The Interviewees

Herve Georgelin | Pelin Böke | Alex Baltazzi | Axel Corlu | Philip Mansel | Antony Wynn | Fortunato Maresia | Vjeran Kursar | Christine Lindner | Frank Castiglione | Clifford Endres | Zeynep Cebeci Suvari | Sadık Uşaklıgil | İlhan Pınar | Ümit Eser | Bugra Poyraz | Oğuz Aydemir

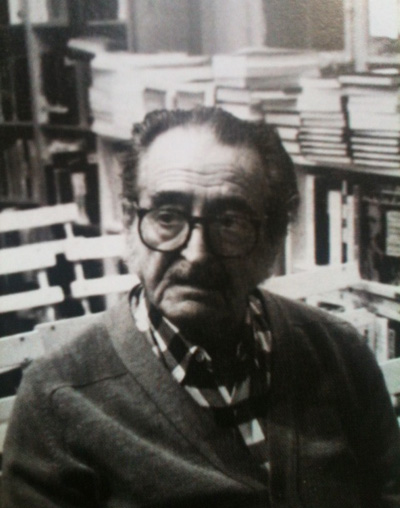

Interview with Clifford Endres on Eduard Roditi, October 2015

1- Can you tell us how you first came across the writings of Edouard Roditi and why you found them of particular interest?

I first discovered Edouard Roditi in Mediterraneennes 10 (1997), an issue subtitled “Istanbul, un monde pluriel” and devoted to the City. John Ash, the British poet (one of whose poems was in the issue), had been exclaiming how the Roditi piece, “The Vampires of Istanbul,” was alone worth the price of the journal. So I bought it, and he was right: although “Vampires” had been shortened, as I later learned, by about a third from its original publication in The Delights of Turkey (New Directions, 1977), it remained a hilarious satire, acutely on target as regards Turkish pride and prejudice in the Istanbul of the 1960s.

I then looked up Roditi’s work as a surrealist poet in the Paris of the late 1920s. It’s great stuff. He wrote in both French and English, and at age eighteen was publishing in transition — the avant-garde journal published in Paris — while enjoying the attention of luminaries such as Leon-Paul Fargue and T.S. Eliot, from whom he learned a good deal. In the 1930s he began to discover his Jewish roots (his parents had never gone in much for religion) and his poetry took a turn toward the more traditional, as in Prison Within Prison: Three Elegies on Hebrew Themes, published in 1941. He translated Andre Breton into English for View magazine in 1946, wrote a brilliant biography of Oscar Wilde (1947), and published a volume of poems in 1949 with New Directions. Two volumes of art criticism — Dialogues on Art and More Diaogues on Art — were published in the sixties and continue to be reprinted. And there’s more, much more. As a literary man we might say his most important influences were Francophone surrealism, Anglophone modernism, and Hebraic traditionalism; whatever they are, his work should be better known than it is.

2- So what is the connection between this Paris writer and Istanbul, and how did you follow it up?

Of course I wondered how Roditi had obtained his obviously well informed knowledge of Istanbul, a city far away from Paris both geographically and culturally. And then about this time I picked up Yashar Kemal’s Mehmet, My Hawk, published in 1961, and found Roditi’s name on the title page as translator. Well, this was something! So I contacted Yashar Bey, who turned out to be full of stories about Edouard, which he narrated with gusto. He sent me on to Şakir Eczacıbaşı, who had been good friends with Roditi. It was Şakir Bey who filled me in on the avant-garde scene of 1950s and ‘60s Istanbul and Roditi’s contributions and adventures therein.

It emerged that Roditi’s family possessed deep roots in Constantinople and the Levant and that Edouard had been vaguely but not seriously aware of these while growing up in Paris. His grandmother had him read the Greek newspapers to her, for example, and his father enjoyed taking him to an Armenian cafe where people spoke Turkish. But his first visit to Istanbul came only in 1950, when he happened to be in the country interpreting at an international WHO congress in Ankara. There he looked up Thilda Serrero, a relative who belonged to both the Sephardic and the literary communities. Thilda would later marry Yashar Kemal. (“Kemal,” incidentally, was Yashar’s pen name; his family name was Gökçeli, which gave rise to a bit of confusion before Edouard realized who Thilda’s new husband really was.)

3- The reference books call Roditi an “American writer.” Do you think he would be comfortable with this designation?

Although he was born in France (in 1910) and did not set foot in the U.S. until the age of nineteen, Edouard was always conscious of himself as an American citizen—even if “home” was France. After a couple of shorter trips, he came to the U.S. in 1938 to attend graduate school at the University of Chicago, but the war overtook him and he never finished his PhD. Despite this — or perhaps because of it — in later years he taught at U.S. institutions like Bard College, San Franciso State, and Antioch. Around 1939-1940 he wrote a remarkable long poem called “Cassandra’s Dream” that eerily foretells the terrible changes lying in wait for Europe and her Jews. His friend Ammiel Alcalay quotes from it in his book on the Levant, After Jews and Arabs: Remaking Levantine Culture. During World War II he made broadcasts in French for the Voice of America from New York, where his mother had an apartment and where he spent the war years. From there he also worked hard to save the lives of a number of people stuck in Nazi-occupied France. He returned to Paris in 1946 and in fact ran into difficulties with the French authorities in the 1950s because, while he also considered himself quite French enough, he’d never applied for citizenship.

4- Didn’t he work as a professional interpreter and translator?

He was in fact a legendary translator and interpreter who could converse in ten or twelve languages and do simultaneous interpretation among several of them. He worked at the Nuremberg trials and charter meetings of the United Nations, and is nowadays the subject of articles by scholars of translation studies. He did it for a living; although his grandfather had amassed considerable wealth in the nineteenth century, his father lost most of it in the stock market crash of ’29, and Edouard had always to think about making ends meet. This fact helps to explain the large number of reviews and newspaper articles that he cranked out, sometimes almost mechanically, while complaining that they took him away from his literary work. Incidentally, he felt that his phenomenal language abilities were perhaps connected with the epilepsy that afflicted him for much of his life.

5- What do we know about Roditi’s family history in Constantinople and the Levant?

Edouard’s grandparents married in 1866 in the Kuzguncuk synagogue on the Asian side of Constantinople (though their homes were in Hasköy, on the European side). The marriage continued a tradition of union between Romaniot (Judeo-Greek speaking) and Sephardic (Judeo-Spanish speaking) Jews. Roditi says in his memoirs that his surname derives from the island of Rhodes, from which the Byzantine (Romaniot) Jews were expelled by the Knights of St. John in the fourteenth century. Among the female line of his ancestors he lists the Gallipoliti and Belinfante families; the Greek and Spanish names are obvious clues to the way Jewish populations of the Levant have mingled. It’s also interesting that Edouard’s grandfather obtained Tuscan citizenship in the year of his marriage, registering at the Italian consulate as David di Nissim D’Israele Roditi. This was not uncommon: the patriarchs of the well-known Camondo family — to which the Roditis are distantly related — similarly held Italian citizenship while serving as bankers to the Sultan. Moreover, the Roditis seem always to have been interested in literature: as early as 1660 Simon Roditi was active in Smyrna as a publisher of Ladino and Hebrew books. In the nineteenth century Benjamin Roditi, again in Smyrna, published an edition of the Me’am Lo’ez with financial assistance from Abraham Camondo. And in Cairo Moussa Roditi published some beautiful books in French around 1900.

6- Edouard Roditi’s father was evidently an accomplished enginer, who was charged with building the Pera Palace Hotel. Tell us about that.

Edouard’s father Oscar was born in Constantinople and spent his early childhood there. He acquired American citizenship when the family moved to Boston in the 1870s. When they then moved to Paris he obtained a good French education and found employment with the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits et de Grande Express Européen, which operated the Orient Express. He was attached to the board of directors and held responsibility for building and managing first-class hotels for Orient Express passengers. One of these was the Pera Palace in Constantinople. Oscar supervised its construction and looked after it for some years afterward. Edouard reports that his father was in town during the Armenian massacre of 1905, when Migirdiç Tokatlian, owner of the rival Tokatlian Hotel, contacted him with an urgent plea for help. Oscar’s position was such that he was immediately able to charter a ship and by nightfall evacuate about two hundred members of the city’s leading Armenian families safely to Egypt. Among these was a young Calouste Gulbenkian, who many years later told Edouard, “Your father saved the lives of most of my family in Constantinople”. Oscar seems not to have returned to the city after marrying in 1907.

7. What do we know about Roditi’s mother?

The short answer is, “Not very much”. Edouard has described his mother’s family background as “discordantly mixed”. Her own mother—Edouard’s maternal grandmother—was a French girl from a partly Flemish family from northern France; her father was a German Jew from Hamburg named Waldheim. She gave birth to Edouard’s mother in France; but a year later, after the birth of a second child—a still-born son—she abandoned daughter and Jewish husband both, withdrawing to a convent that was also a psychiatric home. Edouard’s grandfather then took his young daughter to London where she was brought up by an aunt. The girl grew up thinking of herself as an English child; in adult life she resisted both her French and American citizenship. Conflicted as to whether she was Catholic or Jewish or Protestant and preferring to speak only English, she had little liking for her husband’s polyglot crew of Levantine relatives. Edouard in later life believed that the emotional trauma suffered by his mother as a child was transmitted to some extent to her own children, particularly him.

8- Can you hazard a guess as to why Edouard Roditi is not better known today, in Turkey and abroad?

Well, he certainly should be better known internationally than he is. One reason he isn’t is that, as may be the case with many Levantine notables, he falls outside the usual nationalistic categories. The French think of him as an English writer, while the English think of him as a French writer, and the Americans don’t know quite what to think. In Turkey he may not be a household name, but he is well remembered by artists and writers of the mid-century avant-garde. As Şakir Eczacıbaşı noted, he contributed significantly to the development of modern Turkish culture. For example he championed Turkish art and literature in numerous European publications; he enabled Turkish artists such as Yüksel Arslan to get to Europe and get their art shown; he was a facilitator between the community of Turkish artists in exile in Paris and those back here; he and Derek Patmore almost singlehandedly saw to it that Turkish art was shown to the world at the Edinburgh Festival of 1957; and he was instrumental in the establishment of the first Turkish cinematheque in 1963—which led directly to the IKSV festivals that we enjoy today. So he is quite well known to those who are left of that pioneering generation.

9- Among his works, which do you think might be most worthy of being reprinted?

I think it would be laudable for a major publisher to bring out a broad compendium of his work so that readers could experience the scope and depth of his writing firsthand—poetry, essays, art criticism, travel writing, all of it. For that matter there are quite a few articles and over a thousand pages of memoirs still unpublished. The memoirs alone would qualify as an important historical document of twentieth-century Europe.

10- Do you know what might have happened to Roditi’s library, papers, and art collection after his death in 1992?

The largest archive of Roditi’s work is at the Charles E. Young Research Library of UCLA—85 linear feet of material!—with smaller but interesting collections elsewhere, such as at the Humanities Research Center at UT Austin. Regarding his extraordinary art collection, some of it was left to the Musee Juif and some to the L’Institute du Monde Arabe, both in Paris, while most of the rest was bought by Michael Neal at auction in 1999. Neal, based in France, has collected Roditi material since 1978 and has about 3000 items including books, articles, carbon copies, and unpublished typescripts. He’s in the process of establishing an Edouard Roditi web site, which will be very useful to scholars and aficionados when it is finished. Meanwhile he can be contacted at (https://michaelnealbooks.wordpress.com)

11- Istanbul has had some very respected American institutions, many going back decades, one of which is the American Research Institute of Turkey, whose funding by U.S. authorities has, I believe, recently been severely cut. Do you think it would be a tragedy for the city to lose this institution?

ARIT, The American Research Institute in Turkey? The short answer is: Yes! It would indeed be tragic for scholars of Byzantine, Ottoman, and Republican history to lose this institution and its extremely useful libraries and facilities in Istanbul and Ankara.

12- Do you have a personal project, not necessarily to do with the Roditi legacy, for the future that you would like to tell us about?

Yes, I’ve lately been delving into the history of Fener (old Phanar) and Balat on the Golden Horn, pursuing my interest in the archaeology of “lost Istanbul,” to borrow John Freely’s phrase. I hope that a nice little book will emerge from this.

Earlier work: Edouard Roditi and the Istanbul Avant-Garde - Clifford Endres, Texas Studies in Literature and Language, Vol. 54, No. 4, Winter 2012, 471-49

Interview conducted by Craig Encer, October 2015.

To contact the interviewee clifforden[at]gmail.com