The Interviewees

Interview with Emiliano Bugatti, January 2019

1- In 2006, you enrolled in the PhD program at the University of Genoa, and you completed your dissertation on the urban and architectural identity of Smyrna and Salonica in 2009. Both these cities were major ports in the Ottoman Empire with substantial ethnic mixture topped by a rich European population that directed a lot of that commerce. So clearly development wise there were many parallels, however amongst the differences would be Salonica was the smaller port with a less dominant ‘Levantine’ community. Did these subtle differences manifest themselves in the extent of the architectural transformations in these two cities?

I think we should consider the big Jewish Sephardi community of Salonica as an active Levantine actor in the stage of the city modernization, even if they were not properly Levantines. About the transformation of both cities, there are obviously differences but, and this is the core of my PhD dissertation, there were very similar processes, even the same actors and at the end results in the urban space. It was the nationalization of a plural environment which changes the shape and the social structures of these cities irreparably.

2- In 2010, with TEGET (Istanbul) you won the Izmir Opera house competition and in 2011 you were mentioned for the rehabilitation project of the Lalla place in the Medina of Fez, Morocco. Can you tell us more of these projects, your vision that clearly captured the imagination of the selection committee and the chances that these projects will be realised in the future?

Izmir Opera House was probably the most important architectural competition in Turkey of the last twenty years. The project in Morocco was an incredible opportunity to propose at the urban level an idea of rehabilitation of a type of city that I studied for years. I think, as always in architectural competitions it is important to stress the concept of the proposal, and both projects had strong ideas. For Izmir, a movement of the “soil” that created a space-building which can be a public space in all of its parts, not only on the inside. Indeed, every meter of the given plot was preserved for the public; the roof as a giant terrace with functions and accesses to the structure. Not a box or an abstract form, a shape which defines a huge public area. After we won, I did not work on the construction drawings. My wife was involved in this important phase and she was fundamental in submitting thousands of drawings, and after almost eight years the project has not changed but has improved and detailed and it will be built in the next few years. Like in Izmir, with the project in Fez, we imagined to create at the centre of the given site a huge courtyard that we called “Le Grand Fondouk” completely covered with wooden panels designed to filter the light according to the angle of the sun. It was an extremely brave proposal but in this case the jury decided to reward the more feasible ones.

3- What fascinates you about the architecture and urban fabric of the Eastern Mediterranean?

The pluralism and the eclecticism. It is matter of cultural synthesis or even conflicts but results, in many cases, the defined original solutions and a formal richness which was still vibrant in the first half of twentieth century. Unfortunately, today it is very rare to find in the same region such beauty and richness.

4- Amongst the various buildings you have observed and analysed in the Levant, do you have a favourite and do you have a building that is in danger of loss through neglect that authorities should do more to preserve?

I think there are many anonymous Levantine buildings which are neglected and public institutions, like municipalities, leave the responsibility of their preservation only to the owners, who are often not in the economical condition to take care about these structures. But there are cases which are particularly serious like the D’Aronco heritage in Istanbul, and in this case responsibilities involves the Italian Republic in the case of the Italian Summer residence of the Embassy.

5- Clearly every building served a need for a designated community and trade in its time and buildings outlive people and communities when they move away for various reasons and often the newcomers do not view the building in the same way as its layout doesn’t fit in with their needs. There is clearly a tension of needs versus architectural integrity when adjustments are made. Do you think part of the architects remit should be compromise in terms of allowing for change to prevent total loss? Do you think part of the training for architects should be the balancing act of practicality versus preservation? Can you think of a good example where such a compromise has saved a building?

I believed that is in any case better for a building to be used, even with some losses, instead of being abandoned. I used to live in Beyoğlu in Levantine apartment buildings which deserve more attentions from the inhabitants but this is an issue which can be very dangerous if the only solution offered is to transform that sector of the city to a hotel district. It is necessary for a public debate about the physical and immaterial values involving the many actors and people living in these areas. Han Tumertekin did a great job for both the SALT cultural centres in Istanbul, but it is the less problematic part of the story. More complex is the issue of the historical housing and I think on this issue the good intensions of architects is not enough.

6- Both Izmir and Salonica at the end of their Ottoman period suffered a catastrophic fire accompanied by a loss of a huge segment of their minority populations. Do you think using emotive languages such as ‘catastrophe’ then creates in our mind an impossible nostalgia of loss on all levels to then denigrate future development as mostly regressive and perhaps even ignore that such ‘catastrophes’ were a regular feature in all these crowded mostly wooden construction Levantine cities. Do you think architects can thus fall prey to this brutal dichotomy of inherent value of pre and post fire buildings?

What I tried to explain in my writings is that fires were not the only elements of the catastrophe. They were in the late-Ottoman period the reconstruction after fires which allowed for the modernization of many Ottoman cities. The point is also when social and political structures changed these events determined the occasion to delete and to re-write urban-architectural identities. Architects and academics are doing the job to investigates these events but it is necessary to design an attitude to pass this trauma and eventually find a new balance.

7- You have done work on the Kampos region architecture of Chios, Greece. This was an affluent zone of the multi-cultural elite on the island, but were they truly ‘multi-cultural’ both in terms of their own culture or architectural representation? Do you think the words such as ‘multiculturalism’ and ‘Levantine’ can be double edged swords where they can explain some concepts but get in the way of defining other cultural aspects?

The Kampos of Chios was my first experience of research within a multi-cultural context. I was able to do this study thanks to my mentor professor Maurice Cerasi when I was at the end of my Masters in Genova. I would like to invite readers to discover Cerasi as a sharp intellectual throughout many papers of him that can be easily accessed on the internet. Cerasi detested the word ‘multi-cultural’, because it is not enough to define every cultural element and the richness we have in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. I completely agree with him that multi-cultural is not an undefined mix of shapes and tastes. It is a more complex overlapping, synthesis of many cultural and physical components. We need more words and definitions to define and control more this complexity, imagine how vast the concept of “Arabic” is to define the identity of a building or an urban fabric.

8- Most analysis of urban transformation of Istanbul in the 19th and 20th centuries concentrates in the Levantine zones of Galata and Beyoğlu, but in your 2009 project you concentrated on Divanyolu within the zone of Fatih in old Istanbul, yet directed by foreign advisors. Do you think there are inherent differences in approach and consequence when rigid European vision urban designs are enacted in zones where totally different socio-economic groups interact and do you think there are lessons to be learnt today from ‘top-down’ interventions?

When I worked on the Divanyolu topic, with Maurice Cerasi, we wanted to point out how multiculturalism is not always good for the city scape. Indeed the main street of the Ottoman government, Divanyolu, was designated in the centuries not following any western pattern and in the 19th century it was reformed with the aim to transform this space into a boulevard. The conflict between the pre-existing types and the idea of the boulevard is even today not solved and probably won’t be solved in the future. Multiculturalism is about ideas and not only about agents, and of course Italian architects like Barborini, worked there but the point was another; to explain how some ideas are not easy to insert in some context, as the historical peninsula of Istanbul often demonstrates.

9- I guess the perennial problem for the affluent Levantine merchants who occupied zones near ports was dealing with the clutter of buildings and humanity occupying their zone from centuries before and trying to regulate and move them in a way to facilitate trade. Have you analysed how this was achieved while still maintaining social harmony as these Europeans were a small minority even in these zones and needed the lower classes to do the various tasks in these ports? Do you thus get an impression just how much ‘state capture’ was achieved by these merchants and their diplomatic representatives in the latter stages of the Ottoman Empire?

It is an interesting idea of research but I have not explored yet...

10- One of the defining features of the architecture of the Ottoman port cities are the ‘Hans’ which served both as offices and warehouses often in multiple occupancy. So defining a building as a ‘single use’ becomes redundant and often the occupiers would be short-term tenants and so the building would change in overall function over time and today many in Galata etc. are now converted to luxury hotels. Do you think there is a scope for creating a database of not just the building history but detailed occupation history to help better understand the dynamics of these neighbourhoods?

Yes, of course, but I am looking at the same problem from another perspective, the flexibility of these buildings allowed many changes of uses and I am not surprised that today many became hotels. With this kind of flexibility of types we can easily understand how the neighbourhoods have changed. On the contrary to go back to the Divanyolu case study, there, the Ottoman religious buildings, mosques and mausoleums, are not so flexible to alter their relation with the street space or to have new uses.

11- Walking in districts such as Beyoğlu one notices that even many domestic dwellings formerly occupied by the upper classes of the Ottoman society, dominated by Levantines, were highly ornate so not only would these buildings cost more to erect but foreign materials and workmen had to be imported. Why was it important for these communities to show off even when there would be no trade benefit?

I am not sure that even master builders were imported from Europe. As other scholars pointed out, i.e. Paolo Girardelli, architects, Levantines or Europeans were able to work with local workers. They were brilliant in creating western buildings that preserved many features of the traditional ones because of the persistence of some techniques and actors as master builders. Identity is the key word to understand that non-Muslim Ottomans, even those from low-middle class, wanted somehow to show the new tastes introduced from Europe. I remember during a visit in the east of Anatolia that we found small shops with very interesting westernisation displayed through their ornate architectural elements.

12- Do you think considering the richness of architectural heritage out there, is there enough study dedicated on this legacy and in your opinion just how vulnerable is this fabric? Is there enough dialogue between students, professors, restorers and city planners in your assessment?

When I was student in Genoa, my professor in Town History, Ennio Poleggi, with his books affected the perception of the historical fabric and created the local conditions to preserve some areas or building as in the case of the Rolli palaces. I think in Turkey there is not enough communication between academicians and politicians, but this is a long and even sad topic.

13- The currently nearing completion Galataport project in Istanbul is massive in terms of scale of transformation of the traditional dockside of Galata and in terms of ambition to create a mega-cruise line terminal. Do you think the bigger the projects the bigger the need for outside investment and so the bigger the threat for the urban fabric of a zone which was built out of a long evolution of ‘organised chaos’ to coin a phrase?

Not necessary, it depends on many aspects and many actors involved in the project. In general, within these economic conditions it is difficult to impose for architects a vision which is only cultural oriented. As we know, profit is the main actor of the story and public municipalities should orient a collective and cultural goal for such projects. It is too early to judge and I don’t have enough information, not only me!, about this urban project.

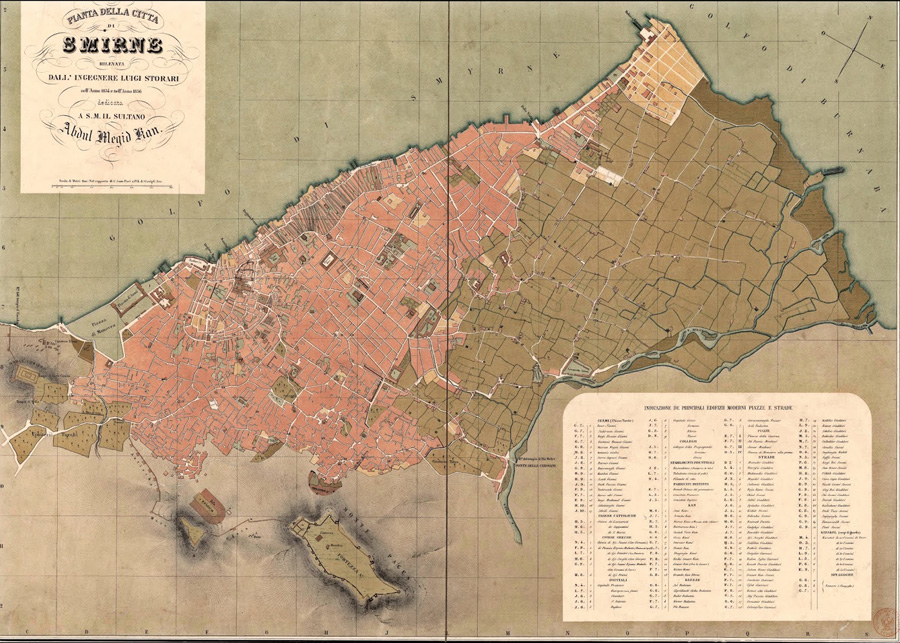

14- You recently published “The Contribution of Luigi Storari to the Analysis and Development of the Levantine Urban Fabric” for the forthcoming book “Design Across Borders: Italian architects and builders in the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey”. For the common man Storari is less well known than say Fossati brothers, Giulio Mongeri, Edoardo De Nari and other foreign architects who operated in the Ottoman realm. Can you give a brief highlight of Storari’s style and the buildings he designed and what attracted you to him?

Storari was an engineer and he worked on urban projects to rebuilt areas destroyed by fires in the mid of 19th century. He is not very well known but he did a great contribution to the soft reform of the traditional urban fabric, he imported the grid model of urban blocks in a very sensitive way to be colonized by Ottoman buildings. His model is very appreciated today in Kadıkoy and Fener, even when areas where rebuilt following his idea after his time proven plans.

15- What plans do you have for the future? Do you think the LHF could have a supporting role in any projects?

Recently, I worked with my colleague Elif Yurdaçalış on a paper about Kadınlar Pazarı, a market “square” in Istanbul Fatih district. The place was part of the çir çir fire reconstruction plan, it was realized as a stretch of a boulevard during the late-Ottoman period. In the twentieth the project was marginalized by the Prost plan and became with the migration from Eastern Anatolia after the 1960s a market. Even here we can find a very interesting conflict between western concepts and inhabitants practices. Curiously, the case study has not been considered very attractive by Istanbul universities, despite many departments we have not found recent text about it. At the highest level of my aspirations, I would like to work if I would be able to find a research grant on an Atlas of Levantine architectures to draw and explain to a wider audience the importance of this idea of buildings and urban fabric. Another project of mine is to work on the heritage left by my mentor Maurice Cerasi. It would be a great future asset to create an archive of diverse architectural materials and to discuss his incredible lessons, which I strongly believe has to be known by Turkish students and future architects.

Marginal to the Levantine research, but important for my Italian-Turkish relationship, Last summer I organized a Summer School in Italy that involved twenty Turkish students from four Istanbul universities. It was beautiful to bring together my former students in my new environment, Italy!

Interview conducted by Craig Encer

Architect and academic, Emiliano Bugatti’s research and work focuses on the architecture and urbanism of Eastern and Southern Mediterranean Basin, from the early modern period to the modernization of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. He collaborated from 2000 to 2005 with Maurice Cerasi at the University of Genoa (Italy) in academic research on the analysis and rehabilitation of historical cities in the Eastern Mediterranean Sea. In 2006, he enrolled in the PhD program at the University of Genoa, and he completed his dissertation on the urban and architectural identity of Smyrna and Salonica in 2009. He was Assistant Professor at the Department of Architecture, Yeditepe University (Istanbul-Turkey), between 2013-2016. In the last years, he has collaborated with architects and offices based in Genoa, Milan, and Istanbul. In 2010, with TEGET (Istanbul) he won the Izmir Opera house competition and in 2011 was mentioned for the rehabilitation project of the Lalla place in the Medina of Fez, Morocco.

The neglected Italian summer embassy building in Tarabya.

Divanyolu during the late 19th century.

Luigi Storari plan of Smyrna drawn between 1854 - 1856.

Some Levantine buildings in Pera / Beyoğlu.