In this article I would like to look at the history of Turkey between 1907 and 1929, a very turbulent period, through the eyes of a Levantine company based in Smyrna.

Since the times of Byzantium the Europeans in Constantinople and Smyrna had lived in a commercial paradise. Benefiting from the ‘capitulations’ of the treaties with the Byzantines and then the Ottomans, the Europeans were subject to their own national laws, which were administered by their own consuls, and they paid practically no tax. Smyrna, with its large natural harbour and fertile hinterland, was a prosperous centre of export trade in dried fruit, tobacco and carpets.

The principal carpet exporters at the beginning of the twentieth century were the Spartali family. They were originally Armenian, but the firm was now run by the Italian Aliotti family, who had married into them. They employed thousands of weavers all over central and eastern Anatolia. Another family in the trade was that of De Andria, also Italian, who had been in Turkey for centuries. There were two English families in the carpet business – the La Fontaines (who were originally French) and the Bakers.

Lafontaine’s particular expertise was design and dyeing. The first Baker in Turkey had come to work as a garden designer for the Sultan in 1847, where he had prospered and seen the potential of the carpet trade [further info]. There were Turkish exporters, of course, particularly the famous Çolakzadeh family, but they worked on a much smaller scale.

In 1907 the competition between these Levantine families for weavers and raw material became so intense that they decided to amalgamate and form a cartel, The Oriental Carpet Manufacturers, known as the OCM, which they registered in Smyrna as an English company, under English law.

To this cartel was added the English Sykes company, which owned a wool mill at Bandirma producing yarn and cloth.

Next to be recruited to the company was the American adventurer Charles B. Fritz. Fritz was by chance in Constantinople in the final years of Sultan Abdul Hamid, when the lives of high government officials were often in danger. One of the vezirs had fallen foul of the Sultan, and was trying to escape to Italy. Fritz was also about to sail for Italy, on a passport which included his wife, although she was not travelling with him.

When an attaché at the British embassy heard of this, he persuaded Fritz to let the vezir, disguised in a Muslim woman’s veil, board the ship to Naples as his wife, and the man was saved. Some years later the minister regained his position. Fritz approached him, and the grateful minister granted Fritz the monopoly for the entire Anatolian wool clip.

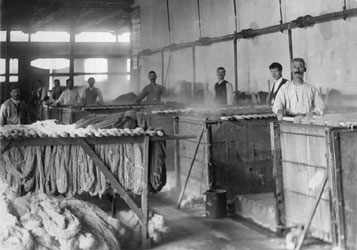

The cartel now had the wool, the spinning mills, the dye works and sales outlets all over Europe and the United States. By the end of the two years following its foundation in January 1908 it was employing 100,000 weavers working on 20,000 looms in 27 towns and cities all over Turkey, with some 90% of all Turkish production in its hands. Its profits were phenomenal and international bankers were falling over each other in order to lend money to them.

However, it had not been an easy start. In January 1908, a hundred years ago, a number of banks in the United States collapsed, and the American stock market lost half of its value. This paralyzed trade over much of the world for four months and had a particularly bad effect on the demand for luxury goods such as carpets. It was as a result of this banking crisis a hundred years ago that the Federal Reserve Bank was established, to ensure that it should never happen again!

1908, the year of the establishment of the company, also saw the beginning of the constitutional revolution in Turkey and the rise of the Young Turks. In July the Young Turks of Salonika, which was then still part of the Ottoman Empire, sent a telegram to the sultan demanding a new constitution. The newspapers of the next day startled the public with the use of previously unseen words such as ‘freedom’, ‘nation’ and ‘parliament’. The atmosphere was like that in Moscow on the night of Gorbachev’s speech on glasnost and perestroika.

The new constitution led to a period of both social and economic liberalism, and educated women began to appear unveiled in public.

At the same time, the Ottomans suffered the losses of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria and Crete, all in the same year. Also in the same year there were the first-ever strikes among workers in the coal mines, the railways and in the new factories. These disasters led many Turks to call for the abandonment of the new liberalism and a return to the old certainties – in this case, of Islamic law and the hijab.

A particularly famous incident was the rioting by the women of Uşak, the principal carpet weaving town of Turkey, who smashed the new industrial wool spinning mills. These had been built because the annual production of carpets in Uşak had increased in the previous ten years from 75,000 square metres to 250,000 square metres and the hand spinners could not keep up with the increased demand for yarn. The new mills, of course, took work away from these poor women, who depended for their livelihoods on spinning yarn at home for the carpet trade.

In March 1909 the modernising Turkish army decided to remove the Sultan and send him into exile. Since the new constitution had provided no formula for deposing a sultan, the reformers found that the only way to legitimise their act was to persuade the Sheikh ul-Islam to issue a suitable Islamic fatwa.

The Ottoman Empire at this time was still a cosmopolitan state, whose citizens included sizeable numbers of Christian Greeks and Armenians, Jews and Balkan people, not to mention the Arabs of Syria and Mesopotamia. Generally speaking, the minorities enjoyed civic rights and were protected.

The OCM, as it expanded its weaving further and further into Anatolia, employed, almost without exception, Greek or Armenian weavers. Two years ago some students in Izmir asked me whether this was because the Frankish owners of the company were prejudiced against Muslims. ‘Far from it;’ I replied, ‘on the contrary, they considered Turkish weavers to be better. The problem was that the Muslims would not allow the company inspectors to enter their houses to check the work on the looms.’ Since the OCM had given the weavers the wool and had paid them an advance to start work, they had to insist on inspecting the quality. There was no solution other than to employ Christian weavers, who had no such prejudices. One of the students then asked me why the OCM could not use female inspectors. My answer to this was to ask him if he thought that any family, Muslim or Christian, would have allowed their women to travel, alone, for days on end, to remote villages in central Anatolia to visit the houses of strangers to look at carpets. I think you can guess what his answer was.

From now on the story is dominated by wars. In 1911 Italy occupied what is now Libya, then Ottoman territory, and also Rhodes. The Italian fleet blockaded the Dardanelles, cutting Constantinople off from Europe. The banks, fearing the worst, closed their doors, cutting off credit. Carpet orders were cancelled and the poor weavers in deepest Anatolia, who had never heard of Italy or Rhodes, found themselves out of work.

The chief Italian negotiator at the Treaty of Lausanne, which settled the dispute between Italy and Turkey, was one Oscar Missir, a close relation of the De Andria family of Smyrna.

More war followed in 1912 and 1913, this time in the Balkans. Turkey lost Salonika to Greece and Bulgaria occupied Edirne. Constantinople was filled with Muslim refugees from the Balkans and northern Greece, who brought with them typhus and cholera, which began to spread in the city. People were afraid to leave their houses. The normally busy shopping streets of Constantinople were deserted. Tourists stopped coming and this lucrative market for OCM’s carpets dried up.

One hundred thousand refugees came to Smyrna from Constantinople, bringing their diseases with them. The markets in Europe, nervous at the possible outcome of these wars to the east, slowed down, but the American market, where the OCM had had the foresight to establish itself, held up well and went on to grow fast.

The usual picture of the First World War is one of slaughter in the mud and trenches in France and Belgium. For the Levantines in Turkey it was rather different. The German propaganda machine played on the resentment of the nationalist Young Turks, led by Enver Pasha, against the privileged Europeans and Levantines, who profited from the capitulations and controlled the state revenues, most of which went to service the Ottoman national debt to the European banks. Kaiser Wilhelm was looking for a way to open the gates for Germany towards India. Hoping to exploit the power of religion in the Middle East and beyond, he announced to the Islamic world that he had become a Muslim and that, with the Ottoman Caliph beside him, he would protect all Muslims against the British. You all know the result of that.

In October 1914 the Ottoman government unilaterally abolished the capitulations. The OCM company therefore had to register itself as a Turkish company, which meant that it now depended on the Turkish government rather than the British government for protection. In November Turkey and Britain were at war. What now should be the position of the OCM and its European owners? The question of loyalty that faced the directors was difficult, similar to that of the Anglo-Argentines during the Falklands war.

The wool mills had for years been providing cloth to the Ottoman army for uniforms. Now the Ottoman government threatened to sequestrate the mills unless they continued to supply this material to them. The owners of the OCM, although technically British, French or Italian citizens, had lived in Turkey for hundreds of years and were treated by the British government as if they were Ottoman citizens. Should they resist Ottoman demands, or collaborate?

In the end, they decided that firstly, as the war was sure to be a short one, they should keep hold of the company so that they could resume business afterwards and that, secondly, supplying cloth for uniforms would make little difference to the outcome of the war. In any case, even if they refused to collaborate, the Ottomans would surely confiscate the company and still get their cloth. So, they collaborated.

There now enters on the scene the remarkable Ottoman governor of Smyrna, Evrenoszadeh Rahmi Bey, whose statue still stands in Izmir. This man came from an old landowning family of Salonika and was one of the original modernising Young Turks. While in the rest of Turkey the authorities imprisoned or exiled all Europeans of hostile nations to the interior, Rahmi Bey gave the Europeans of Smyrna twelve days to leave, if they wished. If they wished to stay, he promised, he would protect them. And, indeed, he did protect them. Not only did he ensure that the Ottoman government paid for the cloth they received from the OCM, he also allowed the Europeans to keep their guns and to go hunting with them whenever and wherever they wished, even giving them an escort to make sure that nobody troubled them.

Occasionally Rahmi Bey came under pressure from Enver Pasha and his pro-German party and was obliged to demonstrate his patriotism by locking up some Levantines for a few days, but he treated them always with the greatest courtesy. From the beginning he had been opposed to the war, foreseeing the disaster that was to befall Turkey at the end of it. In spite of that, at the end of the war the Allies imprisoned him and exiled him to Malta, as being of the war party, and it took a lot of effort from the Levantine families to have him released. After the signing of the peace, as a reward, the company made him a director.

After the war the OCM found itself with huge stocks of carpets which, for lack of shipping, they had been unable to move. They were thus able to profit from the backlog of demand in the USA and in the victorious countries of Europe, which had been starved of imports all this time. The economies of Germany and Austro-Hungary, however, which had previously been very good markets, were now destroyed. However, the company now had a problem in Turkey with production, in that the company had lost many of its Armenian weavers during the events of 1915 and 1916.

The end of war did not bring peace to Turkey. In May 1919 a Greek army landed in Smyrna and quickly advanced far into Anatolia. Their advance was accompanied by much destruction, particularly of the carpet weaving town of Ghiordes [Gördes], which was destroyed in 1921. Anatolian carpet production practically came to a halt.

In the spring of 1922 Mustafa Kemal’s army pushed the Greeks steadily west. The retreating Greek army set fire to everything before it. On 9th September the Turkish army entered Smyrna. Four days later the city caught fire. It burned from 13th-16th September and much of Smyrna was destroyed. Some two thousand lives were lost. There is still, even today, much argument as to who was responsible, each side blaming the other and both blaming the Armenians.

There were dreadful scenes at the harbour. The Allied naval vessels in the bay looked on as Greeks and Armenians, pushed by the crowds behind, plunged into the sea to escape the flames. The OCM head office on the quay was burned and its entire stock of carpets was lost. The American Tobacco Company also lost its entire stock of tobacco. A curious story about the fire is that all the paper money in the banks was burned, as were the stocks of paper. This meant that for some time new bank notes had to be printed on very small pieces of paper.

These colossal losses became the subject of insurance claims into which politics entered in a big way. In brief, the goods had not been insured against war risk, since the owners had seen no risk of war. The Americans therefore were anxious not to blame the Turkish army for the fire. The British, for their part, were interested in the oilfields of Mosul and also had no wish to antagonise the new Turkish government. The record is therefore murky.

The companies claimed against the insurance companies for accidental damage, which they refused. A test court case in 1923 found in favour of the insurance companies, in other words, that the fire was an act of war and not an accident. This wiped £100,000 sterling off the OCM books, equivalent to about US$ 8m today. This decision, did however, later enable the companies to claim damages for their losses from the Turkish government by way of war reparations.

But these are small matters in comparison to what followed. The collapse of the Ottoman empire after the Great War, followed by the victory of the new Turkish army under Ataturk, led to the founding of the new Turkish republic. There followed the great population exchanges in 1924, but – what was the effect of this upheaval on the carpet company?

In the post-war years the OCM found that it had now lost all its weavers in Turkey. The Armenians had gone in 1915, and now they had lost the Greek weavers. The only solution was to establish looms in Athens and on Rhodes. Rhodes, being still under Italian occupation, supplied the Italian market free of customs duty and did well for a while. In Turkey the taxes on trade imposed by the new republic, as well as the threat of trouble coming from Bolshevik Russia, drove the traders of Persian and Caucasian carpets in Constantinople to the safety of London, where their businesses thrived in the bonded warehouses that were given to them beside the docks.

When the European governments imposed protective trade tariffs, by way of imperial preference, Indian carpets were imported into England and Algerian carpets were imported into France almost duty free, to the great detriment of the Turkish trade, which was obstructed by heavy import duties in both countries. The once thriving Turkish carpet industry, employing many tens of thousands of spinners, dyers and weavers, was destroyed by war, politics, taxes and political instability.

In 1928 the Turkish government changed its attitude towards commerce and relaxed its tax regime, which led to a brief and spectacular boom in business which, but for the Wall Street crash of 1929, might have continued. Çolakzadeh, the only Turkish substantial carpet exporter who had survived independently of the OCM, was clever enough to see it coming and was able to sell his stocks in New York just in time before their value evaporated. Once again, the illiterate weavers in the villages of Turkey, and also Iran, found themselves out of work as a consequence of follies committed by educated people of whom they had never heard.

This has been a patchwork of a story. I have outlined it here for you in the hope that you might consider the history of this company and the times that it lived in, and ask yourselves some questions: some questions about nationality, sovereignty, the necessity for maintaining conditions favourable for trade and industry, the need at the same time for control of banks and commercial institutions, and the need for economic and political stability, without sclerosis. Today we are all faced with these questions, but we are not the first to have faced them. Many of today’s problems faced us a hundred years ago. If we can reflect on the mistakes that were made then, perhaps we can come up with some better solutions now.

Notes: 1- Antony Wynn is the author of the ‘Three Camels to Smyrna: Times of War and Peace in Turkey, Persia, India, Afghanistan & Nepal 1907-1986, The Story of the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers Company’- 288 pages, 2008 - segment

2- To read the interview conducted post Antony Wynn’s talk in 2012, click here:

Antony Wynn giving a lecture to members of the Anglo-Turkish Society on the subject of his book, post publication, January 2012

Since the times of Byzantium the Europeans in Constantinople and Smyrna had lived in a commercial paradise. Benefiting from the ‘capitulations’ of the treaties with the Byzantines and then the Ottomans, the Europeans were subject to their own national laws, which were administered by their own consuls, and they paid practically no tax. Smyrna, with its large natural harbour and fertile hinterland, was a prosperous centre of export trade in dried fruit, tobacco and carpets.

The principal carpet exporters at the beginning of the twentieth century were the Spartali family. They were originally Armenian, but the firm was now run by the Italian Aliotti family, who had married into them. They employed thousands of weavers all over central and eastern Anatolia. Another family in the trade was that of De Andria, also Italian, who had been in Turkey for centuries. There were two English families in the carpet business – the La Fontaines (who were originally French) and the Bakers.

Lafontaine’s particular expertise was design and dyeing. The first Baker in Turkey had come to work as a garden designer for the Sultan in 1847, where he had prospered and seen the potential of the carpet trade [further info]. There were Turkish exporters, of course, particularly the famous Çolakzadeh family, but they worked on a much smaller scale.

In 1907 the competition between these Levantine families for weavers and raw material became so intense that they decided to amalgamate and form a cartel, The Oriental Carpet Manufacturers, known as the OCM, which they registered in Smyrna as an English company, under English law.

|

|

|

To this cartel was added the English Sykes company, which owned a wool mill at Bandirma producing yarn and cloth.

Next to be recruited to the company was the American adventurer Charles B. Fritz. Fritz was by chance in Constantinople in the final years of Sultan Abdul Hamid, when the lives of high government officials were often in danger. One of the vezirs had fallen foul of the Sultan, and was trying to escape to Italy. Fritz was also about to sail for Italy, on a passport which included his wife, although she was not travelling with him.

When an attaché at the British embassy heard of this, he persuaded Fritz to let the vezir, disguised in a Muslim woman’s veil, board the ship to Naples as his wife, and the man was saved. Some years later the minister regained his position. Fritz approached him, and the grateful minister granted Fritz the monopoly for the entire Anatolian wool clip.

The cartel now had the wool, the spinning mills, the dye works and sales outlets all over Europe and the United States. By the end of the two years following its foundation in January 1908 it was employing 100,000 weavers working on 20,000 looms in 27 towns and cities all over Turkey, with some 90% of all Turkish production in its hands. Its profits were phenomenal and international bankers were falling over each other in order to lend money to them.

However, it had not been an easy start. In January 1908, a hundred years ago, a number of banks in the United States collapsed, and the American stock market lost half of its value. This paralyzed trade over much of the world for four months and had a particularly bad effect on the demand for luxury goods such as carpets. It was as a result of this banking crisis a hundred years ago that the Federal Reserve Bank was established, to ensure that it should never happen again!

1908, the year of the establishment of the company, also saw the beginning of the constitutional revolution in Turkey and the rise of the Young Turks. In July the Young Turks of Salonika, which was then still part of the Ottoman Empire, sent a telegram to the sultan demanding a new constitution. The newspapers of the next day startled the public with the use of previously unseen words such as ‘freedom’, ‘nation’ and ‘parliament’. The atmosphere was like that in Moscow on the night of Gorbachev’s speech on glasnost and perestroika.

The new constitution led to a period of both social and economic liberalism, and educated women began to appear unveiled in public.

At the same time, the Ottomans suffered the losses of Bosnia-Herzegovina, Bulgaria and Crete, all in the same year. Also in the same year there were the first-ever strikes among workers in the coal mines, the railways and in the new factories. These disasters led many Turks to call for the abandonment of the new liberalism and a return to the old certainties – in this case, of Islamic law and the hijab.

A particularly famous incident was the rioting by the women of Uşak, the principal carpet weaving town of Turkey, who smashed the new industrial wool spinning mills. These had been built because the annual production of carpets in Uşak had increased in the previous ten years from 75,000 square metres to 250,000 square metres and the hand spinners could not keep up with the increased demand for yarn. The new mills, of course, took work away from these poor women, who depended for their livelihoods on spinning yarn at home for the carpet trade.

In March 1909 the modernising Turkish army decided to remove the Sultan and send him into exile. Since the new constitution had provided no formula for deposing a sultan, the reformers found that the only way to legitimise their act was to persuade the Sheikh ul-Islam to issue a suitable Islamic fatwa.

The Ottoman Empire at this time was still a cosmopolitan state, whose citizens included sizeable numbers of Christian Greeks and Armenians, Jews and Balkan people, not to mention the Arabs of Syria and Mesopotamia. Generally speaking, the minorities enjoyed civic rights and were protected.

The OCM, as it expanded its weaving further and further into Anatolia, employed, almost without exception, Greek or Armenian weavers. Two years ago some students in Izmir asked me whether this was because the Frankish owners of the company were prejudiced against Muslims. ‘Far from it;’ I replied, ‘on the contrary, they considered Turkish weavers to be better. The problem was that the Muslims would not allow the company inspectors to enter their houses to check the work on the looms.’ Since the OCM had given the weavers the wool and had paid them an advance to start work, they had to insist on inspecting the quality. There was no solution other than to employ Christian weavers, who had no such prejudices. One of the students then asked me why the OCM could not use female inspectors. My answer to this was to ask him if he thought that any family, Muslim or Christian, would have allowed their women to travel, alone, for days on end, to remote villages in central Anatolia to visit the houses of strangers to look at carpets. I think you can guess what his answer was.

From now on the story is dominated by wars. In 1911 Italy occupied what is now Libya, then Ottoman territory, and also Rhodes. The Italian fleet blockaded the Dardanelles, cutting Constantinople off from Europe. The banks, fearing the worst, closed their doors, cutting off credit. Carpet orders were cancelled and the poor weavers in deepest Anatolia, who had never heard of Italy or Rhodes, found themselves out of work.

The chief Italian negotiator at the Treaty of Lausanne, which settled the dispute between Italy and Turkey, was one Oscar Missir, a close relation of the De Andria family of Smyrna.

More war followed in 1912 and 1913, this time in the Balkans. Turkey lost Salonika to Greece and Bulgaria occupied Edirne. Constantinople was filled with Muslim refugees from the Balkans and northern Greece, who brought with them typhus and cholera, which began to spread in the city. People were afraid to leave their houses. The normally busy shopping streets of Constantinople were deserted. Tourists stopped coming and this lucrative market for OCM’s carpets dried up.

|

|

|

One hundred thousand refugees came to Smyrna from Constantinople, bringing their diseases with them. The markets in Europe, nervous at the possible outcome of these wars to the east, slowed down, but the American market, where the OCM had had the foresight to establish itself, held up well and went on to grow fast.

The usual picture of the First World War is one of slaughter in the mud and trenches in France and Belgium. For the Levantines in Turkey it was rather different. The German propaganda machine played on the resentment of the nationalist Young Turks, led by Enver Pasha, against the privileged Europeans and Levantines, who profited from the capitulations and controlled the state revenues, most of which went to service the Ottoman national debt to the European banks. Kaiser Wilhelm was looking for a way to open the gates for Germany towards India. Hoping to exploit the power of religion in the Middle East and beyond, he announced to the Islamic world that he had become a Muslim and that, with the Ottoman Caliph beside him, he would protect all Muslims against the British. You all know the result of that.

In October 1914 the Ottoman government unilaterally abolished the capitulations. The OCM company therefore had to register itself as a Turkish company, which meant that it now depended on the Turkish government rather than the British government for protection. In November Turkey and Britain were at war. What now should be the position of the OCM and its European owners? The question of loyalty that faced the directors was difficult, similar to that of the Anglo-Argentines during the Falklands war.

The wool mills had for years been providing cloth to the Ottoman army for uniforms. Now the Ottoman government threatened to sequestrate the mills unless they continued to supply this material to them. The owners of the OCM, although technically British, French or Italian citizens, had lived in Turkey for hundreds of years and were treated by the British government as if they were Ottoman citizens. Should they resist Ottoman demands, or collaborate?

In the end, they decided that firstly, as the war was sure to be a short one, they should keep hold of the company so that they could resume business afterwards and that, secondly, supplying cloth for uniforms would make little difference to the outcome of the war. In any case, even if they refused to collaborate, the Ottomans would surely confiscate the company and still get their cloth. So, they collaborated.

There now enters on the scene the remarkable Ottoman governor of Smyrna, Evrenoszadeh Rahmi Bey, whose statue still stands in Izmir. This man came from an old landowning family of Salonika and was one of the original modernising Young Turks. While in the rest of Turkey the authorities imprisoned or exiled all Europeans of hostile nations to the interior, Rahmi Bey gave the Europeans of Smyrna twelve days to leave, if they wished. If they wished to stay, he promised, he would protect them. And, indeed, he did protect them. Not only did he ensure that the Ottoman government paid for the cloth they received from the OCM, he also allowed the Europeans to keep their guns and to go hunting with them whenever and wherever they wished, even giving them an escort to make sure that nobody troubled them.

Occasionally Rahmi Bey came under pressure from Enver Pasha and his pro-German party and was obliged to demonstrate his patriotism by locking up some Levantines for a few days, but he treated them always with the greatest courtesy. From the beginning he had been opposed to the war, foreseeing the disaster that was to befall Turkey at the end of it. In spite of that, at the end of the war the Allies imprisoned him and exiled him to Malta, as being of the war party, and it took a lot of effort from the Levantine families to have him released. After the signing of the peace, as a reward, the company made him a director.

After the war the OCM found itself with huge stocks of carpets which, for lack of shipping, they had been unable to move. They were thus able to profit from the backlog of demand in the USA and in the victorious countries of Europe, which had been starved of imports all this time. The economies of Germany and Austro-Hungary, however, which had previously been very good markets, were now destroyed. However, the company now had a problem in Turkey with production, in that the company had lost many of its Armenian weavers during the events of 1915 and 1916.

The end of war did not bring peace to Turkey. In May 1919 a Greek army landed in Smyrna and quickly advanced far into Anatolia. Their advance was accompanied by much destruction, particularly of the carpet weaving town of Ghiordes [Gördes], which was destroyed in 1921. Anatolian carpet production practically came to a halt.

In the spring of 1922 Mustafa Kemal’s army pushed the Greeks steadily west. The retreating Greek army set fire to everything before it. On 9th September the Turkish army entered Smyrna. Four days later the city caught fire. It burned from 13th-16th September and much of Smyrna was destroyed. Some two thousand lives were lost. There is still, even today, much argument as to who was responsible, each side blaming the other and both blaming the Armenians.

There were dreadful scenes at the harbour. The Allied naval vessels in the bay looked on as Greeks and Armenians, pushed by the crowds behind, plunged into the sea to escape the flames. The OCM head office on the quay was burned and its entire stock of carpets was lost. The American Tobacco Company also lost its entire stock of tobacco. A curious story about the fire is that all the paper money in the banks was burned, as were the stocks of paper. This meant that for some time new bank notes had to be printed on very small pieces of paper.

These colossal losses became the subject of insurance claims into which politics entered in a big way. In brief, the goods had not been insured against war risk, since the owners had seen no risk of war. The Americans therefore were anxious not to blame the Turkish army for the fire. The British, for their part, were interested in the oilfields of Mosul and also had no wish to antagonise the new Turkish government. The record is therefore murky.

The companies claimed against the insurance companies for accidental damage, which they refused. A test court case in 1923 found in favour of the insurance companies, in other words, that the fire was an act of war and not an accident. This wiped £100,000 sterling off the OCM books, equivalent to about US$ 8m today. This decision, did however, later enable the companies to claim damages for their losses from the Turkish government by way of war reparations.

But these are small matters in comparison to what followed. The collapse of the Ottoman empire after the Great War, followed by the victory of the new Turkish army under Ataturk, led to the founding of the new Turkish republic. There followed the great population exchanges in 1924, but – what was the effect of this upheaval on the carpet company?

In the post-war years the OCM found that it had now lost all its weavers in Turkey. The Armenians had gone in 1915, and now they had lost the Greek weavers. The only solution was to establish looms in Athens and on Rhodes. Rhodes, being still under Italian occupation, supplied the Italian market free of customs duty and did well for a while. In Turkey the taxes on trade imposed by the new republic, as well as the threat of trouble coming from Bolshevik Russia, drove the traders of Persian and Caucasian carpets in Constantinople to the safety of London, where their businesses thrived in the bonded warehouses that were given to them beside the docks.

When the European governments imposed protective trade tariffs, by way of imperial preference, Indian carpets were imported into England and Algerian carpets were imported into France almost duty free, to the great detriment of the Turkish trade, which was obstructed by heavy import duties in both countries. The once thriving Turkish carpet industry, employing many tens of thousands of spinners, dyers and weavers, was destroyed by war, politics, taxes and political instability.

In 1928 the Turkish government changed its attitude towards commerce and relaxed its tax regime, which led to a brief and spectacular boom in business which, but for the Wall Street crash of 1929, might have continued. Çolakzadeh, the only Turkish substantial carpet exporter who had survived independently of the OCM, was clever enough to see it coming and was able to sell his stocks in New York just in time before their value evaporated. Once again, the illiterate weavers in the villages of Turkey, and also Iran, found themselves out of work as a consequence of follies committed by educated people of whom they had never heard.

This has been a patchwork of a story. I have outlined it here for you in the hope that you might consider the history of this company and the times that it lived in, and ask yourselves some questions: some questions about nationality, sovereignty, the necessity for maintaining conditions favourable for trade and industry, the need at the same time for control of banks and commercial institutions, and the need for economic and political stability, without sclerosis. Today we are all faced with these questions, but we are not the first to have faced them. Many of today’s problems faced us a hundred years ago. If we can reflect on the mistakes that were made then, perhaps we can come up with some better solutions now.

Notes: 1- Antony Wynn is the author of the ‘Three Camels to Smyrna: Times of War and Peace in Turkey, Persia, India, Afghanistan & Nepal 1907-1986, The Story of the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers Company’- 288 pages, 2008 - segment

2- To read the interview conducted post Antony Wynn’s talk in 2012, click here:

Antony Wynn giving a lecture to members of the Anglo-Turkish Society on the subject of his book, post publication, January 2012