The Interviewees

Herve Georgelin | Pelin Böke | Alex Baltazzi | Axel Corlu | Philip Mansel | Antony Wynn | Fortunato Maresia | Vjeran Kursar | Christine Lindner | Frank Castiglione | Clifford Endres | Zeynep Cebeci Suvari | Sadık Uşaklıgil | İlhan Pınar | Ümit Eser | Bugra Poyraz | Oğuz Aydemir

Interview with Antony Wynn, author of Three Camels to Smyrna, June 2012

1- What was the fascination for you with Turkey and Iran? Is it a family legacy?

My grandfather served in Turkey after WWI. He was General Marshall-Cornwall, who after WWI occupied a senior position in the army of occupation in Turkey. Among other things, he was responsible for delineating the border with Bulgaria. In WWII he accompanied Churchill on his visit to, having previously advised Churchill that the Turks would not, and should not, be persuaded to abandon their neutrality and join the Allies. Churchill would not listen to him and ordered him to make the attempt which, thankfully for Turkey, came to nothing. Churchill’s repeated blandishments were met by a series of judiciously diplomatic failures of İnönü’s hearing aid.

2- You clearly studied Sir Percy Sykes in great detail, including going to the places he went to in Iran. What set him apart from other adventurers / diplomats / European merchants operating in the same geography at the time.

He was unusual in that he took particular trouble to learn the local language and study the history, and in that he stayed in Iran for nearly 25 years, whereas his contemporary colleagues spent only a short time in the country.

3- Did you fall in love with Iran the first time you visited it, or was it a gradual process of acclimatization? Where would you recommend the intrepid visitor should not miss?

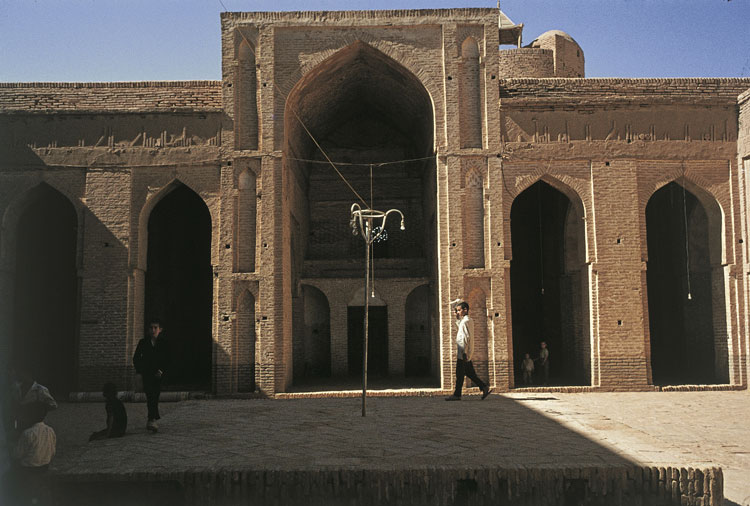

Everyone is bowled over by Iran on the first visit. The intrepid visitor should go to Zavareh, on the edge of the central desert, to see an early Seljuq mosque, a jewel of brickwork and stucco.

4- Did you visit Iran before being offered a job there? What was your connection with the OCM boss Brian Huffner?

I had spent 9 months at Shiraz University. I joined OCM after seeing an advertisement in The Times as I was about to graduate from Oxford.

5- In 1976 you moved to Northern Iran to run a country racecourse in the Turkoman border country. Why such an unlikely location and was horse-riding one of your passions? Later you moved to manage the newly established Teheran race-course, were you recognised for your talents and ‘head-hunted’?

Not at all an unlikely location! The Turkoman live only for their horses. A Hong Kong – Australian joint venture had a project to establish horse racing in Tehran, with Australian horses, jockeys, trainers etc all flown in. The Iranians wanted the Turkoman to be able to participate, which meant that somebody had to go and interest them in racing to Jockey Club Rules. No Australian was keen to spend two years in that part of the country, so they asked me to do the job. I am a horseman of sorts and had read a few Dick Francis books, so was ahead of the Turkoman on Jockey Club Rules!

6- You had to leave in a hurry like all other foreigners when the Iranian Revolution swept in December 1978. How was the atmosphere like, a mixture of elation and horrors of what may come? Did you sense something like this was in the air when you were in the countryside?

No, we did not have to leave in a hurry. We never felt threatened by the revolution and it was made very clear to us that the revolutionaries had no quarrel with us, but only with the Shah and all his works. We went home for Christmas, fully expecting to return after the break, revolution or no revolution. Our flats and properties were well looked after by the local Revolutionary Committee and nothing was touched. The company eventually decided to pull out for commercial reasons.

At the time, there was a feeling of elation at the change to come. Only the wise old heads had any idea of what the revolution would turn into, but nobody wanted to listen to them.

7- Do you still visit Iran, do you still have any business dealings with the country? You must still have special friends out there.

I went back regularly on business every year until the sanctions made business impossible.

8- What prompted to you to write ‘Three Camels to Smyrna’. Were you given access to the company records?

Bryan Huffner asked me to write the OCM history. I told him that a plain company history would be of very limited interest, but a history of Turkey, Persia, North India and Afghanistan as witnessed by the OCM people might make a good story. There are plenty of books about carpets, but none about the people who made them and what happened to them. He had a very jumbled collection of company records in his attic, which took a lot of sorting through. I was greatly helped by Brian Giraud in Izmir, who made his family records available to me, and also by the city archivist in Izmir and the history department in Izmir’s 9 Eylül University.

9- Clearly the European bosses of the OCM concern were shrewd and calculating businessmen. Do you think the system was one of exploitation of the weavers or did they provide new markets for goods that would otherwise mostly be for a very limited internal market.

It depends on what you mean by exploitation. All workers are exploited by their employers to some extent, in order to give returns to the shareholders. Exploited or not, village people queued up to be employed and vast numbers, maybe 80,000 in Turkey alone, were working for the OCM, which was the second biggest single employer in Turkey after the railways, at one point. Without the OCM’s ability to raise finance in Europe, there would have been no work for these people.

10- The rival carpet firms agreed to merge to form the OCM in 1907. Was this a brave decision of relinquishing individual sovereignty for the common good, or was the possibility of a price war too hard to contemplate that forced their hands you think?

From the records it is quite clear that they were all cutting each other’s commercial throats before the merger and the only way out was to get together. It took some time for these ‘very individual individuals’ to get used to working together!

11- Remarkable men appear in the scene concluding remarkable deals, such the American Charles Fritz who through a series of happy accidents became the sole monopoly holder of Anatolia wool. Were these Westerners completely attuned to the twists and turns and vagaries of Ottoman politics and intrigues and able to hedge bets to ensure they would gain an advantage over rivals, and in this extreme case, cut them out altogether. Was it more a symptom of a weakness of the ruling system of cronyism or were these merchants extremely well informed, read and connected?

Without the system of capitulations, which meant that the Levantines paid virtually no taxes to the Ottoman government, the Europeans could not have competed with the local merchants. Of course, anyone in business at the time had to have good relations with the authorities, then as now. The biggest advantage that the OCM had was its ability to raise finance from European banks and investors. With the Ottoman debt, this was impossible for the local traders.

12- Why did the Gördes / Uşak region become such an important carpet producing region? After all OCM and its earlier versions had looms set up right across Anatolia.

These two places were important long before OCM came on the scent. As demand increased, weaving started further east.

13- Post the 1923 population exchange the weavers, dyers, washers etc. of these carpets were now mostly refugees in Greece, yet the OCM attempt at re-instating these people with new looms in Greece seems to have failed. Was it a case of lack of local infrastructure in the improvised Greece or was the system of production and movement too indexed to Anatolia to make this Aegean jump?

There were all sorts of problems: lack of raw materials and skilled labour for one, but principally the fiscal setup discouraged trade.

14- The style of managing affairs seems to have differed in these earlier companies, with the Bakers seeming to work to a great range of catalogue of designs, while the La Fontaine Company seems to have concentrated on mass production without always managing their affairs of supply and demand as efficiently. Do you think the OCM merger also helped bring all these individual strengths together?

The whole point of the merger was to pool the best resources of each of the members – design, dyeing, spinning and marketing.

15- Cecil Edwards was amongst the pioneers in setting up the OCM operations in Iran in 1911 when the country was struggling not to be swallowed up by giant neighbours, and so was precarious. Do you think Edwards was also a remarkable man of study?

Edwards, and his remarkable wife Clara, were amateur scholars of the best sort. Clara was a great letter writer and one day I hope that someone will produce an edited version of her letters home, which give vivid accounts of rural life in Iran during those troubled times.

16- The OCM struggled as a concern right up to the 1980s. With better management, do you think the contraction could have been managed and the final debacle avoided?

I was not with the company at that time, so cannot say. I think that the traditional carpet business was doomed anyway, as cheap production in Pakistan, China etc, together with better communication, made it easy for local producers to deal directly with the market in Europe and USA and cut out the wholesale importers.

17- Do you have future projects in the pipeline?

I hope one day to be able to write the ultimate travel book about Iran, but will have to wait until the situation improves.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer, 2012

Sir Percy Sykes

Zavareh mosque, Seljuk-era mosque built 1135-1136, making it the first known dated mosque constructed according to a four-portico (iwan) plan in the post-Islamic Iran.

Carpet weavers in Iran, Qajar Era.

The standard transport for carpets across Anatolia.