Rose Marie Caporal | Alessandro Pannuti | Ft Joe Buttigieg | Mary Lemma | Antoine ‘Toto’ Karakulak | Willie Buttigieg | Erika Lochner Hess | Maria Innes Filipuci | Catherine Filipuci | Harry Charnaud | Alfred A. Simes | Padre Stefano Negro | Giuseppe Herve Arcas | Filipu Faruggia | Mete Göktuğ | Graham Lee | Valerie Neild | Yolande Whittall | Robert Wilson | Osman Streater | Edward de Jongh | Daphne Manussis | Cynthia Hill | Chris Seaton | Andrew Mango | Robert C. Baker | Duncan Wallace QC | Dr Redvers ‘Red’ Cecil Warren | Nikolaos Karavias | Marianne Barker | Ümit Eser | Helen Lawrence | Alison Tubini Miner | Katherine Creon | Giovanni Scognamillo | Hakkı Sabancalı | Joyce Cully | Jeffrey Tucker | Yusuf Osman | Willem Daniels | Wendy Hilda James | Charles Blyth Holton | Andrew Malleson | Alex Baltazzi | Lorin Washburn | Tom Rees | Charlie Sarell | Müsemma Sabancıoğlu | Marie Anne Marandet | Hümeyra Birol Akkurt | Alain Giraud | Rev. Francis ‘Patrick’ Ashe | Fabio Tito | Pelin Böke | Antonio Cambi | Enrico Giustiniani | Chas Hill | Arthur ‘Mike’ Waring Roberts III | Angela Fry | Nadia Giraud | Roland Richichi | Joseph Murat | George Poulimenos | Bayne MacDougall | Mercia Mason-Fudim née Arcas | Eda Kaçar Özmutaf | Quentin Compton-Bishop | Elizabeth Knight | Charles F. Wilkinson | Antony Wynn | Anna Laysa Di Lernia | Pierino & Iolanda Braggiotti | Philip Mansel | Bernard d’Andria | Achilleas Chatziconstantinou | Enrichetta Micaleff | Enrico Aliotti Snr. | Patrick Grigsby | Anna Maria and Rinaldo Russo | Mehmet Yüce | Wallis Kidd | Jean-Pierre Giraud | Osman Öndeş | Jean François d’Andria | Betty McKernan | Frederick de Cramer | Emilio Levante | Jeanne Glennon LeComte | Jane Spooner | Richard Seivers | Frances Clegg

|

The

Streaters went out from two villages in Sussex (Worth, West

Hoathly) to Constantinople in 1864. The family are allegedly descended

from a famous painter in his time (end of 17th, beginning of

18th century), Robert Streater, portrait painter during the

reign of Charles II. The Streaters were farmers and millers and in the 1860s, farming

in England was in a terrible state, and that is when also another branch

of the family emigrated to Australia and New Zealand. Recently I made

contact with those Streaters, and ‘Aha’ said a cousin in New Zealand,

‘we have found the long lost Constantinople branch’. I don’t know why

my great-grandfather chose to go to Turkey, rather than the classic emigration

destinations. However the farming crisis may have been a secondary factor,

as according to cousin Diane Streater, the emigrant Streater described

himself as a “Draper’s Clerk”.

My father and grandfather was both named Jasper, and the tradition goes

back as far as I know to the 18th century, so I am the first

in a long line to break the custom. I use my Turkish name by choice and

was given it by tradition by my Turkish mother’s father, Muvaffak Menemencioğlu,

possibly to signify the family’s link back to the first Ottomans in Anatolia.

From the Istanbul British consular registers I know great-grandfather

came to Turkey in 1864 aged 21, but do not know if he came as a bachelor

or married, what he did, or when and where he died. Why did my lot go to Istanbul? I have no answer, I have virtually no written evidence from this side of the family. According to family folklore they did build a mill, but the Armenian rivals soon burnt it down, and so they settled down to a more modest life of working for companies.

Grandfather

Jasper worked as a clerk for the Blair and Campbell shipping company [archive letter covers] and

also as a British vice-consul based in Rodosto [modern Tekirdağ - info - archive views]

on the northern coast of Marmara Sea [approximately half way between Constantinople

and the Dardanelles], and there is a high likelihood he was a shipping

agent based in this minor port. He married in 1900 and had 5 children.

I never got to know either my grandfather or his wife as they died in

1936 and end of WWII respectively (I was born in 1942). The Rodosto residence

must have been sort of a summerhouse, as it is mentioned as a house by

the newspaper / war correspondents [example in a book] who stayed there, covering the Balkan

war of 1912-1913 [archive views]. The family left the place just in time (my father

as a 5 months baby) before the Bulgarians occupied the place, in their

successful push right to the gates of Constantinople (to San Stefano –

Yeşilköy). Then it was reported in Constantinople that, in the military hospital for Turkish wounded soldiers, cholera had broken out. Ottoman women didn’t do nursing in those days, so the wounded were untended. So two of grandfather’s sisters (one named Lee) said to each other: “Come on, girls, we can do this.” And they went out to nurse the cholera-ridden Turks.

The first sign of Turkish gratitude came with the entry of the Ottoman Empire into the First World War, when all Brits were ordered to leave. The Streaters were told that, because of what their womenfolk had done for wounded Turks, they could stay, as opposed to all French and British citizens in Constantinople, who are ordered out. However the family nevertheless did leave for England

for the duration of the war and when it was over, they went straight back.

Note: Newspapers of the time have some

illustrations of English volunteer

nurses, possibly in the same capacity the Streater sisters worked during

the Second Balkan War.

My father, born 1912, goes to the British run Istanbul high school for

boys, as does his elder brother Roland who at a young age moves to Kenya

and later South Africa, where his descendants continue to live. Father

had 3 sisters (the eldest named Joyce), 2 of which (Sybil and Isabel)

worked as secretaries for the embassy, that later became the consulate

(the transition was not contemporaneous with the establishment of the

republic in 1923, as first the building had to be built and at first was

totally unpopular with the ambassadors who were used to the comforts of

Istanbul). Isabel noticed an advertisement by an Agabekov, a Russian who

wanted to learn English in 1929. A relationship quickly developed and

they fell madly in love with each other. When her father found out, he

was horrified (after all he was a ‘foreigner’), and literally locked her

up in his house. The family at this stage were hard working and desperate

to improve their social status, and this would have rocked the boat. Agabeyov,

was in fact the local head of the NKVD (pre-runner to the KGB), a spy

in Istanbul, and clearly his love was genuine as he went to the British

consul and offered a deal, whereby if he could marry his girl, he would

defect and give away all his secrets. Two officials from London came,

and explained the situation to a shocked father, and told him it was his

patriotic duty to give his daughter. He did however agree and the couple

married and started a life in Brussels, Belgium. The shadowy Russian counter-espionage

organisation Smersh

[or rather its precursor - the name is a Russian acronomy for ‘death

to spies’], traced Agabekov

and assassinated him in his hideaway at the end of the 1930s. The widow,

was still popularly remembered by the foreign office and started working

as a secretary again for the British ambassador, Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessan,

and carried on working till she died aged 60, by which time she was working

as a secretary to the British ambassador to the United Nations, based

in New York.

Notes: Mr Streater is sure Agabekov

was given a new identity in Brussels, but don’t know what it was. Such

as he knows of him comes from the two chapters about him and Isabel in

Gordon Brook-Shepherd’s ‘The Storm Petrels: the first Soviet Defectors

1928-1938’, published 1977.

In addition Mr George Agabekov wrote a book in 1931 on his experiences with the OGPU, ‘spilling the beans’ on that murky world, no doubt making him further a ‘marked man’ in the Kremlin circles - segment viewable here:

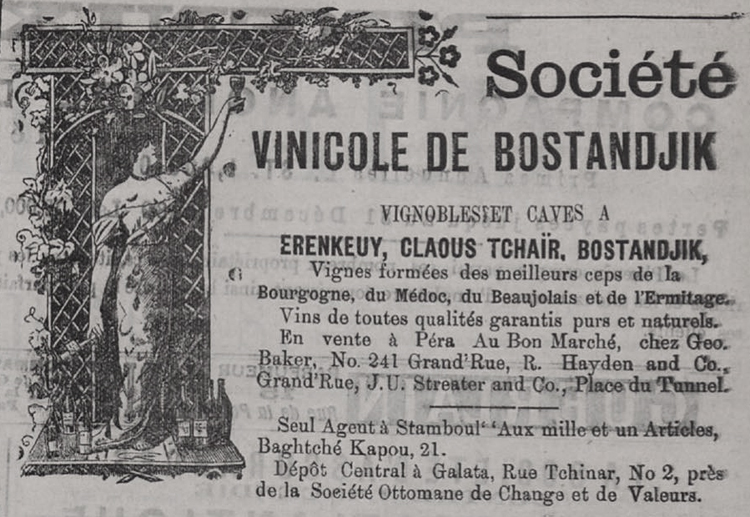

My father having finished the English High School, joined G&A Baker

in the 1930s, a firm based in Istanbul owned by the United Africa Company,

who were themselves owned by Unilever. There was a shop on the high street

of Pera in operation at the time, carrying the name G&A

Baker, but the company was a far grander thing, which had little or

nothing to do with the shop, and represented companies like the aviation

firm De Havilland and Marconi in Turkey and sought to win industrial contracts

and set up the first margarine factory in Turkey, soap powder etc. Post

WWII the firm had a branch in Ankara and from 1945/6 until closure, father

was Managing Director of the Ankara office. This was set up for, and specialised

in, dealing with government orders, e.g. for aircraft, so it had a different

focus as well as a different location to the Istanbul office. The Istanbul

office was for many years run by Peter Riddell, who had a villa in Yeniköy,

and whose grave is next to my father’s at Feriköy. At the end, there

was an eccentric MD of the Istanbul office sent out from London named

Peter Gregor McGregor, who always insisted on being called “Mr Gregor

McGregor”, and who would send his stiff collars to England to be laundered

and starched – he wore heavy Savile Row clothing all the year round. Istanbul

was undoubtedly in official charge of Ankara, and for example I remember

Gregor McGregor ticking off my father for allowing me to drive his company

black Rover, the only one of its kind in Turkey. On the other hand, Gregor

McGregor had no understanding of the Turks, while my father was Honorary

Secretary of the Ankara Golf Club, at the time the main social institution

in Ankara, even though described by Life magazine as “the worst golf course

in the world”. I remember my housemaster’s son, who we invited over to

stay when he was doing his National Service in Cyprus, writing in awed

tones to his father that they played bridge “simultaneously in English,

French and Turkish” at the Golf Club.

Father met my mother just before WWII

and with the outbreak of the war, volunteered and went straight to Middle

East and was trained at the staff college in Haifa. He was very successful,

rising through the ranks like a rocket, he was the Ultra contact at HQ in North Africa, and also becoming in a few years, a wing

commander, head of RAF command in Italy and acting air-vice marshal. He

was transferred from RAF intelligence to USAF intelligence for 6 months,

and provided information support to the successful raid

by the 165 Liberators, USAF bombers that on 1st of August 1943, caused

serious damage to the Ploesti oil field installations in Romania, the

chief source of oil for the German war machine. The American bombers had

the range for a return trip to Egypt, and they were selected as Turkish

authorities refused the RAF refuelling rights, but gave the Americans

fly-over rights. The Germans by this stage had cracked the American code

and this caused some losses, the crew of aircraft bailing out over Turkey

being interred by the authorities. For his assistance father was presented

with the highest decoration a non-US citizen could get (US Legion of Merit,

Degree of Officer) and I still have the certificate

framed, signed by the US president and commander-in-chief of the armed

forces Franklin

D. Roosevelt and Henry L. Stimson, Secretary of War. The official

US Army Air Force (it was only post war it graduated to a separate service)

volume of this raid makes no reference to this British assistance, and

recently Osman produced the certificate to convince a skeptical American

expert on the raid.

When my father Jasper Streater proposed marriage to my mother to be Nermin Menemencioğlu in 1941, the permission of the President of the Republic was required for a Turkish woman to marry a ‘foreigner’ - even one born second generation in that country - (imagine, what a contrast to today). So they applied via family links (Great Uncle Numan Menemencioğlu was Foreign Minister) to President İsmet İnönü. The President said that the Streater voluntary nurses had saved several of his military colleagues’ lives in 1912-13, and it was with the greatest of pleasure that he gave his permission for their marriage.

Father married my mother in 1941 in Cairo, but since he was not allowed

to go to a neutral country due to being involved in intelligence, it was

my mother who had to take several trips during the war for meetings during

his leaves, taking the RAF DC3 Dakotas that flew once a week from Turkey

to Egypt.

Father dealt with the top reaches of Turkish military then and after the

war, and though the authorities respected him, they suspected him of espionage,

phoning and asking for him when out of town, such as the Abant lake side

hotel, used as a stop over point in journeys between Istanbul and Ankara.

Father also dabbled in history and his main literary piece was an article

published in a historal magazine (History Today, April 1967), concerning

the profound effects of the battle of Manzikert in 1071, when “Anatolia,

heartland of Byzantium... was lost forever to Christendom” (Streater p.

257).

Returning to his work in Ankara, in the late 1940s and 1950s, the city

was still small and sociable, and together with his wife, Nermin (née

Menemencioğlu), hosted an endless round of cocktail parties, with

food and drink expenses born by him. These parties of 30-40 people, attracted

not just the expatriates, but artists and writers, some still struggling,

and for some it would be their only full meal for the week. The artists

represented a who’s who of the Turkish arts scene of the day, including

Abidin

Dino, Hasan Kaptan, Turgut Zaim, Salih Urallı, İhsan Cemal Karaburçak, Bedri

Rahmi Eyüboğlu, most of whom as a token of friendship donated

a piece or two to my father, so now I have a collection of over 20 works.

Some of these painters signed their works with their full name, Turgut

Zaim, Hasan Kaptan, some with the forename as an initial, B. Rahmi, while

most signed merely with their surname, Urallı, Karaburçak,

and one signed with his first name, Abidin. As for the writers of the

time, the regulars included Mahmut

Makal, Fahir Bayburt and I hold signed books of theirs, as well as

others.

My mother was (died 1994) an intellectual, going to Robert

College in Istanbul, spoke fluent French and English, the latter being

the language spoken at home. I have a photo

of my mother with the British ambassador during the war years, as she

acted as his interpreter. In the late 1930s and during the Second World

War, her father Muvaffak Menemencioğlu was Director General of the

Anatolian News Agency in Ankara, at the time the only news agency in Turkey

and of course the official one (and the probable source of the various

news photographs in my hand). Also, at that time, it was still unusual

for Turks to speak English. So I rather think that my mother’s services

were offered as and where required. She certainly also worked for the

US Embassy. I doubt that we can say that she was the British Embassy’s

official translator. My mother has also translated (in collaboration with

Fair İz in the 1960s and 70s) many of the works of the famous Turkish

poet Namık

Kemal, who also is her great-grandfather. Penguin published a limited

edition of this book back in 1978, which sold reasonably well, however

the present publishing climate seems to shun dead translators, so my efforts

of a republication have been unsuccessful. Namık Kemal’s great-great-great-great

grandfather was Sultan

Ahmet III. By coincidence Namık Kemal was born in Rodosto/Tekirdağ,

and later buried there; his body being transported there from Chios, where

he died as Governor. Another of my mother’s friends was Nazım

Hikmet, considered by most as the national poet, was a communist and

never apologised, so he spent considerable amount of time in prison, and

even today the authorities don’t seem to want to pardon him, so his grave

remains in Moscow. I saw him only once as a boy, I think it was 1950,

the year of his release and flight from Turkey to the USSR. It was in

a friend’s garden in Bostancı [a suburb of Istanbul on the Anatolian

side], I fell into the pool, he pulled me out. Within a week, he

had quietly boarded a passing Soviet steamer to Odessa by arrangement,

and was gone for eternal exile. Interestingly, as a non-royal family,

the Menemencioğlus are almost unique in Turkey in that they can trace

their past to 1218 in Anatolia.

Notes: 1- Mr Streater has recently penned an article on the life and archivements of Namık Kemal and has kindly allowed for its use in this web site, viewable here:

2- The book tracing this story

through archive records is ‘Menemencioğlu tarihi – Menemencioğlu

Ahmet Bey, Dr Yılmaz Kurt, Akçay basın, Ankara 1997’.

The detailed book chronicles the migrations of the family over centuries,

from Eastern Turkey to Menemen in the west, and when pressure by the authorities

in 1581 gets too oppressive, these 15-20 households migrate back to the

sparsely populated hinterland to re-establish their de-facto ‘derebeylik’

[clan fiefdom] north of Adana.

Drawing on this source and family archives Mr Streater has recently penned an article on this heritage and has generously allowed for its use on this platform, viewable here:

3- Also in 2007 Mr Streater has kindly submitted an article on the story of his maiden aunt, Isabel Streater whose story is recorded here:

My mother’s father Muvaffak’s younger brother was Numan

Menemencioğlu, who was permanent under secretary in the 1930s

and during WWII, as foreign minister, steered a course of strict neutrality

for Turkey. He had seen the results of the catastrophic mistake Young

Turks had done by joining the Central powers in WWI, and was determined

not to place his relatively weak country in another uncertain gamble.

However by 1944 the tide of war was clear, and the allies gave an ultimatum

to Turkey to join on their side if they wanted to join the UN, which they

duly did. Again under allied pressure, Numan Menemencioğlu was replaced,

and he was sent as ambassador to the newly liberated Paris, a good choice

of a candidate as De Gaulle knew and respected him. Since the old embassy

building was now occupied, De Gaulle told him to find a free place of

his own, and a grand building, even better than the palace of the British

embassy of the city was chosen and granted. I stayed in the huge palace

of a building between the ages of 11 and 16 every Easter (summers were

spent in Turkey), and remember him well as a person. It was 1954 and I

was still trying to adjust to the culture shock of life in an English

boarding school, and on learning that the two young matrons employed by

the school were going to Paris for a holiday, I mentioned, ‘you must have

tea, I’ll be at the Turkish embassy’. When in Paris I confessed to my

uncle what I had done, and that ‘we must cancel’, to which he responded,

‘certainly not, they must come!’ Numan sent the chauffeur driven huge

black Buick to pick them up from their hotel, and in the massive state

room, normally only opened up for heads of state, with butler present,

had tea with them in solid gold tea sets, left over from the Ottoman Empire

days.

Numan died in the late 1950s. He was almost unique for his day for he

would welcome the opportunity of meeting people of totally different backgrounds,

such as the Papal apostolic representative in Istanbul during WWII (1935-1944),

the Monsignor (Angelo Giuseppe) Roncalli, who was later to become to papal

nuncio in Paris, cardinal archbishop of Venice and finally the Pope

John XXIII in 1958. These two men would meet for tea at home, and

converse in French. Numan Menemencioğlu was pragmatist, a patriot

and also a humanist, allowing the free passage of 100,000

Jews escaping the Holocaust via Istanbul - info [There exists a dvd

available covering this subject, in which Mr. Streater was also interviewed].

I have a picture dated around 1909,

showing the Menemencioğlu family sitting in front of the family house,

probably long since destroyed, somewhere in Pera, featuring Numan, his

brother Muvaffak, his newly married wife Catherina (née Laya, a

Greek lady of Constantinople, with a confident pose with arms folded,

that couldn’t mean pre-marriage), and his father Menemenlizade Rıfat

Bey. Marriages across the religious divide in those days were rare, and

it is interesting the anti-Christian sultan, Abdülhamit II gave his

consent. Menemenlizade Rıfat bey would be almost unique for his time

to allow his son to marry a Greek, and not only that but rising up to

speak on the big family table (as was the case in that time, with extended

relations all present) to scold family members who applied pressure on

the new bride to change her religion, referring her to as ‘kızım’

[my daughter] and telling them not to try to convert her to Islam.

Catherina lived till aged 97 in 1987, however a new generation of the

family that didn’t have the same understanding, applied pressure on the

old lady for conversion and this time I intervened and instructed them

on the arrangements for a Christian funeral when she died.

For my prep school, I went to a Turkish school (Ayşe abla in Ankara)

for 7 years, before being shipped off to public boarding school (Sherborne)

in England, and I remember that the likes of Whittalls looked down upon

us. Indeed, there was some ill-concealed fury when I won an exhibition

(scholarship) to Magdalen College, Oxford, when some of the more ‘aristocratic’

English families couldn’t get their children anywhere near such a place.

Since graduation I have worked in the same advertising and public relations

firm in London, though now on a free-lance basis. I should emphasise that

I get on perfectly well with the few Whittalls I get to see in London.

It is just that our Turkish family connection, plus the many artistic/literary

friends my parents had in Turkey, meant that we were simply not interested

in going the Levantine social route. I grew up with a multi-ethnic feeling,

thinking it was entirely normal, only to discover that it was highly unusual.

There is a family memorial is in the Crimean Memorial Church in Istanbul.

It is a brass plaque in memory of Joseph Streater, who was a Churchwarden

in that church circa the 1920s. It is down towards the crypt, rather than in the main

body of the church. I don’t know too much about Joseph Streater, who was

obviously an uncle, I think a brother of grandfather, as well as a successful local businessman and supporter

of the church. Joseph Streater is a bit of a mystery to me but clearly

he was a local figure of some substance. But I have no recollection of

ever hearing him referred to, or of any marriage/children. In addition my father had an elder brother Roland, who disappeared at an early age in the direction of Africa, and his descendents now live in South Africa. We have some little contact with them.

My father continued to work as a managing director of G&A Barker after

the war, however with the 1960 army coup, all business dried up and the

company was wound up. At the age of 50, with a small amount of severance

pay, father and family went to London, where by good fortune he met his

friend, the ex-RAF deputy judge-advocate general, Middle East, A.G. Somerhaugh,

who had married them in Cairo in 1941 and who was the chairman of a merchant

bank and gave him a job. Later when the bank became part of Lloyds bank

international, negotiations with the treasury had broken down, which would

have repercussions for the bank. Father said, ‘let me have a go’, and

seeing they would have nothing to loose, granted his wish, and his negotiation

skills perfected in Turkey had the desired result where both sides gave

something the other side wanted. After that father ‘could do no wrong’

with the company, and he had good relations with the Turkish embassy too.

Father died in 1977, aged 65 when on holiday in Turkey and like his father

is buried in the British sector of the Protestant cemetery of Feriköy

in Istanbul, and other relations of the family all within a few yards

of each other, quite close to the chapel in the centre of the cemetery.

The memorial service in the cemetery was well attended and both the Anglican

priest and I gave speeches. My atheist mother’s ashes were later smuggled

into the country (cremation is not allowed in Turkey) and have joined

father’s grave. The stand-up cross is marked ‘Jasper Sidney Streater’,

to which I recently had added ‘Nermin Menemencioğlu Streater’. My

parents chose the location of the house in Swiss Cottage, London, to stay

close to their social circle of friends who had also moved from Turkey,

the residence I continue to live with my wife.

I continue to take an active interest in the affairs of Turkey and have

developed a close relationship with numerous ambassadors to London (traditionally,

but maybe not today, considered the most vital and important posting,

thus usually selected from the cream of Turkey’s diplomatic corps), assisting

and advising many in a voluntary capacity to help further the interests

of Turkey abroad.

Notes: 1- In 2003 Mr Streater

has published an article in the culture magazine Cornucopia, entitled

‘The

quiet revolutionary’, about the life and times of Namık Kemal,

explaining how this poet through his writings introduced the idea of free

thought to the Ottoman Turks, leading to the rise of Young Turks and latterly

to the development of European style democracy in the country. Also in

the same publication, in 2001 he penned an article entitled ‘The

Monsignor and the Minister’.

2- My Streater keeps abreast of political developments in Turkey and is a regular contributor to an online Turkish language newspaper, ‘Açık Gazete [Open Newspaper]’, which includes an article published September 2006, covering his background with the title: ‘The one man Turkey lobby in England’. The 4 recent articles published by Osman comprise (translated titles): ‘From England... What? Are Turks European? (21 Nov. 2007)’, ‘From England... My Surname? Look what İnönü said? (26 Nov. 2007)’, ‘From England... The shame of those who call themselves English (4 Dec. 2007)’, ‘From England... The poor old Ottoman language (11 Dec. 2007)’, ‘From England... How can the [Film] Midnight Express be derailed? (19 Dec. 2007)’, ‘From England... Is 2008 [for Turkey] the EU year or the oh-oh year? (31 Dec. 2007)’, ‘A hotel poem by Yahya Kemal’ (6 Jan. 2008), ‘From England... Could there be a less considerate Englishman than this? - translation - (16 Jan. 2008)’, ‘AKP should show the Christians the same tolerance as shown by [the conqueror of Constantinople] Fatih (24 Jan. 2008)’.

3- As editor-in-chief, Osman Streater was instrumental in the launch of a new political magazine in the summer of 2009, ‘Turkey in Europe’, backing the bid of Turkey’s full membership of the EEC with many high profile writers and analysis - archived news:

4- In late 2009 Osman Streater began his new role as the editor of the English section of a bilingual weekly newspaper aimed at the Turkish community in London, the ‘Turkish Times’.

5- Unfortunately Mr Streater Chairman of the Saville Club (London) from 1990-1996, after a long illness, bravely borne, died on Friday evening 22nd November 2013. May he rest in peace - obituary by David Barchard: