|

Introduction and the Outline of the Research:

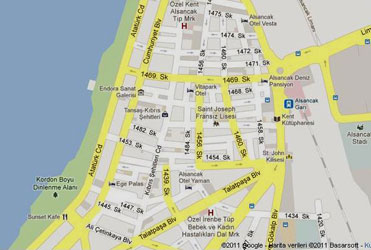

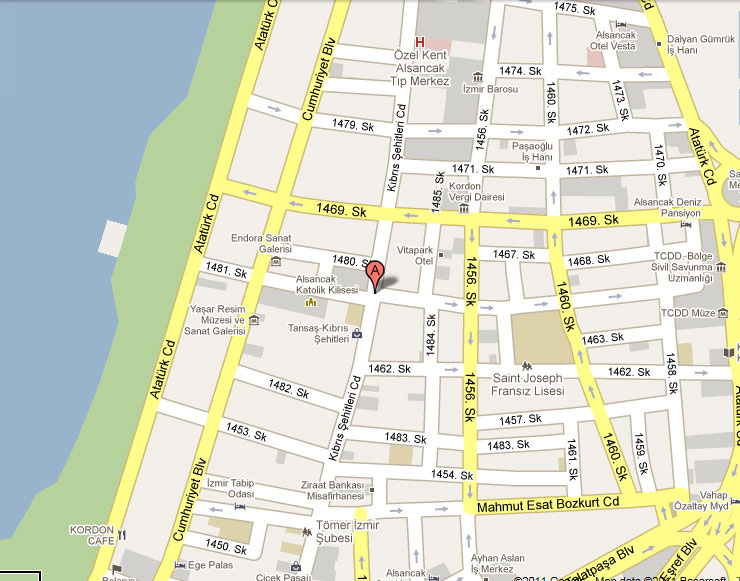

This article is based on the interview with Rinaldo Russo2, a Levantine gentleman from Izmir aged 65, recorded during an excursion with him on 1462 Street where he was born and spent most of his life, and serves as the initial outcome of a recently-started in-progress study on the property/ownership history of historic Punta (north-east Alsancak) houses located on multiple streets in the area (See map 01 below). The study will mainly employ the oral history method in acquiring its targeted data and the way the method is used in this particular piece was to have Mr. Russo exert anything he could remember about the houses regarding their former owners and tenants as we walked the street from end to end and passed by the houses one by one together with him. The interviewee group, henceforth, will not be limited to the Levantines but include grownups that own or once did or just rented at one stage in their lives any of the houses in question and/or know the neighbourhood well. The newest of the houses we are going to be dealing with is approximately 100 years old, therefore, one of our goals with this project is to go back as far as is possible in the history of these properties to find and bring out the least little piece of information about their past. Bringing to light such names, incidents and facts will no doubt form and help to explain the big picture of the gradual transformation (and, perhaps, whether that constitutes a pattern) of this underestimated urban space which belongs to a not too distant past. The question of property in the area has not been scrutinised too much so far, even though it is a relatively contemporary topic but probably due to the complexities the ontology of such a study might bring about. This infant study also aims to have collected by the end of its lifetime, enough data to be interpreted in various forms and ways in future studies. Before going into the details of the research question, it is necessary to note here that it is very likely, with the lapse of time, that this article and the future ones which will concentrate on the relevant streets in the area will/may see updates such as the addition of extra literature review and the results of the examinations of other source materials like deed archives, as well as further written/recorded testimonies or interviews of more than one people per article.

Background Information:

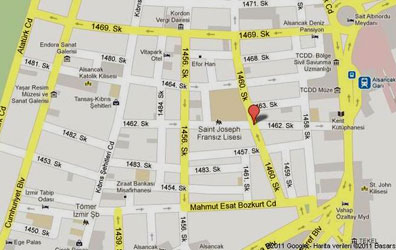

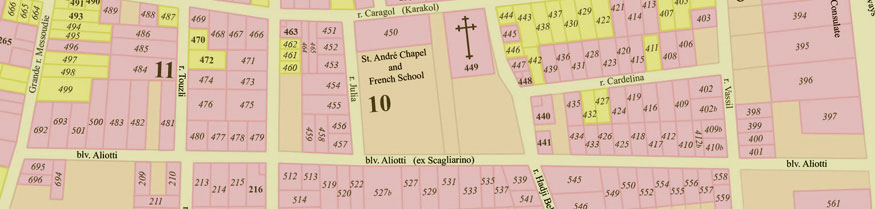

1462/Yüzbaşı Şerafettin Bey3 Street (according to reliable sources4 the street was known as Boulevard Alliotti in pre-1922 era5, named for Enrico Alliotti [1852-1912], a wealthy member of the notable Florentine family6 that moved to Izmir from Chios in 1820s and owned land in the area, as well as mansions in Karşıyaka, Buca and Bornova in the late 19th century7) where St. Joseph French School also situated, is one of the places that were spared the Great Fire of 1922, thus preserved its authentic physical structure against all odds until recent times, together with a number of intersecting streets and the vicinity that altogether formed the Punta and Bella Vista districts of Smyrna (present day Alsancak, formerly known as Mesudiye). (See map 02).

Map 01 |

Map 02 |

The majority of the houses built in this area in the late 19th century and lies between the Alsancak Railway Station (former Aydin Railway Station) and the Cordon, excluding todays newly built apartment blocks, are terraced houses of an eclectic eastern Mediterranean architectural style, variations of which can be seen in Chios8, Malta and various Western/Midwestern Anatolian trade towns (e.g. Çeşme, Urla, Ayvalık, Milas, Kula etc.), famous for the buildings stone or brick façade, stocky and narrow from the front, yet wide from the side figure, typical bow windows (cumba as locally known) and exterior ornaments.9 Though one can come across this type of row homes in several mid to high-income parts of Izmir (e.g. Karşıyaka, Basmane, Karataş and Göztepe), the oldest examples (hence the prototypes of modern urban architecture in Izmir) are found in greater number and density in Punta, not only because the first attempts of speculative land development, public housing and town planning10 in the city, in the sense we understand it today, were put into practice in the area beginning from the 1850s up to 1910s, as a consequence of and in parallel with the following factors: the first-time granting of the right to private property to foreigners and the Ottoman subjects in 185611 and that of land-owning in 186712 as part of the post-1839 Tanzimat reforms, the establishment of Aydin and Kasaba Railway Stations13 respectively, and the renovation of the harbour and the quay14 between the mid 1850s and mid 1870s that served as a huge catalyst for the accumulation of capital and development in the area15, as well as the areas proximity to Darağaç and Halkapınar - the industrial zone of the city, the explosion of population in the city in late 19th-early 20th centuries period due to post-war immigration and the enhancement of its capacity, as a productive port city, of attracting more and more population from all over the world, hence the inevitable emergence of the need for further housing, but also the fact that the interest in the then configuration in Punta had spilled over to the above-mentioned districts and helped the re/structuring of the existing (but partly destroyed, because of fires and earthquakes) and newly constructed neighbourhoods in a similar fashion (i.e. similar row houses built over speculative parcelling after the filling of the coastal zone like in the case of coastal Punta).16

As mentioned above, Mr. Russos narrative focuses particularly on the extent he knew about a number of houses located on 1462 Street: any names of the owners or tenants that left a mark in the history of the houses; whether those people are/were Levantines or not, and any memories concerning them if available. Having born in 1946, Mr. Russos effort of remembering covers the period between mid-1950s and the early 1980s. Though he was able to recall the faintest of detail for 16 houses in total that still stand on the street, there are approximately half as many that he could not remember anything about at all. There are two spots on the street where he said the persons he actually knew once lived, albeit with no hint of the existence of a former house. Dull apartment blocks stand on those spots today.

According to Mr. Russo, 1462 Street was filled thoroughly with Chios-style houses until late 1970s; however, due to a number of reasons that deserve further investigation, they fell into disfavour and came to be left to their fate at more or less the same time. As a result, the houses either got demolished and later concrete buildings began to appear on their places, or somehow managed to stand the test of time but with major deficiencies.17 It is only after the enactment of a law that foresaw the inclusion of such houses into the list of protected areas in Turkey18 that the demolitions of the houses came to a halt, Mr. Russo asserts, and from that point onwards began the second part of the story which is, unfortunately not treated in this piece, the social and economic account of the beneficial occupancy of the houses in the space of the last couple of decades.

Mr. Russo notes that prior to 1922 the houses in the area were owned mostly by the Levantines as the area was the former European/Frank quarter of the city, however, wealthy Ottoman subjects (notably the non-Muslims) could afford purchasing houses in the area as well. The profile of the ownership of the houses saw a dramatic change as more and more Muslim/Turkish names came into the scene with the beginning of the Republican era depending on the migrations within, from outside and out of the country up until today.

On 1462 Street:

Turning right from Kıbrıs Şehitleri thoroughfare and entering 1462 Street, the first building on the left (No. 1 and 3), which seems to be an altered old house is unknown to Mr. Russo, and the second house (No.7) which serves as a fish restaurant today used to be the house of Ali Kocatepes19 parents in the last mid-century. Kocatepes father Recep Kocatepe is said to be a sanitarian; he used to give injections to the sick. The pink house (No. 9) right next to the fish restaurant used to belong to the Serra Family who was known to be of Maltese origin.20. The ruinous house (No. 11) standing next to the pink house was inhabited by Abel Russo and his family. Mr. Russo adds: Thats the house where my cousins Pola and Iolanda grew up. The last house on the same row (No. 15), on the corner, used to be inhabited by a medical doctor, Hulki Cura, who had specialised in the diagnosis and treatment of ENT (ear, nose and throat) disorders and used to examine his neighbours frequently, as Mr. Russo points out. Though he cannot remember who could have owned the house before Mr. Cura, he states that Mr. Cura had a son named Hüseyin Cura, and the family delivered the house to the Board for the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage which now uses the place as their head office. There are three old houses along this line coming before St. Joseph School (No. 39) existing, and the first one (No. 33 - view internal images) being used as the office building of the Chamber of Agricultural Engineers, the second one (No. 35) as a pension and the third one (No. 37) is in private use today respectively; however, Mr. Russo was not able to identify any of them. After these houses comes St. Joseph School and across the school, the second one in the series of apartment blocks standing on the place of the former house of the Scaglarini family, as Cristina Bertamini reports.21 Toward the end of this row pops up a single old house (No. 51) in a bad state about which Mr. Russo could not report anything.

Below: Houses on the left side of the street seen from left to right

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||

|

|

|

On the right side of the street, beginning from the streets far end facing Kıbrıs Şehitleri Street, stands a restored old house (No. 2) where, according to Alex Baltazzi, used to live a lady called Mademoiselle Papanio and her mother22, and slightly towards left comes a number of apartment blocks in the middle of which remains the now-vacant lot of the demolished Tito house23 (No. 4). Slightly left, comes an old single storey house which is used as a restaurant today (No. 10 or 18). According to Mr. Russo, the apartment block (No. 20) used to be the former place of an authentic house of a Greek family. He continues:

I cannot remember the familys name but one of their female descendants is married to a Levantine gentleman called John. I cannot remember this Johns second name as well. They must be living in a house in back of St. Joseph School.

The next concrete block (No. 22) happens to be the place of the former house Mr. Russos parents have rented between the 1960s and late 1970s. He recalls the old times:

At the time that I graduated from college, my parents were living in a house right here. I was born in my grandparents house which is a few steps away from here. My parents have rented this house at one stage; therefore we had changed houses. I was working at a bank circa 1976, and I remember having stayed in this house together with my father. In the late 1970s the house got demolished. In the meantime my grandparents passed away, so we moved back into their house.24 Today, none of us live in that house. I rent it out.

The house (No. 32) standing on the right side of Mr. Russos parents former house, as far as Mr. Russo could remember, used to be owned by a single woman called Angèle who used to live in that house with her old mother.

Below: First set of houses on the right side from right to left

|

|

|

|

|

Below: First set of houses on the right side seen from right to left

|

|

|

|

|

After jumping to the other corner begins the line of ten row houses all of which still stand. As for the red house (No. 38) on the corner Mr. Russo could not remember much: A Cretan Muslim family used to live there who then moved to Buca. The family seems to have spoken mainly Greek, the language they must have learned in Crete, with their predominantly Levantine neighbours in the daily life of the 1950s Izmir. People living on this street used to speak also French and Italian, Mr. Russo adds. Next to the red house stands the former house of Derviş Onart (No. 40) whose wife was a Cretan refugee, where, according to Cristina Bertamini, the Saliba Family also lived.25. The house seems to be neglected for long but is not in ruins, like some of them in the area really are. After this house, one of the following two almost identical houses with dark green window shutters, the one on the right, is Mr. Russos grandparents house26 (No. 42); the house where he was born in 1946 and lived with his family until they had to move to the now-gone rented house toward the west end of the street. All along my childhood, we lived in this house, he says with a slight smile on his face while standing in front of the building, for a long time now its for rent. I trust its going to become a guesthouse in near future. The house next to it (No. 44) used to be Mr. Saki Kalyoncus (yet another Cretan family) house. And the very next house which serves as the guesthouse of Altay Sports Club today (No. 46) used to be occupied by a relative of Derviş Onart, Mr. Yahya Kerim Onart, who was an olive oil merchant.27

Below: Second set of houses on the right side of the street seen from right to left

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

|

Mr. Russo remembers:

I attended St. Joseph School on this street which was a stones throw away from our house; it used to take me only a couple of steps to get there. There used to be a kindergarten in our school back then; as far as I know there is not one anymore. I went to kindergarten, elementary and junior high school, all in the French School. I spent lovely years living in this neighbourhood. Alas, where is the old Alsancak, what happened to it? None of our old neighbours are alive today.

Turning back to the houses, next to the guesthouse stands the TURSAB (Association of Turkish Travel Agencies) building. (No. 48) According to Mr. Russo, this stone house which is for him the most beautiful house on this street used to be occupied by the Cassano family.28 Mr. Cassanos wife Berta Russo was my fathers cousin, he utters. The house next to the Cassano house used to belong to the Italian Penso family. It is used as the office building of a local organisation today (No. 50-2). I think the Pensos sold the house to them, Mr. Russo suggests. The house standing next to it seems to be in a fair condition yet still needs restoration. Alexandro and Angèle (née Cosentino) Bertuzzi used to inhabit the house (No. 54-6) but it originally belonged to Mrs. Bertuzzis mother.29 Mr. Bertuzzi used to work in the Italian Consulate. Mr. Russo remembers that the house had two doors and the couple used to use the left door as they lived upstairs and rented out the rooms downstairs. Next to the former Cosentino/Bertuzzi house stands a ramshackle building (No. 58-60) which seriously needs repair. Mr. Russo cannot provide any information about it. Turhan Tülis, an old resident of the neighbourhood reports that a lady called Martha Amati who gave violin lessons used to live in the first floor of the house. Her neighbour from upstairs, Binyamin Roditi and his family had rented and lived in the second floor of the house for 12 years covering the whole period of 1970s. Giovanni Giulietti states that at one time she was neighbours with Joseph Kalomeni and family. It is reported that a fire had broken out and the house got seriously damaged. According to the old residents of the street the house was owned firstly by Mariça Pugno, and after her passing away by her sister Jacqueline Servel.30 Ironically, the best-looking building of the street stands next to the worst-looking one: This restored two and half storey house (No. 62-4), according to Mr. Russo, was owned formerly by a Levantine and now belongs to a Turkish lady that he does not know personally. When I was younger, the house on the right to this tall house belonged to Alfred Simes (No. 66).31 Mr. Russo continues: I frequented this house many times when I was a boy. Rodney (Simes) was born there. We grew up together on this street.

Below: Third set of houses on the right side from right to left

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the corner against the former Simes house stands an old, single storey house (No. 72). Mr. Russo notes that a Turkish family used to live there years ago. The old residents of this street report that a Mr. Blackburn who gave private lessons to schoolchildren and ran the Hachette Bookstore that was situated across Gazi School with her sister Madame Odile used to live on this street and probably in that house.32 As we walk slowly toward the end of the street Mr. Russo repeats once again that the whole street used to be full of detached houses. Erkut Çobanoğlu, another resident of the area, denotes that the family physician Tevfik Sağel and family used to live somewhere on the right side of the street toward the far end of it facing Atatürk Street.33 While reaching the end of the street that looks to the premises of Alsancak Railway Station, we notice a free space on the right side that is now in use as a parking lot. Mr. Russo states that there used to be a famous hospital called Ege Hospital on that vacant place.

|

|

|

Baltazzi mentions in his 2011 memoir book the following people (some of whom previously mentioned in this article) as the old residents of this street but does not pinpoint the house locations: The Muzmuz, Gurassi, Kalomeni, Karakaş, Mentzen, Sponza, Micaleff, Scagliarini, Corsini, Cosentino and Simes families; his classmate from St. Joseph College, Jak Saliba and his family, Mademoiselle de Sain who used to give English lessons and the dentist Ajlan Tuna.34 Another veteran resident of Alsancak, Giovanni Giulietti, noting that he has spent all his childhood in 1462 Street, mentions the names of Rodney Simes, Alfio and Rinaldo Russo, Alin and Alp Kalomeni, Cassano Family, William Toctan, Ninetta Scagliarino and Pierre Berovitch of Bulgarian descent as having lived there alongside him and his family.35 Bülent Moralı, author of two memoir books about the life he spent in Alsancak as well as a society figure, makes mention of the following families and people as having lived in the street throughout the last quarter of the last century: Gürassi, Papi, Vitel, Russo, Kalomeni, Apagno, Karakaş, Akkalay, Paradiso and Alevo families, Oğuz Kaynak, Rauf Kalkay, physician Hulki Cura, dentist Münir Tuna, former Mayor of Konak Muzaffer Tunçağ, Professor Hasan Olalı, olive oil merchants Mehmet Emin Tan and Yahya Kerim Onart, Şerif Mühürdaroğlu, Ahmet Burkut, commander Fatih Taşgın and his own parents.36

|

The Pervititch is from 1923, but is based on older maps, especially on the Goad insurance map from November 1905. The Bon map is from 1913. The Bon map was used only for cross-checking, street names etc., as it is not so accurate. The numbers were not house numbers, they were plot numbers existing already in the 1905 map. The bigger numbers are block numbers, and they are common in all maps from 1905 to 1923 information courtesy of George Poulimenos.

Conclusion:

Given the facts that this article is the first outcome of a research that is conducted in Punta neighbourhood and that will look into further streets other than 1462 Street, and that it might see certain changes (i.e. updates and edits) in time, it may be early to make generalisations; however, certain conclusions can still be drawn from the data obtained in this particular tour with Rinaldo Russo and from the oral and written testimonies of different source people. Besides, some of the observations of this article are likely to be re-encountered in the coming up street-studies. To name a few: considerable amount of the houses in the street tend to be either completely gone or are in a ruinous state. Very few of the remaining and restored houses are used for the purpose of living in and the majority of them are used rather for business or other professional purposes. While such houses on 1462 Street are mainly used as the office or lodging buildings of public or private organisations, this cannot be generalised to the overall area as, for instance, on some streets, almost all of the houses of the kind serve as the same type of business establishment (e.g. café/bar.) The streets in the area that are very close to one another can still have different dynamics and qualities and show different aspects and outcomes. Thirdly, as of Mr. Russos personal interview, it looks like there is not a single non-Muslim native of the city still living on 1462 Street, and even the Muslim owners of the houses (majority of who tend to be of Cretan origin) seem to have left the street (maybe even the area) by means of renting out or selling the houses to the new residents of the street. Those (ex?) owners and tenants of the houses who seemingly lived there throughout the last century together with the members of the Levantine community who historically belonged to the area, consisted partly of the refugees who settled down in Punta (as well as in the other parts of Izmir and its environs) due to the population exchange of 1923 between Greece and Turkey and the follow-up immigration flow of more Muslims from the Balkans into Turkey and Izmir37 and a small number of Jews who exemplified an intra-city migration, on grounds that this formerly predominantly Christian part of the city historically could not have attracted many Jewish residents during the Ottoman period. Fifthly, a massive level of concretion is observable on the street which proves to be an example of irregular urbanisation in the area. While some of the old houses seem to be neatly restored, a handful of others are on the verge of collapsing down (the situation is not better in the nearby intersecting streets in that respect). The process of the changing hands of house ownership experienced arguably twice in the street (firstly in the 1920s, due to the tremendous changes the city went through because of wars, and secondly after the 1950s which has continued until today) has with no doubt contributed to a structural, socioeconomic, political and cultural upheaval in the zone38, and the comparative decrease in the areas value which needs more explanation in terms of parameters other than those assumed here (e.g. house rent prices, a socioeconomic profile of the streets inhabitants and more.) This article has tried to illustrate the historical urban origins of 1462 Street and its socio-historical progress through the lens of its old residents (owners and tenants) of the historic houses located on it and the urban planning practices concerning the houses well-being, and in that regard, sought to understand the extent the houses were legally protected and give an insight into the probable effect of the state (e.g. durability, purpose of usage etc.) the houses enjoyed on the actual physical appearance of the street in a wider urban context. Oral interviews and personal narratives have largely been used to qualify and justify this framework. While being aware of the risks of fallibility and bias this degree of orality and individuality might cause, and on the other hand there is a speciality and uniqueness about such personal accounts and also the hardness of reaching legal and/or private documents, the fact that the data gathered from various oral and written civil sources treated in this particular piece did not bring forth great clashes of information proved to be a satisfactory enough reason for the author to consider them to be the primary driving force of his analysis.

|

2 Interview date: October 27, 2011.

3 Lieutenant Şerafettin Bey: One of the leading commanders of the Turkish troops that entered Izmir on September 9, 1922, to put an end to the Turkish War of Independence. Şerafettin Bey and his troops fought the resistance fighters until they reached Konak, the imperial centre of the city, to hoist the Turkish flag at the governments office, which was done, according to the Turkish nationalistic historical discourse, by a wounded Şerafettin Bey. He has been a national hero ever since.

4 Enrico Aliotti, 2011, Some Notes about Aliotti Family, Levantines from the Past to the Present, Ed. Fikret Yılmaz, Izmir: Izmir Chamber of Commerce, 231-233; Fabio Tito, personal interview, Levantine Heritage, November 2005, Web, accessed on 10 November 2011.

5 Apparently, yet the reason is unknown to us, the street was known as Blvd. Scagliarino before it was called Blvd. Aliotti. See map 03 and footnote no. 10 down below.

6 Mustafa Demiralp, 2006, Comparison of Turkish and European Quarters of Izmir at Nineteenth Century Masters thesis, Istanbul Technical University, 59.

7 Alex Baltazzi, 2011, Alsancak: 1482 Sokak Anıları (Alsancak: Memories from 1482 Street), Istanbul: Heyamola Yayınları, 62-3. Baltazzi states in the same book that a member of the Aliotti family once told him that the Aliottis never actually lived on Boulevard Aliotti (p. 42).

8 Although there is a popular belief that the reason why this particular type of house is named after Chios is because the civil foremen who worked during their construction were known or believed to be of Chios origin, Çınar Atay argues that it was rather because those who resided in such houses were wealthy trader families from Chios who moved to Izmir especially after 1838 (the year when the Ottoman state granted foreigners the right to trade individually in the Ottoman country), and the style had become very much the trademark architectural style of the 19th century in the area. For more about the former argument and how the same houses later came to be known as Greek Houses (Rum Evi in Turkish Rum/Roman standing for Anatolian Greek) see Alex Baltazzi, 2011: 72-3. For the latter argument and a fuller discussion about the architectural characteristics of a Chios-style house, see Çınar Atay, 1998, 20. Yüzyıl Başında İzmir (Izmir at the Beginning of the 20th Century) in Osmanlıdan Cumhuriyete İzmir Planları (From the Ottoman to Republican Periods: City Plans of Izmir), Izmir: Yaşar Eğitim ve Kültür Vakfı, 18-9. Architecture historian Doğan Kuban asserts that it was minority (non-Muslim) architects and workmen who built those houses which he claims to be the representative example of the domestic architecture of the area at the time, whereas large buildings and estates were built mostly by their foreign counterparts. Doğan Kuban, 1972, İzmirin Tarihsel Yapısının Özellikleri Ve Korunması İle İlgili Rapor (A Report on the Qualities of Izmirs Historical Structure and How to Preserve It) in Kuban, 2001, Türkiyede Kentsel Koruma: Kent Tarihleri ve Koruma Yöntemleri (Urban Protection in Turkey: Histories of the Cities and the Ways to Protect them), Istanbul: Tarih Yurt Vakfı Yayınları, 100.

9 For more about the eclectic character of the Chios-style house and its place in the coastal Mediterranean and Aegean architectural context, see Şeniz Çıkış, Modern Konut Olarak XIX. Yüzyıl İzmir Konutu: Biçimsel ve Kavramsal Ortaklıklar (The 19th Century Izmir House As a Modern House: Stylistic and Notional Commonalities) METU JFA (February 2009): 212; 220-21.

10 An Italian engineer called Luigi Storari was assigned in 1851 by the local authorities of Smyrna to create the city plans of Smyrna. Both Storaris 1854-1856 plans and the one made in 1876 by Lamed Saad prove that the parcelling of Punta had already started by the time each plan was made and the prospective land owners of the area were going to name certain places in this popular neighbourhood after their names like in the cases of Boulevard Aliotti and the Mölhausen Square. For more about these city plans, see Cânâ Bilsel, 2008, Modern bir Akdeniz Metropolüne Doğru (Towards a Modern Mediterranean Metropolis) in Izmir 1830-1930: Unutulmuş bir Kent Mi? [Original title: Smyrne, la ville ou oubliée? (Smyrna, the Forgotten City?)] Ed: Marie-Carmen Smyrnelis, Istanbul: İletişim Publishing, 143-161; Rauf Beyru, 2011, 19. Yüzyılda İzmir Kenti (The City of Izmir in the 19th Century), Istanbul: Literatür Publishing, pp. 61-76.

11 Atay, 1998: 13.

12 İlhan Tekeli, 1992, Ege Bölgesinde Yerleşme Sisteminin 19. Yüzyıldaki Dönüşümü (Transformation of the Settlement System in the Aegean Region in 19th Century) in Üç İzmir (Three Izmirs), ed. Şahin Beygu, Istanbul: Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 133 (125-141). Same article also available in Tekeli, 2011, Anadoluda Yerleşme Sistemi ve Yerleşme Tarihleri (The Settlement System in Anatolia and the Dates of Settlement), Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, 178-201. Henceforth Tekeli 1992.

13 The construction of both railway lines had been completed by 1866. See Tekeli, 1992, 132.

14 The quay was built between the years 1868 and 1872. Kuban, 74.

15 There is a considerable amount of scholarly work in Turkish that looks into the critical juncture in the history of the city which is, in this case, to put briefly, the period of transition process to integration into the European capitalism structure on regional scale and its local repercussions on a spectrum of social, political, economic, cultural factors to name a few: the loosening of the power of Ottoman bureaucracy over foreign enterprises, industrial and agricultural production and the changing means of trade, transportation, communication, education, housing etc. To name just two remarkable examples of this literature, written, respectively, from a sociological and a Marxian political economy perspective, see Mübeccel Kıray, 1972, Örgütleşemeyen Kent: İzmir (The City That Could Not Become Organized), Istanbul: Bağlam Yayınclık; Orhan Kurmuş, 1974, Emperyalizmin Türkiyeye Girişi (The Import of Imperialism into Turkey), Istanbul: Yordam Kitap.

16 For a fuller discussion about this spill-over effect, see Çıkış, 227 and Bilsel 2008. Also, for more about the correlation between the demographic processes and urbanisation in the area in late 19th century, see Tekeli, 1992, 136-38 and Çıkış, 219-228.

17 An architecture scholar sees the 1950 municipal development plan of Izmir, which was the winner of the competition organised with this purpose, as the starter of the process that led to massive concretion particularly on the Cordon, however, her remarks can be generalised to include 1462 Street and the entire Alsancak as far as the destruction of pre-1922 houses are concerned. The fact that the plan did not foresee any protection regarding old buildings must have facilitated the occurrence of the abovementioned future actions, Gülnur Ballice argues. Secondly she points out the Condominium Act of 1965 which allowed the construction of 3-4 storey apartment blocks on the 1st and 2nd Cordon Streets. In time, 7-8 storey blocks came to be easily built by way of pointing to a precedent. As a result, between 1950s and early 1980s many houses as such got demolished and turned into apartment blocks, often happened on the very same plot, instead of merging plots, which culminated into massive walls of concrete that serve as apartment blocks. See Kordonu Kim Yıktı? in İzmir Life, October 2009: 32-3. It is very likely that a similar story was the case in 1462 Street. For a critical analysis of the business of constructing and then selling buildings in Punta after 1950s and the role of such legislative fait accompli, see İlhan Tekeli, 2001, İzmir İçin Orta Boy Açıklama (A Medium Size Description for Izmir), paper presented at a meeting held to celebrate the Centennial of Izmir Clock Tower on September 1, 2001, in Anadoluda Yerleşme Sistemi ve Tarihleri (The Settlement System in Anatolia and the Dates of Settlement) 2011, Istanbul: Tarih Vakfı Yurt Yayınları, 327-8. Another architecture scholar Emel Kayın emphasises also the importance of liberal policies carried out by the authorities, migration from rural to urban areas and the rapid (and irregular) urbanisation in the area (Izmir Life, p. 33). And another architecture scholar, Çınar Atay, emphasises the role of economic problems in addition to the fact that the legal procedures are weak and that there is not many functioning financial mechanisms to protect such urban areas. According to his analysis, the areas where the Punta houses are erected imply large values of unearned income, so the idea to destroy them and then build apartment blocks always had certain rationality from the house owners point of view that had to rent their houses for reasonable prices (while they could make more money some other way). Another factor Atay suggests us not to underestimate is that those houses were originally built for the use of 8-10 person families and the 4-person family of modern times was/is not able to adjust to the ontology of such houses, nor were/are wealthy enough to cover the repair costs. In sum, all led to the decay and/or degeneration of the houses. And one last problem Atay points out is the necessity to find a new way/form of employing these houses so as to use them the best way. Çınar Atay, 2001, Kültür ve Tabiat Varlıklarını Koruma Olgusu: Yasal Gelişim Süreçleri, Tanımlar, Uygulamalar (Protecting Cultural and Natural Heritage: Processes of Legal Development, Definitions and Practices), Izmir: Izmir Chamber of Commerce, 21. Kuban argues (1972:52), on the other hand, that it is rather a cultural than an economic problem protecting the historic environment. He wrote back in 1972 that the societies who were exposed to cultural changes had to start over again denying some of the features of their traditional culture so as to adapt to the ways of modern living more successfully. The Turkish society was one of them, and that brought forth the wide understanding in society that anything Western held a symbolic status and meant to be about modernity and innovation. The symbolic status of new materials and looks surpassed those of what is old and traditional, and this led to severe losses in cultural and historical continuity/sustainability. This also evokes, arguably, the thought that the historic heritage in Turkey with certain western quality somehow appears to masses as being foreign/alien or not Turkish-enough to be considered worth taking care of, therefore gets more likely/open to be neglected and let perish.

18 The oldest legislation in regard to the protection of antiquities in the Republican Turkey dates back to 1973 (the Antiquities Law, Act No. 1710). The next enactment in the same fashion, dating 1983, was called the Law on the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage (Act No. 2863) which saw three amendments further in 1987 (Act No. 3386), 2004 (Act No. 5226) and 2009 (amending the law in accordance with the Real Estate Tax Law). The 1987 Amendment established also an institution, the Regional Board(s) for the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage in Turkey. While the Act No. 2863 made mention of the term historic urban area, it was only in 1999 that the condition to take into account the protection of historic urban areas in city development plans was going to be laid down. See Atay, 2001, 3-22; Melike Z. Dağıstan Özdemir, Türkiyede Kültürel Mirasın Korunmasına Kısa Bir Bakış (A Short Look at the Protection of Cultural Heritage in Turkey), The Planning Journal by TMMOB, February 2005: 20-25; Hergüner Bilgen Özeke, Turkey: Regulatory Developments in the Turkish Real Estate Market, Mondaq, 23 April 2009, Web, accessed on 11 November 2011. The Punta area was proclaimed an historic urban site and taken under protection in 1976. Individual houses in the area were registered as historic buildings for the first time in 1977, and the same practice was carried out in 1980 and 1984. See Deniz Özkut, 2005, 62 in İzmir Mimarlık Rehberi (A Guide to Architecture in Izmir), 2005, ed. Deniz Güner, Istanbul: Mimarlar Odası İzmir Şubesi. In coherence with Mr. Russos statement, the houses seem to have fallen under the scope of the legislation to protect historical sites in the early 1980s, throughout which the law (2863) was going to be amended twice. Atay points out (2001:22-3) that there is not a certain inventory of the cultural heritage in Izmir and the attempts of locating and registering them take place on an arbitrary basis (e.g. turning blind eye on the demolition of unregistered confiscated buildings or the fact that the Clock Tower in Konak was registered as an historic monument only in the 1990s), and that there is a huge need of institutionalisation of the practices in the same field.

19 He is a Turkish popular music artist who is famous for the records he released between the 1970s and 1990s.

20 The Maltese Papi Family seems to have resided in the same house as well. Baltazzi, 63.

21 Personal communication, January 20, 2012.

22 2011: 63.

23 Tito descendant Fabio Tito says that the first owner of the former house was Giuseppe Tito. Following Mr. Titos death in 1976, his son Umberto Tito, one of his five children, lived in the house for while before its demolition. The land still belongs to the family. For more information about the Tito family and the photo showing the Tito house in its ruinous state before demolition, see Tito, op.cit.

24 The house numbered 42 on the same street.

25 Personal communication, January 20, 2012.

26 This house called the Russo/Cosentino house originally belonged to the Cosentino family and after Mr. Rinaldo Russos mothers (née Cosentino) death, must have passed to her children who were Russos. As such, there used to be a house across the historic Alsancak Police Station building which was called the Russo house and was more Russo in essence for that matter. The Russo House is destroyed and now stands on its place the Dalyan Office Block. Personal communication with Rinaldo Russo and Cinzia Braggiotti, January 8, 2012.

27 Seemingly, there is a vocational school for girls in Çeşme (Izmir) named for Yahya Kerim Onart.

28 Baltazzi also mentions his admiration of this house in his 2011 book and notes that the decorative plaster ceiling ornaments of the house were maintained by a Levantine from Karşıyaka, Mr. Pierre Murat. p.65.

29 Personal communication with Rinaldo Russo and Cinzia Braggiotti, January 8, 2012.

30 Çocukluğunu ve Gençliğini Alsancakta Geçirenler Sayfası (Those Who Spent Their Childhood and Youth in Alsancak) In Facebook (Group Page). Accessed on 30 November 2011. Henceforth CGAG.

31 Chances are the Simes Family also/or lived in the house no. 62-4. Source of information: Marina Corsini, personal communication, January 13, 2012.

32 CGAG.

33 ibid.

34 Baltazzi, 65-6.

35 CGAG.

36 Bülent Moralı, 1999, Puntadan Alsancaka: Alsancak Tarihine Kısa Bir Bakış (From Punta to Alsancak: A Brief History of Alsancak), Izmir: self publication, 15-7; Bülent Moralı, 2005, Puntadan Alsancaka, Alsancaktan İzmire 2 (From Punta to Alsancak, from Alsancak to Izmir 2), Izmir: Kelepir Yayınları, 71-3.

37 Tülay Alim Baran, 2003, Bir Kentin Yeniden Yapılanması: İzmir 1923-1938 (Reconstruction of a City: Izmir 1923-1938), Istanbul: Arma Yayınları, 142. Baran also notes that in 1930, 91.123 out of more than 100.000 immigrants/refugees had been accommodated in and around Izmir (p. 143). In central Izmir, Karşıyaka, Tepecik, Alsancak, Karataş, Göztepe and Karantina were among the districts that those people were placed in (p.134-5). It was aimed at the time that they were given the houses and workplaces of the then parted Greeks and Armenians (properties known as emval-i metruke in Turkish) in exchange for what they lost by having to leave their hometown and countries. We do not know clearly whether any of the Chios-style houses in Punta were subject to emval-i metruke, meaning, whether any of them were Greek or Armenian properties. Apart from the fire zone that was completely destroyed and gone under reconstruction, the properties that were put up for sale and sold out in Depression years which belonged to the Greeks who had left Izmir after 1922, the urban planning scholar Emel Göksu reports, concentrated mostly on the Mesudiye (Alsancak) and Güzelyalı axis. Emel Göksu, 2010, Kentleşmenin Kurucu Öznesi Olarak Kriz: 1929 Buhranı ve İzmirde Mekânsal Dönüşümün Yeni Aktörleri (Crisis As the Founding Agent of Urbanisation: The Great Depression of 1929 and the Emerging Actors of Spatial Transformation) in Değişen İzmiri Anlamak (To Understand the Changing Izmir) ed. Deniz Yıldırım & Evren Haspolat, Ankara: Phoenix Yayınları, 146 (135-171). Even if we assume that some of the old Punta houses were owned by Greeks and Armenians, it is still not easy to deduce that they were handed over directly to the Muslim immigrant/refugees (or by way of putting them into debt), as Baran points out many times in her work the difficulties, sometimes even corruption and the lack of functioning systematisation in the distribution of these properties was the case (105-166; 206-7). Therefore, the Cretan inhabitants of the abovementioned houses could have settled down in the neighbourhood in mid 1920s or much later, irrespective of the plan of accommodating the immigrants in the early years of modern Turkey.

38 Emel Kayın, 2010, Mekânsal ve Sosyoekonomik Ayrıksılıklar Geriliminde İzmir: Küresel-Yerel Fenomenler (Izmir in the Tense Context of Spatial and Socioeconomic Exceptionalities: Global-Local Phenomena) in Değişen İzmiri Anlamak (To Understand the Changing Izmir) ed. Deniz Yıldırım & Evren Haspolat, Ankara: Phoenix Yayınevi, 348-9 (337-60). Kayın sees the period covering the wartime, the fire of Smyrna/Izmir and the founding of the Turkish Republic as a breaking point in the history of the city. She also asserts that a series of critical moments in the following decades led to the emergence of a civic identity, conflicting in terms of spatial and socioeconomic exceptionalities, enjoyed by many of the dwellers of the city mostly among the middle-class.

|

|

Modern map of the area View above thumbnails as a gallery | view old images of wider Alsancak and Bella Vista area | read interview with Alex Baltazzi, author of Alsancak |