The Interviewees

Interview with Achilleas Chatziconstantinou and George Poulimenos, March 2021

1- When did the idea of a book on the rather ambitious project of recreating and analyzing the Smyrna Quay pre-1922 come about?

AC: It was soon after we met each other, during the First Levantine Symposium in Izmir (2010), in which we both presented papers. Each of us had already spent many years researching aspects of the recent history of Smyrna (19th-20th c.), facing similar problems, mainly the lack of precise topographic data and the identification of image context. The choice of the Quay as our case-study was a quite obvious one, given that it was the most photographed part of the city, famous as well as essential in understanding its importance.

2- How did you set the limits of geography and time, so, for example, where was the south margin of the quay fixed and how far back from the frontage did you go? The Smyrna Quay was erected in 1875, and did you examine the more chaotic building-scape before and how difficult was it to trace building alterations till 1922? Would you contemplate widening any of these limits for a future volume?

AC: First and foremost the Smyrna Quay was an extraordinary technical achievement of its era and we had to address it as such. We researched all aspects of the construction project, including: design, milestones, blocking points, people involved as well as the various ways it transformed Smyrna and turned it into the most important Ottoman port. It also put an end to the pre-existing ‘chaotic’ as you called it urban environment, both architecturally and socio-economically. After the completion of the works, the city and its various functions would never be the same. Planning-wise, the Quay expanded the city as far as 50 meters towards the west and shaped a new waterfront by adding two main roads, the Quay and Rue Parallèle, tens of plots between them and two harbours. Its limits were the Aydin Railway Station at the northern end and the Imperial Barracks at the southern. However, since no accurate visual data further than the Punta tip (an area we call “the dark side of the moon”) has survived, that point was chosen as our start. The construction of the private and public edifices facing the waterfront was neither a simultaneous nor a fast process. Although the land use types on each of the Quay sections (Residential, Recreational, Commercial and Administrative) was more or less ‘fixed’ from the very beginning, some plots took several decades to be built up. So, in order to keep track of all the changes of just the waterfront buildings in space and time, we had to come up with a research methodology. This required the creation of an area map and the assignment of a unique ID to each plot and a number for each of its buildings. We utilized every available source we could find, such as images, maps, commercial guides, newspapers etc. Pre-fire 1922 was chosen as our reference year for drawing all existing building facades at that year, as accurately as possible. I would call the entire process a great adventure, by no means an easy one, which offered us many exciting moments. Regarding the possibility of a future volume, as long as new evidence keeps coming up, it is fair to say that, yes, several parts of the book contents would definitely need expansion.

3- You used a wide range of reference sources in Greece and abroad, including books, the press, commercial and travel guides, maps and images. How were you able to fix technical issues such as maps not lining up, very few of the images being square on and presumably a high bias in printed matter to more prominent buildings and businesses? Did you try to delve in further and try to find individual commercial occupancy in bigger buildings from clues such as sign-boards visible in postcards etc.?

GP: All these and many more were the problems that we had to tackle before drawing the facades of the Quay buildings. So, after drawing our own maps, developing a process of geometric ortho-rectification of photographs seemed the only way to proceed. Then we had to digitally stitch together the images and trace their main architectural features, along with features such as decorations, labels or any other visible evidence of its history. Soon enough, our ability to see things advanced so much that we were able to distinguish the tiniest of details or to read labels that were hardly visible. At the same time and while searching which company was located where, commercial guides or the press provided us with names that could potentially fit in those label frames and match their letters, in some cases narrowing down the candidates’ list to one.

4- The Quay seems to have been a microcosm of a truly multi-ethnic and multi-trade city where commercial properties such as hotels and warehouses, places of pleasure such as cafes were interspersed with personal dwellings, albeit of the higher levels of Smyrna society. Do you think calling this mixture ‘Levantine’ is also a misnomer in that clearly Greeks and other communities were also present in this trade interface, yet would you also argue that the skeleton on which they all acted clearly had a strong Western European vein and ultimately was designed to enrich a rather small European origin community?

AC: We must realize that back then the Levantines did NOT call themselves Levantines. This term was appointed later to a group of people bearing certain characteristics that best described them and their way of life and separated them from most members of the other local communities (Greeks, Armenians, Muslims and Jews). Moreover, using the term ‘Levantine’ instead of a national identity is in many cases far more convenient, given that mixed marriages among Christians of all denominations was a common practice. The strong Levantine presence on the Smyrna Quay clearly indicates their wealth and also the fact that they had invested in plots on the waterfront as soon as they were legally allowed to, many years before the construction begun. Greeks and Armenians also took advantage of the same momentum, the latter at a percentage far greater than what their population would hint. Muslim properties were also recorded but these followed a different pattern that had to do with their traditional place in the Ottoman society as landowners and so on, amplified by the immigration waves from the Balkans.

5- Were there some buildings and zones where collecting the information was especially challenging?

GP: The residential area was a quite challenging one, due to the fact that there were only two sources of ownership of private buildings: the 1889 plan of the Société des Quais and the Izmir Cadastre of 1936-37, both incomplete and distant from our reference year, 1922. So, unless we had other pieces of evidence to cross check them, it was quite impossible to accurately determine whether in the meantime properties had changed hands or not. We also faced difficulties in finding the exact location of several cafés that were only known to us from commercial guides, mainly because they used to change name, ownership and even spot too often, mostly along the Quay of course.

6- You recorded and sketched separately over 200 buildings. Why did you go to the extra effort in these architectural façade drawings? If you had the power to convince Izmir authorities, which building(s) in your opinion would be so symbolic that they would be worthy an in-situ reconstruction?

GP: Ever since we realized that a complete set of 1922 Quay images that would allow us to simply stitch them together and create a panorama did not exist, drawing the Quay building facades became our only option. In fact, we had to go through several failed attempts before we finally came up with a process that enabled us to produce a fairly accurate result. We are very proud for the completion of this project, a full reconstruction of the 1922 Smyrna Quay, which is something that has never been attempted before and we are sure that will be used as a future reference. There were many great buildings on the Quay, such as the Theatre of Smyrna, Grand Hotel Kraemer Palace and OCM (Oriental Carpet Manufacturers), so it is very hard to pick one that would be more emblematic than the others. Instead, I would encourage the Izmir authorities to do their best in preserving those still standing, i.e. the 14 full or partial survivors. There are also other ways to pay tribute to Smyrna/Izmir’s past, such as the one IZTO recently chose, by embedding architectural features of the Sporting Club to the facade of its new headquarters that were actually built on the exact same location.

7- The entire 1922 events Fire and ‘Catastrophe’ is still a highly political subject on both sides of the Aegean. Do you think your completely apolitical approach can help in more open exchanges in cross-border research and dispel the misconception that ‘all was lost’?

AC: An approach based on evidence and no speculations about important episodes of the city’s past that happened to have taken place on the Quay is quite political in my opinion. We hope that our reconstruction of the past of Smyrna Quay as well as our commitment to stay true to the facts as described in the sources, will allow younger generations of Greeks and Turks to learn the history of this metropolis, and also to come in terms with its glorious as well as turbulent past.

8- Other major trade ports in the Eastern Mediterranean also suffered disasters curtailing for good their prominence in commerce and imagination such as Salonica, Beirut and Alexandria. Why do you think Smyrna / Izmir has a special allure and yet tragedy about it, still felt almost century on?

AC: The catastrophe of Smyrna was the final chapter of the Greco-Turkish war (1919-1922), also known as the Asia Minor campaign. The war ended with the defeat of the Greek army, the death of hundreds of thousands and the expulsion of 1,5 million Greeks that fled to Greece, including my grandfathers and those of George. The humanitarian crisis affected the lives of millions, and, almost a century later, has not been forgotten. Moreover, events such as the Great Smyrna Fire and its causes are still disputed and raise tensions.

9- Port interfaces always have the problems of handling capacity, spare space and water depth. Clearly Smyrna suffered from all of these and how does your research show how these challenges to ease efficient export were solved or not?

AC: Smyrna became a major trading hub only after two major infrastructures had been developed: the railway and the port. These complemented one another and boosted imports and exports to unprecedented levels. From the middle of the 19th century onwards, new warehouses, factories, ‘locals’ and hotels were built, mainly triggered by this commerce. Needless to say, Smyrna was already ‘a city of hans’ above anything else, as early as the 17th century, so its importance was well-established. From May to October when trade was at its peak, even the quay road was occupied by all sorts of products that could not be kept in warehouses and the Gulf of Smyrna served as a natural harbour for those ships that were too big to dock into the inner port. Unfortunately, World War I and the Great Fire in September 1922 brought Smyrna’s growth to an abrupt end and the city never truly recovered from the blow.

10- How strongly was the Quay regulated in terms of restrictions placed on those who wished to expand seawards by way of jetties etc.? Do you find in the records disputes over land and tenure between quarrelling neighbours and who would be the arbitrator?

AC: Part of the very idea behind the Quay was to put an end to the chaos along the seashore that pre-existed as a result of capitulations. The quay construction works and new regulations affected more or less everybody, so the project faced fierce resistance from land owners, traders, port guilds etc. It is fair to admit that it would not have been finished had the Société des Quais not being given ‘extra powers’ through the concession and unless all sides had reached a compromise.

11- Clearly the story of the buildings is also one of families and investors both local and international. Did you also take on board tracing the story of these families, such as the owners of Kraemer Palace / Huck Hotel, who could be described as ‘late arrival Levantines’ and the source of their investments?

GP: Of course! Our research included all families and individuals present one way or another on the Smyrna Quay between 1875 (end of construction) and 1922 or even afterwards. It was quite fascinating to follow their lives, both in the private and the public sphere. Although several Europeans that settled in Smyrna during that period had not centuries-old roots in the East and most of them had to emigrate soon afterwards, they still left a very strong mark on the city.

12- The Ottoman Empire was not a colony of a Western Power yet in zones such as the Smyrna Quay, operations were run on a semi-colonial basis where the various stages of agricultural produce, carpets etc. production, transport and conveyance were under the control of mostly Levantines. Did your research detect tensions arising from the state based in distant Constantinople trying to alter the in-balance in their participation caused by the twin factors of capitulation privileges and dealing with Levantines who fully understood the strengths and weaknesses of the system?

AC: Based on the privileges granted to them by capitulations, the Levantines and Greek or Armenian protégés developed Smyrna and its economy, mainly through exploiting the various resources of its vast hinterland. Most of these entrepreneurs had agencies, trade houses or limited companies that competed with one another or made alliances and merged through intermarriages. Their enormous wealth reflected upon their way of life and the mansions they built on the Quay. The State was depending on them in order to collect its nominal share of the concessions’ profits and pay the foreign creditors, so in peace times it scarcely intervened in favour of a party, allowing them to run their own business. In fact, the absence of tight central control over local affairs is mainly responsible for ‘Gavur İzmir’, the city’s nickname.

13- What surprised you most while doing the research on this subject?

AC: I was surprised by the many phases that certain parts of the quay went through between 1875 and 1922! For example, images of the port area depicting the same plots five or ten years apart, may look totally different. This is yet another proof that Smyrna was a booming place but you can imagine what a nightmare it was to identify and date them. I believe our task was similar to that of the field archaeologists.

14- Are you looking for sponsors to publish this book in other languages such as English and Turkish?

AC: Yes, our next goal is to publish an English edition of the Smyrna Quay that would allow us to reach an international audience, including the Levantines and those linked with the Ottoman Empire and the Middle East, such as the Kraemers. Our goal is the English edition to be published by 2022, the 100 years anniversary of the Great Smyrna Fire.

15- Are you still researching this subject?

GP: There is always room for further research and we have no intention to quit, especially after being awarded the Academy of Athens prize for best history publication in 2019 for the Smyrna Quay! In fact, as we previously said, we have already found new evidence that will be presented in the next edition. We sincerely hope that our work will encourage more people to share their knowledge with us, allowing us to add additional missing pieces to the Smyrna Quay puzzle.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer

The Smyrna Quay book official link is here:

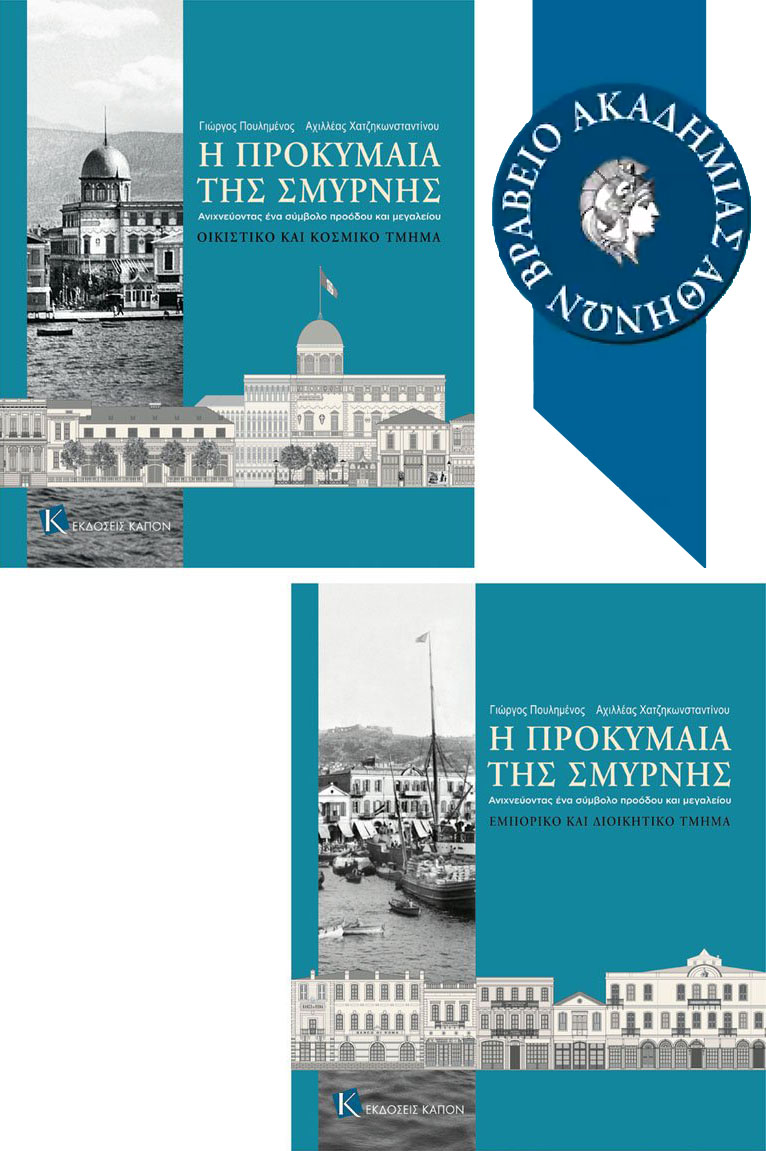

Book cover.

View of the Smyrna Quay on 9th September 1922 showing the arrival of the Turkish cavalry riding past abandoned belongings of Greek refugees who had earlier crowded the dock-side. Buildings in the background from right: Agence Maritime d’Orient / Ellerman lines offices, the Oriental Carpet Manufacturers exhibition warehouse and offices (moved to London post-fire), National Bank of Turkey / British Trade Corporation, Standard Oil Co. offices, Aegean Sea & Karaburnu hotel, Paterson warehouse (formerly also a steam mill, see chimney). The latter was full of flour at the time, which was instrumental in feeding the refugees after the fire. The two visible buildings at both ends were spared the fire destruction but do not stand today. To offer a degree of perceived diplomatic protection most buildings had foreign flags flying: The Ellerman lines a red British Naval flag, OCM a white version of this flag, British Trade Corporation a British flag, Standard Oil Co. an American flag and the Paterson warehouse a flag that cannot be distinguished in this image. This row of buildings is depicted below in architectural rendering: