The Legacies

Architectural heritage | Literature | Fine arts

| Music | Sports | Intellectual life

Here the term ‘Levantine’ is used in its broadest sense as none of these famed artists were born in Turkey and only a few died there. However they all spent a considerable part of their lives in the Levant and their legacy is associated with that of the Levant.

Below is a roughly chronological though incomplete listing of semi-permanent resident artists:

| Name | Date of arrival to Istanbul | Details |

| Jean-Baptist

Vanmour (1671-1737) |

c.1699 | Flemish painter who accompanied the French ambassador to Constantinople and then worked mainly for French and other ambassadors in Turkey where he settled, lived for 37 years and eventually died. An example of his work. |

| Antoine Ignace Melling (1763-1831) | c.1782 | Worked as architect to the

Sultana Hatice in Constantinople, and remained for about 18 years.

Melling trained as an artist and architect, arrived

in Constantinople when he was only nineteen. A member of the Russian

ambassador’s household, he drew pictures for various dignitaries

and was soon introduced to Hatice Sultan, sister and confidente

of Selim III. Impressed by the splendid garden of Baron Hubsch,

minister of Saxony, the princess employed Melling to design something

similar for her palace at Ortakeï. Delighted with the result,

she then asked Melling to redecorate the interior of the palace

and, subsequently, commissioned him to design for her a completely

new palace in the neoclassical style at Defterdarburnu. In this

way, Melling became closely attached to the Ottoman court and

was probably more familiar with the Ottoman palace than any Western

artist since Gentile Bellini. Originally produced for the Sultan

and his sister, his drawings of the city and the Bosphorus, Buyukdere,

Bebek, the port, the arsenal are masterpieces of accurate observation.

They include what is probably the sole accurate representation

of the interior of an imperial harem. Melling returned to Paris

in about 1803 and in 1804 issued a prospectus for the Voyage.

Publication eventually began in 1809 and thirteen livraisons were

issued, the work being completed by 1819. The outstanding success

of the exhibition of the paintings on which the Voyage pittoresque

de Constantinople was based, earned Melling the title of

painter to the Empress Joséphine. |

| Thomas Allom (1804-72) | c.1838 from England | A travelling architect and draughtsman, some examples of his work. |

| Amadeo Preziosi (1816-1882) | 1842 from Malta | Buried in the Catholic cemetery of Yeşilköy (Aya Stefanos) / Istanbul. |

| Fausto Zonaro (1854-1891) | 1891 from Masi, Italy | The Sultan at the time bestowed upon him the title ‘Ressam-i hazret-i sehriyari’ |

| Leonardo De Mango (1843-1930) | ||

| Giovanni Brindesi | 1850s from Italy |

As can be seen there was a steady stream of Western artists who came to Istanbul and fewer to Izmir and elsewhere in Turkey for inspiration such as Sir David Wilke, however these transients cannot be considered to be Levantines. The only truly Levantine watercolour artist of note seems to be Sydney La Fontaine, of which only examples now 4 survive, through the vagaries of time.

As with other aspects, Istanbul is better covered in books on etchings and travellers descriptions catering for the European appetite for ‘Orientalism’, ref: ‘Gravür ve seyahatnamelerinde Istanbul (18. yüzyil sonu ve 19. yüzyıl) – Necla Arslan – Istanbul Büyükşehir belediyesi kültür işleri daire baskanlığı yayınları no:9 1992’ [Istanbul in etchings and travellers descriptions, end of 18th century and 19th]

A former director of Shell International Petroleum Company, Rodney Searight who worked in the Near East for many years, began collecting in the 1960s when there was little interest in oriental artists and his work led to the creation of the ‘Searight Collection’ in the Victoria & Albert Museum. This collection, 2000 watercolours and drawings, several thousand prints and several hundred illustrated travel books, is mostly of depictions of the lands of the Ottoman Empire and over 500 artists and travellers, mostly British are represented. A book is available to display some examples, (Voyages & Visions: Nineteenth-Century European Images of the Middle East from the Victoria and Albert Museum Esin Atl, Charles Newton, Sarah Searight, Victoria and Albert Museum - 1995) and there is an online archive magazine article ‘Vision of the Middle East’ viewable here.

However there is a minor fringe of ‘Levantine’ artists in this collection, which will be investigated and possibly reveal the nature of lesser known artists such as ‘Commander Carrelli’, M.C. Robinson, Raffael Corsini and Tristram Ellis.

Notes:

1- In Jan-Feb 2003 there was a major exhibition of Fausto Zonaro’s work in Istanbul and in conjunction with that a book has been published, ‘Ottoman court painter Fausto Zonaro – Osman Öndeş and Erol Makzume – YKY Istanbul and reviewed in the cultural magazine Cornucopia issue 28 - article in Turkish on the visit to Istanbul of the Prince of Wales Albert Edward VIIth accompanied by journalist Russell and artist Brierly:

2- For a more detailed look at the fine arts heritage of foreign visitors to Istanbul, web site, and a listing of W. H. Bartlett’s illustrations in the ‘beauties of the Bosphorus - Miss Pardoe’ as examples 1, 2 & 3.

3- There is an interesting ‘art and diplomacy at Constantinople’, article by Philip Mansel that demonstrates how the particular conditions enjoyed by the foreign ambassadors of the past ensured their residences became a depositary of fine art, ensuring the survival of many paintings to this day, and thus a visual window to the past.

4- Levantines also featured as sitters for various visiting portrait painters, in oriental garb, in the fashion of the time - examples:

5- If photography can be considered an art form, then here too we encounter the contribution of long-term Westerners and Levantines based in Turkey and Egypt. These include, for Constantinople: James Robertson, E. Coronza, Pascal Sebah (1823-1886), G. Berggren, Chusseau Flaviens, for Smyrna: Rubellin, A. Svoboda, Félix Bonfils, S.L. Cassar and others. Some of these old photos can be viewed here: and further information here:

6- For a brief listing of Levantines who having emigrated from Turkey, became successful in the singing and acting on stage as well as on film, click here:

7- The Levantine Theatre Group in Izmir gives yearly performances since 2009 under the direction of Ugo Braggiotti, and all performances in the 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014 seasons were sold out audiences and the cast and organisers would like to send a big thank you to all participants and supporters, click for flyers and information for 2011 - 2014 shows - video interview in Turkish - order the DVD on facebook:

8- Sylvia de Bondini was an amateur painter, born in a Levantine family in St Stefano, Constantinople, 1907 who married the Frenchman Jean Monnet, considered by many as a chief architect of European Unity - more:

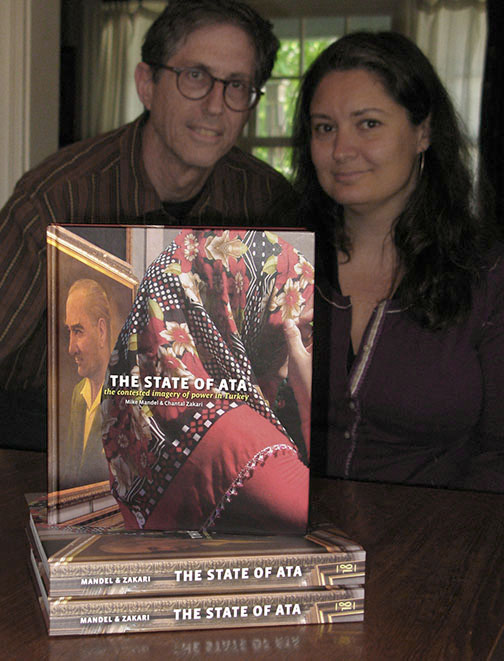

| The background to the book, ‘The State of Ata’ Interview conducted with Chantal Zakari and her husband and co-author Mike Mandel in August 2010 |

When did you first start writing? Is this your first book?

We started working on this project in 1997. The actual work on creating the book didn’t start until when we were at the MacDowell Art Colony (New Hampshire) in 2002. We knew we wanted to make a book even in 1997 but at the time we were more focused on gathering imagery and interviewing. We were in the research mode. We’ve always considered this as an artists’ book, a collection of our own imagery, found imagery, texts, interviews...

Mike has been self-publishing his artwork since 1971, in the form of ten different projects. Together we did The Turk and The Jew, first as a web narrative then as a book.

You spent 13 years researching the notion of the symbol of Atatürk with your husband? This is an impressive length of time for any study. Did the aims change through time, and how much did you change?

13 years seems long but not that long when you consider that we had to travel back and forth each year. There is an advantage in pursuing a project for a long time. Because 1997 was the year of the “soft coup” there was a heightened interest in using the imagery of Ataturk in opposition to the controversial religious government that was in place. We found ourselves in the middle of it. Thirteen years later we find that this is the perfect time for this book to be published.

Right from the beginning we were interested in looking at how Atatürk’s imagery was used in popular culture. We came to understand that this imagery was not only a popular response but a propagandistic tool to promote the interests of the secular media and the military. Soon we recognized that this symbol was in relation to other symbols that were also important, the headscarf for example, which is not only a religious but a political statement against restraint of freedom of speech.

Being from a Levantine family in Izmir, was your exposure to the imagery of Atatürk start at primary school? Do you think the imposition of this symbolism was to the same measure as say Jesus Christ?

Yes, my exposure began in primary school but even before that public sculptures and pictures were part of my daily life. Primary school was my connection to the wider culture and to the official story. The myth and the imagery is very similar to religious iconography.

Do you think your Levantine identity helps you to see outside the box, yet understand the complexity of the Turkish psyche?

Of course as a member of a minority group I am somewhat removed from the mainstream culture. I speak to this issue extensively in the book. We didn’t have a picture of Atatürk in our house. On the other hand, I received a secular education in the public school, and my teacher would give me a Christmas present each year. So even though I was part of a minority I didn’t feel completely left out. But really it is only when I moved to the US to study art that I realized that the imagery of Atatürk was so prevalent in Turkey. I was able to look at my own culture as an outsider.

Do you know when and where your various family branches came from and why to Turkey? Was a relative a ‘mentor’ to you in your early years? Is Izmir still ‘home’ for you?

Both sides of my family come from Italy but my dad’s side has lived in the Ottoman lands for eight generations. I don’t know the name, which region or reason why the first ancestors came. My great grandfather Jean Zacharie was a railroad engineer. His son, my paternal grandfather Charles Zakari was born in Edirne [archive views], Karaağaç (a satelite neighbourhood of this city) in 1900. Jean Zakari lost his job right before the Balkan War because he was involved in a workers uprising. Sometime around 1910 the family moved to Istanbul and then in 1912 to Izmir where he found a new job.

|

Railroad engineers (Edirne) Jean Zacharie (my great grandfather) is seated first one from the right

|

The Zacharie family, Dedeağac, Edirne August 15, 1906 (my grandfather is the little boy on the extreme left)

My grandfather briefly served in the Ottoman army in 1920 (as part of normal military service as an Ottoman citizen) but because army officials did not trust non-Muslims and they were soon let go. After the Revolution the family adopted the Turkish nationality. They changed the spelling of our last name from Zacharie to Zakari, a more phonetic version. He worked for the Ottoman Bank, a bank financed by Europeans, during the Revolutionary war (1919-23) and continued until his retirement in 1962. During World War 2 (1941-42) he was interned for 7 months along with other non-Muslims in Abant where İnönü’s government gathered non-Muslims for forced labour. They were forced to do hard labor breaking stones for the building of the Bolu-Abant road.

My maternal great grandfather, Fortunato Maresia, came from Italy and found a job working on the yacht of the Ottoman Bank in the late 19th century. My mom’s maternal grandfather Antoine Renault was a Frenchman who was married to a Greek woman. He owned a shop, Maison Renault, on Pera street (today’s İstiklal Caddesi) and was the tailor of the palace.

All four of my grandparents worked for the Ottoman Bank because they were fluent in French and that was the language of commerce during Ottoman times. Andre Maresia worked at Yeni Cami/Istanbul branch, his wife Francoise Maresia (Renault) Bankalar/Istanbul, Charles Zakari and his wife Evelyn Zakari (Gigho) both at Gümrük, Izmir.

|

My grandfather, Charles Zakari with a fez.

|

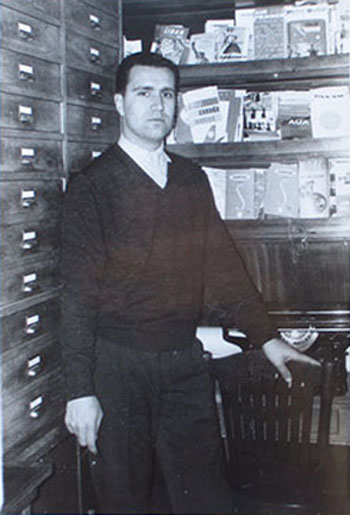

Jean Zakari (my dad) his first job at the Van Der Zee Shipping Co. [info on this family] Izmir circa 1962-1963.

My dad opened his own agency ICT Turizm in 1990. He was doing mostly incoming tourism. He put a lot of imagination into his work. Once he convinced carpet merchants to lend him carpets in order to cover a hill in Cappadocia so that the tourists would sit on them and watch a ballet performance against the volcanic rock formations. Another time he rented a ferry boat that carried cars across the Bosphorous. With the help of an interior architect and a gardener he transformed it into a floating harem. He is an inspiration to me. When he passed away in 1999 my mom continued the family business. Izmir is home for me.

Mike is from California. He had no previous exposure to Turkey and approached the project completely as an outsider. He studied photography and has been a practicing photographic artist since his days in college.

Is there a time an artist should back off subjects that can create too much friction or confusion in the community / society. Are you good at such compromises?

For us art can have conceptual power beyond the aesthetics. It’s not only a beautiful painting on the wall, art has power to enter into a dialogue that may include social issues, but for us it’s not a vehicle that is propagandistic or didactic. The space in between creates an opportunity for a lot of questions to open up, which can be provocative and disturbing but they don’t need to be answered by the artist. A work of art can create an opportunity for the audience to find their own answers.

In other interviews you have been quite critical of the Turkish press, accusing them of dumbing down the news, creating sensationalism and at times distorting the truth, and yet justifying this shortcoming by stating the ‘population wants this’. Do you think this is one of the tragedies of Turkey, a lack of good journalism leading to an ill informed public who are not given the tools to make good judgements of situations.

You don’t need to look far to find irresponsible and inadequate thoughtfulness in the way the mainstream media creates the news everywhere around the world. Turkish mainstream media is really no different than our experience of tabloid American journalism.

Is Turkey unique in interpreting in diverse ways the legacy of their national hero?

Turkey is not any different in creating a myth out of the legacy of the national hero. What may be unique in Turkey is that an entire narrative lays on the shoulders of one single person. For example, we were interested in photographing sculptures of Atatürk where he is portrayed as the great leader, teacher, warrior, father of a nation. In fact, even a political Islamists could find a picture of Atatürk to relate to. Toward the end of our project we would see in some cities new posters that showed Atatürk in the act of prayer.

During your long years of travel and research across Turkey what incident was the most bizarre?

We came with the intention to study and observe a powerful symbol in Turkish culture, and then inadvertently one morning in Ankara I became a symbol myself by holding up a picture of Atatürk. Certainly that was the most bizarre sequence of events.

Also bizarre and surprising to us was that we could find no trace of a real original image of Ataturk in any of the official government archives where we visited. Everything we found were third or fourth or tenth generation reproductions of images that I had seen since my childhood. The archives did not have a singular, authentic image of this man.

Not strange, but specific to Turkish culture, we learned how to navigate the nuances of Turkish public relations. While seeking access to the archives at TRT that we thought might yield something special we were directed to speak with “Ayşe hanım, the pregnant lady”. We soon discovered that Ayşe hanım had delivered her baby almost a year ago and that the archive was of little use, but what was curious to us was the convoluted path we had to take to get there.

More recently we made a portrait of a man in the streets of Afyon. He posed for us willingly, but a few minutes later we saw him running to catch up with us and asked us not to use his picture because it might be misinterpreted. His fear was that “this American” would take it out of context and who knows, in some newspaper he might be labeled as a terrorist. As this happened toward the end of the project it seemed a metaphor for a more contemporary anxiety about how people relate to foreigners.

Your art, and this book is clearly more art than history, seems to ask questions and yet offer no direct answers. Do you think it is a difficult notion for non-Turks to navigate this somewhat Eastern paradox, if I may put it that way?

We always considered that a significant part of our audience would reside outside of Turkey, primarily because the image of Atatürk is not that well recognized outside of Turkey. Especially after 9/11 the Western world is much more sensitized to the dynamic between the tradition of secularism and religion and how they collide and co-exist.

Any future projects planned?

Hard to tell at this point. This coming year we will be busy giving lectures about the book. We have lectures planned in the SW of the US, New York and Chicago. And a show in September 2011 in Boston.

Who are your favourite artists / authors?

This book is inspired by many artists’ projects and artists’ books we admire; Sophie Calle, Bill Burke, Susan Meiselas, Larry Sultan, Jim Goldberg.

If you could go back in time and space, which period and where would you like to live, at least temporarily?

It would be easy to connect with the nostalgia of earlier times when life was slower and less fragmented but at the same time people died younger and didn’t have as many experiences of the world. It’s always a give and take. But on the other hand as Ezra Pound once famously said, “the artist is the antennae of the race.” We may no longer need antennas but our role is to be responsive to the to social issues and mores of our time.

Do you think we are all tribal in nature, feel the need to belong to a series of interlocking communities, the overarching one being nationhood and to make us feel secure and advertise this ‘contentment’ we need to cling on to symbols to represent this belonging.

Chantal: We can talk about ourselves and our needs but the theory belongs to sociologists. I like coming back to Turkey, seeing my family, eating the food I grew up with, the smells, the chaos, the sun. I also belong to many communities in the U.S. my school, my neighborhood, my art community... Nationhood for me is different. I recently became a U.S. citizen and I will enjoy the right to vote. But I see nationalism as a forced identity. My family’s history and many other Levantine family’s history proves that belonging to a nation is a roll of dice.

Mike: Nothing would make me happier than to have a sense of national identity. But the United States seems to have lost its way. We have an historic moment with an African American president, he’s inherited wars that have left this country divided and alienated. The opposition party seems only interested in obstructing his programs no matter what they may be, so the end result is that any real sense of national purpose is lost within the inertia of a dysfunctional political system. People do believe in a variety of social, ethical, and economic values, and we do look for symbols as a shorthand to represent our thinking. Are you concerned about a “green” approach to how we plan for the impact of climate change? Then you have found a word, a symbol, to represent a very complex set of interconnected actions. As artists we create symbols within our imagery in order to affect our audience on a psychological or emotional level. Symbols are what we have to work with. If you’re asking, “Does Turkey need the symbol of Atatürk in order to maintain a sense of national unity and commitment to a secular future.” Well, let’s hope that Turkey’s future success as a nation will derive from more than just the memory of its first leader who has been out of the picture for the past seventy-two years.

Anything you would like to add?

Our distributor in the USA, D.A.P. is the largest art book distributor. Their European partner (which includes Turkey) is Thames & Hudson. When they saw our book they decided that it would be risky for them to distribute a book about Atatürk. Even though the book does not take an ideological position about Atatürk, Thames & Hudson, a European company, censored the distribution. Ironically, we have shown the book to journalists in Turkey and we’ve received 3 reviews in major national newspapers, Hürriyet, Vatan and Taraf. (For your Turkish readers I am including the links). All three reviews are positive which proves to us that Turkey is ready to embrace the discussion on this subject.

|

Click here for this book’s web site:

Click here for the recollections of Malcolm Hutton, who married into the Zakari family of Izmir