ALEXANDER VALLAURY’S ARCHITECTURE: AN OVERVIEW Seda KULA SAY Architect and PhD candidate, Istanbul Technical University |

|

Alexandre Vallaury (born Alexander Vallauri) is a prominent architect of the late Ottoman era; one who had remarkable impact on especially the formation of the late nineteenth century architectural atmosphere of Istanbul. His contribution to Ottoman architecture had been through about fifty major buildings he designed and realised, as well as the works of graduates of Imperial School of Fine Arts (“Sanayi-i Nefise-i Şahane Mektebi”) Department of Architecture, where he was the first and only professor of architecture during 25 years. He indeed led a very active professional career, that lasted roughly three decades between 1882-19111.

|

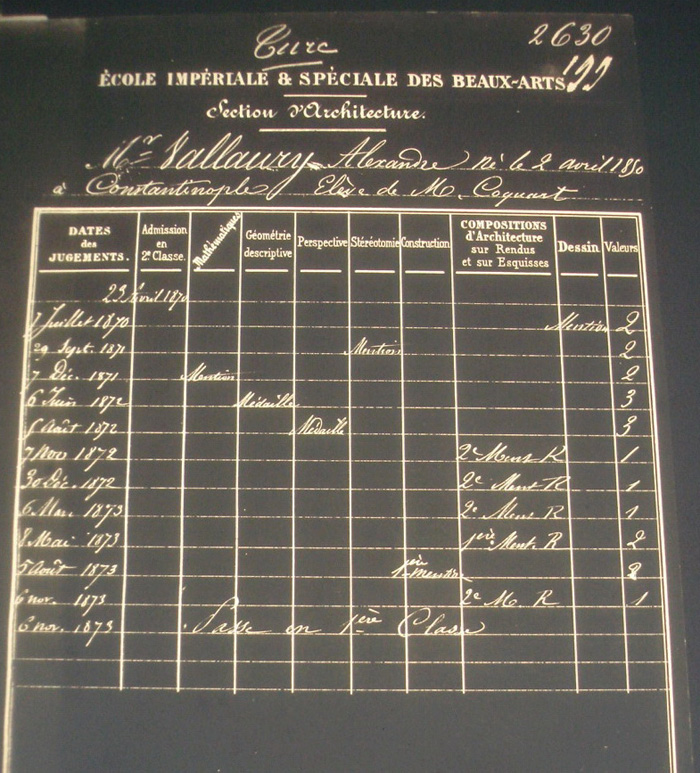

Vallaury received his architectural education in Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris between 1868-1879, then a worldwide renowned school in its field and hence lived about a decade in Paris which was then in the continuum of a very dynamic and comprehensive urban change. Vallaury’s strong affiliation with French world as opposed to his Italian-Greek origins probably started there. Along with a number of other Ottoman students in the same school, Vallaury was among the few - next to Pappa, Tahtadjian - who attended the school regularly to complete all courses and projects. And following, he had the opportunity to become the author of a considerable number of edifices. As such, Vallaury can be counted as the foremost representative of Beaux Arts architecture in Ottoman Empire.

|

At the time, classical Beaux Arts architectural principles based on a close as possible pursuing of Roman or Renaissance architecture, were already abandoned to address changing political, professional and technological conditions, especially under the impact of the discourses of architect-theoricians like Labrouste, le-Duc and Garnier. Hence it was the era of eclecticism in architecture which incorporated a compromise of political expectations, historical references as well as new building materials and technologies, a trend enforced by modernity and one which was reflected in Vallaury’s works throughout his career. Vallaury was enrolled in Coquart’s atelier at school, a professor known to have restored the school’s historic building and also carried out some archaeological research in Aegean islands.

Vallaury, so far as can be traced, made his first appearance in Istanbul in 1880 as a yet unknown architect in the ABC Club exhibition. One of his first known professional works in 1880s, was the Mansion for the ex-khidive of Egypt, a very important political figure of his time, which proves that Vallaury showed considerable success in penetrating the network of élites in Istanbul.

|

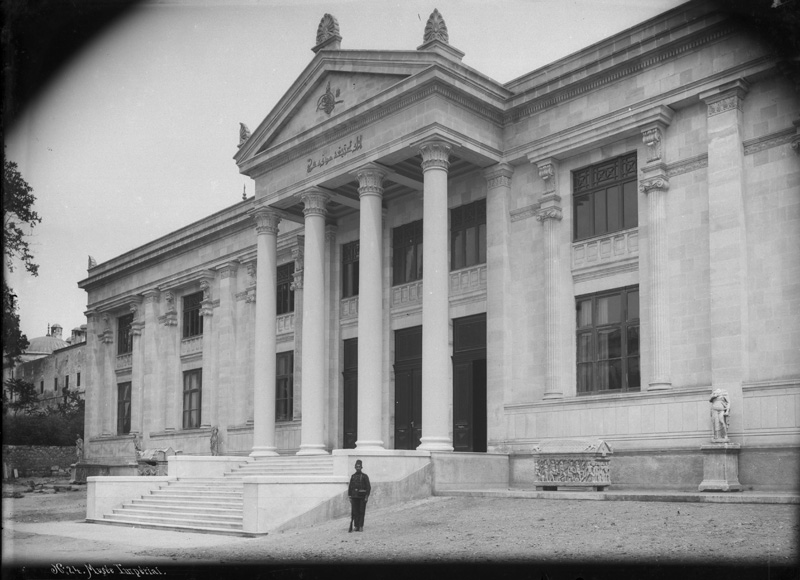

He indeed was also in the team of Osman Hamdi Bey2, who was then assigned the director of the Imperial Museum (“Müze-i Hümayun”) and one of Vallaury’s first occupations under his patronage had been the formation of a cultural site, a pseudo-Beaux Arts campus at the foot of the Old Palace, which in addition to the 15th century Çinili Kiosk would comprise a new building to serve as a museum and a school building for the newly established Imperial School of Fine Arts where he was also assigned as the professor of architecture. School building would be ready by 1883, whereas the plans he prepared for the museum would be implemented only in 1891, due to state’s financial problems.

|

This first decade of Vallaury’s career must have been one when he had strong connections with the Levantine community and the Societa Operaia in Istanbul, as well as Osman Hamdi Bey and relevant circles, not to forget his Italian and Greek origins, the successful ongoing pastry business of his family in Istanbul nor his brother settled in Egypt. It was due time to prove himself as a capable architect. His relation with the freemasons lodge Risorta Italia must also have started then. His contribution to the planning of the new locale for Societa Operaia also falls into this period. His project in 1884 for the building to house the Cercle d’Orient Club and the residence of Abraham Paşa, the ex-secretary of the Egyptian khidives and a important banker of his time, was a true success; it was a show-offy Parisian apartment in the heart of Pera.

|

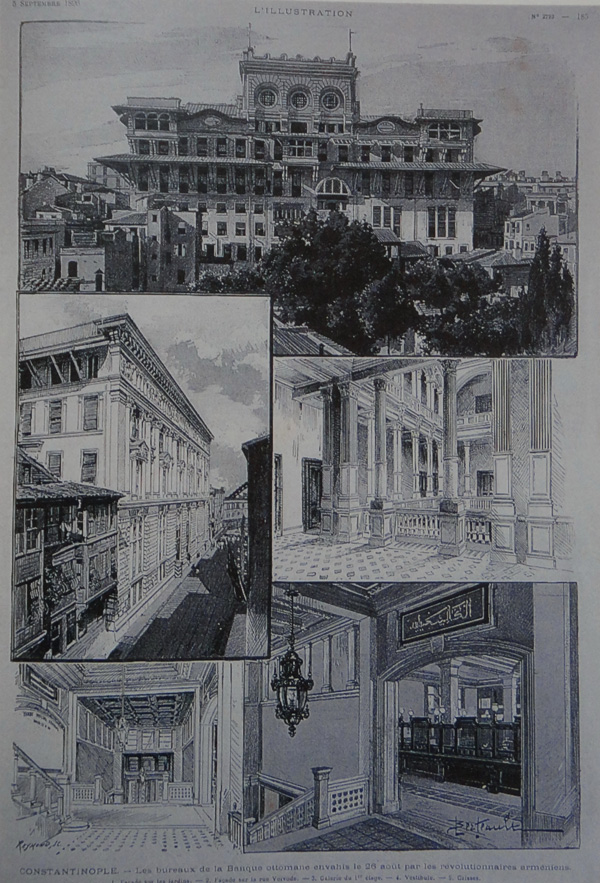

Vallaury’s alleged authorship of the Cibali Tobacco Factory in 1884 could also imply early relations with the Tobacco Régie. However he is sure to have gained confidence of the palace and bureaucracy, as he also built the mansion in Çengelköy for Prince Vahdeddin and the seaside Mansion for Serasker Rıza Pacha in 1880s. As for the Eminönü branch for the Ottoman Bank that he built in 1887, this was his first known work for the sector of finance.

|

Finally the small, but curiously orientalist Hidayet Mosque that he rebuilt in Eminönü for the use of Customs Offices is noteworthy in that it was his first known contact with state’s Customs Administration (“Rüsumat Emaneti”), where he would shortly be recruited as the chief architect in 1889. This decade ends with Vallaury building the Turkish pavillion in 1889 Paris exhibition, an international experience patronaged by the Tobacco régie, and a chance for Vallaury to revisit Paris and no wonder see the much discussed Eiffel Tower along with many other architectural innovations.

|

Though it was a challenge for an unknown architect to prove his capacities in a capital city with considerable architectural heritage, Vallaury’s case may not have been very difficult at least in the beginning, for it was a rather stable period under Abdulhamid II’s reign when financial and political crisis were overcome with new investments on the way, though at the cost of freedom, and when local capable architects were scarce. In parallel, Istanbul had to take over the interrupted modernisation project of Tanzimat to at least keep up with the exigences that international trade imposed and to have a word in the rivalry of especially other port cities. The suppliers and contractors were mostly British and often French which made it all the more convenient for the levantine population of the empire, which had been the interface of the Ottoman world with Europe all along. There was soaring demand for know-how and workmanship to build according to new technologies and building programmes. Hence, it could be claimed that Vallaury returned to his hometown Istanbul at a rather advantageous time. Statistically speaking, Vallaury seems to have worked in 1880s mostly for the government, that is the palace, state and bureaucracy. The patronage of Muslim or levantine private commissions accounts to only half of this state work. As for the geographical distribution of his works, those in the historical center of Istanbul double those in Galata, Pera and Istanbul’s periphery.

In these early commissions of his career, Vallaury can be sensed to have closely followed the patron’s preferences; for he incorporated completely different stylistic attitudes for buildings realised in a short span of time; such as the purely neoclassic museum building, the Khediv mansion full of Egyptian references, the strictly orientalist Hidayet Mosque and the Haussmanian apartment house-like Cercle d’Orient building.

The second decade of Vallaury’s career saw the share of private commissions outnumbering those of the state considerably, so that they were nearly four times as much. In parallel, Vallaury’s works in Galata and Pera region would triple, whereas those in historic center would decrease by one third. Soaring demand for projects for the finance, tourism and entertainment sectors settling in Galata-Pera region and the development of Istanbul suburbs to accomodate touristic and entertainment services accounted for this change. The famous Ottoman Bank headquarters, Tepebaşı Pera Palas and Tarabya Summer Palace hotels, Banque de Change, Union Française building, Headquarters of Public Debt Administration (“Düyun-u Umumiye Idaresi”), Tokatlıyan Hotel in Pera, Prinkipo Palas hotel in Büyükada later converted to a Greek orphanage, were all products of 1890s. Vallaury also received private commissions like Dégucis house, a primary school building for the Italian community - in cooperation with Raimundo d’Aronco -, and a late realisation of Imperial museum plus its annexes.

|

|

|

|

|

The change in patronage of commissions was probably due to the destructive earthquake of 1894, after which the Ottoman state had to use much of its already limited funds to recover, restore and save, rather than embark in new investments at least for some time. So the pressing demands of a port city in need of modernization were covered by concessions given to foreign capital holders, which resulted in an influx of foreign companies and their concessioners in Istanbul. Following, Galata-Pera region’s dominancy over the historic peninsula was sealed by the swift development of a financial center there, by the end of the decade.

But at the same time, Vallaury’s services for the Ottoman state became even more, next to his commissions patronaged by the new private capitalholders, since he was assigned the architect-in-chief position of the Customs Administration, and became one of the major advisor-implementor architects in the post-earthquake city restoration council, next to his continuing professorship at Imperial School of Fine Arts, from where there must have been already a number of graduates who joined the architectural task force in the capital city or cooperated Vallaury in some of his projects, as the evidence suggests. These important responsibilities in key state institutions, must also have let Vallaury have considerable word in the construction and infrastructural activities and tenders getting more and more comprehensive and especially related to considerable transformations in the Ottoman capital city. Vallaury had considerable respectability and fame by then.

However it would be a mistake to consider him all alone in decision-taking processes of these rather huge projects; during 1890s, he was most of the time cooperating with other architects and increasingly engineers. Among these, German architect Jasmund and later Jasmund’s student Kemaleddin Bey must have been among those who were most critical of Vallaury’s architecture. As for Raimundo d’Aronco’s intervention, he seems to have been both a serious rival but also a partner for Vallaury. This was apparent in many projects such as the restoration project for Grand Bazaar, the primary school for Italian community or the restoration of customs house buildings and depots, where these two colleagues cooperated.

Vallaury’s cooperation with d’Aronco extends well into the next decade or the twentieth century. Their most important common product is no wonder the Imperial School of Medicine at Haydarpaşa dated 1903. Apart from this, Vallaury is known to have been very much engaged in several Customs House buildings, namely the İzmir customs house annex, Thessaloniki customs house and Istanbul Eminönü Customs House. His other works in 1900s are, mansions for Yanyalı Mustafa Paşa, Rıdvan Pasa, Müşir Zeki Paşa, his own houses in Tepebasşı and Büyükada, a monument for the birthday of Abdulhamid II on the jetty in front of Haydarpasa, Ömer Abed Han office block in Galata, a police station in Pangaltı, Ottoman Bank Lodging Apartments in Taksim. He is also attributed to authorship of a hospital building in Samsun, some annexes of Yildiz Palace in İstanbul, some railway stations and hotels in Anatolia for Anatolian Railways Company, some other private residences such as Cemal Reşit Rey house, Visnecizade mansion as well as Bazer Yezid Mosque.

|

|

During the early years of the twentieth century in Ottoman Empire, the German presence and influence were increasingly felt due to changing government policies. Railway and railroad facilities construction was the most important investment and was completely trusted to Germans at the time. Concurrently, the most serious opposition group named Ittihat ve Terakki mostly organized in the provinces, was swiftly evolving to a party.

Vallaury was a very experienced and reputable architect by then. He was known to be close to francophone countries and actually he already had changed his nationality to French. But he was also observed to be working with Germans for Anatolian Railway projects. It should be noted that competition among architects, engineers and contractors especially for government tenders had become really fierce by then. The general emphasis seems to be on solidity and reliability of the structure;and cost reduction was essential to win in tenders. Meanwhile, the introduction of new building technologies, especially the reinforced concrete, in spite of prejudices, proved to be really fast, since it lowered the costs considerably.

Vallaury’s choice among new building technologies seemed to favor iron, steel and glass, as can be observed from his projects for the reconstruction of Grand Bazaar, customs house buildings and Medical School, whereas he might have confronted reinforced concrete with some reservation. Though the reinforced concrete material and know-how supplier of the time was French Hennebique, Vallaury is not known to have cooperated with them except in Thessaloniki customs house and only via the engineer implementing his plans. However reinforced concrete in a few years became the technology of choice among Ottoman architects and engineers, including some of Vallaury’s old students. The new construction technologies adopted, no wonder fostered engineers’ position to the disadvantage of architects. What is more, state funds and enthusiasm of foreign capital to invest in Ottoman Empire seemed to lessen, due to global and local economic and political factors, hence a gradual contraction in construction industry was unavoidable.

Hence with Vallaury’s architecture in the first decade of 20th century, we see the impacts of changing conditions. First this is the period when he produced most of his works outside Istanbul. Secondly he had been very much involved in discussions related solidity of his buildings. However he did not seem to be predominantly motivated by pan-islamist nor nationalistic trends.

1909 revolution was a breakpoint. All the investments were stopped; there no more was influx of foreign capital; many distinguished Levantine people were leaving the country. Vallaury’s old friends Bello and Osman Hamdi Bey died one after the other. Vallaury must not have been on especially bad terms with the then governing Ittihat and Terakki Party, since he was assigned the task to restore the Parliament building. However we see that he also resigned from all his responsibilities and left Istanbul for Grasse, France, shortly after the inauguration of one of his final works the Eminönü customs house in October 1909. Vallauri is not known to have continued his architectural career in France, though he was still in charge of his unfinished works until about 1911.

Throughout his career, Vallaury has been a loyal implementer of Beaux Arts composition principles. He must have been relied upon also to convey this knowledge and theory to new architects, through his professorship at Imperial School of Fine Arts as well. Generally speaking, his stylistic concerns are a reflection of the eclecticism that reigned in France then, for in most of his works is sensed an effort to reach a balanced composition through a compromise of a wide range of historical and geographical references, an architectural conduct that resulted in producing a architectural repertoire of his own, incorporating both neoclassical elements and borrowings from Ottoman architecture in stylised form.

SELECTED BIBLIOGRAPHY ON ALEXANDRE VALLAURY

BATUR, Afife, 1993. “Ondokuzuncu Yüzyıl Sonu İstanbul Mimarlığında bir Stilistik Karşılaştırma Denemesi: A. Vallaury - R. D’Aronco / A Stylistic Comparison in Late Nineteenth Century Istanbul Architecture: A. Vallaury - R. D’Aronco”, in Osman Hamdi bey ve dönemi, Sempozyum 17-18 Aralık 1992, Arkeoloji Müzeleri Kütüphanesi – Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, İstanbul.

CAN, Cengiz, 1993. “İstanbul’da 19. Yüzyıl Batılı ve Levanten Mimarların Yapıları ve Koruma Sorunları / Western and Levantine architects in 19th century Istanbul and problems in the conservation of their buildings”. PhD Thesis, İstanbul: Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü.

CEYLAN, Oğuz, 1995. “Alexandre Vallaury ve İki Yapısı / Alexandre Vallaury and His Two Buildings”, Yeni Tıp Tarihi Araştırmaları; Vol.1 pp. 172-81.

ÇEVİK, Umut, 2001. “Alexandre Vallauri ve Yapıları Üzerine Bir Araştırma / A Research dedicated to Alexandre Vallauri and his construction projects”. Master’s Thesis, İstanbul: Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü.

DOGAN KILIÇ Alkım, 2006. “Vallauri Cephelerinde Klasisizm / Classicist facades of Vallauri”. Master’s Thesis, İstanbul: İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü.

KAYAALP, Nilay, 2008. “Pera’nın yersiz yurtsuz kahramanları: Vallauri ailesi, Edouard Lebon, Alexandre Vallauri ve M. Vedad Tek / Deterritorialized actors of Pera: The Vallauri family, Edouard Lebon, Alexandre Vallauri and M. Vedad Tek”, Master’s Thesis, İstanbul: Yıldız Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü.

KULA SAY, Seda, 2013. “Alexandre Vallauri And His Architectural Works For The Italian Communıty”, in “Italian architects and builders in the Ottoman Empire and modern Turkey, 1780-2000”, international conference 8-9 March, İstanbul.

KULA SAY, Seda, 2011. “A Post-1908 Project of Vallaury: Customs House in Thessaloniki”, in “14. International Congress of Turkish Arts”, international conference 12-15 September, Paris.

NASIR, Ayşe, 1991. “Türk Mimarlığı’nda Yabancı Mimarlar / Foreign architects within the context of Turkish architecture”. PhD Thesis, İstanbul: İstanbul Teknik Üniversitesi, Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü.

SÖNMEZ, Zeki, 1983. “XIX. Yüzyıl Sonlarında Türkiye’de Mimar Sorunu ve Sanayî-i Nefîse Mektebi’nin İlk Mimarlık Hocası Alexandre Vallaury / Questioning Architects Towards the end of XIXth Century Turkey and the First Professor of Architecture at the Imperial School of Fine Arts Alexandre Vallaury” in IV. İstanbul Sanat Bayramı Sempozyumu, İstanbul, s. 30-48.

ÖZKURT, M. Çağlayan, 2005. “Düyun-u Umumiye İstanbul merkez binasının Tanzimat sonrası Osmanlı mimarlığı bağlamında değerlendirilmesi / Evaluating the İstanbul central building of Public Debts administration with respect to Ottoman architecture after Tanzimat period”. Master’s Thesis, İstanbul: Hacettepe Üniversitesi, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü.