The

following article is a compilation of Mr Mango’s direct contribution indicated

through speech marks and my addition from a translation of his article

published in a Turkish newspaper in March 2001, interviewed during a visit

to Istanbul. I also made minor use of the article ‘The Brother’s Mango’

published in 1999 in issue 19 of Cornucopia.

‘My great-grandfather’s father was “Capetan” Andoni Mango. The nickname

suggests he was a sailor - not an unusual occupation in Chios. We know

nothing of his ancestors. Nor do we know when they came to Chios. Mango

(supposedly meaning little merchant) is not an unusual name in Italy:

there’s a commune in Sicily (next to the ruins of Segesta) called Mango.

A village in Piedmont also bears the name. The reason why the family assumed

that they were of Genoese origin was that Chios was a Genoese possession

from 1261 to 1415. But a successful Italian painter, Leonardo

de Mango, who was active in Istanbul between 1883 and 1930, was not

Genoese. Incidentally, Livio

de Missir, an expert on the Levantines, who was in charge of the Turkish

desk at the EU in Brussels, told me that he could find no trace of Mangos

in the list of gentry (the so-called Gold Book) in Chios.

My great-grandfather, Dimitri, left Chios

at the time of the Greek uprising (1821) and sought refuge on the island

of Syra

in the Cyclades, where he was registered as a Greek subject after Greek

independence in 1830. He moved to Istanbul in the early 1840’s, as the

Ottoman empire began to prosper under the Tanzimat reforms, while Greece

was free, but hungry. He was part of a considerable migration from the

islands to Ottoman Turkey. He became a printer to the Catholic church,

married a Catholic, a Carolina Calavassi, from the island of Syra in the

Dominican church

of St Pierre and St Paul near Galata tower. The church, where my grandfather

was also christened, served a congregation of Catholics from the islands

and, particularly, from Malta, who were employed in the harbour. The church

registers in Latin, still bears this history out. According to Missir,

the Calavassis were “a good family” on the island. I don’t know how many

children she had. I think I saw four mentioned in the baptismal records

of the church in Galata. I’ve no idea what became of them. But clearly

none, apart from my grandfather, made a mark.

My grandfather, Anthony, made a fortune in the 1880s-90s establishing

coaling stations from Hamburg to the Black Sea, and then formed the Foscolo

Mango Steamship Co. [archive letter-head], his partner Foscolo coming from a Venetian family

on the island of Corfu (which produced the well-known Italian poet Ugo

Foscolo). The company was probably formed in the last decade of the

19th century, as grandfather died 1904-6 period. I can remember the cutlery

at home with the initials F.M.S.Co. and a little flag. The coaling stations enterprise was a huge venture, done on his own stretching from Hamburg, right through to Odessa with stations around the Mediterranean, such as Pireaus, Istanbul, Novorosisk. My grandfather

married a Greek called Evangeline Margaritis. Her family had come from

Epirus, and was probably of Albanian or Vlach

origin. My guess she came from a lower middle-class family, compared with my grandfather’s family. The family story is grandfather saw her once in an upper window of a house, declaring he will marry her, however it is probably a legend. They had 5 children, Anthony died in Karlsbad in 1906, quite young in his 50s, hopelessly trying to cure his diabetes, in the days before knowledge of insulin. Through the coal and latter shipping business he became a very rich man. He lived mainly in Istanbul, near Galatasaray district, Pera, which at the time had large mansions but today is a run-down area. The actual house is still standing. Family fortunes crashed with the depression, as the shipping business was one of high outlay and idle ships would quickly become a major liability.

As the coal came from South Wales and the Durham coalfields, my grandfather

set up an office in London and sent his eldest son, John, to manage it.

Uncle John married Marie Karatheodori, the daughter of Karatheodori [Turkish

spelling: Karatodori] Pasha, who was the Ottoman foreign minister at the congress in Berlin 1878 and the then Ottoman ambassador in St. Petersburgh. (Their son, so my cousin,

was killed, serving with the RAF during WWII, was called Anthony,

a name he shared with another cousin of mine, who was killed in the ranks

of the Greek army in Albania in 1940). Karatheodori Pasha was simultaneously the vassal Prince of Samos, because after the Greek revolution, the Great Powers didn’t want to give it to Greece or return to the Ottoman Empire because of the Greek community, so it became a self-governing mini principality. He may have visited the island though he never lived there.

My father, Alexander, was sent in around 1900

to England to study first at the Lees School, a Methodist public school. Yet grandfather was born in Catholic, but when he married his wife became a Greek Orthodox, but was also a prominent Freemason, and Catholics weren’t allowed in that institution, yet masonic connection worked really for business in England. Father then studied law at Cambridge and then read for the bar. He was

naturalised a British subject in 1902. He returned to Istanbul to practise

at the British consular court and work

nominally as a director of Foscolo Mango. The

British Consular Court tried civil law cases involving British subjects

and (possibly) other foreign nationals. However, under the Allied occupation

(1918-1922) it dealt also with police cases. I have a feeling that it

sat somewhere in Galata, but I am not sure.

Under the Allied occupation, 1918-1922, the family firm joined other shipping

agents in what was in effect a cartel called Marine Manutention. The word

“Manutention”, is a bit of a mystery, but I suppose, implies maintaining

ship’s agents’ services or hanging on to passing ships to make sure that

no other ship’s agents serviced them!

However following this period Istanbul was in steep decline as trade with

Russia had been cut off and the new nationalistic regime in Turkey was

steadily constricting traditional business activities. Foscolo Mango went

down in the great depression of 1929.

I was born in a house in Beyoğlu, Istanbul near the British Consulate

and went to the English High School for boys. Some of the boys were sons

of German Jewish refugee academics teaching in Turkey - Frank, Neumark,

Schacht, etc. There was also a strong - and rough - contingent of Maltese

boys whose fathers were tradesmen in the harbour. The headmaster was Charles

Peach (unfortunately, ‘piç’ is Turkish for bastard); one

of the masters was Tony Alderson who went on to compile the Oxford Turkish-English

dictionary (with Fahir İz); another master, Ian Campbell, ended up as

dean at a Methodist college in Nebraska, etc. I matriculated in 1942 aged

16 and worked for a couple of years in the Balkan Press Reading Bureau

at the British Consulate in Istanbul, translating from newspapers published

in Bulgarian and Croatian under the German occupation. (My mother Ada

was a White Russian refugee and I found it easy to learn other Slav languages).’

|

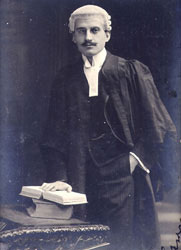

Grandfather Anthony Mango taken in Newcastle. |

My paternal grand-mother Evangeline née Margariti. |

Father aged around 7, early 1890s. |

Father, Alexander Mango, taken in London, about 1910. |

I don’t know how my parents met, but clearly my dad was a good catch for a refugee from Russia. Ada lost both parents in the turmoil following the Bolshevik revolution

and the civil war in Russia, and escaped alone by train and foot, like

many others to land destitute in the streets of Istanbul. My mother’s

maiden name was Damonov. She did not come from the aristocracy, but was

middle-class. The marriage was unpopular with my grandmother as she clearly had no dowry. The couple communicated in French, as my father’s French was excellent and in those days the Russian bourgeoisie also spoke French. She came from Baku where her father was an oil engineer in the original Nobel concession - the first oilfield exploited in Baku and virtually the world’s first large scale exploitation. Her parents died fairly young, but of natural causes, during the period of the Russian revolutionary turmoil. Her father came from governate of Tambov which is in South-Central Russia, the so called black earth belt, where his father was a grain merchant. Russia was a major exporter of wheat in those days and much of the wheat passed through Istanbul. My mother died in England in 1987 (aged prob. 93).

Mr Mango is clearly a linguist as he already knew French, Latin, Greek.

His Latin however was rudimentary as it was taught at the English High

School on a voluntary basis after hours, as the timetable had no other

gaps, because of compulsory Turkish (which was very badly taught), history

in Turkish (in addition to history in English), etc.

|

The British Consular court in session in the British Embassy, with my father present. |

My Russian mother Ada (Adeleide) née Damonov. |

Me aged around 4 and my brother Cyril on the right at our summer house on Büyükada. |

Mr Mango has fond boyhood memories of summers spent on the Prince’s island

of Büyükada (Prinkipo), where his brother, Cyril’s passion (now

an expert) for Byzantine history was fired by the remains of walls of

Queen Irene’s monastery, where she was imprisoned during the 8th century. I remember seeing the ruins from the Büyükada ferry half a century ago the Victorian folly of a former British Ambassador, ‘Bulwer’s castle’ on Yassı Ada which stands no more.

Unlike many British subjects the Mangos did not move to the relative safety

of Iskenderun, as the German armies neared the Turkish borders in World

War Two. He remember the sound of anti-aircraft batteries opening up on

Allied planes off course and flying over Istanbul on their return of bombing

raids over the strategically vital Rumanian Ploesti oil fields. For patriotic

reasons there was a boycott of shops known as ‘German’ including the still

existing ‘Sutte’, except for when the craving for ham became too big.

Note: This ties in with Mary Lemma’s

testimony of the German Sutte who as a tennant ran a pig farm on the family

estate in Zincirlikuyu.

The war years were a period of stress to all minority communities who

were targeted for an extortionate ‘wealth tax’, whose epicentre was amongst

the merchants of Beyoglu. The Levantines seem to have been spared the

extremes of the abuse by the tax assessors and collectors. ‘I remember

the British Consulate discussing with my father his assessment for Varlık

Vergisi, and finally advising him to pay a much reduced sum. Your

information, therefore, sounds right.

I left Istanbul in 1944, going first to Ankara where I worked as a translator

(English to French - French was spoken at home) at the British Embassy

press office. My boss in Ankara in 1945-7, was an Izmirli, Roy Tristram

who had the title of Radio Attache (he was in fact the assistant Press

Attache). Roy was a Catholic and I met him once outside the Brompton Oratory

in London in the late 1950s. He was an amusing man, spoke good Turkish

(and Greek) and was on good terms with the Turkish journalist community

in Ankara. Our main job was to feed British-source news to the Anatolian

Agency, which had a monopoly of news distribution and accepted news from

foreign embassies in French only - hence my job as English to French translator.

I accepted a job offer from the BBC while in Ankara as I was looking out

for a job that would allow me to enrol in a university in Britain. I came

to England early in 1947 (the Dakota stopping off in Athens, Rome and

Marseille) to work for the BBC external broadcasts (now the World Service),

and, at the same time, study at the School of Oriental Studies, London

University, where I read classical (mediaeval) Persian and Arabic. I became

assistant head of the BBC Turkish Section in 1957, head three or four

years earlier, and was in charge of Turkish language broadcasts for fourteen

years to 1975 or thereabouts before being promoted head of all the South

European and then also of the French language services. I had to learn

a fair amount of Italian and Spanish as head of the BBC South European

Service. I retired from the BBC in 1986.

Note: In celebration of the 62nd

anniversary of Turkish language broadcasts from the BBC, the web

site gives an insight to the diligent ways Mr Mango worked as head

of Turkish section between 1958-1972. ‘It was the summer of 1960. In my

second year of head of Turkish broadcasts by the BBC I was in Ankara,

staying at the former Ankara Palas hotel. Facing it in the former parliament

building the newly appointed ‘National Unity Committee’ [MBK] is meeting.

When I met up with the youngest member of the MBK, his first words were,

‘I congratulate you, pre 27th of May, you gave the most accurate news.

How did you achieve this?’ I said, ‘Easy, British journalists were sending

news from Turkey, the only issue was to check on their accuracy and broadcast

them independently of political influences’. In reality it wasn’t so easy,

the rules of the BBC were firm; such as the news had to be verified by

a second independent source, limiting news synopsis to headlines rather

than reports. We worked hard to ensure these rules did not prevent the

broadcasting of the news we knew to be right. In a way we were the pioneers,

and as a result the then forming TRT (Turkish state broadcasting) embraced

the principles of the BBC and the initial contingent were trained by the

BBC. Of course later, everybody went their own way.

I certainly remember Baker’s establishment in Istiklal Caddesi. I did

not know the owners, but one of my friends at school, Henri Ergas (who

later became a departmental director at the UN FAO headquarters in Rome

and then at Banque Rotschild), was the son of a manager, who advised Ataturk

when the merinos woollens factory was set up in Bursa. The other names

are also familiar to me, although I did not know them personally. Schembri

was, I think, of Maltese origin and worked in shipping.

I did not, of course, attend the Crimean Memorial Church, but remember

going there with the school for special services.

As far as places of burials go, they vary with the generations. I assume

that my great grandfather was buried in the Latin cemetery at Feriköy,

but I haven’t checked. My grandfather became nominally Greek Orthodox

when he married (and became a freemason!). He was buried in the Greek

monastery of St. Nicholas on the island of Büyükada (Prinkipo)

where the family had a summer house. My father was buried in the Greek

cemetery at Şişli.’

The Mangos went to church only twice a year to the small Russian Orthodox

church in Galata, that still survives with a relict congregation.

Note: St

Andrei is still functioning as the church of Istanbul’s white Russians,

a relict of 19th century pilgrims’ stopover, one of 4 churches within

a stone throw of each other. These ‘roof-top’ churches are covered in

detail in an article of issue 28 of the magazine ‘Cornucopia’ (Feb 2003).

The reference to Karatheodory Pasha clearly shows at the time the Ottoman

court did not discriminate against Christians who were able to rise to

such high ranks and Alexandros Karatheodory [İskender Paşa]

clearly was loyal and was responsible for rooting out nationalistic elements

in Crete in 1896, the time when the final Greek insurgency began, when

he happened to be the governor of Crete (second term: 1895-6).

Notes: 1- Amongst the books of Mr

Mango are ‘Turkey (New nations and peoples)’ (Thames & Hudson - 1968), ‘Discovering

Turkey’ (Batsford - 1972) ,‘Turkey, a delicately poised ally (The

Washington papers)’ (Sage - 1975), ‘Turkey: a challenge of a new role’

(Praeger -1994), ‘Ataturk:

the biography of the founder of modern Turkey’ (John Murray, London / the Overlook Press, New York

– 2000) which has received high praise and was followed by ‘The

Turks today’ (John Murray, London / the Overlook Press, New York - 2004). Mr Mango’s more recently published books are (Nov.

2005), ‘Turkey and the war on terror: For thirty years we fought alone’ (Routledge - 2005),

has also received favourable reviews, and his latest (Haus Publishing, July 2009) is ‘From the Sultan to Ataturk: Turkey - The peace conferences of 1919-23 and their aftermath’.

External interview: Research Turkey (August, 2012), ‘Interview with Dr. Andrew Mango: Turkey’s Walk from 1923 to 2023: A Critique of Past and Recent Political Challenges’.

2- Unfortunately Mr Mango died on 6th July 2014, peacefully in his sleep. May he rest in peace.

interview date 2003-10

interview date 2003-10

|

![]() interview date 2003-10

interview date 2003-10