The Interviewees

Interview with Miguel Selvelli, July 2020

1- Dear Miguel, as an active member of the LHF-Istanbul group, we already had time to speak and hear about the interesting story of your family in previous occasions, including the conference held at the Italian cultural institute in September 2016. Would you now be so kind to tell again something about it for the readers of our website?

I’m very proud to have the opportunity of telling the story of my ancestors for the LHF website, an institution that has played an important role in my life in these recent years, motivating me to go deeper in my research, and giving me the opportunity to know many amazing people dealing with similar topics in Turkey and around the world.

I can say that the fascination with the Ottoman Levantine past of my family has been of paramount importance in my life path, as it pushed me to come to Istanbul in 2006-2007 in order to learn more about it. I was born in Italy, as well as my father, but my grandfather Guido was born in Istanbul (in 1917), as were his father Luigi (in 1891) and grandfather Italo (in 1863). It was Michele Selvelli (1825-1895), the father of Italo, the one who decided to come to Istanbul around 1850, as he was forced to escape from his hometown (Fano, close to Ancona, on the Adriatic coast) due to the contingent political situation.

In order to better understand this, please allow me to give some information about the historical and political context of the Italian peninsula during those years.

In the first half of the 19th century Italy was nothing more than a geographical concept. The whole Southern region, including Sicily, was under the rule of the Spanish Bourbon family, while most of Central Italy was under the rule of the Pope. In fact, if nowadays the territory of the Vatican State is limited to that small neighborhood in Rome, this was only given after a long struggle conducted by the Italian people against the power of the Pope during the 19th century, a struggle that was finalized only in September 1870 with the ‘conquest’ of Rome. The whole North-eastern region (including key-cities such as Milano and Venice) was under the rule of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire. There where then some minor independent entities, like the duchies of Parma and Modena, the grand-duchy of Toscana, and the kingdom of Piemonte, and Sardinia was ruled by the Savoia family. This last kingdom, under the rule of king Vittorio Emanuele II, had a fundamental (although problematic) role in the independence struggle that gave its first results in 1861, with the official declaration of unity and independence of Italy, and the choice of Torino as her first capital city. In any case, what is now defined in history books as the 1st war of Independence, that took place in 1848-49, was an astonishing collective insurrection of the Italian people against the foreign powers, leading to several experiences of radical democracy in many cities including Venice and Rome. During these months Mazzini and Garibaldi also happened to play an important role in the struggle. But in the end, after 18 months of struggles, the revolutionary movement was crushed down by the foreign powers and the Vatican State, who then started a harsh repression against all those who had taken part in the struggle. This is the reason why thousands of patriots, during the summer of 1849, decided to leave the Italian peninsula searching for a refuge somewhere else. Between them, according to my family’s oral history, was Michele Selvelli, who was from Fano (small town close to Ancona) and eventually reached the Ottoman capital in the early 1850s. (Although I was not able to find a proper record regarding the participation of my ancestor Michele Selvelli to the independence struggle, I found the name of his brother Aldebrando mentioned in a book dedicated to the history of the Ancona insurrection in May-June 1849 and the following siege brought by the Austrians, who had been called by the Pope to help him take back the city).

The oldest document I’ve been able to retrieve regarding the presence of Michele Selvelli (1825-1895) in Istanbul is his marriage certificate in the Santa Maria Draperis Church on Istiklal Street that took place on the 16th September 1855 between him and Maria Sigala (1837-1904) a Catholic born in Istanbul within a family originally from the Greek island of Syros. The witnesses of the wedding were Lorenzo Montagna from Verona and Anna Cappello from Syros.

The first daughter of the couple was Luisa, born in 1856, but she died shortly after. Their first surviving son was Felice Romeo Selvelli, born on 25/4/1858. I like to imagine that the name Felice was given to him in memory of the famous Italian patriot (although many today would call him a ‘terrorist’) Felice Orsini, who had been recently executed in Paris after his failed attempt to kill the emperor Napoleon III with a bomb thrown in to his carriage in front of the Opera Theatre. Felice was followed by the birth of the second son Giorgio Natale on 15/11/1860, who unfortunately would die prematurely in 1884 of tuberculosis.

The following important record concerning the presence of Michele Selvelli in Istanbul concerns his inscription in the Società Operaia Italiana di Mutuo Soccorso, as he became its 79th member in June 1863 (few weeks after the official foundation of the Society, that took place on the 17th May), declaring to be working as a ‘beer producer’.

On 10/11/1863 the third son of the couple was born: Italo Giovanni Salvatore Selvelli. It’s interesting to notice that the first name Italo was given by a patriot in exile, who as many others in his same condition never stopped following the news coming from their homeland, as in March 1861 the (although still partial) unity and independence of Italy had been officially declared.

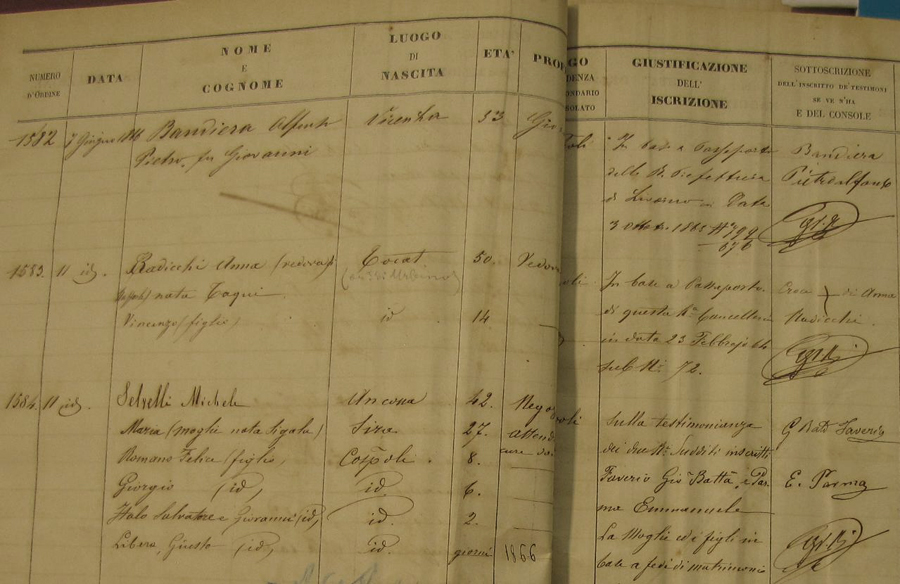

As we can see from this document (image 1), on the 7th June 1866, few days after the birth of their 4th son Giusto Libero, Michele Selvelli and his wife Maria Sigala finally decided to register their presence in Istanbul through the Italian Embassy. In order to do this, they brought as testimonies two distinguished members of the Italian community in Istanbul: Giovanni Battista Faverio (vice president of the Società Operaia) and the notable tradesman Emanuele Parma.

In 1868 the only surviving daughter of Michele Selvelli and Maria Sigala was born, named Maddalena Speranza.

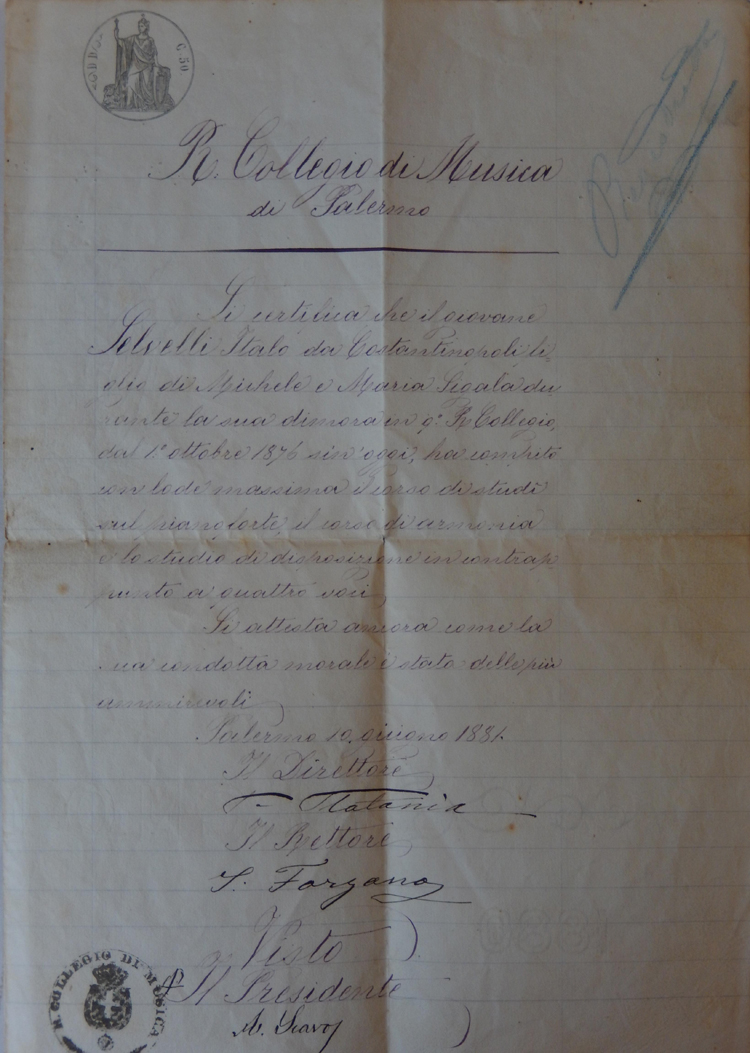

What we instead learn from this diploma (image 2), belonging to our family archives, is that Italo Selvelli (1863-1918) in September 1876 was sent to study music at the Royal Conservatory in Palermo, where he graduated in 1881, deciding then to come back to Istanbul. At that point, as it’s possible to retrieve from the local sources of the time, especially the cultural ads in newspapers and the commercial yearbooks, the three brothers Felice, Italo and Giusto all started earning their living through the practice of music.

Felice worked since 1883 until his death in 1907 as a piano tuner, and since 1896 he was employed in this role within the prestigious piano shop owned by the Keller brothers in Hazzopulo Passage no.25.

Italo, thanks to his talent and his foreign education, was the most successful of the brothers: in fact he immediately started to work as a private music professor, but in 1892 he was appointed by the Ottoman state as the instructor for the military band in Tophane. At some point, according to the information provided by the late researcher Vedat Kosal, he even became the ‘composition’ teacher of Ayşe Sultan (1887-1960) - the daughter of sultan Abdulhamid II - who developed a particular talent in music studying with the best instructors of that time in Istanbul.

On the 7/5/1889 issue of the newspaper La Turquie it was possible to read an article praising the concert held for the Iranian ambassador Mirza Muhsin Khan at the Teutonia Theater by Italo Selvelli together with the Euterpe chorus, founded by my great-great-grandfather just some months before.

As we can see in the 1891 Ottoman yearbook of commerce, all the three Selvelli brothers were dealing with music, while their father Michele Selvelli eventually abandoned the sector of beer production in order to deal with the production of lemonade and carbonated water, and in 1894 (one year before his death) he was employed in this same field by the Maison Leon Schor.

According to what we learn from the 1895 yearbook, Italo Selvelli in that year was appointed ‘Director of the Music Military School of the Artillery Command’. We should thus understand that Italo Selvelli was a really busy person, as he was at the same time working as a private teacher, a military band instructor, a piano concertist and a composer.

The first composition we know about is the ‘Marche Triomphale’ dedicated by Italo Selvelli to the Grand Master of Ceremonies Münir Pasha (image 3). As noticed by the researcher Evren Kutlay Baydar in her book, the only Ottoman military success of those years being the short Greek-Ottoman war in May 1897, the march must have been composed shortly after that.

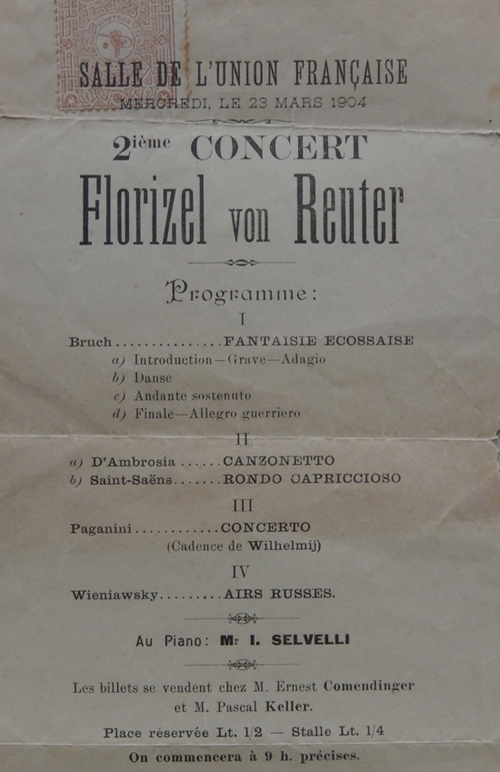

Between the many appearances of Italo Selvelli as a piano concertist in the musical venues of Istanbul, in our family archive we keep trace of a performance as piano accompaniment for the violinist prodigy Floritzel von Reuter (1890-1985), at the Union Francaise in Tepebaşı during his European tour in 1904 (image 4).

For the many other concerts given by Italo Selvelli during those years, the best source I know is Evren Kutlay Baydar’s book.

Concerning their private lives, Felice Selvelli married in 1883 with Maria Calavassi and had two sons (Michele in 1883 and Oscar in 1890) and two daughters (Anna in 1888 and Antonia in 1896) Italo married in 1889 with Anna Maria Pussich and they also had two sons (Luigi in 1891 and Antonio in 1896) and two daughters (Carlotta in 1900 and Maria Elda in 1902).

Giusto married in 1889 with Lucrezia Seminati, the sister of the architect Delfo Seminati, but they had only one daughter, Gemma, in 1890.

Shortly after the death of their elder brother Felice in 1907, both Italo and Giusto found themselves involved in the enthusiastic atmosphere that followed the so called ‘Young Turk Revolution’, the famous rebellion of some Ottoman military officers linked to the CUP (Committee of Union and Progress) in the Thessaloniki and Macedonian region, that in July 1908 forced Sultan Abdulhamid II to re-enforce the Constitutional system he had suspended in 1878. The event was warmly welcomed by the most progressive section of the Ottoman population, and especially by the non-Muslim communities.

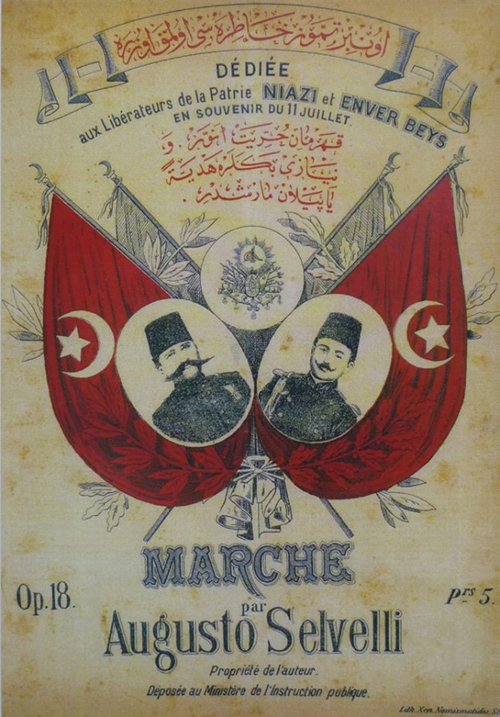

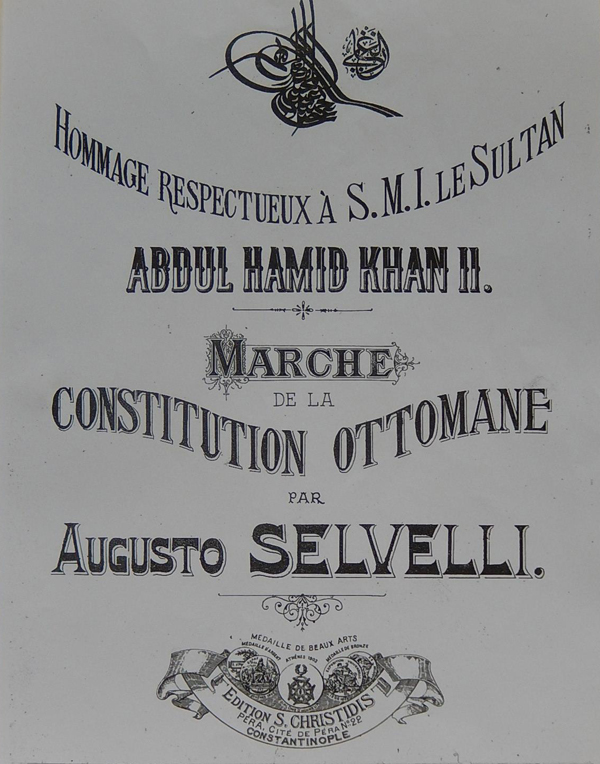

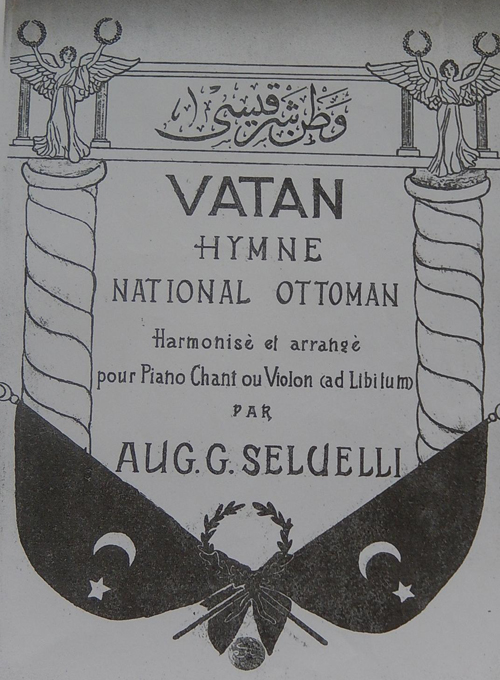

As we can see from these images (image 5, 6, 7, 8), apart from Italo also Giusto (often using the name of Augusto) was strongly inspired by these political developments, and produced several marches in order to celebrate both the heroes of the revolution Enver Bey (future Minister of War Enver Pasha) and Niyazi Bey (to be noticed that Resna was his place of birth, in nowadays Northern Macedonia), as well as the Sultan himself for allowing this constitutional reform.

In April 1909, however, there was a counter-coup attempt, orchestrated by the most conservative sections of the army and the bureaucracy in order to suppress the constitutional reforms. As the Sultan’s attitude during this unfortunate event was seen as ambiguous, the CUP decided to depose and exile him from Istanbul, bringing to the throne his younger brother Mehmet Reşat (Sultan Mehmet V), who was in fact a very weak political figure.

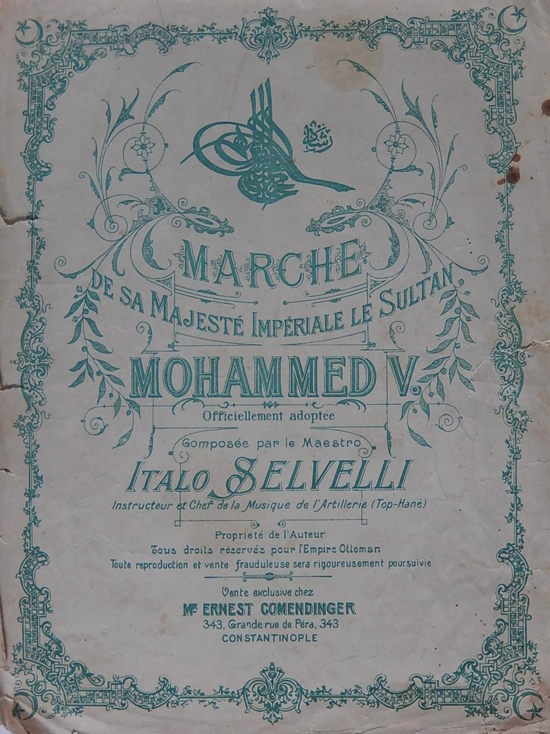

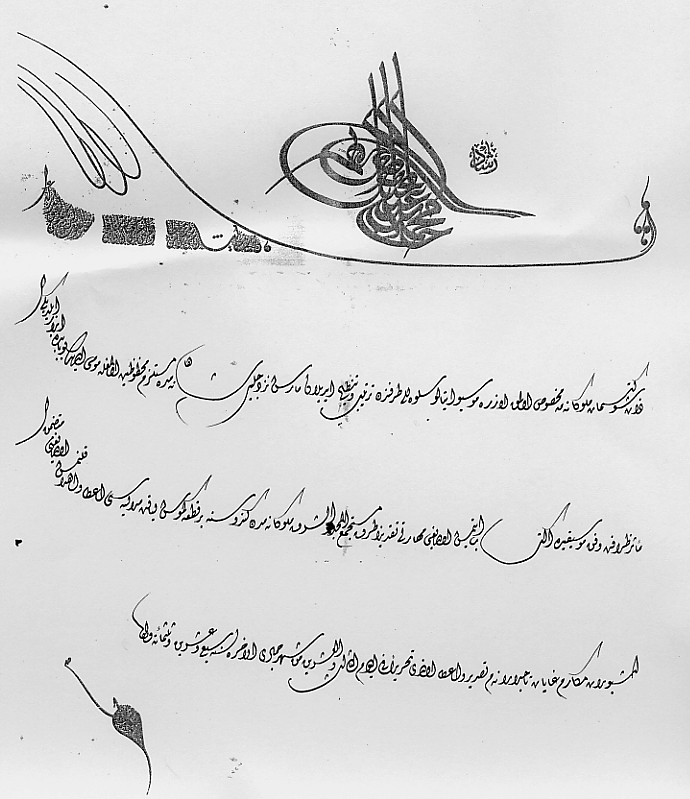

Nonetheless, the new Sultan decided to call for an open competition in order to define the new official march of the Ottoman Empire, to be used as a National Anthem during official occasions. At the end of the selection, the piece chosen was the composition of Italo Selvelli (image 9), who was awarded with this official firman and a silver medal by Sultan Mehmet Reşat on the 12th July 1909 (image 10). This composition known as Reşadiye March is to be considered as the last original anthem of the Ottoman Empire, as the following and last Sultan Mehmet VI (1918-1922) decided to adopt once again a march that had already been in use during the 19th century.

2- It’s very interesting to follow how the story of your family happens to be intersecting with many important political events of that period. Was the Resadiye March the maximum achievement reached by your ancestors in the Ottoman field of culture and art, or is there something else?

In the musical field, I would say that without any doubt this was the maximum achievement. But without going into too much detail I would like to briefly introduce another branch of my family, which is the Seminati one, corresponding to the maternal side of my grandfather. Giuseppe Seminati (born in 1826 in Ranica, a small town close to Bergamo) was a construction worker who arrived in Istanbul in the late 1850s through Bucharest, so I guess that his arrival was not motivated by political issues. He married with a woman called Anna Trojanovich (Dubrovnik 1835 – Istanbul 1911) and had two sons and two daughters. The second son was Delfo Seminati (Istanbul 1864 – 1942), who ended up establishing himself as a renowned architect in the early 20th century. Between his several projects and contributions, I would say that the most relevant one is the beautiful Hıdiv Kasrı in Kanlıca (Asian side of the Bosphorus, just after the second bridge), designed by him and Antonio Lasciac (Gorizia 1856 – Cairo 1946) as a summer residence for Abbas Hilmi II (1874-1944), the last khedive (viceroy) of Egypt. Delfo married a Catholic Armenian whose name was Malvina Kasparian (Izmir 1871 – Istanbul 1914). Their daughter Irma (Istanbul 1896-1917) was my great-grandmother, as in 1916 she married with the son of Italo, Luigi Selvelli (Istanbul 1891-1958). Unfortunately she died of tuberculosis shortly after giving birth to my grandfather Guido (Istanbul 1917- Gorizia 1979).

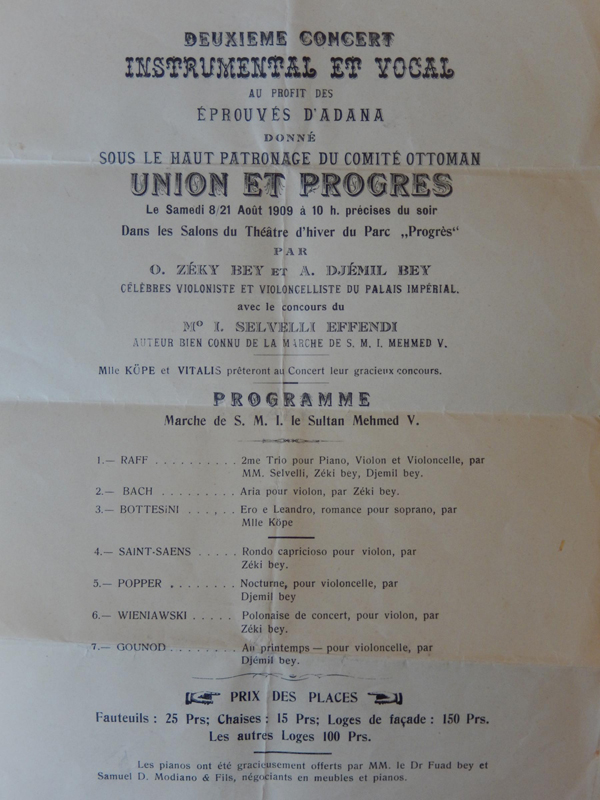

Going back to the artistic production of the Selvelli branch of the family, what I found really interesting in terms of social and political history is a concert invitation belonging to our family archive (image 11): here, in fact, we can see that a nice musical evening (the second edition!) has been organized ‘under the high patronage’ of CUP in order to raise some funds for the ‘victims of Adana’. What was the whole thing about?

The event is not very well known, but what happened is that during the counter-coup attempt in April 1909, some sections of the population and the military tried to take advantage of the situation of widespread social unrest converting it into an open aggression against the Christian population of the Anatolian city of Adana, particularly against the Armenians. Sources are still contradictory, but several thousands of people are believed to have been killed in the massacres.

So it’s really interesting to see that the CUP, or at least some sections of it, seemed sensitive towards the topic to the point of patronizing such an event in favour of the victims. What is also interesting to notice is the participation, together with Italo Selvelli, of the musicians Zeki and Cemil Bey. These names, appearing altogether also in this nice picture likely taken in Thessaloniki (image 12), are indeed very important musical figures of the time, specially Zeki Bey, who is none other than Zeki Osman Üngör, the composer of the Independence March (Istiklal March) that since 1930 has been adopted as the National Anthem of Turkey, together with the text written by Mehmet Akif Ersoy in 1921.

3- We know that within few years, the Ottoman government led by the CUP found itself faced with very difficult domestic and international pressures, both on the social and political level, until the final explosion of the First World War. How did all these events ended up influencing the life of your ancestors in Istanbul?

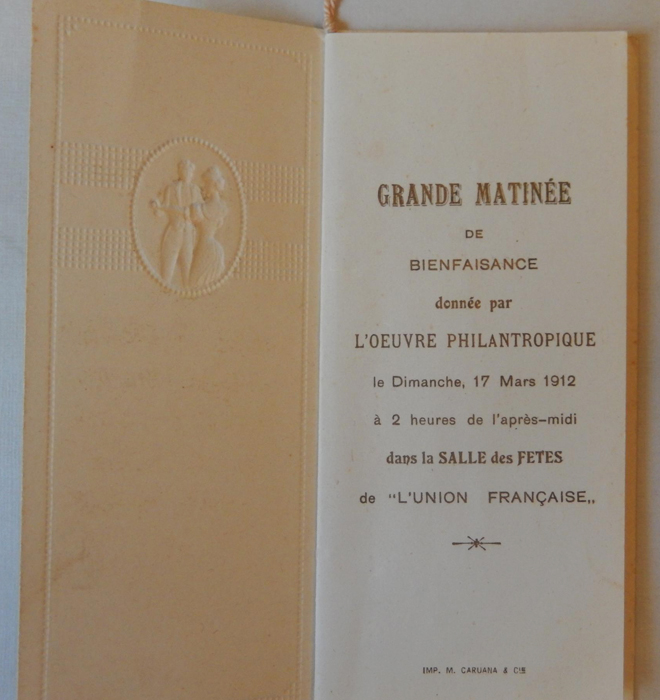

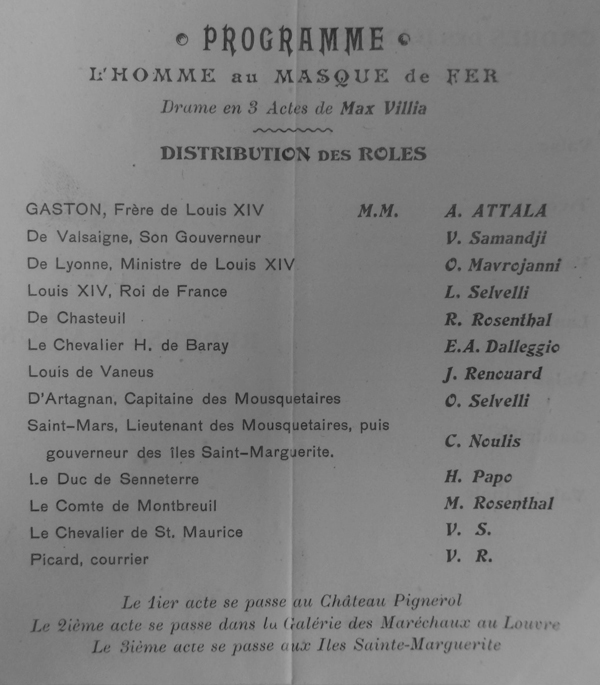

Unfortunately, after the Italian military intervention in Libya in September 1911, the relations between the Ottoman government and its Italian citizens seriously deteriorated, and most of them were actually forced to leave the country. But this was not true for the Selvelli family, as we can see from this theatre play (image 13) taking place in March 1912 at the Union Francaise, where the two young cousins Luigi (my great-grandfather, son of Italo) and Oscar (son of Felice) happen to be merrily participating, respectively in the roles of the King of France Louis XVI and D’Artagnan. At the same time, we learn from the 1912 and 1914 yearbooks that Italo Selvelli came to be appointed as Director of the Imperial music orchestra in Tophane. However, from Selçuk Alimdar’s book we can learn that after the breakout of the Italo-Ottoman war in 1911, the sultan interrupted the adoption of Italo Selvelli’s composition as the official Imperial anthem, substituting it with a previously adopted march.

4- And what happened then with the conflagration of the First World War?

I don’t have any specific information or archive material regarding the years of the war, but we can easily say that, as for many other Levantine things, it was the event that marked the end of an era for my family. Very significantly, Italo Selvelli died in May 1918 (when he was only 55 years old) a few weeks of short of the demise of sultan Mehmet V. According to my family’s oral history, it seems that in the last years of his life he had been involved as a music instructor in the establishment of the Istanbul Conservatory (Darülbedayi), but I could never find any source confirming this information.

What seems sure is that the mother of the famous musician and composer Cemal Reşit Rey (1904-1985), Fethiye Hanım (at the same time a niece of the famous painter Osman Hamdi Bey), had been studying music with Italo Selvelli.

5- And after the First World War?

As I stated before, it was the beginning of the end. In the new world order that came out of the War, constituted by national states based on ethnic, religious and linguistic homogeneity, it became more and more difficult for them to find a space. My great-grandfather Luigi (1891-1958) in any case decided to keep living in Istanbul all his life, but it’s sad to learn that in that age of growing nationalisms he as well felt the need to stick to an ‘imagined Italian identity’, becoming a member of the Italian fascist party in Istanbul (yes, there was such an office in Istanbul during the late 1920s and 1930s!). I prefer to think that he did not have a very clear idea of what the whole thing was about, as he never traveled to Italy before the end of the Second World War. But since what I understand, in those years in Istanbul many Italians felt the need to stick to this new strong national identity in reaction to what was happening around them at a social and political level.

6- What was he doing as a profession?

After that ‘golden generation’ born in the 1860s, there was never any more such an artistic outburst in the family. My great-grandfather Luigi worked all his life as a bank employee and in the field of trade and small businesses. After the early loss of his wife Irma Seminati in 1917, in the early 1920s he married Maria Zellich (1899-1962), member of a Croatian origin renowned family that played a pivotal role in the printing industry during the last decades of the Ottoman Empire and also in the early Republican period; but they never had any other children.

My grandfather Guido was thus the only child: he studied at the French Saint Michel School in Osmanbey and then at the Italian High School in Tophane. After that in 1937 he decided to go to study foreign languages and literature at the university in Venice. I guess in those years he also had a sort of curiosity and fascination with the nature of his Italian identity and therefore felt the need to go check the situation there in first person, despite of the troubled period.

In the end what happened is that the Second World War burst out and he was called up to the Italian Army as a soldier, and was sent to the area of Gorizia, in the North-East of the country. There he ended up meeting my grandmother. In a very hasty situation they got married in 1942, before being forced to separate again because of the evolution of the war.

After these very troubled and difficult war years my grandfather Guido, who had left Istanbul just few years earlier with the idea of studying at the university in Venice, found himself married, father of a small kid and eventually settled in the area of Gorizia, where he ended up living all his life until his death in 1979, working as a sales agent for the small business of his father-in-law.

7- Did you have the chance to meet him?

No, unfortunately not. But I think that unconsciously his aura and his somehow mysterious ‘Ottoman’ origins always cast a very strong spell on me, pushing me to leave everything behind and move to Istanbul in 2006-2007.

8- You clearly have a strong interest and passion in both the history of your family and the historical context of the late Ottoman period where their lives have been taking place. How have you been developing your studies? Do you ever plan to write anything more systematic about these topics?

Thanks for your words. I never took a formal academic education in the field of Ottoman history, everything I learnt was through my own studies, based on books and different sources in Turkish, English, French and Italian language. When I arrived in Istanbul I knew practically nothing about Ottoman history, and I had just very basic information about the history of my family. We didn’t even know where and if the Selvelli’s tomb still existed. The first step was to find the tomb in the Feriköy Catholic cemetery (image 14), and to have the possibility to check the cemetery registers concerning my family in its archive. Then slowly slowly I went on searching for similar files in the Beyoğlu and Osmanbey Catholic churches. And then of course in the archives of the Società Operaia di Mutuo Soccorso. I can say that in 2012 I had more or less been able to rebuild the whole genealogical tree of the family, including also the other branches. But I still had had no real time or passion for investigating more thoroughly the whole historical context that was behind the lives of my ancestors.

And then suddenly everything changed one day in March 2013, when I went to visit for the first time the Pera Museum, and I discovered the amazing figures of Osman Hamdi Bey (1842-1910), his father Ibrahim Edhem Pasha (1819-1893) and the sultan Murat V (1840-1904), the first member of the Ottoman dynasty to become a mason, who was then deposed in 1876 shortly after having ascended to the throne, being declared as ‘mad’. Their liminal identities which were always on the threshold between traditional Ottoman culture and European-inspired modernization strongly fascinated me and pushed me to investigate better that amazing period of cultural struggles and contaminations corresponding to the Tanzimat reforms and the last decades of the Ottoman empire. Of course I was helped in this endeavor by the fact that at that point my Turkish had become fluent, and I was therefore able to take advantage from the astonishing amount of quality books published in Turkey on historiographical issues, by researchers who are at the same time able to read Ottoman script, something I was never able to cope with.

Slowly slowly my notes and my knowledge started to become wider and deeper, and I realized that I had in my hands a valuable material regarding the contributions in the field of art, culture and politics provided by Italian exiles who had come to Istanbul in the years of the Tanzimat. Of course my ideal point of reference was my ancestor Michele Selvelli (the beer producer, father of Italo) and for some time I tried to find the way to include my family’s stories in the historical frame. But in the end I decided to leave them out, keeping them merely as a ‘blind spot’, while focusing instead on all the other amazing stories I had discovered. Finally I ended up writing a book on the topic, whose publication is due in Italy at the beginning of 2021. The provisional title is ‘Ancestors in Constantinople. Italian exiles in the age of Ottoman reformism 1828-1878’. It’s in Italian, but of course I hope it will end up raising some interest and it will eventually be translated to other languages.

9- I suppose research of this nature could never end as you can widen the net to bring in the story of the various side branches of the family through the generations and go deeper into the convulsions of politics and war that curtailed these Levantines from maintaining their community cohesion past these watersheds. If you had more time and perhaps more help in accessing the Ottoman archives, which area of the wider family story would you like to pursue to tie up any loose ends?

Yes, you are absolutely right, sometimes it just feels like a never-ending endeavour. That’s why in the case of my book I decided to limit the time-frame to those 50 years between 1828 (the arrival of Giuseppe Donizetti to Istanbul in order to work as the new chef of the military band for the sultan Mahmut II) and 1878, which is in many ways a turning point in the late history of Ottoman empire and the beginning of 30 years of unconditional rule by the sultan Abdulhamid II, after his first two years were spent somehow ‘searching for compromises’.

Coming back to your question, if I had time and energy, I would love to dig more deeply in the early years of the 20th century, until the explosion of the 1st World war: the role of Levantine individuals and communities in the cultural, social and political upheaval that made the 1908 Constitutional revolution possible. And even more specifically, how was their emotional involvement in it, and how their support and fascination with it evolved during those first troubled years of CUP rule, marked by Italy’s invasion of Libya and the Balkan wars. Based on newspapers, diaries and letters, I would love to study the feelings of the Levantines (specially the Italian ones) towards all these events, trying to understand how they positioned themselves in terms of identity and cultural attachment.

10- The LHF is an organisation which is now 10 years so perhaps maturing and slowing down as Covid curtails so much culture around the world. In your wisdom based on extensive research in different geographies and media, how would advise we concentrate our meagre resources to better serve people like you who want to know more on their Levantine ancestry?

I think LHF is doing really a great job, and I’m proud to be an active member of it. I think the international conferences are one of its most amazing activities: I’m now thinking of the ones in London 2016 and Athens 2018 and they come to my mind as really beautiful days where you have the opportunity to learn and share knowledge while at the same time meeting old friends or new interesting people.

Regarding any suggestions, I don’t know how easy and feasible this could be, but maybe a sort of research fund could be established in order to allow people interested in research to dedicate more time to their investigations while at the same time establishing a more direct and vinculating connection with the LHF interests and possibly some Levantine families who may have the will and interest to support researches dealing somehow with their ancestors and their economic/cultural activities.

11- You now know many of the languages your ancestors either spoke or were surrounded by and have walked the same streets and entered the same buildings in the years you have lived in Istanbul. Do you think at times you see their world clearer and understand their determination to succeed in this very alien environment away from their ‘homeland’ for the first generation and ‘imagined homeland’ for subsequent generations? And finally, what is your point of view on the future of Levantine culture in the 21st century?

Your questions are becoming so sophisticated, thanks a lot for this. Sincerely no, I don’t think that I can see their world more ‘clearly’ if this is meant in a rational way, due to the historical distance and capacity to analyze all the data in a way that maybe was not directly available to them. What I think is that by learning as much as possible about their epoch, and at the same time by experiencing as much as possible the same languages and urban spaces that they did, I can try to develop as much ‘empathy’ as possible at an emotional level. In fact I have become so sensitive at this level that still now I can find myself with tears in my eyes when looking at some old pictures of my Levantine family. Sometimes I think that this is just a romantic nostalgia, but on other occasions I think that what happened specially in Istanbul in those last 60-70 years of the Ottoman Empire – that amazing complexity of overlapping lives, cultures, languages, melodies and mutual efforts for understanding and accepting each other no matter the differences – was really a rare event in the history of human civilization. In my personal opinion all this is now finished, as there are no longer the social and political conditions for a ‘Levantine existence’ or a ‘Levantine way of life’ in that specific geography. As researchers and/or descendants of those families, we can just try to keep alive in the most genuine way the memories of those lives, in order to provide an ideal example of co-existence between different cultures, languages and religions, to be taken as an inspiration for the present and the future, but of course impossible to be replicated.

If I had to define and actualize what is for me ‘to be Levantine’, I would say that it’s to feel attracted by a geography that doesn’t belong to you by birth. It’s the will to establish somewhere far away from your family roots, and to be able to find your way in the new geography not because of a capital or some other material privilege you dispose and take advantage of, but thanks to your social abilities and your capacity to adapt. This requires a fundamental disposition to be humble, to know, accept and respect the cultural habits and customs of your ‘new home’, and of course the will to learn the languages spoken there. To be a Levantine means to depose your certainties and that sense of moral superiority that we often bring with us when we move somewhere else. It means to be ready to become a little like a chameleon, sometimes in a genuine way because you really want and have the tendency to adapt, in some other occasions because you eventually have to do it, as the condition of an ‘eternal foreigner’ often forces you to keep a low profile in order to be accepted by the locals, especially in times of political turmoil. In fact Levantines never stopped keeping an eye on what was happening around them, as this was of vital importance for them, both at an economical and existential level. They generally cultivated their strongest relations with the ones who were most similar to them, but at the same time they also used to keep good and intense relations with members of all the other communities, while learning something from all of them.

I think that all these values are still very actual and they define a sort of eternal ‘Levantine ethics’ that may be promoted and practiced as well in the contemporary world.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer

Brief bibliography:

Alimdar, Selçuk. Osmanlı’da Batı Müziği. İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları: Istanbul 2016

Aracı, Emre. Donizetti Paşa. Osmanlı Sarayının İtalyan Maestrosu. Yapı Kredi Yayınları: Istanbul 2006.

Baydar, Evren Kutlay. Osmanlı’nın Avrupalı Müzisyenleri. Kapı Yayınları: Istanbul 2010.

Kosal, Vedat. Western Classical Music in the Ottoman Empire. Istanbul Stock Exchange 2001

Santini, Gualtiero. Diario dell’assedio e difesa di Ancona nel 1849 [Diary of the siege and defense of Ancona in 1849]. Vecchioni: L’Aquila 1925

image 1 - Selvelli family’s registration entry in the Italian embassy in Constantinople

image 2 - Italo Selvelli’s Palermo conservatory diploma from 1881

image 3 - Italo Selvelli’s Marche Triomphale, 1897

image 4 - Italo Selvelli’s 1904 concert invitation

image 5 - Augusto Selvelli March pour Niyazi et Enver Bey 1908

image 6 - Augusto Selvelli March for the Ottoman constitution 1908

image 7 - Augusto Selvelli Vatan march 1908

image 8 - Italo Selvelli Resna march 1908

image 9 - Italo Selvelli Reşadiye march 1909

image 10 - The official Ottoman text from Sultan Reşat expressing gratitude for Italo Selvelli’s march in 1909

image 11 - The concert invitation for the benefit of Armenian victims of the Adana massacres 1909

image 12 - Italo Selvelli in Thessaloniki with Cemil bey and Zeki Osman Gungor

image 13 - Luigi and Oscar Selvelli listed in a theatre play programme, March 1912

image 14 - The Selvelli family tomb in the Feriköy Catholic cemetery

Italo Selvelli with wife (Anna Maria nee Pussich) and children around 1905: left: Antonio (b. 1896), down: Carlotta (b. 1900), up: Maria Elda (b. 1902), right: Luigi (b. 1891). Photo probably taken in the family residence in Yeşilköy (San Stefano).

Guido Selvelli (on left) with stepmother Maria Zellich and friend in Bomonti (beer garden next to a large Swiss Levantine brewery in Şişli district) 1924. The other child is Wilfrid Pussich (born 1913-1914).