In the XVIIIth century the East India Companies of England, France and the Netherlands ruled over many coastal towns and their neighbouring territories in India, Indochina and Indonesia. An early example of such a mixture of trade and politics can be found in the Maona Giustiniani which ruled over the island of Scio (Chios), in the Aegean Sea for more than two centuries, from 1347 to 1566. The name “maona” is of uncertain origin, maybe from the Genovese dialect “mobba” equivalent to union, or derived from the name of a type of ship, but most likely of Arab origin Maounach (=trading company). The origin of the word is therefore tied with this arrangement of families combining to the level of a trade partnership (“lodges”). Such “societies” were loyal to themselves, with their own hierarchy of lordships, maintaining their own armies, and fiscal autonomy and with politics often in contradiction with that espoused by the same Republic from which they originated from. From the fourteenth to the sixteenth century, the history of the island of Chios is intimately bound with that of the Giustiniani family, a nobility from Genoa that assumed the control of this island.

|

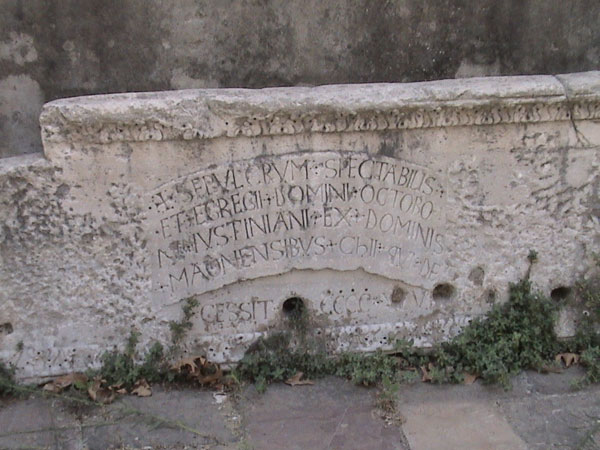

In the XIVth century the Genovese were competing with the Venetians for the control of the trading routes in the Levant and in the Black Sea. Venice had a firm hold on Negroponte [island of Euboea] and Candia [Heraklion, capital of Crete] and Genoa needed a secure trading post along the route to Constantinople. Therefore in 1346 the Republic decided to occupy the island of Scio and the nearby port of Focea (famous port for the alum mineral) on the Asian mainland. Because the finances of the Republic were in very poor health, some rich traders were asked for loans to be repaid after the completion of the expedition. On February 26, 1347 the Republic granted to these traders the revenues of Scio and Focea allowing them to directly manage the exploitation of the two territories for an initial period of 29 years. The traders founded the Maona Giustiniani and later on obtained an extension of the initial “lease”. The noble family Giustiniani as a “Society” based on “actions”, leading to the first stock exchange documented in world history. Twelve Nobles, Genovese Patricians decided a union among us, to form a “society” and to form together a family. They even take away their former names to have a new one: “Giustiniani”: they made “A Campagna”, as if “they were born from the same father and the same mother” (“Compagniam de pecunia non faciam cum aliquo habitante ultra Vultabium et Savignonem et Montem altum, neque ultra Varaginem” from “Leges Genuenses” – year 1157).

|

|

|

|

With these Lords, Giustiniani started a “collegiate”

system of government. Each of the twelve partners having his own allocation

of responsibility: equal was their fortune and equal were their titles.

An example (probably the only) that a noble title could pass from

one to another, not by blood, but to sell their “share” in the society.

The island is famous for its scenery and good climate. Its chief export

is mastic, a gum that exudes from the bark of a tree grown in the

southern part of the island.

Unlike many other Greek towns, Chios was not built on high ground

providing a natural defence; it did not have an acropolis, a citadel

where the inhabitants could put up an effective resistance to the

assaults of an enemy. The Genoese found some Byzantine fortifications,

but eventually decided to build a new set of walls, which would protect

their new acquisition.

Maona Giustiniani promoted farming in Scio and in particular in Kampos,

a plain to the south of the town. Each farm was surrounded by walls,

often rather high, having the objective to minimize the erosion of

the soil due to the meltemi, the strong wind which blows

across the Aegean. The walls and the buildings were erected making

use of Thymiana, a local stone with warm red and yellow hues.

Each farm had a deep well to intercept the flow of abundant underground

waters. Overall the texture of buildings, gates, boundary walls, etc.

is still very consistent and the majority of the modern additions

respect the old architectural patterns.

|

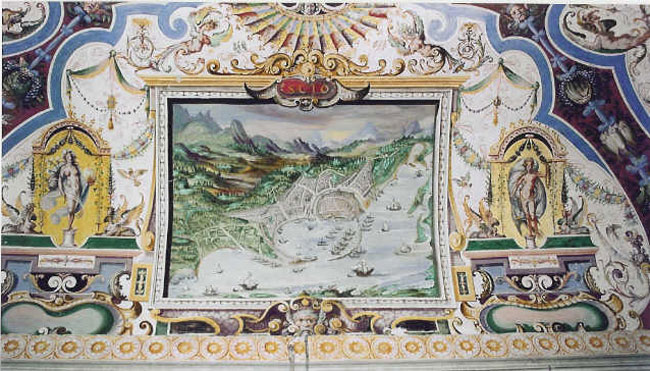

In 1431, a fleet of 30 of Venice’s ships headed by Andrea Mocenigo and Dolfino Venier tightened their siege of Chios. The Maona arranges the defence, besieged in their fortress, with only 300 armed men commanded by Leonardo di Montaldo, but they resists stoically the repeated attacks of the overwhelming enemy forces. On Christmas day in 1431, the defending Genoans, seeing the port only defended with cargo vessels, counterattack the Venetians by outflanking them, thus delivering a powerful victory for the Genoese. The siege of Chios was lifted on 17/1/1432. Andrea De Marini conclusively defeats the Venetians in the Aegean sea on April 1432. Mocenigo and Venier, on returning to Venice are executed, accused of badly managing the attack on the fortress of Chios. By 1432 a state of peace between Genoa and Venice was established, mainly because the Ottoman common enemy made itself more and more pressing, thus the various possessions of these Republics in the Aegean became ever more threatened.

The island of Chios was governed from the Maona Giustiniani with two councils: “large Council” and a “small Council of the forty”. Beyond the citadel there were 36 fortified castles. The fifteen castles of Chios beyond the Citadel were: Colla, Calomoti, Cardamile, Lamista, Late, Lecovere, Melanete, Pannuccelli, Perparea, Pigri, Pitio, Sant’Elena, S.Giuliano, Valisso (the most fortified) and Vigo. The island of Chios had an independent bishop, the first one was Manfredo De Coronato who in 1363 was succeeded either by the Pallavicini family or by the Giustiniani family until 1879 (Ignazio Giustiniani). The island had numerous churches, convents and hospitals. One of them was also established in Rome for the Maonesi community there, founded in the 1530 by the bishop Benedict Giustiniani. The population of Chios in the XVth century oscillated between 90,000 and 120,000 inhabitants, having a constant increment with the Christians escaping the ever powerful Ottomans. The dominant rank of the island, was the Giustiniani together with their family relations. Later arrivals, were effectively second class, the “Burgenses”, of Latin blood, nearly all from Genoa, traders or small large estate owners in search of new pastures. Rising up the social scale was through becoming related with the Giustiniani (such as the families of Paterio, Navone, Sanginbene, Campanaro, Ciprocci, Cavallini, Coresio). The third socio-economic level were the “Greek archons”, the population of Greek blood engaged at best in small commerce. The fourth level were persons of Greek origin engaged in manual labour, such as connected with mastic and agriculture. The fifth level the Jews, were often involved in usury, were forced to live in the “ghetto” (they were only allowed to exit during the Saint week), to carry a yellow hat, and in certain times of the year had to acknowledge their subjection and submission to the Giustiniani. The sixth level were the foreigneirs not resident (long term) in the island.

In 1453 when the Ottoman Sultan Mehmet II launched his attack against the walls of Constantinople, a Genoese contingent of volunteers from Chios went to Constantinople to join the limited forces of the Emperor. They were led by a gallant young soldier called Giovanni Giustiniani Longo, who played a crucial role in the siege of the city, until being wounded during the final Ottoman assault, that signalled the forthcoming defeat. The Genoese fortifications of Scio included a very deep moat, now a dusty parking-lot, which isolated the town with the exception of one point of access. After the fall of Constantinople, Genoa had to come to terms with the Sultan. Because the Sultan rightly saw that only Venice could actually challenge his expansion aims, he preferred to establish a good relationship with Genoa, so Scio was not threatened by the Ottomans. However, Maona Giustiniani had to agree to yearly pay the Sultan a large amount of gold and to grant him a supply of mastic, a gum exuding from the bark of a tree grown in the southern part of the island. However, the Ottomans, at all costs tried to take definite control of the islands. On the pretext of militarily support to the credit pretension of the Genovese nobleman Francisco Drapperio, in the spring of 1455, a powerful Ottoman fleet anchors offshore of Chios. The Turkish admiral Hansabeg saw the good fortifications of the island, thus judging that it was not worth the risk of an attack. The Genovese Republic at the time was engaged in a war with Alfonso of Aragon, thus not being able to help its far colonies, was limited to arm two galleys with 800 men, commanded by Peter Giustiniani (still mayor of Soverein of Malta during Lepanto, a battle against Turks on October 1571) and appealed for aid to the Pope and the King of England, Henry VI. In the autumn of 1455, 20 Turkish triremes (war galley with 3 sets of rowers) commanded by Junusberg, moved towards Chios, however a storm forces them to disperse, but they still capture without a fight New Focea on 24 December 1455 and the island of Lesbos. In 1481 the Giustiniani abandon the island of Samos and leave Nicaria to the Knights of S. Giovanni, which already had to abandon the island of Kos. These islands lacking ports and nearly deserted, were of insufficient interest to the Giustiniani as well as the Turks. Also Genoa begins to fear the power of the Giustiniani, so on 2 March 1558, a plenipotentiary to the Doge in Constantinople, Francisco de Franchi Torturino, negotiates to yield, the exploitation of Chios by the Turks.

|

|

|

The heads of the Maona were imprisoned in Crimea, where many died, the survivors, with the intercession of the French ambassador, in 1567 were granted return to Genoa. Most of them returned to Chios, their fatherland. There was still a bishop of Chios in the XIXth century: Ignazio in 1830 and another with the same name in 1879. Today there aren’t any people with this surname in Chios. The old dominions of the Giustiniani in the Dodecanese, under Turkish agression, soon after went to ruin. Chios was reduced to a den of thieves and pirates. The few Latins that remained were imprisoned by the Ottomans. The greater part of the remaining population were plebeians. All the churches of the island were destroyed except the convent of the Franciscans and the “chapel” of the Dominicans.

The wealthiest Giustiniani families chose to leave the island, to Genoa, as well as escaping to Rome, Ancona, Amatrice, Messina, Palermo, Caprarica of Lecce, Smyrna, Alexandria, and generally all around the Mediterranean area.

One on the Giustiniani who survived was Giuseppe Giustiniani who moved to Rome. In that city his brother in law was Cardinal Vincenzo Giustiniani who introduced him to the papal court. He married his three daughters to members of the Roman aristocracy and his son Benedetto became a cardinal in 1586. In 1590 he bought what today is known as Palazzo Giustiniani2 (now seat of the Senate of the Italian Republic) and in 1595 the fief of Bassano Romano (the old name was “Bassano di Sutri”), the estate within which they had their “villa” (palace with a large garden). He increased the fame and celebrity of Giustiniani’s family, being the patron of Caravaggio, the finest painter of his time. The renowned collections of Caravaggio master pieces are today scattered in museums and in private collections around the world. When his highness the Prince of Bassano Romano, Marquees Vincenzo Giustiniani died, he decided (by testament to bequeath) and left a part of his riches to his descendants Giustiniani. It’s usual that in the testaments of the lords of Giustiniani, a part of the riches went to all Giustiniani, particularly if their weren’t any direct descendents. In particular in the Marquees Vincenzo Giustiniani’s testament, after a very long contentious case that lasted from 1631 to 1953, a judgement decided that those who could prove to be a descendant of the first “twelve Giustiniani” and to have an ancestor in the gold book of the nobles of Genoa, or the lords of Chios, was heir to part of the estate. At the end, it was worked out that there were 288 heirs and heiresses divided in 12 lines. But most of heirs didn’t participate in this contention and probably still today don’t know to be heirs of this family.

It’s import to emphasize that the genovese nobility is a republican nobility, nobles as persons who participated in the city government, not as feudal nobility as like we are accustoms to mean.

Now, I’m engaging in maintaining interest and investigating the history of this family. You can find a lot of information on my web site in Italian (www.giustiniani.info). On April 17, 2004, I organized in Bassano Romano (Viterbo - Italy), with the patronage of Senate of the Italian Republic and The Sovereign Military Order of Malta, in collaboration with the Communal Administration and the Italian-Greek Alliance, a convention: “From Giustiniani to the Eurpean Union: a continuous dialogue”. In this event a wide range of people participated, including teachers and administrators of the Italians Municipalitys of: Mirano (Venice), Ortona (Chieti), Caprarica (Lecce), Amelia (Terni), Lari and Fauglia (Pisa), the French Municipality of Bastia (island of Corsica), and the Greeks in the Municipalities of Chios, Homiroupolis, Aghios Minas and Ionias.

The various family relations have analyzed the history of Giustiniani during the centuries, from republic of the sea during XIV century in the Levant, the arts collections of the XVIth century of the famous patron Vincenzo and Benedetto Giustiniani* (both born in Chios), and the architecture of the Giustiniani’s palaces around Mediterranean area. A long travel between history and a culture in order to re-establish, in the European spirit, the old ties among people of various cultures and society.

The long term aim of this initiative is to set up an organisation covering a range of subjects, with the purpose of safeguarding the historical-cultural assets, for the full appreciation of family palaces, objects, and memories of the Giustiniani family.

In the summer of 2005, a new project about Giustiniani family was started in Chios, a co-production of Italian-French and Greek participants, to create a cultural documentary movie about the long travel of the Giustiniani family around Mediterranea area. The final product will be in French and is due to finish later in 2006.

On December 1st, 2005, after 18 months of work, a symposium (pdf info in Italian) was held in celebration of this family, in the prestigious Giustiniani Palace in Rome, and a book of this convention was proposed. This book (in Italian with a section in Greek) is being prepared, post-convention, using the various contributions by the speakers (historians, university professors, administrators of the municipalities…). Now I hope there will be other occasions to continue the “dialogue” concerning the history of Giustiniani.

|

Notes:

1. Legend is the half-way house between history and fable. Many genealogical researches have been commissioned by rich people, hopeful that their uncertain origins, with surnames close to those of famous historical personages, such as a Roman or celtic emperor, in order to credit himself a part in the establishment of a city. Many genealogical researches remain unconfirmed by uncertainties in family trees. In Rome we say “siamo tutti figli di Giulio Cesare!” (“we are all Giulio Cesar’s sons!”). An example for the Giustiniani making use of the hypothesis that they were instrumental in establishing in Rome; Genovesi, coming from Chios, in order to credit himself with the Papal court, was able to take advantage of the prestige that came from the ancient descendancy from Giustiniano the emperor (in Latin emperor “Giustiniani” o “Iustiniani”). Many historians....and all the Giustiniani…., wrote that Giustiniani come from the emperor Giustiniano, but this has yet to be proven conclusively.

2- The Giustiniani palace in Rome (by which the building is still known) is the seat of the Italian senate. In this building the Italian republic constitution of 1948 was signed. In effect the sitting of the Senate takes place in two buildings: “Palazzo Giustiniani” and “Palazzo Madama”.

The migration of Latin families from Chios to Costantinople and Smyrna

When the island of Chios was conquered by the Ottomans in 1566, many families moved to Constantinople and Smyrna. A new current of exchanges in trade and relations begin between the Latins from Chios and Genoa and those of Constantinople. From the study of the Chios’ parochial registries, now conserved in the island of Tinos, and a manuscript, dated between 1825 and 1830, of Giovanni Isidoro, Catholic vicarious of Chios, recounting the dispersion of the populace after of the Turkish repression of 1822, we found the names of some of the old Latin families still present in the island: de Portu, Ferando, d’Andria, Castelli, Corpi, Marcopoli, Guglielmi, Giustiniani, Palassurò, Giuducci (Giudici), Reggio, Roustan.

Curiously, until XIXth century, there wasn’t the issue of nationality as regards to the Latins of Chios under Ottoman government, because there wasn’t a particular capitulation signed after the 1566 takeover, as was made in Constantinople after 1453 between Mahomet II and the Genoese colony. We suppose that these Latins conserved the own nationality, as we have evidence that Latins from Chios, when they migrated to Smyrna, still at the beginning of the XIXth century, were considered with a foreign nationality that was often, as in the case of the Giustiniani, was the nationality form their “original” country, in particular they come from Genoa, therefore: Italian.

After the conquest of Constantinople in 1453, some Latin families had found shelter in the Greek islands (Chios, Tinos, Syra, Naxos, Santorini), and when order and calm returned to the city, decided to return to Constantinople. This return migration quickened after 1537, when these islands, one after the other, were conquered by the Turks.

According to the registries of deaths of Saint Maria Draperis R.C. church in Pera, an important parish of Constantinople, from 1800 to 1855, 33.09% of the deceased persons were immigrants from three islands (Tinos 17,48%; Syra 13,43%; Chios 2.18%). We notice that those already established in Constantinople represent only 9.92% of the deaths. The Latins were re-united under a civil and religious body called “Magnificent Community”. This Community, around 1840, was placed under the jurisdiction of the Turkish ministry of the Foreign nations, took the name of “Ottoman Latin chancery” and its activity continued until 1927.

Examining the registries of deaths held at Saint Maria Draperis church, we found in the period from 1800 to 1855, the following names represented Latin families that had emigrated from Chios to Costantinople: Braggiotti, Bragiotti, Carco, Caro, Castelli, Charo, Cochino, Coresi, Coressi, Corpi, Doria, Gaidani, Gallizi, Giro, Giustiniani, Isidoro, Jobini, Jobiori, Justiniani, Magnifico, Marcopoli, Marcopolo, Massoni, Nomico, Petier, Piperi, Renaccio, Tubini, Vegeti, Xenopoulo, Zoratelli.

The foreign Latin Community lived its golden age from 1839, emanating out of the reforms of modernization of the Ottoman Empire, until the abolition of the capitulations with the Peace treaty signed at Lausanne on 24 July 1923. The new Republic of Turkey did not delay in applying a certain number of measures to liberate its commerce from foreign domination and that exercised by the minorities.

The Giustiniani branch in the city of Smyrna, come from of the family Giustiniani-De’ Fornetti (Count Palatino arriving in 1413), decreed a marquis by the Italian Sovereign on 22 February 1893, (recognized as a noble and patrician of Genoa by the Sovereign on 20 June 1891), a family also present at the time in Chios, Genoa, Spain and Sicily.

The last descendent was Marquis Francisco-Brizio-Edmondo Giustiniani-De’ Fornetti born in Smyrna on 13 January 1840, son of Marquis Niccolò Giustiniani-De’ Fornetti born in Chios on 1798, died in Smyrna in 1872.

Francisco-Brizio-Edmondo Giustiniani-De’ Fornetti married Maria Giustiniani-De’ Fornetti born in Smyrna on 13 December 1842. They had nine sons: Maria (Smyrna in 1842, married to Emilio Levante I.R. Vice Consul of Austria-Hungary Empire in Alexandretta), Emilia (married Ernesto Guillois), Edmondo (Smyrna in 1869, married Maria Baroness Aliotti), Anna (Smyrna in 1870, became a nun), Laura (married to Pietro Filippucci), Giovanna, Niccolò (Smyrna in 1875), Margherita and Cristina.

The presence of the Giustiniani in Smyrna was confirmed from a list (1786) of non-Muslim merchants operating in Smyrna at the time.

Enrico Giustiniani (enrico.giustiniani[at]tiscali.it)

Note: There is further on the Chios link of the Giustiniani family in the book of Willy Sperco ‘Les Anciennes Familles Italiens de Turquie’.