The Interviewees

Herve Georgelin | Pelin Böke | Alex Baltazzi | Axel Corlu | Philip Mansel | Antony Wynn | Fortunato Maresia | Vjeran Kursar | Christine Lindner | Frank Castiglione | Clifford Endres | Zeynep Cebeci Suvari | Sadık Uşaklıgil | İlhan Pınar | Ümit Eser | Bugra Poyraz | Oğuz Aydemir

Interview with Vjeran Kursar, April 2015

1- How did your interest in history start and in particular your interest in Croatians in the Ottoman Empire?

I became interested in history as a school kid, although I did not think that would be my profession as an adult; I guess this is a bit too an abstract occupation to choose at an early age. Later on I developed interest in what was at the time was called “Oriental studies”, nowadays a somewhat an inappropriate term and the combination of the two led to me to the study of Ottoman history. Ottoman studies were fairly neglected in Croatia as a field until recently, despite the fact that Croatian history is closely intertwined with the Ottomans until the 18th century in the case of the territory of modern Croatia, or until 1878, if Bosnian Catholics, i.e., Croatian people living in Bosnia are taken into consideration. The situation has started to change since 1994 when the Department of Turkish Studies was established at Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of University of Zagreb by Professor of Turkish language Ekrem Čaušević, and Professor of Ottoman History Nenad Moačanin. Since I am personally one of its first graduates who studied Turkish Studies together with History as a joint program, the choice came quite naturally.

2- To put things in a historical perspective Croatians were for centuries on the front-line of Ottoman lands so no doubt also suffered privations from the wars and incursions that took place on their soil. However did ‘real-politics’ play a part in ensuring a stable border, such as tributes, bribes and slaves play a part in ensuring the vulnerable coast such as Dubrovnik were allowed to remain free?

The Ottoman conquest caused great demographic, political, cultural and confessional changes in the region. Great parts of the territory of the Kingdom of Hungary and Croatia, and Croatian lands in particular, were lost to the Ottoman Empire during the 15th and the 16th centuries. The rest of Croatia, which accepted the Habsburg dynasty as its rulers, was shrunk up to less than a third of its former territory and became known as reliquiae reliquiarum, “the rest of the rest”. Dalmatia, the coastal part of today’s Croatia, witnessed a similar fate. Territory that was not conquered by the Ottomans, consisting of coastal towns, a very thin strip of hinterland and islands, was ruled by the Republic of Venice.

For the contemporaries, the arrival of the Ottomans represented a trauma. Land that remained unoccupied was looted by infamous akıncıs and other local troops, often even in times of peace. High numbers of Croatian slaves mentioned by local chroniclers are confirmed in Ottoman sources as well. Slaves of Croatian origin were abundant in Istanbul, while many peasant serfs from Croatia and Bosnia were forcefully deported deep into Ottoman territories in the eastern Balkans, and sometimes even Anatolia. In such an atmosphere, the remaining parts of Croatia saw themselves as antemurale Christianitatis, “the bulwark of Christianity”, and acquired a military border character.

Without undermining the negative aspects of Croatian experience with the Ottomans, the myth of eternal total war and absolute enmity needs to be re-examined. The wars, undoubtedly devastating and tragic, in fact represented only a fragment of Croatian-Ottoman shared history. During the often lengthy periods of peace, international trade and opportunities of amassing wealth by taking part in it, were attracting both sides to cooperate across religious lines and state borders. Even during times of war trans-border trade did not entirely stop, but was adopting a clandestine character of smuggling. In the 19th century, however, the situation thoroughly changed; when the reformed Ottoman Empire opened its market and borders to foreign capital, experts and workers, and great numbers of Croatians started to migrate into its big cities, above all Istanbul, in search for jobs and business opportunities.

The best sense for ‘real-politics’ was shown by the mercantile town-state, the Republic of Dubrovnik (Ragusa), which, well aware of the impossibility to militarily oppose the Ottoman Empire, accepted its nominal suzerainty in the 15th century, and, as a Sultan’s vassal, gained privileged access to its market, and became one of the main intermediaries between East and West, with colonies of its merchants across the Balkans. Owing to this lucrative trade, Dubrovnik and its merchants amassed great wealth and experienced a period of progress in the 16th century, while Ragusan general prosperity lasted until the last quarter of the 17th century.

Another example of a good sense for ‘real-politics’ is the appeasement of Bosnian Franciscans by the Ottomans following the conquest of Bosnia in 1463. Faced with the choice of either suicidal opposition to the new ruler, which would have inevitably resulted in the extinction of Catholicism in Bosnia, or acceptance of the fate and recognition of Ottoman rule that would have guaranteed its survival, the Franciscans decided on the latter. Thus, they were granted basic rights in accordance with sharia regulations. According to modern human rights standards, sharia based restrictions imposed on non-Muslims would seem discriminatory. In the pre-modern world where general intolerance towards minorities was the rule, however, the Ottoman design represented at least a basis for survival and preservation of individual identity. In reality, from time to time wise and able Catholic elites managed to slightly stretch this narrow framework in order to meet the vital needs of the community. The 19th century as the age of reforms brought removal of restrictions and offered new opportunities to peoples of the Empire, which the Bosnian Franciscans were ready to grasp. They managed to renovate old and build new churches and monasteries, as well as schools, throughout Bosnia. In addition, the Bosnian Franciscans even bought the old Catholic church of St. George in Galata in 1853, which served as the permanent residence for their representatives in the Ottoman capital, as well as the spiritual centre for Croatian and Bosnian Catholic immigrants until 1882.

3- You were one of the writers for the documentary film “Croatians on the Bosphorus” (Hrvati na Bosporu) and in 2011 “Zelic- Printers to the Empire”. How were these productions received by both the public and historians in Croatia? Was there much awareness before of this somewhat successful population?

The documentaries “Croatians on the Bosphorus”, whose script I wrote together with Vesna Miović, an expert on Ragusan history and the author of the book on Ragusan diplomats in Istanbul, and “Zelić – Printers to the Empire,” which I wrote alone, deal with a little known history of Croatian diaspora in the East, i.e., the Ottoman Empire. The story of forgotten Croatian migrations to Istanbul and the success of some of the migrants in the capital of the Ottoman Empire provoked a great public interest in Croatia, and since the premiere on national television in 2011, these were broadcast again at least six times. The documentaries were well accepted by historians as well, and I am glad that they have incited a couple of younger colleagues to start research in that direction.

4- How good are the Croatian historical archives in relation to Ottoman era studies?

Croatia has several historical archives that have collections of Ottoman documents of prime importance for the history of the region. The most famous is the collection known as Acta Turcica at the State Archive of Dubrovnik, which holds about 15.000 items. It contains documents issued by sultans and local Ottoman authorities in neighbouring provinces, which regulated Ragusan trade in the Ottoman Empire, the position of expatriate Ragusan merchants, taxes, etc., in the period from the mid-15th to the early 19th centuries.

The Venetian Dragoman archive of the State Archive in Zadar is the second most important collection of Ottoman documents in Croatia. It covers the period from the 16th to the late 18th centuries, and contains the correspondence between Venetian authorities in Dalmatia and Ottoman authorities in Bosnia, Herzegovina and Montenegro. It holds close to 4.000 documents dealing mainly with diplomatic relations as well as trans-border issues, such as trade, smuggling, theft, crime, etc.

In addition to the two above-mentioned historical archives, another important collection is that of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts in Zagreb. Its Oriental Collection founded in 1927 consists of 2.100 Ottoman manuscripts and 760 archival documents, which were acquired from private collections in Bosnia, Herzegovina, Kosovo, Serbia and Macedonia by the famous German Ottomanist Franz Babinger, who headed the Collection between 1927 and 1928, and by his successor, the Russian Orientalist Aleksei Olesnicki, who remained in charge of the Collection until his premature death in 1943.

5- How did you establish contact with the descendants of the Zellich family members in Croatia? How helpful were they?

During first couple of months after I discovered several late 19th – early 20th centuries postcards published by the Zellich print house in one of Istanbul’s antiquarian book-shops, which incited me to study its history, I was not able to locate a single member of the Istanbul’s branch of the family. Then, resigned after numerous unsuccessful attempts, I tried my chances at Facebook, and, surprisingly enough, found a group called “Zelic is my family name and my roots are from Brela-Makarska, Croatia”. There I saw old photographs of the the family in Istanbul, and immediately contacted the creator of the group, Mr. Edwin Zellitch from Athens. After I informed him of the Croatian Television documentary project “Croatians on the Bosphorus”, Mr. Zellitch kindly granted me access to his family archive, and we interviewed him in Athens. Thanks to Mr. Zellitch, the story started to unfold, and, via his kind assistance, I connected with other members of the family who kindly shared items from their family archives with me, like Mr. Željko Zelić from Brela, Croatia, Mr. Jean Zellich from Paris, and Mr. Mario Augusto Zelic and Mr. Marco Antonio Zelic from Sao Paolo, Brasil. Their help was crucial in realizing the documentary projects, as well as my forthcoming article on the history of the Zellich print house in Istanbul.

6- How much did you find to what extent Croatians benefitted from capitulations provided to the more powerful Western nations of France, Britain etc. or was it a half-measure accorded as they were foreign Catholics so effectively under French over-arching protection?

In general, Croatians were under the protection of capitulations provided to the states whose subjects they were. Thus, inhabitants of the Republic of Dubrovnik enjoyed its protection as confirmed in the ahdnames (capitulations) of Dubrovnik, people of Venetian ruled Dalmatia enjoyed the protection based on the Venetian capitulations, while inhabitants of historical Croatia and Slavonia that were under the Habsburg rule (continental parts of the Republic of Croatia), enjoyed the rights based on the Habsburgs’ capitulations. After 1815, following the congress of Vienna, which granted Dalmatian and Ragusan territories occupied by Napoleon to Austria, people of Dalmatia and Dubrovnik came under the Habsburg protection as well.

In addition, as other Catholics in the Ottoman Empire, Croatians could have counted on French protection in general.

The protection of above mentioned powers was on occasions conferred upon Bosnian Catholics as well, who were in fact Ottoman subjects, but were, when need be, diplomatically assisted by Ragusan, Venetian, Austrian, or French representatives at the Porte, particularly in religious affairs.

7- What made the Zellich family particularly successful among the various printing establishments operating at the time in Istanbul?

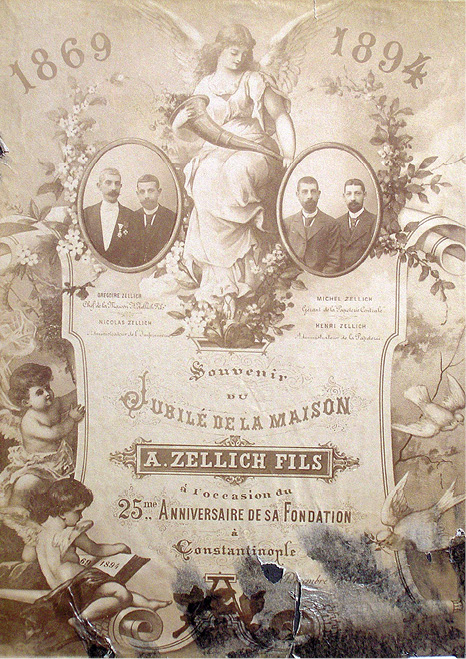

The founder of the Istanbul’s branch of the family, Antonio Zellich, started the printer’s career as the assistant of Henri Cayol, the person who introduced the new printing technique of lithography into the Ottoman Empire. After Cayol’s death Zellich continued the business, and soon afterwards founded his own print house in 1869. His sons joined him later on, while one of them, Grégoire Zellich, mastered the art of lithography along with “Oriental languages”, meaning probably Ottoman Turkish, Persian, and Arabic, the main languages of the Ottoman intelligentsia, as prerequisites for future success. The family was publishing in various languages and scripts, including Ottoman Turkish in Arabic script, French, Italian, English, German, and Croatian in Latin, Greek, Serbian, Russian, and Bulgarian in Cyrillic, as well as Armenian. They published several journals and newspapers, various official publications, numerous books, as well as graphic and pictorial material of superb quality, including the famous postcards with motives of Istanbul. The print house received numerous international and domestic rewards and recognitions.

8- Did the family diversify its operations either in different cities or occupations?

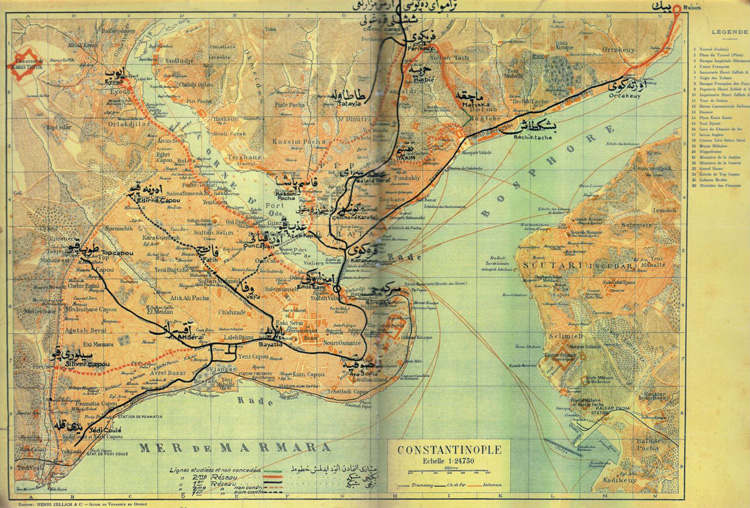

The Zellich family was acting as an importer of lithographic and printing material and machines and was representative of several European and American companies in the Ottoman Empire. In this manner the family helped in establishing and equipping several other print houses in Istanbul and one in Trabzon. In addition to the print house, the family owned two stationers shops, one in Beyoǧlu in today’s İstiklal street, and the other in Galata.

9- When did the final Zellich members return or die out in the city?

It seems that members of the family started to leave Istanbul in the 1930’s due to economic and political crisis in the country. Mr. Edwin Zellitch and his family, for example, left the city in the 1970’s. Today there is only one family living in Istanbul, that of Mario Zeliç. Other members are nowadays living in Greece, France, Spain, and Brasil, but they remain in contact, periodically visit Istanbul, and keep the tradition of the famous Stamboul printers alive.

10- Your recent research interest and subject of a talk in Istanbul has been ‘Ragusans in Edirne: Diplomatic, Religious and Economic Presence’. Why do you think Ragusans had a presence in the relatively marginal city of Edirne? Did they have their own church in this city?

Contrary to the common opinion, the conquest of Constantonople in 1453 and transfer of the court in the following years did not mean that Edirne lost all of its former imperial importance. It continued to be the second most important city of the Empire in which sultans often resided during the 16th and especially the 17th centuries. As an occasional centre of political power and host to the court, Edirne attracted foreign diplomats, including the Ragusans. As one of the major centres of the Balkan trades, Edirne attracted Ragusan merchants as well, who were present in the city especially in the 16th and the 17th centuries. In addition, Edirne was one of the stops along the road to Istanbul for Ragusan envoys who carried the yearly tribute of Dubrovnik to the Sultan. In order to suit the needs of envoys, the Republic of Dubrovnik maintained a residence in the city from the mid-16th century onwards, if not earlier. In addition to the residence, there was a chapel that served the spiritual needs of diplomats and other Ragusans, as well as the wider Catholic “Latin” community, being the only Catholic church in the city.

In the 17th century the existence of the church and the residential complex brought about a series of litigations which lasted over a century, ranging from petitions for the church to be repaired, to disputes with the Muslim and Jewish neighbours. The dispute over the chapel and residence in Edirne correlated with quarrels the Ragusans had in other Balkan towns with competing local merchants, such as Orthodox Serbs and Bulgarians, Muslims, and even co-religious Bosnian Catholics, indicating that the cause of Edirne’s dispute was probably not only mere confessional bigotry, but mercantile rivalry.

At the beginning of the 18th century the residence and church burned down in a great fire and despite the efforts of the Ragusan diplomats, were not rebuilt.

You will be able to read about this topic in detail in an article of mine that will be published in a new book on Edirne edited by Birgit Krawietz and Florian Riedler forthcoming later this year.

11- Do you have future projects you would like to divulge to us?

As co-editor, I am preparing a volume on the Republic of Dubrovnik as a vassal state of the Ottoman Empire with my colleague Domagoj Madunić. In addition to the Croatian translation of several selected articles from the recently published book “The European Tributary States of the Ottoman Empire in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries” edited by Gabor Karman and Lovro Kunčević, it will contain four new articles on different aspects of Ragusan-Ottoman relations.

I am also writing a book on the position of non-Muslims in early modern Ottoman Bosnia, which represents the main field of my research. I will try to bring to light different experiences of life under the Ottomans of three Bosnian non-Muslim communities - Catholics, Orthodox Christians, and Jews, based on material from Istanbul and largely under-utilised Bosnian archives.

In addition, I am participating in a project entitled “Evliya Chelebi and Croats: New Perspectives” under the leadership of Professor Nenad Moačanin, which will result in a new translation of the parts of the famous 17th-century Ottoman travelogue concerning Croatian lands, as well as in several additional studies of different aspects of history of the region and its population.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer, April 2015.