanted to share with others their experience of the art of traveling. Only a fraction of this material has been reprinted and is widely available mainly through the modern OCR (optical character definition) technique which is quite promising and has already been successfully used.

In the field of Levantine studies, I believe that travel literature if thoroughly studied and combined with other historical sources such as biographies and public archives, can help to compose a panorama of an era that is so close and yet so distant from our own, focusing on people’s stories and yielding colorful descriptions of who they were, how they lived and interacted with the other communities and what they achieved.

Selected bibliography

Note: Achilleas continues to study the history of Smyrna and would appreciate any feedback (achilleasch[at]gmail.com) on the above article or for his work on the ‘Smyrna Timeline’ work, accessible here and explained here:

submission date 2011

submission date 2011

This article, as the title reveals, will discuss the way the Levantines are described in the travel literature of the second half of the 19th century. By travel literature I define the travel guide books that were published during this period and also the texts of travelers, British, French and Germans, who visited the Levant and especially the region of Izmir, and which I had the chance to review.

Travel Guides: Murray’s 1873 |

& Baedekers 1905 |

Examples of 19th century travel books |

>> |

>> |

Timeframe & location

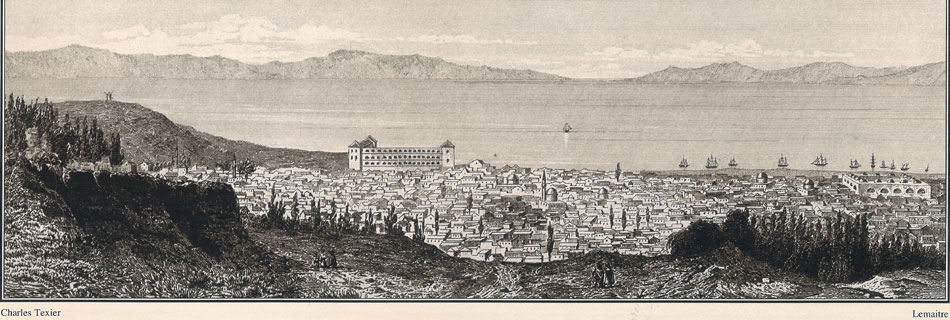

Let me start by justifying my preference in ‘where’ and ‘when’. 19th century Izmir, along with Pera in Istanbul, was truly a model Levantine port-town. Its European characteristics, routed deeply in the past 200 years, occupied the greatest portion of local urban, economic and social life, thus allowing travelers to draw with words pictures that described it as Marseille or Paris of the East. All these characteristics were at their peak in the second half of the 19th century. The city experienced an unprecedented growth in every aspect. Its shape changed with the construction of Quay and the enlargement of main streets, the introduction of facilities such as railway (1858), gas (1862) and electricity (1888). The political framework, with the proclamations of Hatt-i Sharif (1839), Hatt-i Humayoun (1856), the creation of catholic and protestant millets in 1831 and 1850 respectively, along with the long-established capitulation acts ensured the prosperity of the city’s inhabitants, Levantines included.

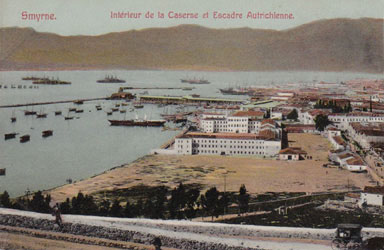

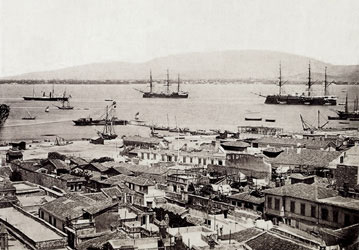

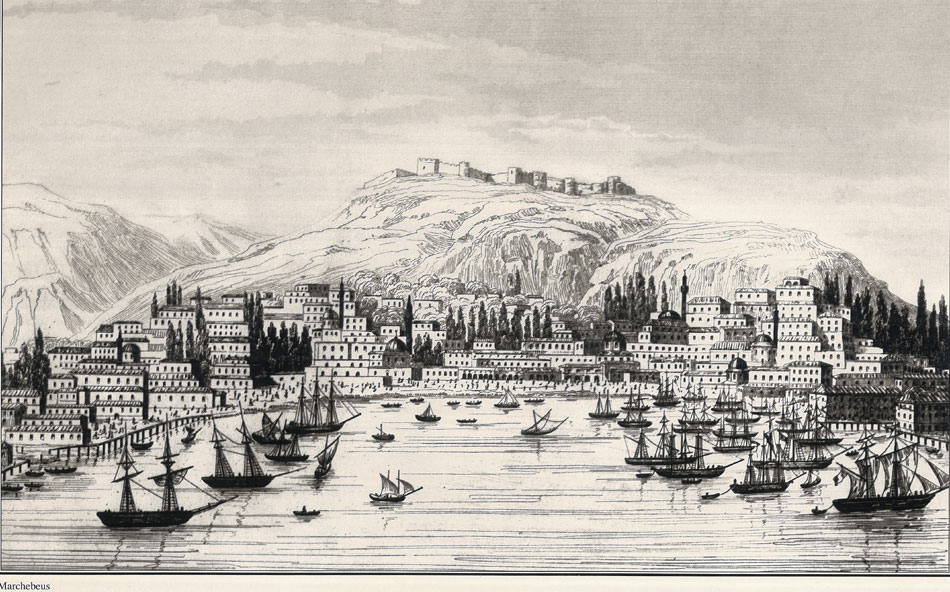

Old harbour of Smyrna, 1865 |

Harbour & barracks, 1865 |

Identity

It is exactly in this period that the Levantines show up in travel literature as a distinct demographic entity. However, that does not necessarily mean they could be easily described. When it came to distinguish the Levantines from the other communities, several terms applied. The ones most frequently used were ‘Europeans’ and ‘Catholics’. In the travelers’ eyes a Levantine was either a descendant of European emigrants that settled in the Ottoman Empire many generations ago and gradually cut off the ties with the mother country, or an ottoman subject, mostly Greek or Armenian, that married to a European or Levantine. In terms of religion a Levantine was mainly catholic, protestant or even greek-orthodox, provided that he was the offspring of a marriage like the ones already mentioned. For the local population it was much simpler both foreigners and settlers to be called ‘Franks’. The very term ‘Levantine’ did not seem to be very popular. Not all visitors were comfortable with this blurry image. In an era when the European countries based their existence on stereotypes, national awareness and ethnic purity, the characteristics of the Levantines placed them on the margins of West and East, not really fitting in to any of both. That explains perhaps why there are descriptions from travelers such as Rupprecht the Crown Prince of Bavaria in 1894 that are not at all flattering: ‘…they are a mixture of all Mediterranean races, oriental in mentality but polished with European varnish, stateless, frivolous, voluble and light-minded…’. Having said these, he continues in a surprisingly different tone by praising the Levantine women: ‘…amongst them a man often meets dazzling beauty. They appear in the street in the most elegant Parisian dresses, but on the contrary in the house they dress up with negligence…’

Construction works at the harbour, 1870 |

Inner harbour and Passport, 1895 |

Language

The lingual environment was equally diverse. In Izmir you could listen people speaking a dozen different European languages, among which French, English, Italian and Greek prevailed. This situation is vividly illustrated by Frederick Millingen also known as Osman Bey, an Englishman who converted to Islam and became an Ottoman officer, who wrote: ‘…a Levantine family could travel around the world without moving from its place…’. The Levantine pronunciation does not escape uncriticized. Deschamps in 1890 writes: ‘…as the Levantine women walk on by, you can hear them discussing, asking and responding, in strange French: recent neologisms with old-fashioned expressions of the old merchants who left Marseille or Toulon for the long voyage towards Izmir. They close their phrases with abrupt changes of intonation, syllables come out faster by the sudden use of Provencial accent, the ‘Rs’ roll in the flow of the speech like pebbles swept along by the torrent…’

Statistics

Although it is difficult to calculate the exact population of the Levantines in the Near East, due to the lack of official census, in cities with thriving communities such as Izmir, the accounts of travelers give us some very indicative figures:

- 25.000 or 17% of the population (Ross, 1844)

- 20.000 or 11% (Slaars, 1868)

- 16.000 or 8% (Murray,1873)

- 25.000 or 13% (Earl Raven, 1886)

The actual figure of the Levantines in Izmir does not seem to change dramatically over the years but still, the percentage tends to decline, mainly due to the rise of other ethnic groups, predominantly of the Greeks.

Promenade on the Quay, 1885 |

The British and Austro-Hungarian Consulates, 1856 |

Living space

The Levantine dwellings were situated on the part of Izmir that was most convenient for their commercial activities. Consulates, warehouses and lodgings formed a separate neighborhood that stretched along the sea front and the harbour, called the Frankish or European quarter with its main thoroughfare, the Frank Street, officially known as Sultaniye Caddesi. The advantage of combining housing and shops or warehouses in a single structure that also included a wharf at the water side created a picturesque sight for the visitors who could not help but admire the enterprising spirit of their owners. This picture was about to change dramatically after the completion of Quay in 1874, when the city expanded towards the sea and new luxurious edifices such as clubs, theaters and hotels were erected on the sea front. By then, the Frankish quarter was deprived of many of its most prominent residents that preferred to build new houses on the Quay and villas on the suburbs just like the foreign consuls did before them: the French in Bournabat, the Dutch in Sevdikoy and the English in Boudjah. There they had plenty of space for recreation, especially during the summer, shelter from epidemicies that often broke out and the opportunity to display their wealth.

Frank Street |

Kramer Place |

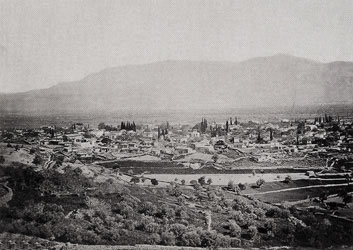

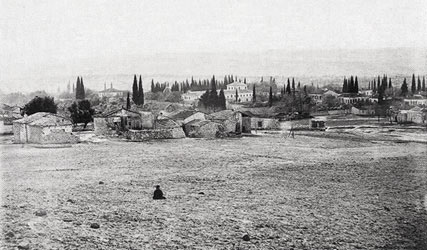

Bournabat, 1880 |

Well-being

Upon their arrival in Izmir, a foreigner would normally seek the company of a Levantine. In fact, in the days where there were only few and modest boarding houses or hotels, visitors from Europe were accommodated in Levantine houses and in a sense felt like home. Paul Eudel in 1885 describes a dinner that Mr. and Mrs. Cramer invited him to: ‘…They are definitely friendly people. They make us with great cordiality the honor of a great meal admirably served. The copious menu after the regular appetizers included a beautiful fish with mayonnaise, meat fillet, artichokes in oil, a cream cake, seedless Izmir raisins, equally delicious local oranges, oven baked figs, all these accompanied with an excellent home-made bread and a wine from Cyprus called Commanderie that was quite pleasant with a small taste of tar…’

Boujah, 1880 |

Hotel de Deux Auguste, 1880 |

Professional status

Travelers also make special note of the fact that the members of the Levantine community were rather well-off. They particularly mention their unique legal status that relieved them from direct taxation and placed them to the jurisdiction of their consulates. They also give us accounts of their professions. Deschamps describes their evening promenade along the Quay: ‘….You see them all, consular officers, Swiss bankers, German exporters, Austrian tailors, English flour manufacturers, Italian brokers, Hungarian bureaucrats, Dutch fig traders, Armenian suppliers, Greek bankers, not to mention the old notaries and treasurers that fled from their countries for unknown reasons and offer handsomely paid lessons of their mother tongues …’

Scherzer who writes in 1880 adds: ‘…It is typical for the Franks to make partnerships with the European traders and shipping agents, enjoying a professional freedom in doing a job best fitting their skills. For those who chose to become merchants, competition with the locals was inevitable, especially because the latter were deceitful and used means such as intrigue in order to misappropriate their fortune. While a few of them practiced law, medicine or engineering, local trade was almost a Levantine monopoly…’.

Rupprecht again, give us more details on the Levantine community’s internal affairs where there seemed to be a competition in terms of wealth, commercial deals and public works, with the two main rivals being the English and the Germans: ‘…The richest were the English who were living in mansions at the suburb of Bournabat. Lately, German entrepreneurs are competing with them throughout Anatolia, especially on the railway construction where they took the lead because they content with smaller profit, show more respect for the Ottoman government’s instructions and do not have political goals….’

Their professional and financial status led to a widely acknowledged and respected higher social ranking that no other group of foreigners such as the Arabs or the Persians ever enjoyed. Moreover, the European culture and tolerance that they demonstrated is mentioned by the travelers as quite influential on the overall progress of the Ottoman state, penetrating all social classes.

Customs, 1880 |

People on the Quay, 1880 |

Culture

Levantines also expressed a keen interest in history and art. The travel guides Murray (1873) and Baedeker (1905) suggest to their scholarly readers that the best collections of works of art, antiquites, ancient coins and medals were owned by persons such as James Whittall and Paul Gaudin, the director of Izmir-Cassaba railway who owned among others a fine collection of the famous Smyrna terracotta figurines that ended up in the Louvre museum. These art lovers were always exchanging, buying and selling thus enlarging their cabinets. This should not come as a surprise if we consider that they were among the few who could afford to finance researches and acquire such treasures. Moreover, all major archaeological excavations that took place in the Ottoman Empire in the second half of the 19th century were conducted by Europeans: Pergamon (Humann et al, 1878-1886), Troy (Schliemann, 1868-1879), Miletus (Rayet, 1873) and Ephesus (Wood, 1863-1874). Charles Thomas Newton writes: ‘…at Caravan Bridge a marble lion was found in 1852, which probably marks the situation of a tomb. Part of the ground where these antiquities were discovered belongs to Mr. Whittall, who could probably make an excavation on a large scale if he could get a firman. He is very rich and very generous; he gives away immense sums to the poor, and keeps up a very princely style of hospitality at Bournabat…’. For the same reasons plus their knowledge of people and places in the Near East, Levantines also became ideal companions for excursions to sites of archaeological or Christian interest such as the Seven Churches of Asia, a favorite circuit among travelers.

Fig workers, 1880 |

Fort on mount Pagus [Kadifekale], 1865 |

Recreation

Regarding the Levantines’ social life and entertainment habits, Izmir Casinos were institutions that played an important role. The Murray guide informs us that in 1873: ‘…. Smyrna possesses a peculiar institution in its casinos, or family clubs, founded by the English in the last century. Of these only two now exist, the European or English Casino (consisting of Levantines and Armenians), next to the English Consulate, and the Greek Casino (supported by the Greeks). The latter is the superior. A stranger can get admission for three months, on the application of a friend; and, if in the ball-season, receives invitations for the balls for himself and family. A Masonic charity ball is held yearly. The casinos are supported by subscription of members, and have news-room, card-room, billiard-room and a ball-room where two or three balls were given at the carnival time. The persons invited are: each member, and all persons of his family residing under his roof, the widows and orphans of deceased members, and foreign visitors. French fashions and crinoline are predominant among the native women, and there is a great display of wealth and dress. The handsome English Levantines no longer attend the casinos, as they exercise their hospitality in their own houses....’.

In the same year, Izmir also hosted two theaters, Teatro Cammerano and Teatro Euterpe where the Levantines could watch performances of Italian opera, theatrical plays and music concerts by passing celebrities who toured the Orient. Music was also performed in coffee houses such as Kivotos and café santans.

Caravan Bridge, 1865 |

Café Eden at Punta |

Institutions

Finally, travelers and guidebooks spent many pages on the Levantine institutions of religion, education and social welfare. Churches, schools, orphanages and hospitals, are frequently visited and enumerated by nationality, capacity, and specialty. All major national communities had such institutions for their members, with some being in a better condition than the others. For the visitor their state of preservation is also expressing a sense of national pride, perhaps reflecting upon the degree of influence over the entire Levantine community, in a unique race for primacy. Newton comments: ‘….the British hospital has remained in status quo ever since the breaking up of the Levant Company. It is placed in a miserable, dilapidated old house with bugs as big as black currants….the Dutch hospital – a perfect model of neatness and propriety….the Austrian small but well organized… the French I was assured it was admirable…’

Epilogue

Conclusively, I must admit that I was rather surprised by the wealth of information found in the travel literature, fragments of which I used for the scope of this presentation. Regardless of the authors’ reason for the voyage; pilgrimage, survey, trade, quest for antiquities or even a longing for exoticism, pleasures and adventure, no matter how subjective, inaccurate or biased he may be, still his texts remain a valuable, fascinating source of information especially on the Levantine community, given the fact that so little has been written by its own members. In fact, we should not forget that many of these trips were successful and pleasant because of the existence of the Levantines, who acted as the key to unlock the strange and hostile world of the Eastern interior. There are literary hundreds of books in libraries, and there is a lot to learn by those who were attracted by the Orient and wanted to share with others their experience of the art of traveling. Only a fraction of this material has been reprinted and is widely available mainly through the modern OCR (optical character definition) technique which is quite promising and has already been successfully used.

In the field of Levantine studies, I believe that travel literature if thoroughly studied and combined with other historical sources such as biographies and public archives, can help to compose a panorama of an era that is so close and yet so distant from our own, focusing on people’s stories and yielding colorful descriptions of who they were, how they lived and interacted with the other communities and what they achieved.

Selected bibliography

BAEDEKER, Karl, Baedekers Konstantinopel und Kleinasien, Leipzig, 1905

DESCHAMPS, Gaston, Sur le routes d’Asie, Paris, 1894

EUDEL, Paul, Constantinople, Smyrne et Athènes: Journal de voyage, Paris, 1885

MURRAY, John, A Handbook for travellers in Constantinople and Turkey in Asia, London, 1873 - google books -

NEWTON, Charles Thomas, Travels & Discoveries in the Levant, Volumes 1 & 2, London, 1865

RUPPRECHT Kronzprinz von Bayern, Reiseerinnerungen aus dem suedosten Europas und dem Orient, Munchen, 1923

SCHERZER, Charles de, Smyrne, Leipzig, 1880

SCHIFFER, Rheinhold, Oriental Panorama: British Travellers in 19th Century Turkey, Amsterdam, 1999

SCHMITT, Oliver Jens, Levantiner, 2005, Munchen

DESCHAMPS, Gaston, Sur le routes d’Asie, Paris, 1894

EUDEL, Paul, Constantinople, Smyrne et Athènes: Journal de voyage, Paris, 1885

MURRAY, John, A Handbook for travellers in Constantinople and Turkey in Asia, London, 1873 - google books -

NEWTON, Charles Thomas, Travels & Discoveries in the Levant, Volumes 1 & 2, London, 1865

RUPPRECHT Kronzprinz von Bayern, Reiseerinnerungen aus dem suedosten Europas und dem Orient, Munchen, 1923

SCHERZER, Charles de, Smyrne, Leipzig, 1880

SCHIFFER, Rheinhold, Oriental Panorama: British Travellers in 19th Century Turkey, Amsterdam, 1999

SCHMITT, Oliver Jens, Levantiner, 2005, Munchen

Note: Achilleas continues to study the history of Smyrna and would appreciate any feedback (achilleasch[at]gmail.com) on the above article or for his work on the ‘Smyrna Timeline’ work, accessible here and explained here:

a variety of Engravings of Smyrna below, by Charles Texier, Marchebeus and Thomas Allom.

|

|

|