The Interviewees

Raphael Cormack

Interview

1- You submitted and passed your phd in 2017. What was the title of this thesis?

Yes, the title of my thesis was Oedipus on the Nile: translations and adaptations of Sophocles’ Oedipus Tyrannos in Egypt, 1900-1970. It looked at several different 20th century Egyptian versions of the play, arguing that Egyptians used the ancient text to think through questions of power, leadership and statecraft worked in their contemporary context. It also looked at the many different ways that Egyptian intellectuals at the time viewed their Ancient Greek heritage (as something to be proud of and emulate, or as a colonial imposition).

2- You have concentrated your research, with a future book publication, on the 1920s – 1930s theatre and night entertainment scene of Cairo. What were the reasons for this narrow focus? Do you think including other cosmopolitan ports such as Alexandria and Beirut would have diffused the subject matter too much to allow for an in-depth view?

Part of the reason for my focus on Cairo is a corrective one. The cosmopolitan history of port towns like Alexandria, Smyrna, Salonica etc. has long be discussed. I wanted to show that Cairo has an equally (perhaps more) diverse and interesting history. The focus is also driven by the contours of the Arabic entertainment industry. Cairo was probably the major centre of the Arab entertainment industry at the time. People came from all over the Arab world to make it as stars in Cairo and performers from Cairo frequently toured across the Middle East (as I discuss in the book). Talking about Cairene entertainers allows you to talk about the whole region. That is my defence at least! But, of course, if I had the space and time it would be fascinating to also compare Cairo with Alexandria and Beirut as well as other places like Baghdad, Damascus, Jerusalem, Tunis even non-Arab speaking places in the Eastern Mediterranean like Istanbul or Athens.

3- Would you define ‘multiculturalism’ more of an ethnic diversity in a place and time or do you think the overarching consideration is the interaction of native and imported cultures in discrete environments, such as the night scene of Cairo at the time?

For me, the interesting thing about multiculturalism is not simply that it exists but how it works and how people interact with each other. In the world of entertainment in 1920s and 1930s Cairo, we can see this happening at close quarters. It was messy at times and I don’t want to give the idea that Cairo in the 1920s and 1930s was a paradise of co-existence. There were certainly prejudices but people still managed to work through these or in spite of them and create some fascinating work. There is often a drive to create a simple and unified history of a National culture but the truth is usually more complicated. Performance in 20th century Egypt has a huge number of influences from traditional farces and shadow plays with comic stock characters, which had been performed for centuries, through modern French vaudeville and beyond. I want to celebrate the mess, not try to hide it. That is what multiculturalism means to me.

4- In your former blog you mentioned ‘On 22nd April 1910 in Cairo, 6 women came together for an unprecedented performance at the Egyptian Theatre: an all-female performance of a play called “The Passion of Kings” (Gharam al-Muluk). On 4th May a critic in the newspaper al-Mahrusa wrote a long note on the event, describing his reaction.’ Clearly local Arabic / European newspapers are one of your chief sources of information. Was there a degree of shock and scandal in these reports where Muslim sensibilities were challenged by local women performing for the public as they would have done in contemporary Western Europe? Would you go further and state these women were the vanguard of a feminist emancipation of Arab women though clearly later developments would eclipse any gains they made and presumably even their names are not recalled today?

In the late 19th century the issue of women on stage was a complicated one. There was very little opposition to acting on an Islamic basis (There is no evidence behind the common suggestion that some Muslims were opposed to acting because it was a form of representation) but it was not seen as a respectable thing for women to do. In these early days of European style theatre in Egypt some female parts were played by young boys and others by Jewish and (Syrian) Christian women. However, by 1910, when this all-female troupe appeared on stage, it was seen as a curiosity but not a scandalous one. The reviewer, though, may have been showing some of his prejudices when he criticised the weak acting of the troupe. He was ready to see women on stage but may not have been ready to take them seriously.

The women who first appeared on the stage as actresses from the 1870s onwards were clearly hugely important as was the creation of a short-lived all female troupe in the 1910s. They did pave the way for females stars and actresses who came later, though they have been largely forgotten. Whether these women were a feminist vanguard is a harder question to answer. What I want to do with my forthcoming book is not to say that these actresses created Egyptian feminism but that they did play a part in the female liberation movement, one which is often overlooked.

5- The ‘rise of feminism’ in Egypt, which is your research focus covers a contemporaneous time with a similar struggle by Suffragettes in Britain and elsewhere. Do you think women who ran theatres and dance halls etc. could be considered to be a proof of this empowerment or could it be that the dangerous perceived link between this art and vice / alcohol / gambling acted as a ceiling on these gains by a conservative society? It appears the British were not interested in this emancipation as the women got the vote in Egypt only in 1956.

Again, the very important question of whether we should call these female performers in Egypt feminists. I believe that we can but we need to raise a few caveats first. These women were working within a system, often a very misogynist one, rather than changing it. Individual singers and entertainers at the time managed to win considerable power and independence but it is unclear how far it spread to other women. That would take other more systemic advances (like the winning of the vote in 1956, the institution of compulsory female entertainment etc.). Still, female troupe leaders like Mounira al-Mahdiyya and cabaret owners like Badia Masabni, were important for many reasons. The biggest of these is that they were given a voice and allowed to talk about issues that affected them: male exploitation, patriarchal marriage etc. Reading through interviews in the 1920s and 1930s, female entertainers are given space to talk about issues that affected all women. The most striking of all of these might be Fatima al-Sirri, a woman who had a child with a member of Cairo’s elite, which he subsequently refused to support. She spend years in the courts suing for the right to have the child legally recognised as his and eventually won. During the course of this she gave countless interviews in the press and her case was widely publicised, turning this one case into a representation of something larger.

These actresses were only part of a movement, one that could be dismissed by conservatives as debauched and immoral if they wanted, but they allowed these important discussions to be had.

As part of a feminist history they are also extremely important examples of non-elite women fighting for a satisfying life in a world where that was often difficult.

6- It seems the interwar / 1940s was a bit of a ‘belle époque’ for Cairo with a lot of colourful characters passing through and some staying for the long-term for example Eric de Nemès, the Hungarian Illustrator in Cairo. He clearly was very talented and very prolific yet, his origins remain enigmatic. With so many strands to cover, is it difficult for you to try to trace individuals from history, perhaps in this case through Hungarian / Jewish records? Nemès appears to have stayed in Egypt post the 1952 revolution. How big was this group of Europeans and when this this mini cosmopolitan scene finally fade for good?

It is often said that the cosmopolitanism of the Egypt’s “Liberal Age” came to an end with Nasser in the 1950s. I don’t want to deny that because it is largely true but I am interested in the character of Eric de Nemès because he offers some different ways to think about it. He was an illustrator who began to make his name in the 1940s, famously working with the Art and Liberty group of surrealist artists. Not much is known about his background. He was originally Hungarian and may have been Jewish (There are Hungarian Jews called Nemes but there is little evidence about Eric de Nemes himself). Unlike most Europeans, he did not leave after Nasser came to power and he later resurfaced in the historical record working with Maya Angelou and others at the Arab Observer.

Eric de Nemes is curious, partly because he is a European who stayed in Egypt but also because he also becomes part of a different, kind of cosmopolitanism in the 1950s and 1960s in Egypt, which has only recently begun to receive attention: African cosmopolitanism. In the 1950s and 1960s Cairo was home to a large number of African liberation movements (from the well established to the fly by night) as well as a growing number of African Americans, seeking relief from the situation in the USA. Work by Hisham Aidi and others had started to show that there was a different kind of cosmopolitanism in Cairo at the time, which Eric de Nemes saw first-hand. There is still a large Sub-Saharan African population in Cairo with a cosmopolitanism of its own.

This does not mean that nothing was lost in the 1950s, it was. But Cairo has never been a mono-cultural city and it is not that today.

7- We have European actors in the Cairo scene as well in the Arabic language. Isaac Dickson was a dance trainer and worked in films and he is rather enigmatic as there is very little you can find about him? Presumably the consular archives are held in London can give some clues, but are there any other archives you could consult, such as old trade directories, embassy, police records etc.

Isaac Dickson, who trained two of the most important dancers in mid 20th century Egypt, Samia Gamal and Tahia Carioca, like Eric de Nemes is another person we know tragically little about. I might also add to that list a personal favourite of mine, Dolly Smith, an English woman who led several important dance troupes in the 1920s but who we know very little about. These are the kind of people who are left out of Nationalist histories because they are not “Egyptian” enough and are left out of other histories because they worked mostly with Arabic speaking Egyptians. After 1956, Dickson falls out of the historical record. I have looked in the consular archives in London but found nothing. There were so many people in the city at the time that people only tend to enter the records there if they die, commit a crime, divorce or go mad. So we need to be a little creative. Someone at the Levantine Heritage Association talk suggested consulting old trade directories, which is a good idea and I am intending to do it. Otherwise, one can hope that things like newspaper articles, memoirs and other archives might help.

8- Would you welcome some members in our circle to contact you with possible leads and ephemera to assist you?

Of course! Information is so hard to find about these things and it is often scattered across the world in libraries, archives and private collections. Any possible leads are always welcome. The more resources the better.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer, March 2019.

Josephine Baker in Cairo in the 1930s.

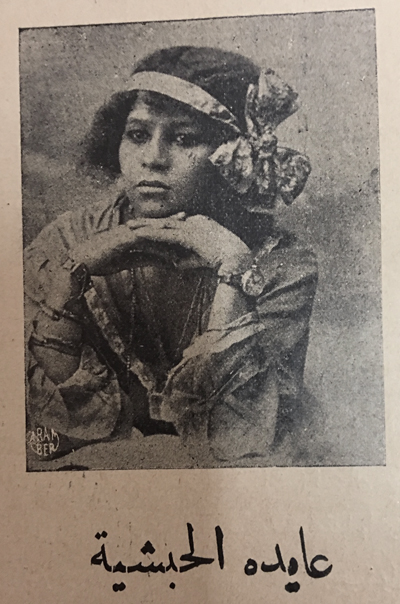

Ethiopian (?) actress Aida al-Habashiyya from al-Titatru Magazine, 1924.

First female theatrical troupe leader in Egypt from Mohammed Taymour’s 1922 book; Hayatuna al-Tamthiliyya.

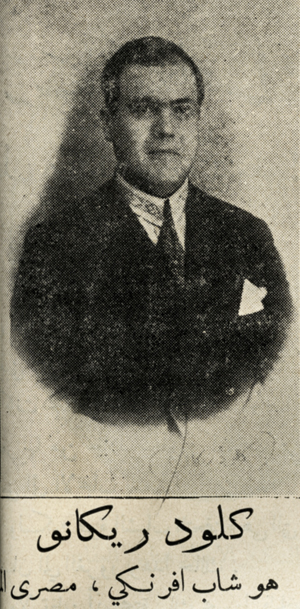

French (?) actor Claude Ricano from al-Masrah Magazine 1926.

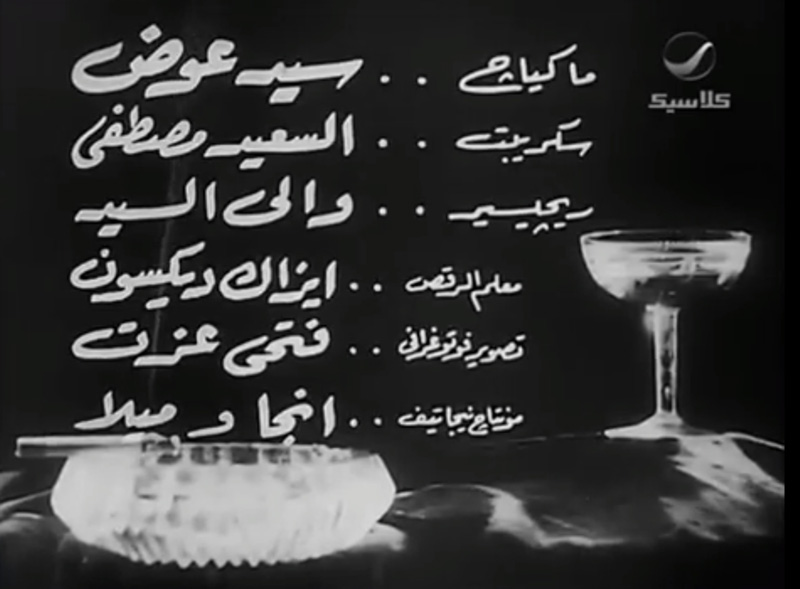

One of the credits that include Isaac Dickson.