1)

The Historical sites

Walking between the chapels of the Montenero House of Fame (Famedio) in Leghorn (archive view - zoomable map) or in the orthodox Greek Cemetery of Mastacchi street, trying to investigate by that indelible identity card which is a grave stone or a burial monument, we can often read “Scio” as a birth place of some renowned personages, members of ‘Levantine’ families of Leghorn: Rodocanachi, Castelli, Mavrogordato, Reggio, Guiducci.

Walking between the chapels of the Montenero House of Fame (Famedio) in Leghorn (archive view - zoomable map) or in the orthodox Greek Cemetery of Mastacchi street, trying to investigate by that indelible identity card which is a grave stone or a burial monument, we can often read “Scio” as a birth place of some renowned personages, members of ‘Levantine’ families of Leghorn: Rodocanachi, Castelli, Mavrogordato, Reggio, Guiducci.

|

The

above named families were Catholic yet they came from majority Ortodox Chios,

a cultural minority in both lands, but they were typically able to bridge

gaps through trade and entrepeneurship. Leghorn was a very complex community

which included political exiles such as Polish nationalists, Greek Ortodox diaspora and French

citizens with anti-Napoleonic sentiments.

Scio is maybe the interpretation of Xiois, the way it would be read in Italian, the word “Chios” written in Greek alphabet. In this island of the Aegean Sea, 9 sea miles from the Turkish shore, and not too far from the important port of Smyrna, we realized that there is still an interest in historical researches, covering events before, during and following the Greek war of independence. It was this event that upset the political and economic order on which the ancient Genoan family of Giustiniani had established themselves in the Island, during their tenure that lasting about six centuries. The resulting blood-letting ended this order, but their legacy still survives in traces that are still present in many domestic buildings of Chios and in some religious buildings, like the wonderful Nea Moni Monastry.

Scio is maybe the interpretation of Xiois, the way it would be read in Italian, the word “Chios” written in Greek alphabet. In this island of the Aegean Sea, 9 sea miles from the Turkish shore, and not too far from the important port of Smyrna, we realized that there is still an interest in historical researches, covering events before, during and following the Greek war of independence. It was this event that upset the political and economic order on which the ancient Genoan family of Giustiniani had established themselves in the Island, during their tenure that lasting about six centuries. The resulting blood-letting ended this order, but their legacy still survives in traces that are still present in many domestic buildings of Chios and in some religious buildings, like the wonderful Nea Moni Monastry.

|

|

|

|

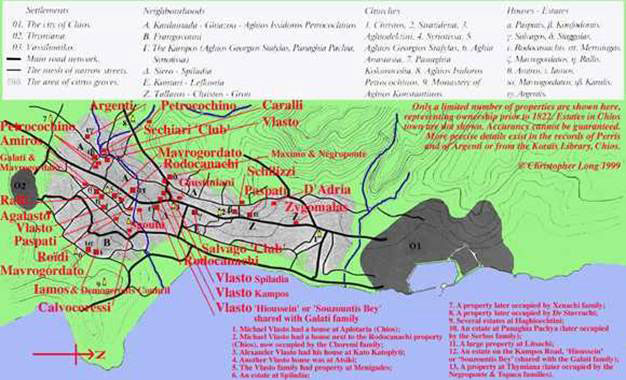

Chios

was ruled by its own characteristic system of government, based on the

hierarchy of the most important Levantine families, distributed in a

fan-shaped zone origined from the main site, having as fulcrum of the

fan, the harbour, the Fortress, the factories and those whose residences

were in the city centre and in the Kampos zone. On the fringes of power

were families of lower status, whose responsabilities extended to the

control and administration of agricultural production and the collection

of the Lentisk mastic. The elite government system was enlarge with

time, but was retained within the noble families, who were keen to preserve

the monopoly of power. One important evidence is given by the discorvery

made by Philippe Argenti, native of Chios and teacher at the Sorbonne

University in Paris, who composed a “Golden Book” of the Chiot Nobility

starting from an “evamngeliarie” property of the Mavrogordato-Scarlato

family. Chios was ruled by Giustiniani and other Maona families who

joined those coming from Genoa, reaching Chios from different Mediterranean

centres.

|

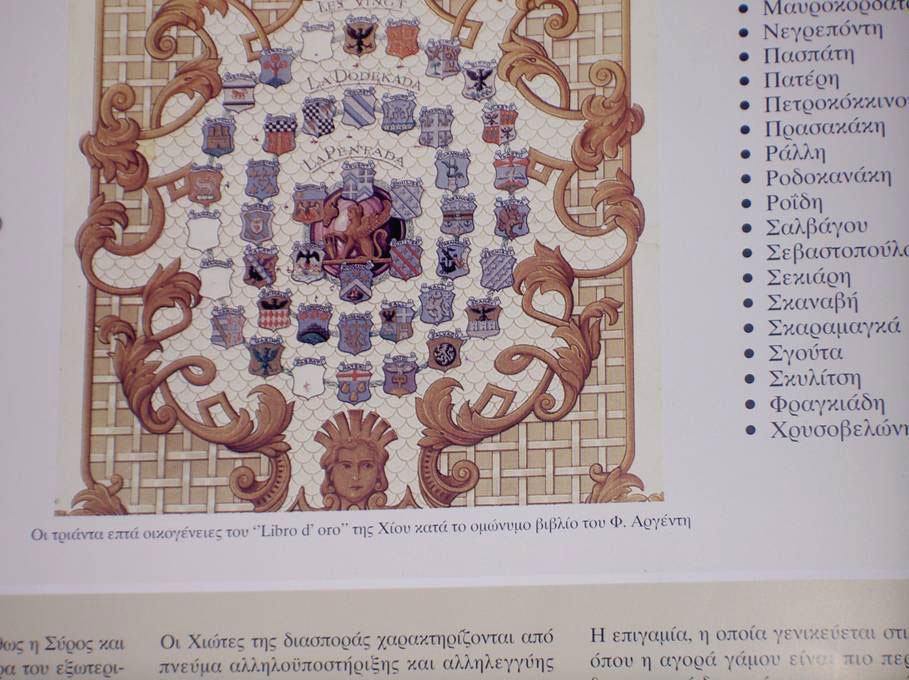

So

the members of these five families, that were at time the most important,

constituted the “Pentada” the supreme executive organ composed by governors,

that were supported by a second order of importance composed by the

representatives of twelve families (Dodecada) and a further consulting

order composed by the other “Les Vingts” (the twenties) families. All

were part of the noble class of Catholic Levantine origin, Greeks added

and mixed with the original Genoese families. With time, all these 37

families families, who were extensive land-owners, were by end of the

XVIIIth century represented in all the levels of local government.

The Castelli family belonged to this ruling elite, and it is possible

that the suffix “Della Vinca”, with which the family were known and

was later recognized in Italy, could have been derived from the ancient

class order of Chios. The system remained unchanged till the annexation

by the Ottoman Empire. Amongst the families which retained important

government charges, were many whose branches were established in Leghorn

by the end of the 18th century: amongst them, the Rodocanacchi,

the Mavrogordato, the Vlasto, the Petrococchino and the Castelli family.

The list of families composing the Chiot Nobility comprises: Agelasto, Argenti, Avierino, Calouta, Calvocoressi, Carali, Casanova, Castelli, Chyssoveloni, Condostavlo, Coressi, Damala, Franghiadi, Galati, Grimaldi, Massimo, Mavrogordato, Negroponte, Paspati, Paterni, Petrococchino, Prassacachi, Ralli, Rodocanachi, Roidi, Salvago, Scanavi, Scaramanga, Schilizzi, Sechiari, Sevastopoulo, Sgouta, Vasto, Vouro, Ziffo, Zizinia, Zygomala. Of these families there are traces of descendence in Leghorn of Argenti, Castelli, Galati, Mavrogordato, Petrococchino, Ralli, Rodocanachi, Roidi, Scanavi, Scaramanga, Schilizzi, Sevastopoulo and Vlasto.

The events of the Greek war of independence binds Chios to Leghorn with the works by Angelica Palli, who wrote the history romance “Alessio or the last days of Psarà” just to finance the fight of his compatriots. To spread the message of this romance, the novel was also written in English and French. Psarà is an island to the north-west of Chios where the last four hundred of the patriots of the Greek insurrection, barricaded themselves, led by Kostantino Kanaris. The fight went against impossible odds, Turks surrounding the island with an impressive number of vessels before their attack. The historical romance of Angelica Palli, published in the same age of the Manzoni “Promessi Sposi”, is based on a love story of a Greek patriot, betrothed to a Chios girl, who falls in love with a Turk that he saves from death during the battle. As in Renzo e Lucia memoirs, a love story across social divides is described within the unfolding stages of a complex historic situation, with social components and doleful events. We don’t know whether Angelica Palli was in Chios during the period, in any case as daughter of the Greek Consul in Leghorn, she was the recipient of the reports of the refugees who escaped there, to the Greek community that existed since the Medici Age. The war happened when the island administration, if not with a Pentada as the established organ of government of the Giustiniani age, was based on five governors of five respective sections of the population where three represented the Greek Orthodox, and two representated the Catholic part of the island. As a result of the work by the Chios researcher, Ioannis Kolakis, through personal documents and textbooks collected in the Chorais Library, it appears that the two governors of the Catholic part were related to the Rodocanacchi family, Pandely Rodocanacchi, who was hanged in Costantinople on the 18th of May 1822, and the other governor being, Domenico Castelli.

The list of families composing the Chiot Nobility comprises: Agelasto, Argenti, Avierino, Calouta, Calvocoressi, Carali, Casanova, Castelli, Chyssoveloni, Condostavlo, Coressi, Damala, Franghiadi, Galati, Grimaldi, Massimo, Mavrogordato, Negroponte, Paspati, Paterni, Petrococchino, Prassacachi, Ralli, Rodocanachi, Roidi, Salvago, Scanavi, Scaramanga, Schilizzi, Sechiari, Sevastopoulo, Sgouta, Vasto, Vouro, Ziffo, Zizinia, Zygomala. Of these families there are traces of descendence in Leghorn of Argenti, Castelli, Galati, Mavrogordato, Petrococchino, Ralli, Rodocanachi, Roidi, Scanavi, Scaramanga, Schilizzi, Sevastopoulo and Vlasto.

The events of the Greek war of independence binds Chios to Leghorn with the works by Angelica Palli, who wrote the history romance “Alessio or the last days of Psarà” just to finance the fight of his compatriots. To spread the message of this romance, the novel was also written in English and French. Psarà is an island to the north-west of Chios where the last four hundred of the patriots of the Greek insurrection, barricaded themselves, led by Kostantino Kanaris. The fight went against impossible odds, Turks surrounding the island with an impressive number of vessels before their attack. The historical romance of Angelica Palli, published in the same age of the Manzoni “Promessi Sposi”, is based on a love story of a Greek patriot, betrothed to a Chios girl, who falls in love with a Turk that he saves from death during the battle. As in Renzo e Lucia memoirs, a love story across social divides is described within the unfolding stages of a complex historic situation, with social components and doleful events. We don’t know whether Angelica Palli was in Chios during the period, in any case as daughter of the Greek Consul in Leghorn, she was the recipient of the reports of the refugees who escaped there, to the Greek community that existed since the Medici Age. The war happened when the island administration, if not with a Pentada as the established organ of government of the Giustiniani age, was based on five governors of five respective sections of the population where three represented the Greek Orthodox, and two representated the Catholic part of the island. As a result of the work by the Chios researcher, Ioannis Kolakis, through personal documents and textbooks collected in the Chorais Library, it appears that the two governors of the Catholic part were related to the Rodocanacchi family, Pandely Rodocanacchi, who was hanged in Costantinople on the 18th of May 1822, and the other governor being, Domenico Castelli.

|

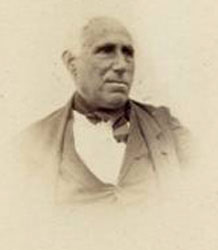

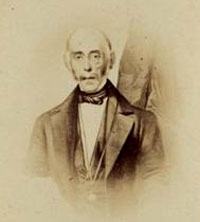

Domenico Castelli

Courtesy of M.me Irene Baldini Orlandini

Courtesy of M.me Irene Baldini Orlandini

2)

The Castelli family

In those sad days of struggle and strife, many members of these powerful families were firstly jailed and then hanged. The pyramidal burial monument, near the municipality building of Chios, recalls the names of 74 members of the noble families of Rodocanacchi, Mavrogordato, Vlastos, cited in long lists. The testament of Domenico Castelli, recently discovered, reveals some important details: jailed inside the Fortress to be hanged, he succeeded through a Capuchin friar to communicate with the Ottoman Sultan and to assert his friendship, attesting to links probably established through his trade. The letter by which he gained his reprieve, seems to be kept in a Paris friary.

In those sad days of struggle and strife, many members of these powerful families were firstly jailed and then hanged. The pyramidal burial monument, near the municipality building of Chios, recalls the names of 74 members of the noble families of Rodocanacchi, Mavrogordato, Vlastos, cited in long lists. The testament of Domenico Castelli, recently discovered, reveals some important details: jailed inside the Fortress to be hanged, he succeeded through a Capuchin friar to communicate with the Ottoman Sultan and to assert his friendship, attesting to links probably established through his trade. The letter by which he gained his reprieve, seems to be kept in a Paris friary.

|

Chios Castle: Door of the Prison at

the center, main access gate of the Castle on the right, Giustiniani

Palace to the left.

|

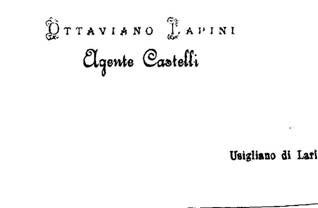

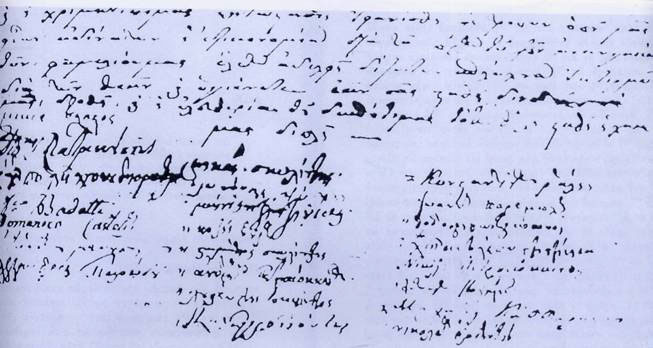

Visiting card of Ottaviano Lapini,

bailiff and agent of the Castelli family, uncle and name-sake of the

cited Mr. Lapini.

To

date the story of Domenico Castelli was revealed through the personal

documents of Ottaviano Lapini living in Usigliano di Lari (Pisa Province,

Italy) whose family was employed by the son Aristide Castelli, cross-referenced

with the genealogical tree of his family furnished by Ugo Castelli della

Vinca, and enriched with evidences kept in the Leghorn Municipality

Historic Archive (CLAS) and from the National Archive of Leghorn.

The Castelli family story in Chios begins in the early 16th century with Giovanni Castelli being established there, arriving from Genoa, about 1520. The name derives from the Castle zone of Genoa, and with this surname they were also linked with the Castello and De Castro families. The succession of the main branches can be traced with the baptisms and marriage certificates of following periods, kept by the Castelli family, with the offspring of Giuseppe and Niccolò (1600), Vincenzo Castelli born in Chios on December the 8th of 1644, Giovanni Castelli who married Catetta Antonii Velasti in 1699, Domenico Castelli born on July the 15th of 1707 who married Lidhinetta Coressi, Francesco Castelli, born on January 27th of 1750 and married Despina Guiducci generating seven children, three males and four females, of whom Domenico (referred above) was the first-born.

The Castelli family story in Chios begins in the early 16th century with Giovanni Castelli being established there, arriving from Genoa, about 1520. The name derives from the Castle zone of Genoa, and with this surname they were also linked with the Castello and De Castro families. The succession of the main branches can be traced with the baptisms and marriage certificates of following periods, kept by the Castelli family, with the offspring of Giuseppe and Niccolò (1600), Vincenzo Castelli born in Chios on December the 8th of 1644, Giovanni Castelli who married Catetta Antonii Velasti in 1699, Domenico Castelli born on July the 15th of 1707 who married Lidhinetta Coressi, Francesco Castelli, born on January 27th of 1750 and married Despina Guiducci generating seven children, three males and four females, of whom Domenico (referred above) was the first-born.

|

Domenico

Castelli was born in Chios on August 1st 1779 but from 1808

he tried to establish himself in Leghorn. There he married Carolina

Maummary Gentil1 from Neuchatel

(Switzerland) on February the 17th of 1808. From their marriage

were born Clementina (18.8.08), Adele (8.2-1810), Ernesta (13.10.1812),

Atenaide (18.12.1815) and Aristide in 1818, all native to Leghorn. The

first commercial attempts were not successful, Leghorn was then recently

a part of the Napoleonic French Empire and some trading rights were

no more allowed, but being obstinate, Castelli was able to turn the

commercial fortunes of his family in the city, steadily from 1814 on.

He succeeded in transfer from the liquidation of his ancestral estates

in Chios and invested his gains derived from trade, not in an ostentious

manner, but by acquiring real estates and interest-bearing securities.

By 1815 Domenico was considered to be the most important trader of Leghorn,

being assigned to be the deputy of the Chamber of Commerce representing

the Greek traders, together with Eustachio Mospignotti.

In Usigliano di Lari he was the second owner of the villa built by the Silvestri family of Leghorn, acquiring also their country properties, enlarging them till they covered about 634,018 square meters. The estate comprised the villa, a farm, several holdings, cultivated lands with vineyards, olive trees, chestnut trees and pasture. From the Lari cadastral maps of 1820, we see the Castelli properties then included several country properties, to which they added the more profitable and less showy holding in Leghorn, thus income generated by the rent of these houses and commercial estates, and furthermore the business activity in insurance and banking.

The ownership by Domenico Castelli of two brigantines [two-masted vessel], such as the “Irene” and “ the “Aristide”, that plied the sea lanes that crossed the Dardanelles and Bosphorus Straits, allowed him to continue the trade with Costantinople and the commerce of the Ukraine wheat. When Domenico Castelli was charged with important government duties in Chios, this involved a shuttle between Leghorn and the eastern Mediterranean. Domenico retained a low profile of his activities, such as, when the Leghorn Governor in 1831, answering to the Siena Governor asking information on the Castelli family, in reply to the request, wrote that his son Aristide, attending Tolomei College of Siena, affirmed that “Domenico Castelli was a Greek man native of Smyrna, living in a place called Scio, and for this reason he had the advantage of being a Catholic. After he established himself in Leghorn, without a fortune and his initial attempts in commerce failed. After an absence of few years he was back around the 1814 and from that period he bought a house with a garden in the town neighbourhood and an extensive farm a short distance away. He is still active in commerce, as we know. As the ways by which he had made such a fast fortune, we suppose they weren’t honourable. By the part of his wife he doesn’t have a pedigree, but he became father of several daughters, one of these married to the Lucca trader Giannini, and a male son whose education he has shown his care. I don’t know if he retains titles or what they are. Recently he mailed a petition to be admitted to the Leghorn Nobility; I don’t care to give any importance to it and sent it back as not approved. He is established with his family in a property near Leghorn” (From the Leghorn Governor Copialettere, October the 31st 1831). The property to which the information referred to, is probably a farm in Salviano, property of the Grifoni family “which was a charitable institution of the Friars of the Calci Certosa” whose name was the Grancia. From here they sent food to the Certosa of the Gorgona Island by means of a boat, the vessel the Castellis were partly owners.

1. Carolina wife of Domenico, was registered as Gentil Maummary from Neuchatel. She was born in Leghorn (Ugo Castelli della Vinca has her baptism certificate). Gentil was a very noble family of French origin, Maummary was a mystery name. Recently, at Baldini Orlandini House in Capannoli, we examined a protrarit of her and we found Montmarie noted as her surname. I think this is the real surname, because I found on the Internet “Montmarie from Neuchatel”, the surname of a Napoleon Army General and a noble family from Switzerland. Her family may well have been part of the international mix of political exiles in this city, at a time of strife across Europe.

In Usigliano di Lari he was the second owner of the villa built by the Silvestri family of Leghorn, acquiring also their country properties, enlarging them till they covered about 634,018 square meters. The estate comprised the villa, a farm, several holdings, cultivated lands with vineyards, olive trees, chestnut trees and pasture. From the Lari cadastral maps of 1820, we see the Castelli properties then included several country properties, to which they added the more profitable and less showy holding in Leghorn, thus income generated by the rent of these houses and commercial estates, and furthermore the business activity in insurance and banking.

The ownership by Domenico Castelli of two brigantines [two-masted vessel], such as the “Irene” and “ the “Aristide”, that plied the sea lanes that crossed the Dardanelles and Bosphorus Straits, allowed him to continue the trade with Costantinople and the commerce of the Ukraine wheat. When Domenico Castelli was charged with important government duties in Chios, this involved a shuttle between Leghorn and the eastern Mediterranean. Domenico retained a low profile of his activities, such as, when the Leghorn Governor in 1831, answering to the Siena Governor asking information on the Castelli family, in reply to the request, wrote that his son Aristide, attending Tolomei College of Siena, affirmed that “Domenico Castelli was a Greek man native of Smyrna, living in a place called Scio, and for this reason he had the advantage of being a Catholic. After he established himself in Leghorn, without a fortune and his initial attempts in commerce failed. After an absence of few years he was back around the 1814 and from that period he bought a house with a garden in the town neighbourhood and an extensive farm a short distance away. He is still active in commerce, as we know. As the ways by which he had made such a fast fortune, we suppose they weren’t honourable. By the part of his wife he doesn’t have a pedigree, but he became father of several daughters, one of these married to the Lucca trader Giannini, and a male son whose education he has shown his care. I don’t know if he retains titles or what they are. Recently he mailed a petition to be admitted to the Leghorn Nobility; I don’t care to give any importance to it and sent it back as not approved. He is established with his family in a property near Leghorn” (From the Leghorn Governor Copialettere, October the 31st 1831). The property to which the information referred to, is probably a farm in Salviano, property of the Grifoni family “which was a charitable institution of the Friars of the Calci Certosa” whose name was the Grancia. From here they sent food to the Certosa of the Gorgona Island by means of a boat, the vessel the Castellis were partly owners.

1. Carolina wife of Domenico, was registered as Gentil Maummary from Neuchatel. She was born in Leghorn (Ugo Castelli della Vinca has her baptism certificate). Gentil was a very noble family of French origin, Maummary was a mystery name. Recently, at Baldini Orlandini House in Capannoli, we examined a protrarit of her and we found Montmarie noted as her surname. I think this is the real surname, because I found on the Internet “Montmarie from Neuchatel”, the surname of a Napoleon Army General and a noble family from Switzerland. Her family may well have been part of the international mix of political exiles in this city, at a time of strife across Europe.

|

Francesco Giustiniani

Courtesy by M.me Irene Baldini Orlandini

Courtesy by M.me Irene Baldini Orlandini

|

Michele Castelli (1795-1860), brother

of Domenico

|

Carolina Maummary Gentil Castelli

In

respect to Chios, after escaping the hanging, we don’t know if he ever

returned there; but it is probable that the trade contacts with the

Ottoman Empire continued, while the family tried to enforce one’s position

in Tuscany. Surely, some of the families that escaped from Chios were

helped by Castellis: apart Reggio and Guiducci family with whom there

were frequent family ties (the sister Apollonia married Giovanni Reggio,

his brother Michele married Aspasia Guiducci, Domenico’s mother was

Aspasia Guiducci daughter of Maria Reggio), the Rodocanachi, the Mavrogordato,

the Papudoff and the Giustiniani families who escaped to Tuscany, had

probably an important support from Domenico Castelli, who was well established

in Leghorn with his commercial activity. Established in Leghorn, as

was the habit in the Levantine community, the family ties were re-inforced

by recurrent marriages with families of the same origin: for example

Rodocanachi with Calvocoressi, Vlasto, Ralli, Scaramanga, Papoudoff

and Sechiari. Also the Giustiniani family had family ties with Castelli

family, so then Domenico’s sister, Marietta (Minuchò) married

Vincenzo Giustiniani in Chios and on that island was born their two

sons, Francesco (15.12.1815) and Giovan Battista (1818) who escaped

to Leghorn. Domenico Castelli’s daughters strengthened, with their marriages,

the position of the family in Tuscany aristocracy. Clementina married

Giovan Battista Cantini, nobleman from Pistoia, Adele married the rich

Lucca trader Tommaso Giannini, Ernesta married Alessandro Malenchini,

Irene married the Pisa noble man Tommaso Tommaso Orlandini, Atenaide

married the Earl Niccolò Niccolai Gamba.

The Castelli family was inscribed in the Golden Book of Leghorn Aristocracy between the 1833 and the 1836, with Bartolomei, Borgheri, Grant, Malenchini, Ricci, Rodocanachi and Stub families. This Leghorn merchant aristocracy was somewhat international in nature with John Grant being a Protestant from Edinburgh, Scotland and the Stub family originating from Bergen in Norway. The trading activities abroad, now suggested the Castellis to have “opened courses” towards England where the Castelli and Giustiniani and Co. registered in London, composed by Francesco and Giovanbattista Giustiniani, Michele Reggio, Michele Castelli and Domenico Castelli, a firm in activity till the year 1851, when it was declared insolvent. Domenico died in Leghorn on March the 8th 1850 and a his death certificate was issued by the Santa Caterina Church parish priest in Leghorn, and was exhibited as evidence at the debate of the bankrupcy judgement prompted by the Clarke Company of Zante (one of the British administered Ionian islands). At the time of his death, Domenico was living in the villa built by them in 1834 in Castelli street, in the Pontino quarter on Gentil property, that is on his wife’s property, which still bears the shield on the façade, and where in the atrium there was a bust of his wife with an inscription, as referred in Piombanti’s Leghorn Guide. The burial of Domenico in the Montenero House of Fame and his monument suggest some observations: the chapel is dedicated to “Carolina Castelli and her family”: in the class of the families chapels she is the only woman sited as a symbol. Furthermore the wife is celebrated by a monument and an engraved stone centrally placed in the centre of the chapel.

On the ground floor there are the mortal remains of Domenico, his mother Despina Guiducci Castelli, the graves of Aristide and of the child Tommaso Orlandini who died 3 years of age, while in the left corner, with an engraved stone in view only from the inside of the chapel, there was the Domenico Castelli monument. Carolina Maummary Gentil Castelli died on the 5th of September in 1863, 13 years after her husband. It was probably he was her son, Aristide who designed the way to celebrate his parents memory in the chapel and to prepare the graves for other relatives. We don’t know if the motive for this mortuary was the Aristide’s devotion for his mother or the preserve the legacy of the estate or respect the privacy of his father’s operations to suggest this disposition.

On the monument of the Castelli della Vinca and Reggio families, an inscription recalls the memory of Federico Braggiotti, who died in 1860, whose remains were placed near the grave stone of Michele Castelli, who was like a godson to him (to be confirmed). Castelli died three months after the Federico’s death because he didn’t survive the pain of the mourning.

The Castelli family was inscribed in the Golden Book of Leghorn Aristocracy between the 1833 and the 1836, with Bartolomei, Borgheri, Grant, Malenchini, Ricci, Rodocanachi and Stub families. This Leghorn merchant aristocracy was somewhat international in nature with John Grant being a Protestant from Edinburgh, Scotland and the Stub family originating from Bergen in Norway. The trading activities abroad, now suggested the Castellis to have “opened courses” towards England where the Castelli and Giustiniani and Co. registered in London, composed by Francesco and Giovanbattista Giustiniani, Michele Reggio, Michele Castelli and Domenico Castelli, a firm in activity till the year 1851, when it was declared insolvent. Domenico died in Leghorn on March the 8th 1850 and a his death certificate was issued by the Santa Caterina Church parish priest in Leghorn, and was exhibited as evidence at the debate of the bankrupcy judgement prompted by the Clarke Company of Zante (one of the British administered Ionian islands). At the time of his death, Domenico was living in the villa built by them in 1834 in Castelli street, in the Pontino quarter on Gentil property, that is on his wife’s property, which still bears the shield on the façade, and where in the atrium there was a bust of his wife with an inscription, as referred in Piombanti’s Leghorn Guide. The burial of Domenico in the Montenero House of Fame and his monument suggest some observations: the chapel is dedicated to “Carolina Castelli and her family”: in the class of the families chapels she is the only woman sited as a symbol. Furthermore the wife is celebrated by a monument and an engraved stone centrally placed in the centre of the chapel.

On the ground floor there are the mortal remains of Domenico, his mother Despina Guiducci Castelli, the graves of Aristide and of the child Tommaso Orlandini who died 3 years of age, while in the left corner, with an engraved stone in view only from the inside of the chapel, there was the Domenico Castelli monument. Carolina Maummary Gentil Castelli died on the 5th of September in 1863, 13 years after her husband. It was probably he was her son, Aristide who designed the way to celebrate his parents memory in the chapel and to prepare the graves for other relatives. We don’t know if the motive for this mortuary was the Aristide’s devotion for his mother or the preserve the legacy of the estate or respect the privacy of his father’s operations to suggest this disposition.

On the monument of the Castelli della Vinca and Reggio families, an inscription recalls the memory of Federico Braggiotti, who died in 1860, whose remains were placed near the grave stone of Michele Castelli, who was like a godson to him (to be confirmed). Castelli died three months after the Federico’s death because he didn’t survive the pain of the mourning.

|

Domenico Castelli burial monument at

the Montenero House of Fame (Famedio)

|

The monument for Carolina Castelli

|

and that of Castelli della Vinca and

Reggio.

|

Aristide Castelli

Courtesy of Mr Ottaviano Lapini

Courtesy of Mr Ottaviano Lapini

Aristide

didn’t get married and observing both the prolific sisters descendents

and that of the other Castelli branches, it seems strange that a person

with noticeable economic resources (that included the export of fine

flour to London for biscuit manufacturing) didn’t enlarge one’s family

with proper descendents. In effects the match between the photo portrait

of Domenico, so gruff and sturdy, it is in contrast with the sitting

portrait of Aristide, with a smoothly dark grimace of his face, thin

lower limbs and wide thorax, as to indicate a congenital cardiopathy

or an illness at that time may have had prejudice attached to it, thus

damaging his reputation. Aristide didn’t follow the commercial activity

of his father, which at the beginning of the second half of the 19th

century, was now more centered in banking and finance.

So he remained with his mother and at her death he edited in her memory the prayer book of the Abbot Goffinè which was distributed in Churches and Monasteries, and in his testament he decreed that in the recurrence of the 5th of September, in the towns where he had properties (Usigliano di Lari, Forcoli Palaia, San Jacopo in Acquaviva in Leghorn and Arceno in Castelnuovo Berardenga), the Municipality Secretary would draw some funds for dowries for the local girls who were to be married that year. The proceedings of the Pio Legato [bequest] Castelli, with the rules of allocation, are kept in the Historic Archives of Leghorn Municipality. The drawing of the funds for the dowries and the allocation of legacies act as an alternative census to several civic and religious institutions, many of these in Leghorn and Florene, and this act of charity operated from 1880, the year after Aristide’s death, till 1915 when the funds were collected in a special fund of the orphans of the World War I.

So he remained with his mother and at her death he edited in her memory the prayer book of the Abbot Goffinè which was distributed in Churches and Monasteries, and in his testament he decreed that in the recurrence of the 5th of September, in the towns where he had properties (Usigliano di Lari, Forcoli Palaia, San Jacopo in Acquaviva in Leghorn and Arceno in Castelnuovo Berardenga), the Municipality Secretary would draw some funds for dowries for the local girls who were to be married that year. The proceedings of the Pio Legato [bequest] Castelli, with the rules of allocation, are kept in the Historic Archives of Leghorn Municipality. The drawing of the funds for the dowries and the allocation of legacies act as an alternative census to several civic and religious institutions, many of these in Leghorn and Florene, and this act of charity operated from 1880, the year after Aristide’s death, till 1915 when the funds were collected in a special fund of the orphans of the World War I.

|

Photo courtesy of Mr. Ottaviano Lapini.

|

|

|

The shield of Castelli family

with a draw bridge between two towers, may be to testify their

departure from Chios, over the first floor terrace of the Castelli

palace. |

The monument in Montereno house,

on the opposite site of the court, to the Christian Maronite family

of Ghantuz Cubbe from Aleppo, which were in Leghorn as a powerful

trading family and bishops, another sign of the diversity of the

community. |

||

Mavrogordato Palace, attesting

to the power of these and other (Reggio also have a palace in

Leghorn) Greek families. This former residence is today the main site of ENEL General Electric Works of Italy in Leghorn. |

|||

Notes: 1- Dr. Antonio Cambi is the president of the Rondine Association, based in Usigliano di Lari, Tuscany Italy. This association aims to celebrate the cultural legacy and historical links of the region, enhance cultural contacts and issues regular bulletins to inform its membership of developing projects and upcoming cultural events. The association is also actively pursuing contacts with Chios (and elsewhere in the Mediterranean) with the aim of developing further knowledge of historical links to the island. To contact the association: info[at]rondinet.it

2- Mr Cambi’s investigation in to the roots of the Castelli family is on-going, and in the future he plans to add to the above submission with information concerning other branches (if they are related, complicated by the fact that there are differing suffixes) of this ancient family whose domecile stretched from London, Algeria to Constantinople etc. Work is progressing on a wider family tree built through contributions, however the surname can generate a confusion as at times Castellis married other Castellis sometimes cousins and sometimes seemingly unrelated. A sister of Domenico and Michele Castelli (They were three brothers, with Giovanni, and four sisters), married a Castelli from London, a cousin while another sister married an unconnected Castelli. In Feb 2006 he submitted a family connection tree prepared with the assistance of Ugo Castelli della Vinca, displaying Carolina Maummary and her relationship to families such as Reggio, Castelli, Guiducci, Tubini, Glavany, although details of the ‘Braggiotti pupils’ are still being worked out - download excel file here:

3- Leghorn was akin to Smyrna of the West during more than two centuries, a vibrant port attracting a polyglot population that prospered with the city, its history examined further in this on-line article published in the University of Nice’s web site, a private site and the book examining the history of the Mediterranean basin (The Mediterranean in History - edited by David Abulafia) and in a section comparing the port cities of Smyrna and Livorno.

4- A book Mr Cambi highly recommends for the merchant history of the Leghorn area is book by David LoRomer, a modern history teacher of the Michigan University, who wrote “Merchants and Refrom in Livorno (1814-1868)” for the University of Califronia Press.

5- Another study Mr Cambi rates highly is by Despina Vlami - “Commerce and identity in the Greek communities: Livorno in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries”, which highlights close connections between Chios and Leghorn in the field of education:

“The Greek Brotherood in Leghorn founded a school in 1806 with Greek teachers for their community, with the supervision of the merchant Mihail Zosimas. In 1822 the Greek School was attended by 42 students, divided in to three classes, where they learnt ancient Greek (language and literature), ethics, history and religious instruction. The teachers were following a program based on the model of the Chios School of Philosophy. This was one of the most important educational institutions operating in Ottoman times on the island of Chios, and maintained a close relationship with the Brotherhood in Livorno (P. Zerlendis “The Greek School in Livorno 1805-1837” Parnassos, 1889 pp. 324-5 in Greek). This institution was in economic trouble between 1822 and 1826, providing major contributions for the Greek Revolution. The Brotherhood also financed three students to support their university course: one from Peloponnese, one from Epirus, and one from Chios or Smyrna. They must possess intellectual qualities, aged between 20 and 25 years, come from family with poor means, have a good knowledge of the Greek language and grammar, and be interested to study any modern discipline except medicine. The selected were addressed to Pisa and Florence Universities. The Chian origin merchants in Leghorn warmly supported this school, and published school texts that they sent to Greece. There is a letter of Fragulis Rodokanakis dated 1811, thanking for the books sent to Chios from Leghorn. These books were also sold in Smyrna by the commercial house of D. Rodokanakis & Co.”

Soon the Greek Consul of Leghorn, Professor Giangiacomo Panessa, will edit a translation of Professor Vlami’s book on the Greek families of Leghorn.

6- Other books of relevance to this study are:

‘Merchants, Interlopers, Seamen and Corsairs: the “Flemish” community in Livorno and Genoa (1615 - 1635) - Marie-Christine Engels’

‘Merchanti Inglesi a Livorno 1573-1737; Alle origini di una ‘British Factory’ – Michela D’Angelo - Instituto di studi storici – 2004’

‘The British Factory in Livorno – H.A. Hayward’, etc.

7- Right in the heart of the downtown commercial quarter of Izmir (Smyrna), within the Kemeraltı district there is a Kestelli Çarşısı [bazaar] as well as the same name being attached to a street and building in the area, and it is highly likely the name is a corruption of the name Castelli, a legacy of this family presence in times past.