This study article will explore the radical changes in Izmirs transportation infrastructure during the 19th century, the culmination of its rising prominence as one of the main Eastern Mediterranean ports that started during the latter part of the 18th century. One of the chief results of this development were the railways which had the double result of creating new living areas near the cities to which the line went but also providing a means of transporting goods from the wide Anatolian hinterland to Izmir and thence to the European ports as export. The article will focus on the Walker family whose head was employed by the Ottoman Railway Company (Smyrna - Aidin) and lived on this line the sub-station village of Aziziye (modern Çamlık) as revealed and traced with their archive photos.1

Public Transport in Smyrna pre-19th century

The first public transport in Smyrna was by sea, across the bay. The kayıks of Smyrna had their own evolution across centuries, providing a small scale service2 to points across the bay, chiefly between Konak and Bornova (Bayraklı) piers. For land public transport, till the middle of the 19th century, the extent was horse-drawn carts within the city.3 During this time before any major city infrastructure investment, the descriptions of travellers of the time paint a picture of problems encountered within the city arteries: The loads on the camels are as wide as to scrape the shop facades, and if encountered you are forced to dive into the nearest shop...4

Camel caravans were the means of long-range transport. This method of transport and goods conveyance was a centuries old tradition in Anatolia. Following the lay of the land and passes, the routes followed were generally from the dawn of time, criss-crossing Anatolia.5 The new railway lines, laid out from the middle of the 19th century onwards, followed closely many of these old trails.

By the start of the 19th century we see a reduction in the number of long-range camel caravans.6 Their role was reduced from general transport to conveying the areas agricultural produce to port. Security on the road was now provided by a form of protectors of caravans, and no longer the old over-lords. With this system the caravan owners were not only providing the service of changing the location of goods but also effectively a credit provider and marketeer.7 The camel driver would convey the goods to Smyrna, sell the goods at a price he would set and receive the sale commission. (This led to a strong cameleers culture that is still maintained today with festivals of camel wrestling in areas populated by the nomadic Türkmen-Yörük tribes.8) All these factors contributed to making camel transport quite an expensive option. Camel caravans were slow, costly and suffering from a recurrent threat of attack in the hinterlands of Anatolia.9

A single camel could carry between 250-450 kg and cover around 30 km. a day. At the time of the laying of the railways there were around 100,000 camels in the Aydın area working on this transport, so it is not hard to imagine how dramatic the effects of the arrival of the railways on families who were engaged in this trade.10

Smyrna-Aydın Railway

This railway project was the second in the Ottoman lands and the first in Anatolia, providing an alternative to a system of land transport with deep roots and fixed for centuries. Britain that had considerable trade activity across the Levant region was able remove a lot of trade restrictions with the Balta Limanı agreement signed in 1838, began to promote modern transport within the Ottoman Empire. Before this agreement it was forbidden for foreigners to engage in direct internal trade, forcing the British merchants to rely on local Greek and Armenian agents, with the advantage of their language, custom and trade knowledge, both in collecting the agricultural goods or selling these on to the Aegean market. Post 1838 British investment was free to enter the market without the need for these intermediaries.11

The British investors who backed the railway investment were guided by the 1,086 British merchants operating in Smyrna as well as the other Levantine and non-Moslem traders. The joint British approaches led to the approval of central government in Constantinople in 1856, laying the foundation for this concession. The concession holders were Robert Wilkin, a second generation venture merchant in Smyrna and partners: Joseph Paxton, George Whytes, Augustus William and William Jackson.12 Despite the company having internal problems, in 1866 the line reached Aydın. The project widened with side branches and thus truly reached the hinterlands. A good example of this spread was the 1879 additional line between Torbalı and Tire. In earlier times (14-17th centuries) Tire was a major conduit for the agricultural produce of the fertile lesser Meander valley. In addition the railway reaching Ödemiş extended this inter-connectivity further.

The railways also hastened the creation of the environment for foreign investment to flow in the hinterlands of Smyrna and Aydın. With the completion of the building of the railway British venture capitalists began to buy large tracks of land in the area. This played an important role in the transformation of the regional agriculture to one based on capitalist principles. In addition, with the laying of the railway tracks, came also the construction of abodes for Levantines to live along the track, bringing this community and culture from the coast to the hinterlands. An example of this are the houses built for the railway engineers at Çamlık village, Selçuk prefecture within Smyrna province; a community fully retaining their Western culture and life-style.

A Levantine residential zone at Aziziye / Çamlık.

The second half of the 19th century witnessed changes brought about by the introduction of the railway into the landscape, including the creation of new housing zones. With connections established with areas far away from major cities, new urban elements were quickly introduced. One of the people instrumental in these changes was the engineer Joseph Walker. He was born on 12 March 1840 in Calke, Derbyshire, as the elder brother of a two sons family. His father worked during the 1830s/40s at Colehill Station on the Birmingham / Derby line as the tracks inspector. By the 1860s Joseph and his brother William had migrated to the Ottoman lands, living in Smyrna. They came as part of the work-force of the Smyrna - Aidin Railway Company that had won the imperial concession. The family home was near the main Punta station of the company, the address at the time being 1st kordon no: 642, today Atatürk Boulevard 448.

Joseph marries a lady by the name of Regina and on 12th June 1870 their son Charles is born who grows up also to become an engineer. When the son marries the family grows further, and the Walkers spend most of the year in their Punta house, spending the summers in their summer-house at Çamlık. With the construction of the Punta Railway Station, the area is parcelled on speculative lines for new housing. The terrace housing style built here is admired by the locals and imitated in many other old and new districts. This style of terrace housing dominates the area around Punta Station that was at the time known as the English neighbourhood. The Walker house here also was built to this style. It is two storied, asymmetric frontage and with a wooden cumba [enclosed balcony]. As typical to Smyrna residences of the time, it is laid out on a short to long axes.13

From the first half of the 19th century, pictorial depictions in the Ottoman Empire that were typically engravings were transformed with the introduction of photography. In particular Western expatriates living in the Ottoman geography began to take copious photographs as keep-sakes from their travels. Many local Western commercial photographers came to the fore in this era, foremost among them being Rubellin. The Walker photographs taken at their holiday residence of Çamlık are of a keep-sake nature, forming the central evidence of our research.

One of the things to note in these photos is the garden and landscaping being done according to Western cultural lines. The pastoral scene is a synthesis of Aegean scenery with vines beyond within ideal horse-riding country.

During the construction of the Smyrna - Aidin Railway the engineers had to tackle some tunnels locally. The 230 m. tunnel before Çamlık did not offer much in the way of difficulty, however the tunnel after this village at 1014 m. was excavated with many difficulties taking a long time to complete. This tunnel was a frightening prospect for passengers of the time. The accounts of the time, mentioned in Nedim Atillas book, describe the passage through the tunnel thus: After the darkness and lack of air within that tunnel, the pleasurable contrast of experiencing the refreshing air of the Aziziye woods is one to behold.14 This pleasant atmosphere is proved by the picnic family group scene in one of the photos, with dense vegetation visible in the background.

The Walker family house in Çamlık was two storied and made of rough stone. One of the features of this house is the veranda supported by 4 uprights, acting also as the entrance facade. The front door carries the elements of typical Smyrna houses of the time. These doors of brass door-knob and cast iron facade were very popular. The wooden threshold of the door was reached by two marble covered steps. This door was topped with an eaves supported by a wooden cage from below and topped with a tongue design for decoration. This portico was in turn topped with a terra-cota tiled roof.

The photos reflect the growing size of the Walker family. The happy family group compositions within gardens also point to the spread of the earlier established Levantine life-style in the busy port of Izmir, now in evidence in points of Anatolian hinterland. The Walker family were English in origin, but by migrating to Smyrna and Anatolia with the railway construction, they acted as somewhat pioneers in both their family destiny and the community they came into. The family were able to observe first-hand the brand new innovation of railways introduced across huge areas of the Ottoman country.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sources:

Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnamesi [Evliya Çelebi Travel Journal], IX. Kitap, YKY, 2005

İhsan Yahut, Egenin Deve Güreşi Şenlikleri [Camel Wrestling Festivals of the Aegean], İzmir Kent Kitaplığı Yayınları, 2009

İlhan Tekeli, Ege Bölgesinde Yerleşme Sisteminin 19. Yüzyıldaki Dönüşü [The transformation of urban development of the 19th century Aegean region], üç İzmir, YKY

Nedim Atilla, İzmir Demiryolları [Izmir Railways], İzmir Kent Kitaplığı, 2001

Orhan Durmuş, Emperyalizmin Türkiyeye Girişi [The Entry of Imperialism to Turkey], Savaş Yayınları, Ankara 1982

Rauf Beyru, 19. Yüzyılda İzmir Kenti [Izmir City in the 19th Century], Literatür Yayıncılık, Mart 2011

Rauf Beyru, 19. Yüzyılın İlk Yarısında İzmirde Kent içi ve Kent Çevresi Ulaşımı ve Trafik Düzeni [The organisation of transport and traffic in the first half of the 19th century with and surrounding Izmir] Son Yüzyıllarda İzmir ve Batı Anadolu Uluslararası Sempozyumu Tebliği, 1994

Şeniz Çıkış, Modern Konut Olarak XIX. Yüzyıl İzmir Konutu: Biçimsel ve Kavramsal Ortaklıklar [The 19th Century Izmir House as a Modern Abode: Similarities in Style and Meaning], Metu. Jfu, 2009

Vedat Çalışkan, Kültürel Bir Mirasın Coğrafyası: Türkiyede Deve Güreşleri [The Geography of a Cultural Inheritance: Camel Wrestling in Turkey], Selçuk Kent Belleği Yayınları, 2010

Short article written by family descendant Sally Elliott, History of the Walker Family in Western Turkey, 2001

1 The photographs displayed here and maps referred to in this study belong to the Selçuk city archive centre, and I thank them for the access provided for me.

2 Rauf Beyru, 2011: 263

3 Rauf Beyru, 1994: 9

4 Rauf Beyru, 1994: 9

5 The most famous ancient trail across Anatolia is the Royal Road. Right from ancient empires the leaders knew that the key to holding firm on to these territories lay through controlling the strategic roads. The big powers of the past applied this principle and the remains of the Roman or Hittite roads are still visible today.

6 İlhan Tekeli, 1992: 131

7 İlhan Tekeli, 1992: 131

8 İhsan Yahut, Egenin Deve Güreşi Şenlikleri, Vedat Çalışkan, Kültürel Bir Mirasın Coğrafyası: Türkiyede Deve Güreşleri

9 For the description of an attack on a caravan, consult Evliya Çelebi Seyahatnamesi, IX. Kitap, p: 151

10 O. Kurmuş, 1982: 62-64

11 İ. Tekeli, 1992: 79

12 N. Atilla, 2002: 56

13 Şeniz Çıkış, 2009: 213

14 N. Atilla, 2002: 70

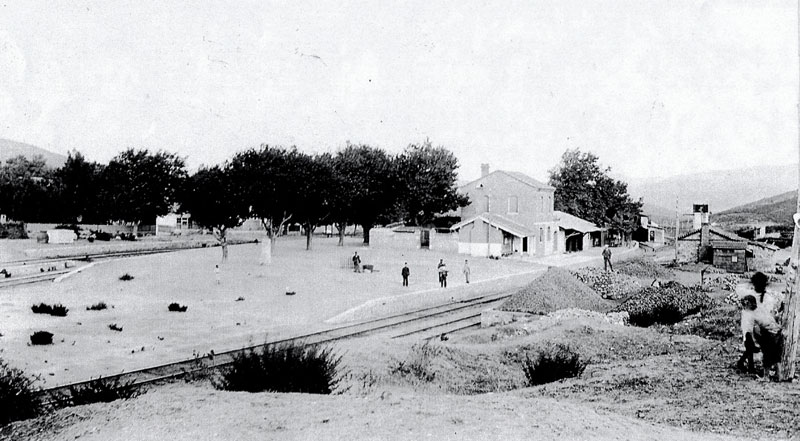

Photo of the Purser family farm in Aziziye / Çamlık:

Photos of the other Walker family house in Punta / Alsancak and the present state of the Walker house in Çamlık:

Thesis on the Development of Railways in the Ottoman Empire and Turkey, Sena Bayraktaroğlu, 1995, and a dissertation by Francisco Javier Valenzuela The Construction of the Smyrna-Aidin Railway in Southwestern Anatolia, 1856-1866; a discussion, 1975.

Ali Özkans other research article: Hotel Huck Smyrna: Outstanding Hotel of the Glorious Port-City.