Hotel Huck Smyrna: Outstanding Hotel of the Glorious Port-City written by Ali Özkan and translated from the Turkish by Görkem Daskan, 2012 |

|

Izmir is a city that has been a home to a number of communities throughout its history till the present. Having started its existence as a trade city colonised by the migrants from Central Greece in the 10th century BC, Izmir, especially during the 19th century, as an entrepot centre, became the hub of people from many different religious and national backgrounds settled there for commercial reasons. Smyrna1, in the same century, saw a tremendous urban progress that claimed that transformed the city effectively to the metropolitan of Minor Asia. The contemporary westernisation movement initialised by Ottoman bureaucrats and intellectuals in the empire not only had reflections in military, administrative and economic grounds but also led to the rebirth of Ottoman cities designed in line with the concepts and lifestyles attributed to the West.

The Frank Street sets for itself a special place in the writings of the Western travellers who visited Izmir during and before the 19th century. This street and the quarters placed in parallel to that were the environment where one could experience the most westernised way of living in Smyrna. With the completion of the constructions of the Cordon (the quay) and the docks with the financial help provided by Ottoman officials, the area became the stage for and the pioneer of the Ottoman modernisation of Izmir as a whole. The four kilometres long permanent quay with its promenade was indeed a centre of attraction for residents and visitors. For all these reasons, the periphery of the quay gradually became the most popular part of the city.2 The new high-value plots were filled with the office buildings of banks, ship agencies, commercial enterprises, insurance agencies, consulates and hotels created according to the western style of city planning and thus the city was given a new profile and silhouette.

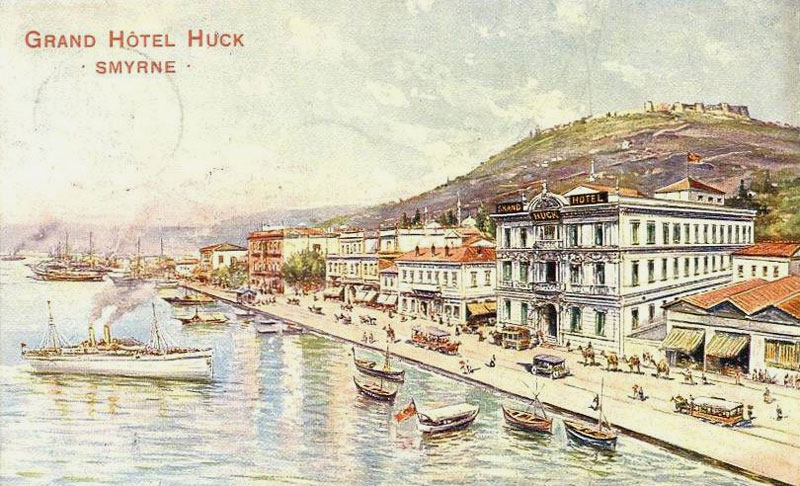

This article aims to examine the Grand Hotel Huck, one of the edifices that have occupied an important place in the urban history of Izmir-Smyrna. During the catastrophic fire of 1922, like many other monumental buildings of Izmir, Hotel Huck also perished. The hotel, having being documented many times in the early period of photography and postcards, used to be a popularly frequented place by Smyrniotes throughout the era.

The concept of hotel accommodation, with its entry into the Ottoman world in tandem with the westernisation movement, became a milestone in the Ottoman view of accommodation and architecture. These institutions being imported from the West were put into practice firstly in the cosmopolitan port cities of the empire like Istanbul, Izmir, Salonika and Beirut.

Izmir, with its dense trader Levantine population, cosmopolitan urban fabric and its long-time close ties with European countries as a result of its port-city qualities a window to the West, was a special case in the context of the adaptation to and development of the hotel sector in the Ottoman territory.3

The emergence of modern hotels started a whole new era in the long history of lodgings which still exists today. In the same century, centuries-old lodgings like the caravanserais and inns which had deep roots in the Turkish culture slowly left their places to modern hotels. With the opening of the Izmir-Aydın railway line and the securing of a faster and a more efficient mode of transportation to the hinterland of Izmir, caravans and caravanserais began to lose their rationale and gradually disappeared.4 The inns found in city centres, on the other hand, managed to survive serving as depots and offices/stores.

19th century hotels, beyond enjoying a new type of architecture that offered different opportunities than inns did, maintained higher standards and paved the way for modern hotels.5 The massive, complex hotels installed in proximity to the quay were of a level of quality to compete with their contemporary equivalents available in Europe.

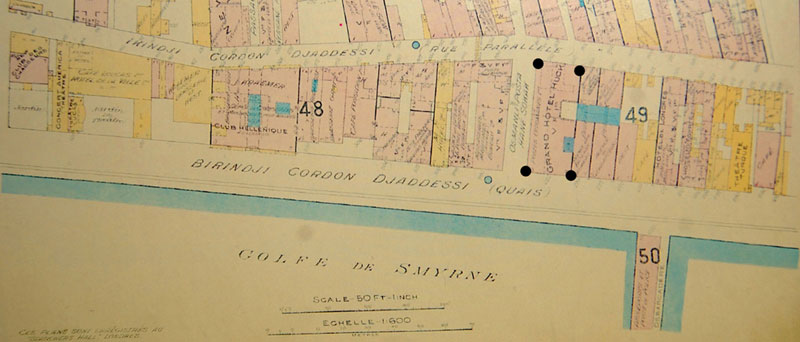

Truly one of the grandest buildings in Izmir, the Grand Hotel Huck was located at the intersection of the 1st Cordon Street and the Ottoman Post Office Street.6 On the ground floor of the building, on the left, was situated the Ottoman post office.7 Being a 19th century building, it used to occupy the parcel number 49 according to the insurance plan of 1905. This plan, made by the English civil engineer Charles E. Goad, especially has laid out the details of districts such as Kemeraltı8 and the Frank Street.9

The hotel was named Hotel M. Mille, Hotel des Deux Auguste and finally the Grand Hotel Huck in chronological order.10 In a photograph by one of the early photographers of Izmir, Rubellin, dating 1880, it could be seen in addition to the sign placed high on the parapet that read Hotel des Deux Auguste and the signs on both sides of the main door and just above the first-storey balcony door that read Hotel M. Mille. In 1888, the hotel was run by a Berliner called Madam Huck and later to be named after her.11

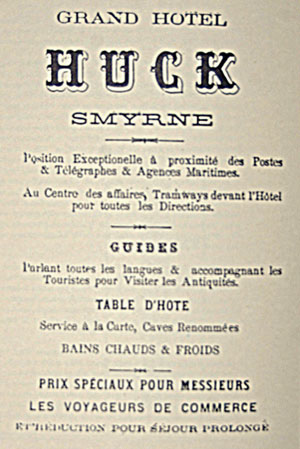

The restaurant based on the first floor of the hotel was known to be quite a popular and an attractive spot at the time.12 An advertisement published in a city guide in 1894 shows that the guests of the Grand Hotel Huck were presented with a fixed menu, famous alcoholic drinks, cold and hot baths and tourist guides fluent in every language.13

The above-mentioned insurance plan of 1905 bears a special importance in terms of pointing out the architectural details of the hotel. Though the hotel was laid out differently in the plan in terms of the plot order, it was in reality based on a scheme of planning that involved a middle passageway. Being located on the edge has allowed the particular plot the advantage to having three facades. However, as stated above, the ground floor of the building that faced the Ottoman Post Office Street was occupied by the Ottoman post office. By this way, the entrance hall of the hotel had to be located in the passage crossing the hotel building from end to end and connecting to the streets of the 1st and 2nd Cordon. There was a restaurant situated on the right side of this passage.14 In the proximity, there were the buildings of the Austrian Lloyd and Romanian shipping companies upstairs of which were used as their bureaus.15

The Ottoman era photographs of the hotel give the impression that the hotel was a three-storey building (the ground floor included) and that the second floor of the hotel might have been added later. In a photo by Rubellin the first name of the hotel Hotel M. Mille seems to be depicted as a relief on the front wall of the building above the first-floor balcony door and the large wall dressing just below the second floor used to be in the same style with those seen at the wall-endings. Also, the visibly different style of the third floor proves that the rising demand for hotels towards the end of the 19th century has obviously caused the extension of the hotel another floor upwards.16

The front facade facing the Cordon was laid out in a symmetric manner. The main entrance to the hotel was through an imposing arched portal, balconies jutted out from both storeys and finally the building was crowned with an arch pediment at the top. There were flat dressings applied to the front wall visible between two storeys. The fine ashlar texture of the external wall of the ground floor particularly stands out in the photographs that depicted the hotel. The axles upstairs were highlighted with plaster carvings. The exterior window frames of the first and the second storeys were in rectangular form. Whereas the first floor windows were decorated with French balconies and decorative plant-figure ornamental reliefs, the second floor windows were each decorated on the lower part with a layer of surface-dressing extending from one end to the other end of that part of the facade. The front wall was finished on the top with another thick layer of dressing, and above that, with a low wall along the edge of the roof a parapet. On the low wall was hung the big nameplate of the hotel.17 The side of the hotel that faced the Post Office Street was known to have looked less sophisticated.

With the help of the recently constructed Izmir-Aydın Railway and thus the proliferation of transport options into the hinterland of Izmir, in parallel with the incremental worldwide recognition of the excavations in Ephesus that went on at the time, there was an enhancement in the number of visitors to Ayasuluk (present day Selçuk, known and mentioned in public records in the 19th century as Ayasuluk). International travellers in particular, but also the Levantines of Izmir and enthusiasts of antiquities set out on organised tours to the Selçuk area. Being aware of all these events, it did not take long for the managers of the Hotel Huck to decide to open a new branch of their hotel at Ayasuluk.

This new hotel was named Grand Huck Ephese. One half of the shares of the hotel were owned by the Huck family and the other half by the Izmir-Aydin Railway Company.18 In terms of architecture, the Ayasuluk hotel was different than the original. In general, the building had a less elaborate masonry structure. It was two-storey tall and there was a defining line of dressing between the storeys. The entrance to the hotel was through a hipped roof porch. There was also a veranda on one side of the hotel. Today the building is still present in Selçuk. However, because the upper floor of the hotel was burnt during the Greco-Turkish War of 1922, it was restored and protected as a single storey building. It currently serves as a restaurant called Cafe Carpouza run by the municipality. The name Carpouza is said to be the name of the owner of another hotel in the area in late 19th early 20th century period.

Note: Further information on the Ottoman Post Office whose offices were with the Huck Hotel.

Ali Özkan was born in Tire in 1988, graduated from the Dokuz Eylül University Classical Archeaology faculty in 2010. In the same year at the same university he started his masters in this discipline. During this study he worked in the excavations of the classical sites of Phokia and Old Smyrna. Between 2010 and 2011he worked participated in the Selçuk city memory organised by the Izmir Selçuk Municipalities. He also participated in the digs organised by the Gazi University in Ovaören in the Capadocia region under the direction of Prof. Dr. Yücel Şenyurt. Starting from his high-school days Mr Özkan has been interested in Anatolian city planning and its interaction with their communities and in this discipline applying this analysis to the cities of the region in Ottoman and ancient times. In this speciality he has conducted studies on Tire and Izmir. His other published articles to date:

İzmir Kültür ve Turizm Dergisi Sayı 6: An Ottoman town minarets in Tire

İzmir Tarih ve Toplum Dergisi Sayı 7: Bir Osmanlı Kenti Tirede Minareler

Kubaba Dergisi Sayı 15: Arkaik ve Klasik Çağda Kaystros Havzası [Çağda Kaystros region in archaic and classical periods]

Ege Defterleri 3: Ephesos, Ayasuluğ ve Evliya Çelebi [The traveller Evliya Çelebi and Ephesus and Ayasoluk]

2. Cana Bilsel, Modern Bir Akdeniz Metropolüne Doğru (Towards a Mediterranean Metropolis), İzmir 1830-1930 Unutulmuş Bir Kent mi? (Izmir 1830-1930 A Forgotten City?) İletişim: 154.

3. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi, (A History of Izmir Hotels) Apikam: 1.

4. Çınar Atay, İzmir Hanları (Historic Commercial Buildings of Izmir), Apikam: 62.

5. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi (A History of Izmir Hotels), Apikam: 1.

6. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi (A History of Izmir Hotels), Apikam: 103.

7. Çınar Atay, İzmirin İzmiri (Izmir in Izmir), Esiad Yayınları: 195.

8. T.N.: The Bazaar.

9. Çınar Atay, Tanzimat tan Cumhuriyete İzmir Planları (City Plans of Izmir from the Reform to Republican Eras), Yaşar Eğitim ve Kültür Vakfı: 46.

10. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi (A History of Izmir Hotels), Apikam: 103.

11. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi (A History of Izmir Hotels), Apikam: 103.

12. Çınar Atay, 19. Yüzyıl İzmir Fotoğrafları (19th Century Izmir Photographs), Akmed Yayınları: 199.

13. Almanach Synoptıque A LUsage Du Levant (The Synoptic Almanac in the Use of the Levant), 1894: 93.

14. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi (A History of Izmir Hotels), Apikam: 103.

15. Çınar Atay, İzmirin İzmiri (Izmir in Izmir), Esiad Yayınları: 195.

16. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi (A History of Izmir Hotels), Apikam: 103.

17. Emel Kayın, İzmir Oteller Tarihi (A History of Izmir Hotels), Apikam: 105.

18. Ali Can, Eski Kartpostallarla Ayasuluğ/Efes (Ayasuluk/Ephesus in Old Postcards), Selçuk Kent Belleği Yayınları: 31.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|