What is a Levantine city?

It is defined by:

Geography

diplomacy

language

hybridity

pleasure

freedom

modernity

and vulnerability.

I Geography

The Levant, le Levant, il Levante, means, for Europeans, ‘where the sun rises’, like the words Orient and Anatolia: therefore, the eastern Mediterranean. Levant is a geographical word, free of national or religious connotations. It is defined not by states or nationalities but by the sea. Like Saint Petersburg and Odessa in the Russian Empire, the great Levantine cities Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut were ‘windows on the West’, ports more open and cosmopolitan than inland cities like Ankara, Damascus and Cairo. From the beginning they were part of an international system.

The Levant was made by ships – bringing trade, immigrants and ideas before 1900; in the twentieth century exporting people from Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut to new Levants abroad. The corniche or ‘Cordon’ along the sea in these cities was a key meeting-place, trading centre and arrivals and departures lounge.

Levantine cities were trading cities, integrated into the economic systems of Europe and south Asia. Smyrna exported figs and raisins; Alexandria cotton; Beirut emigrants to the Americas and Africa. People and business, not monuments, were their main attraction: the present was more important than the past. Thackeray wrote that he liked Smyrna, because it produced no ‘fatigue of sublimity’.

2 Diplomacy

A western name for an eastern area, the Levant is also a dialogue – at the heart of ‘the world’s debate’ between Christianity and Islam. The modern Levant was the result of one of the most successful alliances in history, for three centuries after 1535, between France and the Ottoman Empire, between the caliph of the Muslims and the Most Christian King. Deals came before ideals. It was based on international strategy, on the shared hostility of the two monarchies to Spain and the House of Austria.

After the alliance came the capitulations: agreements between the Ottoman and foreign governments which allowed foreigners to operate in the Ottoman Empire under their own legal systems. Commerce followed diplomacy. ‘Our Indies’ was the French description of the Levant. Marseille lived off the Levant trade. As a result of the French-Ottoman alliance, French consuls were appointed to all major cities in the region. More French books were published on the Levant than on the newly discovered continent of America. It was a very near East, where, thanks to Ottoman law and order, travel was relatively safe. It was integrated into the Grand Tour: the temples of Baalbek, north-east of Beirut, were visited and described before the temples of Paestum, south of Naples.

In the ‘years of the consuls’, the ports of the Levant became diarchies between foreign consuls and local officials. Consuls’ status was marked by the appointment of their own guards or kavasses, in elaborate uniforms, and ottoman Janissaries, as protection from insult or attack. In 1694, and 1770 consuls in Smyrna persuaded the commanders of the Venetian and Russian navies respectively, not to attack the city, in order to prevent reprisals by Muslims against local Christians.

Consuls acted both as servants of their own governments and as local power-brokers and transmitters of modern technology and information to local rulers. In Beirut the el-Khazen family used their position as French consuls or vice-consuls in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in order to strengthen their local power –base – and to urge the King of France to invade the area. In the nineteenth century the British consul in Beirut was visited by members of the Jumblatt dynasty who claimed the Druze wanted Britain to rule Lebanon ‘like India’. The Iranian consul in Beirut was already acting as a protector of the local Shia long before the Iranian revolution of 1978.

Consuls lived like monarchs; their power was compared to that of the Emperor of Russia. From 1882-1914 the British consul-general ran the British occupation of Egypt. Consuls started the first quarantine systems, organised a peaceful transfer of power from Turkey to Greece in Salonica in 1912, but failed to do the reverse in Smyrna in 1922. Today, as protection from their own governments, local businessmen still aspire to become consuls for foreign governments.

In addition to France, another foreign power, Britain played a determining role in the Levant. The Royal Navy stopped an Egyptian takeover of the region in 1840 and helped take Egypt in 1882. Britain helped create modern Greece, Lebanon, Egypt and Israel.

3 Language

The Levant was further defined by language. Another form of integration. Before the triumph of English, the Levant had two international languages. First was lingua franca, the simplified Italian ‘generalement entendue par toutes les cotes du Levant’, ‘qui a cours part tout le Levant entre les gens de Marine de la Mediterranee et les Marchands qui vont negocier au Levant et qui se fait entendre de toutes les nations’, as French travellers wrote. It was spoken by the Beys of Tunis and Tripoli; by sailors and slaves, merchants and admirals; the fishermen of Alexandria; Cervantes, Rousseau and Byron. Characteristic phrases are: ‘ven acqui’; ‘christiani star fourbi’: come here; Christians are cunning. Lingu franca was proof of the inhabitants’ desire and need to communicate with Europeans. They were not cut off from the outside world.

From 1840, thanks to the spread of French schools run by Catholic teaching Orders and the growth of travel, French, then the world language, became the second language of the Levant. It was spoken by pashas, viziers and sultans; Mustafa Kemal, King Fouad of Egypt, George Seferis; It was an official language of the municipalities of Alexandria and Beirut. The Levant was becoming culturally integrated with Europe. Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut were each called the Paris of the Levant or the Middle East. French schools in these cities included those run by Jesuits; the Order of Notre Dame de Sion; the soeurs de Besancon; the Freres des ecoles chretiennes; and the government Mission laique. They were attended by Muslims and Jews as well as Christians. Who knows how many foreign-organised universities there are today in Beirut ? Thirty? Forty?

There are still major French newspapers and universities in Beirut and many Lebanese write in French and speak it at home. Young Turk revolutionaries regarded Paris as the Mecca of freedom and progress. Foreign institutions like International College in Smyrna, the Universite Saint Joseph in Beirut, the American University of Beirut and Victoria College in Alexandria ‘the Eton of the Middle East’, gave pupils the weapons with which to fight the cultural imperialism they represented. Mustafa Kemal would introduce the laws of the Third Republic, including its anti-religious laws, into modern Turkey. Another form of integration with the outside world.

4 Hybridity

Hybridity and multiple identities were another characteristic of the Levant. If as the Lebanese American historian William Haddad has written, ‘the nation state is the prison of the mind’, the Levant was a jail break. The Ottoman Empire enforced few of the restrictions and regulations considered necessary by nation states. There were no ghettos. Travellers were impressed and often attracted by the variety of races and costumes in these cities and the juxtaposition of mosques, churches and synagogues, inconceivable in European cities before 1970.

Many people had multiple identities: the Baltazzi family of bankers in Smyrna were Greek, Ottoman and European. Sabbatai Sevi, the ‘false Messiah’ of Smyrna, founded his own religion with Christian and Muslim as well as Jewish elements. The Dönme / Sebataycı, as some of them were called, are still an important element in Izmir and Istanbul. The Shehabs of Beirut had Christian, Muslim and Druze branches, as they still do. The Mohammed Ali dynasty ruling in Egypt were Ottoman, Egyptian and in some of their habits and education European. Palaces and houses like Ras el tine palace in Alexandria and the Maison Pharaoun in Beirut blended styles and objects from different countries and centuries. Smyrna seemed to some visiting Turks like a foreign country.

As long as governments protected hybridity, it worked as well as uniformity: Levantine cities did not experience the violent revolutions of nineteenth century Paris or twentieth century Vienna. However hybridity, which had suited most Ottoman governors, and the Mohammed Ali dynasty in Egypt, alienated the nationalist leaders of the twentieth century. Disintegration set in. Smyrna was burnt after its conquest by the Turkish army in 1922: Mustafa Kemal found it marble and left it ashes. Many Smyrniots left for Alexandria or Beirut.

Tel Aviv was founded in opposition to cosmopolitan Jaffa, as a Jewish city without ‘goys’: Ben Gurion later denounced ‘the spirit of the Levant which ruins individuals and societies’. Israel has had a devastating effect on Levantine cities, both indirectly by its heightening of tensions in the region, and encouragement of Jews to immigrate to Israel, and directly by invasions. It thrice attacked Lebanon, in 1976, 1982 and 2006. It attacked Egypt in 1956, in combination with Britain and France. Thereafter, Nasser, himself born and educated in Alexandria, encouraged Alexandrians of foreign origin to leave.

5 Pleasure

The cities of the Levant were synonymous with a horizontal form of integration: sexual freedom greater than in western cities. Travellers admired the ‘freedom of Turkish living’. The women of Pera, the Levantine district of Constantinople north of the Golden Horn, would, it was said make a saint a devil. The women of Smyrna combined western elegance with eastern allure. Norman Douglas called it in 1885 ‘the most enjoyable place on earth’. With its cafes and orchestras, the Smyrna Cordon according to the Turkish novelist Naci Cundem would make the most depressed person laugh. The women of Alexandria, ‘modern to the tips of their delicate little feet’ with ‘a furious desire to break with every prejudice, to taste every sensation’ were, according to Fernand Leprette, one of its main attractions.

Cavafy, the poet of Alexandria, had other tastes. The first openly homosexual poet of the twentieth century, he wrote that in a room above a ‘suspect taverna’, ‘on that humble bed I had love’s body, had those intoxicating lips’.

Music was another Levantine pleasure. As Lisbon created fado, and New Orleans jazz, Smyrna, more than any other Levantine city, created its own sound: a blend of modern Greek and Turkish music called Smyrnaika or rebetiko. It was the music of rebels, particularly appreciated by the qabadays (Turkish) or dais (Greek), the toughs who, as in other Mediterranean ports, worked, gambled and fought with each other. A Papazoglu, a musician in one of the cafes on the Cordon, remembered; ‘we had to know a song or two from each nationality to please the customers: We played Jewish and Armenian and Arab music. We were citizens of the world, you see.’

Rebetiko songs mixed western polyphony and eastern monophony and described the sufferings of the poor nd prisoners, the torments of love, or the pleasures of hashish.

Won’t you tell, won’t you tell me

Where hashish is sold?

The dervishes sell it

In the upper districts.1

In Smyrna songs women were coquettes or tyrants:

‘Your black eyes that gaze at me.

My dear, lower them, because they are killing me.’

…

You stay up all night at the cafes chantant, drinking beer, Oh!

And the rest of us you are treating as green caviare.

While Alexandria had no special music, Beirut has become the capital of Arab pop, with singers like Magda Rumi, Nancy Ajram and the incomparable Fairuz.

6 Modernity

Levantine cities helped integrate their hinterlands into the modern world. Modern Turkey was born in the Levantine port of Salonica, birthplace of Mustafa Kemal, where the Young Turk revolution broke out in 1908, helped by the protection of foreign consuls and the proximity of foreign states. Smyrna had the first newspaper, American schools, railway, electricity and cinema in the Ottoman Empire and some of its most modern women, like Latife hanim, wife of Mustafa Kemal. She came from the Ushakligil family of merchants, another of whom, the writer Halid Ziya, appreciated Smyrna precisely because it had so many foreigners and foreign schools, and felt like a foreign country. ‘Smyrna illuminates like a beacon all the other provinces of the Ottoman Empire’, wrote the Austrian consul-general Charles de Scherzer. Alexandria was a dynamo of the Egyptian economy and had the country’s first feminist newspaper and brewery.

In Beirut before 1975 wrote Edward Said ‘Everything seemed possible, every idea every identity’. For Mai Ghoussoub, ‘Beirut exuded optimism and the most disadvantaged believed in its promises’. In part because other Arab cities were run by police states, Beirut became for Arabs a synonym of modernity and freedom, ‘the lady of the world’, ‘our only star’. It still is. ‘Beirut is total and absolute freedom’, writes Zeena al Khalil. It remains the Arab world’s publishing centre, with more and freer magazines and newspapers than any other city. It is also again becoming a tourist and financial centre. One Hezbollah leader calls it ‘a lung through which Iran breathes.’ Who knows what the future holds for Beirut, now that the Arab spring is bringing the area back to life?

7 Vulnerability

Levantine cities reflect the tensions between ports and hinterlands, and cities and states, which have also affected other great port cities like New York, Amsterdam, Marseille, Seville, Shanghai and Singapore: the hidden wiring of history. In 1814, for example, in a rare case of a French provincial city, rather than Paris, successfully taking a political initiative, Bordeaux declared in favour of the Bourbons, against Napoleon, because the former would favour the city’s trade. One port helped cause national regime change. Marseille and Odessa encouraged the Greek revolution of 1821, Hamburg would lead the German revolution of 1918.

In 1826 Beirut was described as a republic of merchants, independent of the governor in Damascus. This phenomenon can still be observed today. Beirut is still at logger-heads with Damascus. The coasts of Turkey, and the city of Izmir, are the last bastions of the secular CHP against the AKP government which is all powerful in the rest of the country. In other cities the muezzin is deafening; in Izmir almost inaudible. At different times Smyrna, Beirut and Alexandria have seemed, as has been said of New York, like ‘islands off the coast of Europe.’

Smyrna merchants dreamt of founding a city state. Alexandria in 1882, Beirut in 1918-20, Smyrna in 1919-22, were used as bases, by the British, French and Greek armies respectively, from which to conquer those cities’ hinterlands – with the support of many of the cities’ inhabitants. The city as a force for change. Demonstrators in Tunis in February 2011 said: ‘this is a maritime country: we are sailors and we’ve always been open to the outside world’. Tunisia will remain a land of beer and bikinis, not fanatics. The Arab spring of 2011 shows these countries’ desire to reconnect with the outside world and their own cosmopolitan past.

However, none of these cities had a strong, autonomous administration. Municipalities, founded in Smyrna and Beirut in 1868 and in Alexandria in 1892, were weak and divided. There was no Venetian republic or Hanseatic League in the Levant.

Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut were also cities on the edge of disintegration; racial or religious hatred was ready to erupt. They show how quickly cities can become, literally, jungles (both in the ‘burnt areas’ of post-1922 Smyrna and in civil-war Beirut, when trees and weeds burst through the asphalt of the main square). Unlike Renaissance Florence, or revolutionary Paris, Levantine cities had no armies of their own to protect them and enable them to influence the nation. It was the Paris National Guard which enabled Paris to act as an independent political force in France: to seize Louis XVI and the royal family in 1789, to lead the revolutions of 1830, 1848 and 1870, and defy the rest of France during the Paris commune in 1871.

Smyrna was said to enjoy ten years of massacre, followed by thirty years of merriment. There were outbreaks of race hate there between Greeks and Turks in 1770, 1797 and 1821 – a long peace marked by the visits of two Ottoman Sultans, in 1850 and 1863 – then the final holocaust of 1922: the Cordon became a killing-field of Greeks and Armenians by Turks. One month later no Greeks or Armenians remained. The Smyrna carnival, once famous throughout the Levant, has never been permitted since – at least in public.

Alexandria had a less brutal history, but there were race riots and the British bombardment in 1882, more race riots in 1921; E.M. Forster was wrong to write that Alexandrians did not take differences of race seriously. Between 1945 and 1975 most non-Muslims left. Beirut, hailed as a miracle of peace in the 1960’s, was shattered by fifteen years of civil war after 1975. People might be killed because of the religion recorded on their identity card. Today, again, it may be on the edge of another explosion. As in Egypt, much depends on the army.

The Levant also shows the vulnerability of wealth. People were turned from bourgeois to beggars overnight by the fire of Smyrna, the nationalisations of Nasser or the civil-war bank robberies of Beirut. Beirut today is threatened by the nationalist governments of Damascus, Tel Aviv and Tehran and the weakness of the Lebanese army and police: ‘no one wants Beirut to become a jungle’, said the Minister of Information on 3 August 2010, after the latest fighting. Anything goes, both in politics and in private lives. In a recent survey of 18-25 year olds by the American University, one in three say they hate the young of other communities, and would refuse to marry them; all want to leave. The city awaits with fear the results of the international investigation into the murder of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

By its continued hybridity, multilingualism, modernity and vulnerability, and by the continued importance of foreign powers in its internal affairs – shown by the international tribunal, and the visits of Presidents Chirac in 2005 and Ahmedinejad in 2010 - Beirut is the last great Levantine city. No one group dominates.

Lebanon’s international connections survive. Orthodox Lebanese can easily become citizens of Greece as they share the same religion. Shia connections with Iran predate the revolution: Shia religious leaders were also consuls of Qajar Iran. Indeed Beirut is becoming more Levantine by the addition of more communities from more countries: Armenia, Palestine, India, Iraq, the Philippines, Copts and Assyrians. This mixed Levantine character, rather than being a source of weakness, may be a source of strength in the new global economy.

Conclusion

‘The city will always pursue you’, wrote Cavafy.

‘You will walk

the same streets, grow old in the same neighbourhoods

will turn grey in these same houses.

You will always end up in this city.’

The Levant is ceasing to be one geographical area. Modern London, Paris, New York, and Dubai, with their varieties of races religions and languages, are new Levantine cities, increasingly different from their hinterlands. London now seems like another country, different to the rest of England.

Moreover they have welcomed, among their millions of immigrants, people from Smyrna, Beirut and Alexandria like Mohammed al Fayed, Alec Issigonis the designer of the Mini, Omar Sharif, Edouard Balladur, from a French-protected Armenian Catholic family of Smyrna; the many Lebanese writing in French who have settled in Paris like Andree Chedid, Albert Cossery, Dominique Edde, Amin Maalouf.

Ben Gurion was wrong. The nation state was a twentieth century interlude. Levantine cities are the future as well as the past. Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut are all trying to revive their cosmopolitan past. Istanbul itself, for the first time since 1943, allows carnival revellers to wind through the streets: ‘the only public carnival in the Muslim world’.2 There was a conference on Levantines in Izmir in November 2010, there will be one in Mersin in October 2011. Levantines are popular. We are all Levantines now.

Note: 1- Philip Mansel has recently published ‘Levant: Splendour and Catastrphe on the Mediterranean’ - 2010, Philip Mansel (publisher: John Murray) - details & interview - purchase options. Earlier Philip Mansel also published Constantinople - City of world’s desire 1453-1924, John Murray books 1995 - segment - interview

2- Mr Mansel was recently (2011) interviewed as part of a historical documentary by Srdan Segaric for Croatian TV, on the “Croatians on the Bosphorus”.

3- Philip Mansel lecture on video “What is a Levantine City? From Smyrna to Izmir”, based on his latest book, 4th May 2011.

It is defined by:

Geography

diplomacy

language

hybridity

pleasure

freedom

modernity

and vulnerability.

I Geography

The Levant, le Levant, il Levante, means, for Europeans, ‘where the sun rises’, like the words Orient and Anatolia: therefore, the eastern Mediterranean. Levant is a geographical word, free of national or religious connotations. It is defined not by states or nationalities but by the sea. Like Saint Petersburg and Odessa in the Russian Empire, the great Levantine cities Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut were ‘windows on the West’, ports more open and cosmopolitan than inland cities like Ankara, Damascus and Cairo. From the beginning they were part of an international system.

The Levant was made by ships – bringing trade, immigrants and ideas before 1900; in the twentieth century exporting people from Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut to new Levants abroad. The corniche or ‘Cordon’ along the sea in these cities was a key meeting-place, trading centre and arrivals and departures lounge.

Levantine cities were trading cities, integrated into the economic systems of Europe and south Asia. Smyrna exported figs and raisins; Alexandria cotton; Beirut emigrants to the Americas and Africa. People and business, not monuments, were their main attraction: the present was more important than the past. Thackeray wrote that he liked Smyrna, because it produced no ‘fatigue of sublimity’.

2 Diplomacy

A western name for an eastern area, the Levant is also a dialogue – at the heart of ‘the world’s debate’ between Christianity and Islam. The modern Levant was the result of one of the most successful alliances in history, for three centuries after 1535, between France and the Ottoman Empire, between the caliph of the Muslims and the Most Christian King. Deals came before ideals. It was based on international strategy, on the shared hostility of the two monarchies to Spain and the House of Austria.

After the alliance came the capitulations: agreements between the Ottoman and foreign governments which allowed foreigners to operate in the Ottoman Empire under their own legal systems. Commerce followed diplomacy. ‘Our Indies’ was the French description of the Levant. Marseille lived off the Levant trade. As a result of the French-Ottoman alliance, French consuls were appointed to all major cities in the region. More French books were published on the Levant than on the newly discovered continent of America. It was a very near East, where, thanks to Ottoman law and order, travel was relatively safe. It was integrated into the Grand Tour: the temples of Baalbek, north-east of Beirut, were visited and described before the temples of Paestum, south of Naples.

In the ‘years of the consuls’, the ports of the Levant became diarchies between foreign consuls and local officials. Consuls’ status was marked by the appointment of their own guards or kavasses, in elaborate uniforms, and ottoman Janissaries, as protection from insult or attack. In 1694, and 1770 consuls in Smyrna persuaded the commanders of the Venetian and Russian navies respectively, not to attack the city, in order to prevent reprisals by Muslims against local Christians.

Consuls acted both as servants of their own governments and as local power-brokers and transmitters of modern technology and information to local rulers. In Beirut the el-Khazen family used their position as French consuls or vice-consuls in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in order to strengthen their local power –base – and to urge the King of France to invade the area. In the nineteenth century the British consul in Beirut was visited by members of the Jumblatt dynasty who claimed the Druze wanted Britain to rule Lebanon ‘like India’. The Iranian consul in Beirut was already acting as a protector of the local Shia long before the Iranian revolution of 1978.

Consuls lived like monarchs; their power was compared to that of the Emperor of Russia. From 1882-1914 the British consul-general ran the British occupation of Egypt. Consuls started the first quarantine systems, organised a peaceful transfer of power from Turkey to Greece in Salonica in 1912, but failed to do the reverse in Smyrna in 1922. Today, as protection from their own governments, local businessmen still aspire to become consuls for foreign governments.

In addition to France, another foreign power, Britain played a determining role in the Levant. The Royal Navy stopped an Egyptian takeover of the region in 1840 and helped take Egypt in 1882. Britain helped create modern Greece, Lebanon, Egypt and Israel.

3 Language

The Levant was further defined by language. Another form of integration. Before the triumph of English, the Levant had two international languages. First was lingua franca, the simplified Italian ‘generalement entendue par toutes les cotes du Levant’, ‘qui a cours part tout le Levant entre les gens de Marine de la Mediterranee et les Marchands qui vont negocier au Levant et qui se fait entendre de toutes les nations’, as French travellers wrote. It was spoken by the Beys of Tunis and Tripoli; by sailors and slaves, merchants and admirals; the fishermen of Alexandria; Cervantes, Rousseau and Byron. Characteristic phrases are: ‘ven acqui’; ‘christiani star fourbi’: come here; Christians are cunning. Lingu franca was proof of the inhabitants’ desire and need to communicate with Europeans. They were not cut off from the outside world.

From 1840, thanks to the spread of French schools run by Catholic teaching Orders and the growth of travel, French, then the world language, became the second language of the Levant. It was spoken by pashas, viziers and sultans; Mustafa Kemal, King Fouad of Egypt, George Seferis; It was an official language of the municipalities of Alexandria and Beirut. The Levant was becoming culturally integrated with Europe. Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut were each called the Paris of the Levant or the Middle East. French schools in these cities included those run by Jesuits; the Order of Notre Dame de Sion; the soeurs de Besancon; the Freres des ecoles chretiennes; and the government Mission laique. They were attended by Muslims and Jews as well as Christians. Who knows how many foreign-organised universities there are today in Beirut ? Thirty? Forty?

There are still major French newspapers and universities in Beirut and many Lebanese write in French and speak it at home. Young Turk revolutionaries regarded Paris as the Mecca of freedom and progress. Foreign institutions like International College in Smyrna, the Universite Saint Joseph in Beirut, the American University of Beirut and Victoria College in Alexandria ‘the Eton of the Middle East’, gave pupils the weapons with which to fight the cultural imperialism they represented. Mustafa Kemal would introduce the laws of the Third Republic, including its anti-religious laws, into modern Turkey. Another form of integration with the outside world.

4 Hybridity

Hybridity and multiple identities were another characteristic of the Levant. If as the Lebanese American historian William Haddad has written, ‘the nation state is the prison of the mind’, the Levant was a jail break. The Ottoman Empire enforced few of the restrictions and regulations considered necessary by nation states. There were no ghettos. Travellers were impressed and often attracted by the variety of races and costumes in these cities and the juxtaposition of mosques, churches and synagogues, inconceivable in European cities before 1970.

Many people had multiple identities: the Baltazzi family of bankers in Smyrna were Greek, Ottoman and European. Sabbatai Sevi, the ‘false Messiah’ of Smyrna, founded his own religion with Christian and Muslim as well as Jewish elements. The Dönme / Sebataycı, as some of them were called, are still an important element in Izmir and Istanbul. The Shehabs of Beirut had Christian, Muslim and Druze branches, as they still do. The Mohammed Ali dynasty ruling in Egypt were Ottoman, Egyptian and in some of their habits and education European. Palaces and houses like Ras el tine palace in Alexandria and the Maison Pharaoun in Beirut blended styles and objects from different countries and centuries. Smyrna seemed to some visiting Turks like a foreign country.

As long as governments protected hybridity, it worked as well as uniformity: Levantine cities did not experience the violent revolutions of nineteenth century Paris or twentieth century Vienna. However hybridity, which had suited most Ottoman governors, and the Mohammed Ali dynasty in Egypt, alienated the nationalist leaders of the twentieth century. Disintegration set in. Smyrna was burnt after its conquest by the Turkish army in 1922: Mustafa Kemal found it marble and left it ashes. Many Smyrniots left for Alexandria or Beirut.

Tel Aviv was founded in opposition to cosmopolitan Jaffa, as a Jewish city without ‘goys’: Ben Gurion later denounced ‘the spirit of the Levant which ruins individuals and societies’. Israel has had a devastating effect on Levantine cities, both indirectly by its heightening of tensions in the region, and encouragement of Jews to immigrate to Israel, and directly by invasions. It thrice attacked Lebanon, in 1976, 1982 and 2006. It attacked Egypt in 1956, in combination with Britain and France. Thereafter, Nasser, himself born and educated in Alexandria, encouraged Alexandrians of foreign origin to leave.

5 Pleasure

The cities of the Levant were synonymous with a horizontal form of integration: sexual freedom greater than in western cities. Travellers admired the ‘freedom of Turkish living’. The women of Pera, the Levantine district of Constantinople north of the Golden Horn, would, it was said make a saint a devil. The women of Smyrna combined western elegance with eastern allure. Norman Douglas called it in 1885 ‘the most enjoyable place on earth’. With its cafes and orchestras, the Smyrna Cordon according to the Turkish novelist Naci Cundem would make the most depressed person laugh. The women of Alexandria, ‘modern to the tips of their delicate little feet’ with ‘a furious desire to break with every prejudice, to taste every sensation’ were, according to Fernand Leprette, one of its main attractions.

Cavafy, the poet of Alexandria, had other tastes. The first openly homosexual poet of the twentieth century, he wrote that in a room above a ‘suspect taverna’, ‘on that humble bed I had love’s body, had those intoxicating lips’.

Music was another Levantine pleasure. As Lisbon created fado, and New Orleans jazz, Smyrna, more than any other Levantine city, created its own sound: a blend of modern Greek and Turkish music called Smyrnaika or rebetiko. It was the music of rebels, particularly appreciated by the qabadays (Turkish) or dais (Greek), the toughs who, as in other Mediterranean ports, worked, gambled and fought with each other. A Papazoglu, a musician in one of the cafes on the Cordon, remembered; ‘we had to know a song or two from each nationality to please the customers: We played Jewish and Armenian and Arab music. We were citizens of the world, you see.’

Rebetiko songs mixed western polyphony and eastern monophony and described the sufferings of the poor nd prisoners, the torments of love, or the pleasures of hashish.

Won’t you tell, won’t you tell me

Where hashish is sold?

The dervishes sell it

In the upper districts.1

In Smyrna songs women were coquettes or tyrants:

‘Your black eyes that gaze at me.

My dear, lower them, because they are killing me.’

…

You stay up all night at the cafes chantant, drinking beer, Oh!

And the rest of us you are treating as green caviare.

While Alexandria had no special music, Beirut has become the capital of Arab pop, with singers like Magda Rumi, Nancy Ajram and the incomparable Fairuz.

6 Modernity

Levantine cities helped integrate their hinterlands into the modern world. Modern Turkey was born in the Levantine port of Salonica, birthplace of Mustafa Kemal, where the Young Turk revolution broke out in 1908, helped by the protection of foreign consuls and the proximity of foreign states. Smyrna had the first newspaper, American schools, railway, electricity and cinema in the Ottoman Empire and some of its most modern women, like Latife hanim, wife of Mustafa Kemal. She came from the Ushakligil family of merchants, another of whom, the writer Halid Ziya, appreciated Smyrna precisely because it had so many foreigners and foreign schools, and felt like a foreign country. ‘Smyrna illuminates like a beacon all the other provinces of the Ottoman Empire’, wrote the Austrian consul-general Charles de Scherzer. Alexandria was a dynamo of the Egyptian economy and had the country’s first feminist newspaper and brewery.

In Beirut before 1975 wrote Edward Said ‘Everything seemed possible, every idea every identity’. For Mai Ghoussoub, ‘Beirut exuded optimism and the most disadvantaged believed in its promises’. In part because other Arab cities were run by police states, Beirut became for Arabs a synonym of modernity and freedom, ‘the lady of the world’, ‘our only star’. It still is. ‘Beirut is total and absolute freedom’, writes Zeena al Khalil. It remains the Arab world’s publishing centre, with more and freer magazines and newspapers than any other city. It is also again becoming a tourist and financial centre. One Hezbollah leader calls it ‘a lung through which Iran breathes.’ Who knows what the future holds for Beirut, now that the Arab spring is bringing the area back to life?

7 Vulnerability

Levantine cities reflect the tensions between ports and hinterlands, and cities and states, which have also affected other great port cities like New York, Amsterdam, Marseille, Seville, Shanghai and Singapore: the hidden wiring of history. In 1814, for example, in a rare case of a French provincial city, rather than Paris, successfully taking a political initiative, Bordeaux declared in favour of the Bourbons, against Napoleon, because the former would favour the city’s trade. One port helped cause national regime change. Marseille and Odessa encouraged the Greek revolution of 1821, Hamburg would lead the German revolution of 1918.

In 1826 Beirut was described as a republic of merchants, independent of the governor in Damascus. This phenomenon can still be observed today. Beirut is still at logger-heads with Damascus. The coasts of Turkey, and the city of Izmir, are the last bastions of the secular CHP against the AKP government which is all powerful in the rest of the country. In other cities the muezzin is deafening; in Izmir almost inaudible. At different times Smyrna, Beirut and Alexandria have seemed, as has been said of New York, like ‘islands off the coast of Europe.’

Smyrna merchants dreamt of founding a city state. Alexandria in 1882, Beirut in 1918-20, Smyrna in 1919-22, were used as bases, by the British, French and Greek armies respectively, from which to conquer those cities’ hinterlands – with the support of many of the cities’ inhabitants. The city as a force for change. Demonstrators in Tunis in February 2011 said: ‘this is a maritime country: we are sailors and we’ve always been open to the outside world’. Tunisia will remain a land of beer and bikinis, not fanatics. The Arab spring of 2011 shows these countries’ desire to reconnect with the outside world and their own cosmopolitan past.

However, none of these cities had a strong, autonomous administration. Municipalities, founded in Smyrna and Beirut in 1868 and in Alexandria in 1892, were weak and divided. There was no Venetian republic or Hanseatic League in the Levant.

Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut were also cities on the edge of disintegration; racial or religious hatred was ready to erupt. They show how quickly cities can become, literally, jungles (both in the ‘burnt areas’ of post-1922 Smyrna and in civil-war Beirut, when trees and weeds burst through the asphalt of the main square). Unlike Renaissance Florence, or revolutionary Paris, Levantine cities had no armies of their own to protect them and enable them to influence the nation. It was the Paris National Guard which enabled Paris to act as an independent political force in France: to seize Louis XVI and the royal family in 1789, to lead the revolutions of 1830, 1848 and 1870, and defy the rest of France during the Paris commune in 1871.

Smyrna was said to enjoy ten years of massacre, followed by thirty years of merriment. There were outbreaks of race hate there between Greeks and Turks in 1770, 1797 and 1821 – a long peace marked by the visits of two Ottoman Sultans, in 1850 and 1863 – then the final holocaust of 1922: the Cordon became a killing-field of Greeks and Armenians by Turks. One month later no Greeks or Armenians remained. The Smyrna carnival, once famous throughout the Levant, has never been permitted since – at least in public.

Alexandria had a less brutal history, but there were race riots and the British bombardment in 1882, more race riots in 1921; E.M. Forster was wrong to write that Alexandrians did not take differences of race seriously. Between 1945 and 1975 most non-Muslims left. Beirut, hailed as a miracle of peace in the 1960’s, was shattered by fifteen years of civil war after 1975. People might be killed because of the religion recorded on their identity card. Today, again, it may be on the edge of another explosion. As in Egypt, much depends on the army.

The Levant also shows the vulnerability of wealth. People were turned from bourgeois to beggars overnight by the fire of Smyrna, the nationalisations of Nasser or the civil-war bank robberies of Beirut. Beirut today is threatened by the nationalist governments of Damascus, Tel Aviv and Tehran and the weakness of the Lebanese army and police: ‘no one wants Beirut to become a jungle’, said the Minister of Information on 3 August 2010, after the latest fighting. Anything goes, both in politics and in private lives. In a recent survey of 18-25 year olds by the American University, one in three say they hate the young of other communities, and would refuse to marry them; all want to leave. The city awaits with fear the results of the international investigation into the murder of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri.

By its continued hybridity, multilingualism, modernity and vulnerability, and by the continued importance of foreign powers in its internal affairs – shown by the international tribunal, and the visits of Presidents Chirac in 2005 and Ahmedinejad in 2010 - Beirut is the last great Levantine city. No one group dominates.

Lebanon’s international connections survive. Orthodox Lebanese can easily become citizens of Greece as they share the same religion. Shia connections with Iran predate the revolution: Shia religious leaders were also consuls of Qajar Iran. Indeed Beirut is becoming more Levantine by the addition of more communities from more countries: Armenia, Palestine, India, Iraq, the Philippines, Copts and Assyrians. This mixed Levantine character, rather than being a source of weakness, may be a source of strength in the new global economy.

Conclusion

‘The city will always pursue you’, wrote Cavafy.

‘You will walk

the same streets, grow old in the same neighbourhoods

will turn grey in these same houses.

You will always end up in this city.’

The Levant is ceasing to be one geographical area. Modern London, Paris, New York, and Dubai, with their varieties of races religions and languages, are new Levantine cities, increasingly different from their hinterlands. London now seems like another country, different to the rest of England.

Moreover they have welcomed, among their millions of immigrants, people from Smyrna, Beirut and Alexandria like Mohammed al Fayed, Alec Issigonis the designer of the Mini, Omar Sharif, Edouard Balladur, from a French-protected Armenian Catholic family of Smyrna; the many Lebanese writing in French who have settled in Paris like Andree Chedid, Albert Cossery, Dominique Edde, Amin Maalouf.

Ben Gurion was wrong. The nation state was a twentieth century interlude. Levantine cities are the future as well as the past. Smyrna, Alexandria and Beirut are all trying to revive their cosmopolitan past. Istanbul itself, for the first time since 1943, allows carnival revellers to wind through the streets: ‘the only public carnival in the Muslim world’.2 There was a conference on Levantines in Izmir in November 2010, there will be one in Mersin in October 2011. Levantines are popular. We are all Levantines now.

1- Gauntlett, ‘Between Orientalism and Occidentalism’ in R. Hirschhon ed., Crossing the Aegean, p 251.

2- International Herald Tribune 5 March 2011.

2- International Herald Tribune 5 March 2011.

Note: 1- Philip Mansel has recently published ‘Levant: Splendour and Catastrphe on the Mediterranean’ - 2010, Philip Mansel (publisher: John Murray) - details & interview - purchase options. Earlier Philip Mansel also published Constantinople - City of world’s desire 1453-1924, John Murray books 1995 - segment - interview

2- Mr Mansel was recently (2011) interviewed as part of a historical documentary by Srdan Segaric for Croatian TV, on the “Croatians on the Bosphorus”.

3- Philip Mansel lecture on video “What is a Levantine City? From Smyrna to Izmir”, based on his latest book, 4th May 2011.

|

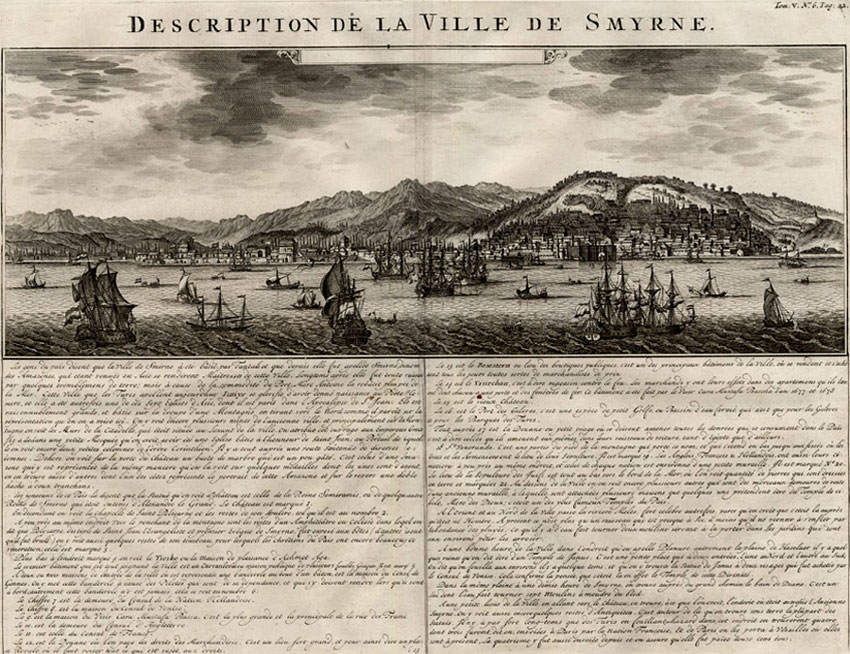

An etching by geographer Henri Abraham Chatelain (1684-1743) published in Amsterdam in 1714, in a book entitled ‘Atlas Historique et Méthodique’ (part of a 7 volume series), under the section - Description de la ville de Smyrne