The Interviewees

Interview with Philip Mansel, March 2025

1- In March 1821 a declaration encyclical letter was issued by the Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople and many Orthodox bishops under him condemning the invasion of the Ottoman Empire by rebels from Odessa and the early moves for Greek independence, with highly insulting language directed to these insurrections. Do you think this was truly heartfelt by the high echelons of the Greek community in the Ottoman capital or was it real-politic as anything less in terms of showing their total loyalty to the state would mean they would lose their heads?

I think, like many politicians at all times the Patriarch and the Bishops probably had 2 policies and 2 attitudes even within themselves and their hearts and minds. On the one hand they were extreme conservatives, hated revolution and innovation and feared Ottoman reprisals leading to the massacre of thousands of Greeks. On the other hand some Bishops and maybe the Patriarch himself may have had at certain moments sympathy with and knowledge of the Phiikel-Hetaireia.

2- In March 1821 the (ex)Greek Patriarch Gregory V despite this encyclical did get hanged by the order of the Sultan Mahmut II for not ‘controlling his flock’. Yet Mahmut II was the first of a line of Western leaning pro-reformists who would 5 years later liquidate the Janissaries. Was Mahmut II using these symbolic heads as scapegoats for his and his army’s failure to contain the rebellion and thus take the heat off him from an angry Muslim populace, thus was it a ‘damage control’ exercise?

It is hard to know the precise motives of the Sultan. Among them were rage and a feeling of betrayal and the feeling that the Patriarch was responsible, because he came from the Peloponnese where part of the revolt had started. Also the Sultan used his reprisals as a way of seizing the fortunes of certain prominent Greeks.

3- The Ottoman Empire always had a multitude of minorities, such as Sephardic Jews from 1492 and from earlier eras Greek Orthodox and Armenian Gregorian, as well as Catholic Levantines and a multitude of slaves of different ethnicities captured by corsairs. Of all this mixture was it natural for the Greek Orthodox community to be the most trusted by Ottomans, to such an extent that they were elevated to high office as prince of Wallachia or Moldavia or servants of the Porte?

Yes, it was completely natural for the Greeks to be serving the Ottoman Empire. They were everywhere from Trabzon to Corfu, on the whole they were suspicious of Western powers and they had skills of great use to the Ottomans: naval, commercial, diplomatic, linguistic and medical. Some had been educated at the University of Padua. Many genuinely believed that the preservation of the Ottoman Empire favoured the Greeks and their religion.

4- How was the Second Phanar as you define it in the 19th century different in style and influence to the Phanar in the 18th century?

The second Phanar is a term I prefer to the more usual ‘neo-Phanariots’ who sound too much like neo platonists or too close an imitation of the original Phanariots. The second Phanar had closer links with the Palace, fewer links with Wallachia and Moldavia and was distinguished by constant use of the French language. Members of the second Phanar reached very high positions, for example that of Ottoman ambassador in London when British friendship was crucial; and under Abdulhamit II Greeks in the palace included the Sultan’s banker (Giorgios Zarifi); his doctor (Spyridon Mavrogeni); his architect (Nikolo Vasilaki) and his carpenter (Kallinicos). It was a golden age of Greek – Ottoman relations, cemented by shared hostility to the rising power of Bulgaria. In 1877 the Patriarch issued encyclicals praying for Ottoman victory over Russia.

5- By 1900 the Greek Orthodox population of Constantinople was 236,000 amounting to 25% of the city, so there was a steady rise through the 19th century brought about by Ottoman tolerance and encouragement to settle there. Do you think one of the causes of this was the creation by that community of a new merchant and industrial class, similar to that created by the Levantines of Smyrna?

Yes, I think the key was economic prosperity and boom conditions. We had the talk by Richard Calvocoressi in 2024 which showed that his ancestor despite having been enslaved after 1822, nevertheless chose to return and live in Constantinople. Things can’t have been too bad. Also the community through its schools, hospitals and churches provided a fully Greek life for the Greeks of the capital. On the other hand, some Greek officials feared that Istanbul Greeks were adopting foreign manners and languages.

6- Ottoman Muslim education presumably was based on Koranic teaching mostly with the emphasis on languages helping them to understand their scriptures better, like Arabic and to a lesser extent Persian. This is where presumably the Greek and French schools where the Greek upper classes also went had an edge in terms of learning European languages. Was this one of the main reasons why Greeks also become some of the ambassadors to the Empire?

Yes, it was a very important reason. Though some Ottoman viziers spoke perfect French such as Ali and Fuat Pashas.

7- Theodore Kasap was a famous Greek Orthodox journalist who moved between Constantinople and Paris. He was multi-lingual and rebellious yet ended up in the employ of Abdulhamit II in Yildiz Palace. Did people like Kasap represent examples of what could be a truly equal Ottoman empire for the Orthodox community, which later soured with the rise of the Young Turks; and could history have been different had nationalism not been so ferocious?

History could have been different if government leaders had a different outlook. Nationalism was becoming more, but never totally, dominant before the Young Turks. For example in the Greek-Ottoman war of 1897 many Greeks openly left Constantinople in order to fight against Turkey in the Greek army as some did again in the Balkan war of 1912. Nationalism dominated but nevertheless Constantinople, Vienna, Paris and St Petersburg remained multi-national capitals. St Petersburg had a mosque before London or Paris.

8- You mentioned in your talk the prominent Ottoman Greek banker Yorgo Zarifi’s grandson’s memoirs. How illuminating are these in terms of laying out the power dynamics between the Greeks and the Ottoman state in the period?

They are the only source I know in English or French which shows the sumptuous way of life of the richest Greeks of Constantinople before 1914. They appear very confident and clearly enjoyed summers at Tarabya and Prinkipo with parties, yachts and so on. References to Ottoman Sultans accept them as providing a useful framework for their existence. On the other hand they condemn Abdulhamit II for the massacre of Armenians and record Abdulmecit’s love of the bottle. Clearly the second Phanar had different expectations before 1912 or 1914 than subsequently. They were businessmen and the Ottoman Empire appeared to be a reliable investment – more reliable than the kingdom of Greece, which was often bankrupt.

9- The small island of Samos rose up in revolt in 1822 but unlike nearby Chios which also joined the rebellion, there was no bloodletting on that island and Samos was allowed autonomy under a series of Phanariot princes as governors. Do you think this was a diplomatic move not done not out of goodwill to those islanders but to take away the sting from the excesses that took place in Chios which was virtually depopulated by Ottoman troops. Did Samos materially benefit from this new status in terms of benefactory works commissioned by the Phanariot governors?

I have not been to Samos and I cannot find much about it. But clearly having your own Prince, Government and assembly could lead to good works and investment in the island. What is interesting about the principality of Samos that it implies a different attitude to government and statehood, fostering regionalism over nationalism, as had been the case before 1821.

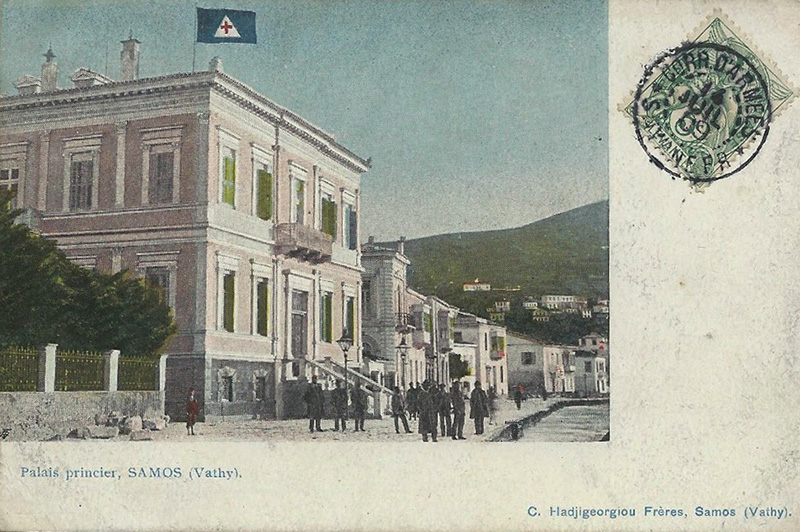

Postcard image of Lycurgue Ist [?], one of the Phanariot Prince of Samos. Below image of the Palace building in Samos.

10- With the Balkan wars and the growth of the Greek state that included Salonica and region in 1912 were some of these Phanariot families then seen as traitors by either the Greek state or segments of the Ottoman Greek community?

Some Phanariots were always considered as traitors even before 1821. There was always a division between the Greeks of Istanbul and those of the young Greek state. Different mentalities and way of life.

11- Konstantinos Mousouros was Ottoman ambassador in London for 35 years (1850-1885). So this would cover multiple reigns. Though this ambassador was clearly capable do you think the Ottoman state wasn’t particularly interested in training new diplomats as it had other priorities and was happy for these Greek career diplomats to perform that role until they were no longer fit due to age and often replaced from the Phanariot community, as his son Stephanos would later also became ambassador in London as well?

There were capable Ottoman Muslim diplomats but the Porte felt a Christian would be more popular in London.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer - read interviews from 2011 and 2024.