This

veteran film buff and lover of the ‘Beyoğlu life’ has not kept

family records but his mother did. After her death, going through her

personal papers, an envelope labelled ‘documents’ came to light, and

they contained the following. A 1924 dated document issued by the Greek

consulate in Istanbul, written partly in Greek partly in Ottoman script,

with a photo of his 1860 born grand-mother Maria Anna Filipucci. However

he doesn’t know of its content as he cannot decipher these languages.

Another document, issued by the Spanish consulate in Istanbul in 1917,

details information on Mr Scognamillo maternal uncle, Jean Filipucci

(name in Greek version), who was a 20 year old student at the time.

It is interesting to note that during the time of WWI, neutral Spain

was responsible for the protection of the Greek residents of the city.

Death certificate issued by the Greek Baloukli hospital for his grandfather

George Filipucci in 1919. Grave plot purchase agreement in the Latin

Catholic cemetery of Feriköy, for his grandmother Paolina Scognamillo

in 1910. Black bordered death announcement of grandfather Gennaro Scognamillo

in 1910, including names of relations, most of which are unknown to

Mr Scognamillo, from Napoli and Izmir. A document issued by the Royal

Italian consulate given to his parents in 1936, inviting his parents

to the Italian club. From the paper it is clear that the invitation

was in response to his parents donating their golden wedding rings for

the upcoming victory (in Abyssinia) replaced by iron rings blessed by

Mussolini. His mother was not keen on this swap, but his father was

fascist leaning. Mr Scognamillo remembers attending the ceremony in

the crowded hall of Casa d’Italia as he was the junior member of the

party!

Mr Scognamillo was born in Şişli, Istanbul in 1929, the son

(only child) of Elisabetta Filipucci, and Leone Scognamillo. Mother

is an Istanbul born Greek whose roots are in the Aegean island of Tenos,

and father is again Istanbul born but origins from Naples. The first

7 years of his life were spent in Asmalımescit street in Beyoğlu,

a traditional built house that no longer stands.

Mr Scognamillo, by publishing this book and later interviews has allowed

the general puplic to have a better understanding of who the Levantines

are and celebrates his family’s heritage interwoven with his film and

Beyoğlu nostalgia, with this work. The book is full of vignettes

of a life much changed now, such as the last Greek carnival staged in

the district of Feriköy, to which he went with his father.

Note: The above passage is a summary taken

from chapter 1 of his book ‘Bir

Levantenin Beyoğlu anıları’ – [The Pera

memories of a Levantine], first published in 1991, and republished in

expanded form in 2002 by Bilge Karınca yayınları, Istanbul.

For extra insights, there follows a translation of an interview done

with Mr Scognamillo in 2003 by a university student, Volkan Ecer, previously

available on the web, in Turkish.

Can you tell the story behind you living in Istanbul?

My grandfather who was a chef, came to Istanbul from Naples mid 19th

century. His first job was as a labourer on the construction of Haydarpaşa

breakwater, and later was able to return to his profession. So I’m a

third generation immigrant.

Can you explain what is a Levantine?

A Levantine is a westerner who lives in the east. In the past there

were many Levantines living in Istanbul, Iskenderun and Izmir. The majority

were Italians, but there were also French, British and Germans, all

of whom shared the characteristic of living for a few generations in

Turkey. Currently the numbers are very low, and the new generation have

mostly preferred returning to their ancestral homelands. I have two

children, they both live abroad.

Have you ever thought of leaving Istanbul?

From time to time I felt the need to leave. But if a person spends his

life in a place, he becomes integrated there. The critical thing is

to achieve that integration. Some times I challenge other Levantines,

‘look I’m integrated, and you’re not’, they get offended of course.

I was a witness to the 6-7 September events when I was on Istiklal Street.

I was affected by the situation, but I never thought of leaving Istanbul

because of such events in Turkey, because they did not directly affect

me or other Levantines.

Why do you think Levantines coming from the developed west, chose to

live in the less favourable east?

Istanbul and the east have many attractions. This is not solely an impression

of my generation or generations before me. There are many young foreign

students who are struck by Istanbul. Istanbul still retains that attraction.

Because we live in Istanbul, with all its good and bad points, we might

ponder on how others are attracted to it. But they might have a different

perspective, such as the chaos of Istanbul as opposed to the order in

Europe, may be the source of this evocation. Europeans, in comparison

to the hustle and bustle here, have relatively monotonous lives, and

some compare this frantic Istanbul to New York.

Do you think a source of this attraction could be the mystic nature

of Istanbul?

Of course, could be, in some areas the old and the new go head to head.

For example, the tourists love Sultanahmet square. There you’re both

in a modern setting and yet history is all around you. Naturally this

is not unique to Istanbul, similar admixtures exist in Rome, Paris and

London. However Istanbul has the orientalist element, squeezed between

east and west, and that has an inherent attraction. A street I may pass

frequently, could be a different world to a visitor. Sometimes I think,

what would Istanbul be like without the Bosphorus.

If we went on a city tour with you, what would you consider to

be the most attractive area?

It could be Sultanahmet and surroundings as it encapsulates the history

of Istanbul. For natural beauty, the Bosphorus and Prince’s islands,

and because it’s my neighbourhood, Beyoglu.

What are the differences in Beyoğlu

between your youth and now? How do you reflect on nostalgia?

Not only Beyoğlu, all of Istanbul has changed. I’m not a nostalgic

person, the past is in the past, we need to live in the present. It’s

only natural for Beyoğlu to change, as it was too much of a special

place. Particularly during the Ottoman times, the neighbourhood was

a historical contradiction within Istanbul. Like a piece of Europe broken

away and inserted. If you look at the impressions of 18th

and 19th century western writers, they don’t consider Beyoğlu

to be western. But within Istanbul the quarter was a different world.

The artists and intellectuals of Istanbul were always drawn to Beyoğlu,

as it provided a range of outlets not found elsewhere in the city. During

the 18th and 19th century all things western would

enter Istanbul through Beyoğlu. But the social foundation of Beyoğlu,

the minorities and Levantines are now disappearing. Various political

and economic factors has caused emigration, such as the foundation of

the state of Israel. All these have had a negative impact on Beyoğlu

and Istanbul.

Are there any of the minority shop keepers left in Beyoğlu?

None left. In the past virtually all traders in clothing or entertainment

establishments, belonged to minorities. For example, when someone said

a pub [meyhane], it meant a Greek pub.

Could Beyoğlu be considered the spoilt child of Istanbul’s

culture and art centres?

Beyoğlu has more entertainment centres than elsewhere in Istanbul,

so this depiction is correct.

Could you talk a bit about your book, ‘the mysteries of Istanbul’?

To be frank, that book is still a nuisance to me. I rewrote the book

in Italian and it was published in Italy. I have a strange nature, once

I have finished a book, that book for me is then dead. I don’t read

my books once they have been published, the important thing is the next

book.

What do you think for the future of Istanbul?

That’s a wide subject as it is linked to the future of Turkey. Unfortunately

because Istanbul has grown in a disorganised way, rearranging it would

be very difficult. There are still many problems and I have no solutions.

Considering the other fine cities of the world such as Prague, Paris

and London, where do you think Istanbul would fit?

It’s as important as those cities. There is a culture founded by Byzantines,

linking Romans, Greeks, a whole world. Added to this are the Ottomans

and even Jews from Spain. For this it is difficult to research history

in Turkey as we don’t reach the sources, as we live within them. The

Ottoman archives are not studied sufficiently. For example on the subject

of Beyoğlu and Levantines, only last year I came across four foreign

researchers, some doing PhD thesis. I don’t know if there are any locals

who have done work on this subject. One Levantine academic did work

on the Levantine past of Pangaltı, which was published by the Şişli

council. I find it strange that all this is done by outsiders; these

should have been done by our people living in Istanbul.

Considering the social life, how were the relations between Levantines,

minorities and Turks?

There was never animosity between the communities. The evil every time

is religious or political intolerance. For example if it were not for

the Cyprus events, most of the Greeks of Istanbul would not have emigrated.

Societies always find communality for harmony. When I was a child Moslems

would participate in Easter and Christmas celebrations. Likewise minorities

and foreigners would join in Ramadan and Kurban [sacrifice] feasts.

It’s the politicians who have ruined the atmosphere of tolerance and

peace.

Our elders tell us that in the past everybody would be attired in

tie and starched collars in Beyoğlu, is this true?

We need to also consider the factor of fashion. Until the end of WWII,

normal dress was a suit. I remember when I was at high school, there

was a famous clothing store by the name of Mayer. One day wandering

with my friend, I saw some casual trousers, liked and bought them. But

late we thought we couldn’t wear these in Beyoğlu. In those days,

casual trousers were considered outlandish, but of course now everybody

has chosen to wear comfortable articles.

Have you ever thought of living in any city apart from Istanbul?

I considered it for a while, then gave it up. While I was working in

London, I considered settling there, but nostalgia for Istanbul won

out. With my age [74] I cannot leave the city now.

How many Levantines are left in Istanbul today, can you give numbers?

They have dwindled significantly. As Italians a thousand at the most,

in the 1950s this number was around 6,000. I do not count foreign visitors

here for work in these.

Finally can you give an anecdote relating to the history of Istanbul?

A popular one goes, when Fatih [The Sultan Mehmet II, the conqueror

who took the city in 1453] just after his victory entered the Hagia

Sophia, there was a service going on. Of course, when the Ottomans entered,

there was pandemonium. The priests conducting the service enter a wall

and disappear. According to the legend, when the city is recaptured

by the Byzantines, they will re-emerge from the wall to resume the service.

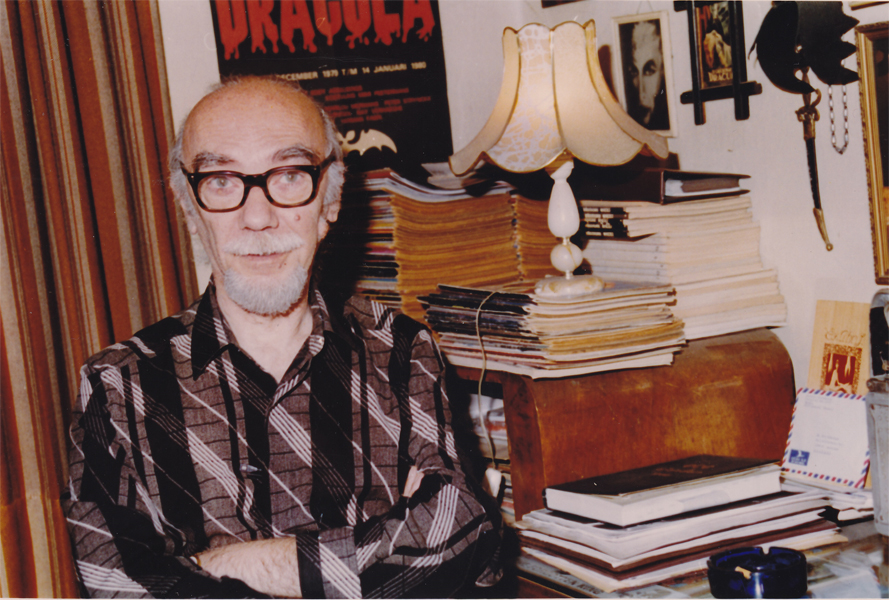

The 3 ages of Giovanni Scognamillo

Notes: 1- Mr. Scognamillo has written

an impressive number of books, all in Turkish, on the subject of Turkish

cinema history (first one published 1974) as well as the history of

his neighbourhood of Beyoğlu. Soon (2005) his latest, ‘Beyoğlu

Writings’, is going to appear in Turkish, a collection, once again,

of writings on Beyoğlu. Also recently (June 2005), a student of

communications at Marmara University, Ebubekir Çetinkaya, has

undertaken to create a documentary

film on the life of Giovanni and the neighbourhood with which he

is often associated, Beyoğlu. He has also starred in a number of minor roles in Turkish movies:

Online articles: Istanbul’s last Levantine misses the old Beyoğlu:

Through the eyes of a Levantine Pera - Rıza Kıraç

2- Text of an interview of Giovanni by Alberto Tetta, 2010.

3- View Giovanni’s sitting room / study arranged in a Flash panaroma programme with clickable information:

4- Unfortunately Mr Scognamillo died after an illness on 8th October 2016, may he rest in peace - obituary:

|

![]()