Historical obituary notices | Osman Streater | Andrew Mango | Alex Baltazzi | Livio Missir | Giovanni Scognamillo | Padre Stefano Negro

Obituary by David Barchard:

In November 1938, after the death of Kemal Atatürk, the pupils of the English High School for Boys filed past the catafalque of the dead leader in the Dolmabahçe Palace in Istanbul. Six decades later one of them was to produce the standard biography of Atatürk and become the acknowledged doyen of Turkish studies in Britain in the late 20th century, though without ever actually occupying an academic position.

Andrew Mango was born in June 1926 in a home a few minutes walk from Taksim Square. Mango’s grandfather had been a wealthy ship-owner. His father, a Cambridge-educated maritime lawyer was a naturalized British subject; his mother a White Russian refugee from the Russian revolution in Baku. Andrew’s uncle married the daughter of Alexander Karatheodori, a famous Greek Ottoman statesman under Sultan Abdulhamid.

With such a multilingual background Mango grew up an instinctive polyglot, speaking French at home, English, pre-revolutionary Russian, Greek and Turkish, all more or less at native level.

The family lost its fortune after the Great War through ill-judged trading in dates and tobacco with the Bolsheviks. When most of the British colony departed in 1928, the Mangos nevertheless stayed on in Turkey. 1930s and 1940s post-Ottoman Istanbul was a dispiriting place, especially for its non-Turkish population. Mango and his two highly talented brothers, one of whom was destined to become a professor at Oxford, knew that they had little future in Turkey.

After a late teenage spell working in the British Embassy in Ankara around the end of World War II, Mango moved to London, gained a degree in Arabic and Persian from SOAS and a doctorate there in 1955 with a thesis on Alexander the Great in Classical Persian literature. In 1958 with a family to support, he gave up ideas of an academic career, becoming BBC Turkish Programme Organiser, holding the post until he was promoted to Head of the BBC South European Service in 1972. Energetic (he would write a 1000 words of his current book each day before travelling to work by bus from Barnes to Bush House), lively, and immensely knowledgeable on Ottoman and Republican Turkish history, he swiftly gained a reputation as one of the UK’s few specialists on the country. The Turkish Service became a port of call for Turkish academics, politicians, and writers visiting London who would be royally entertained from a legendary drinks cabinet amid a flow of witty and learned conversation.

The Mangos had left Turkey with less than happy memories and in early decades, Mango’s initial attitudes to the country were often those of an émigré. But as his personal acquaintance with Turkey and its leading figures deepened into friendship he saw the Turkish side of the story with increasing clarity and was never shy of putting it in Britain at a time when friends of the Turks qualified to talk about the country were few and far between, regarded as a friend by Turkish politicians of every shade.

His early books, written while Turkish Programme Organizer, were straightforward introductions to Turkey, but after 1974, with Turkey’s relations with the West frayed in the wake of the Cyprus crisis, he produced a stream of seminar papers and think-tank reports establishing him as a regional specialist, with detailed knowledge of his subject matter and rigorous intellectual standards dwarfing those of other speakers. He was also a charming dining companion, never so happy as when talking amusingly, accompanied by a bottle or two of good wine or champagne.

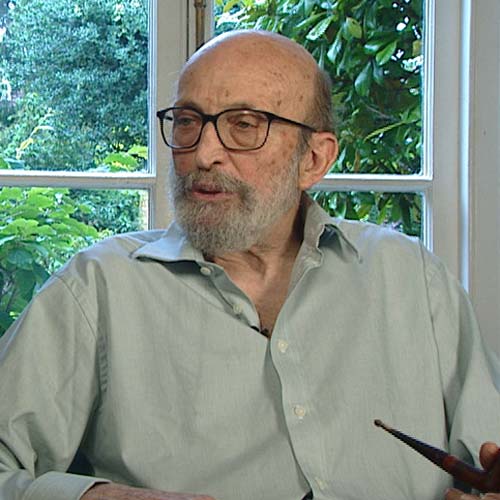

The most intellectually fertile period of his life came in nearly three decades after retirement, as he produced a stream of acclaimed books of which his standard biography of Atatürk is simply the best known: there are few if any recent books on Turkey of comparable quality. Travelling frequently to Turkey he became an iconic presence on Turkish television with his fluent Turkish and striking beard.

In the summer of 2013 however, he courted possible unpopularity signing a public letter to The Times condemning violence used against demonstrators in Istanbul, his only partisan pronouncement on Turkish politics in decades.

Nevertheless Turkey’s Foreign Minister, Ahmet Davutoglu paid Mango a striking compliment after his death in a message of condolence to his family, declaring that “his work and contribution [to Turkish studies] will continue to draw respect from generations to come.”

He is survived by his wife, Mary, a daughter, and a son.

Andrew James Alexander Mango, born Istanbul 14 June 1926.

Died Barnes, London 6 July 2014.

Married Mary Muir, 1957.

Interview with Dr. Andrew Mango: Turkey’s Walk from 1923 to 2023: A Critique of the Past and Recent Political Challenges.

Information on his ancestry.