Ephemera

David Offley letters

The writer of these letters, David Offley, (1779-1838), was born in Philadelphia; He served as 1st Lieutenant in the 10th U.S. Infantry, at Carlisle Barracks, Pa., 1798-1800; Established the first American commercial firm in Turkey, at Smyrna in 1811, and was the chief U.S. merchant in Turkey; U.S. Commercial Agent to Turkey; Negotiated the first U.S.-Turkey commercial treaty in 1830, and in 1832, was appointed by President Andrew Jackson, 1st U.S. Consul at Smyrna.

The College of William & Mary, in Williamsburg, Virginia, holds a collection of Offley family papers from 1826-1916, though little is of David Offley himself, and the collection starts eight years after this letter. In the span from 1811, when Offley arrived in Turkey, to 1820, approximately eighty American ships stopped at Smyrna, selling cotton goods, tobacco, gunpowder, bread-stuffs and rum. In return, American merchants picked up such Turkish exports as nuts, silver, raw wool, and hides, and participated more and more in the opium trade between the Near East and China. After 1815 the U.S. government sought to assist commerce through a naval squadron in the Mediterranean, based at Minorca. During the 1820s Henry Clay of Kentucky, who favoured the Greek drive for independence from the Ottoman Empire, spoke vehemently in the House of Representatives against pro-Turkish attitude of commercial leaders in the U.S.. During the Greek war, American opinion was divided. President James Moore in 1823 came close to recognition of Greek independence. But on American soil, the government remained aloof while commerce with the Ottoman Empire expanded. The chief merchant at Smyrna, David Offley, after 1811 led these American businessmen. Offley’s Philadelphia firm controlled about 30% of the goods exchanged there.

David Offley (1779-1838), was an invaluable and foremost contributor to American commerce in Turkey, having established the first American commercial firm, Woodmans and Offley, in Smyrna (Izmir) in 1811, then becoming chief U.S. merchant in Turkey, and U.S. Commercial Agent to Turkey from 1823 to 1832. He further negotiated the first U.S. commercial treaty with the Ottoman Empire in 1830, and in 1832, was appointed by President Andrew Jackson, first U.S. Consul at Smyrna. He remained Consul until his death in 1838. Three of his sons, Richard Jones Offley (1800-1842), John Holmes Offley (1802-1845), and David Washington Offley (1805-1846) lived with him in Constantinople, all of which are mentioned by name in this letter.

U.S. diplomatic interaction with Turkey dates back to the days when Turkey was known as the Ottoman Empire. Though trade had been ongoing for some time led by Offley's enterprise, the first formal act of diplomatic engagement and recognition between the Ottoman Empire (Turkey) and the United States occurred on February 11, 1830, when a U.S. negotiating team comprised of Captain James Biddle, David Offley, and Charles Rhind presented their credentials to the Turkish Minister of Foreign Affairs. A treaty of navigation and commerce between the two nations was successfully negotiated, and diplomatic relations were subsequently established. The relationship was maintained until U.S. entry into World War I on April 20, 1917.

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, September 28, 1815, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley, at Philadelphia, Pa.

The content includes that not many ships from the U.S. have arrived at Smyrna since the Peace was declared (the treaty ending the War of 1812), and the great length of time it takes for letters from the U.S. to reach him; Writes of his business prospects, and his having established a business to ship wine, and his feeling that it is his destiny to remain in Smyrna for a long time (in fact, he stayed there until his death 23 years after this letter was written). He also writes that he is anxious for 2 of his sons, Richard & David, to come from the U.S. and join him in Turkey, and his plans to set them up in business. Of his 3rd son, Holmes, he encourages him to remain in the U.S. and pursue his intention of learning to become a farmer, but if he changes his mind and wants to be a merchant, he would be happy for him to come to Smyrna as well.

Includes:

“Your kind & affectionate letter of October last, came only to hand last month, and notwithstanding the frequent arrivals at almost every port in the Mediterranean, I have no letters from Philadelphia later than March. I am however, well convinced that no fault rests with my dear Sister. The last letter I wrote was by Mr. Hazard, and which I presume will not be received long before this.

I still remain in the same opinion that my destiny is to remain some years longer in this Country, for on every consideration, I know of no place where my interests would be more advanced than here. I wait most anxiously to hear from you an answer to my letters of December & January last, wherein I requested my dear sons, Richard & David, might be sent to me. Indeed, I begin almost to look for them with impatience... what a joyful moment it will be to me when they arrive. My dear Holmes, who I hope always remains in the disposition to become a farmer, I hope may be placed with our brother... If however, he changes his mind and inclines to be a merchant, I shall then send for him to be brought up in my counting house. My dear little daughter can be in no place so much to my satisfaction as where she now is. All this I have repeated in every letter I have wrote since last December, in case my letters may be lost.

We have only had one vessel to our address since the peace, but I am in hopes now that all difficulty appears removed; that our business may revive, and that when Richard shall be of an age suitable to leave here, that I may be able to furnish him a good Capital, and return home with the means of enjoying, if possible, some peace in my old days. This is my wish, but I know too well the uncertainty of this world to say this is the plan from which I shall not vary.

I have lately established in this place, a house for the commerce in wine, and which at this moment holds out most flattering prospects. I trust by next Summer I shall have some cargoes ready to ship to Philadelphia, & should they succeed according to what I call most moderate calculations, I shall not require many years to enable me to purchase the long contemplated farm in our corner, of which I yet hope to lay my bones.

Mr. Hazard, who by this time I hope you have become well acquainted, will inform you the dull life I lead in this place. My family still consists of myself, servant, & an old cat, so that when at evening I return home, it may be truly said I have retired. I promise myself great pleasure in the company of my dear boys, & do not despair of seeing them... next month. When they come, I shall add two chambers & a House Keeper to my establishment.

I have had some thought of breaking up housekeeping, and accepting an invitation I have had from a most agreeeable family to reside with them, and where my children would have the opportunity of being in the best company the place affords. But on reflection, I have thought it would better suit my temper to command my servant & old cat, than to be in any manner dependant on the will of others.

I think much of you, my dear sister, and fear my determination to remain here will not be pleasing to you, but what can I do. I am not able to retire from business in justice to my children, and as a merchant, there is no place where my prospects would be so good as here. Then, let me ask you candidly, ought I not to stay. I have a few (very few indeed) friends who I wish to see. Was it not for them, what inducement have I to live in America. Certainly the recollections which Philadelphia must always present to my mind are not of the kind to add to my tranquility or happiness.

Kiss my dear children for me, and tell them never to cease loving me. My dear darling little girl, do not let her forget me...

I have put off writing this letter until too late. They now wait for it, or I would tear it up ten thousand times, it says so little of what I think; so much is so illy expressed...”

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, July 10, 1818, from David Offley, to his sister, Miss Mary Offley, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter has red “NEW-YORK” cds, red “SHIP” handstamp, and manuscript “27” rate. The NYC postmark is dated Sept. 29, indicating that the letter took over two and a half months to reach the U.S. There are 2 manuscript notations on the face of the cover, which read “House shut” & the initials “JR”, which are likely made by a postal employee, referring to the Offley house being shut (which they did in the summer & through Sept. during the Yellow Fever season in Philadelphia, spending those months in the country, which was considered safer than the City).

He writes a lengthy discussion of his opinion of the religion of Islam, which in his opinion, Christians could learn from, and which he is somewhat tempted to convert to. This must have come as a shock to his sister, a devout Quaker (their father was a Quaker minister). He also writes of his 3 young sons (Richard, Holmes & David), who came to Turkey to live with him, and of his young daughter he left behind in the care of his mother & sister in Philadelphia. He writes of his business in Turkey, travels to Constantinople, and of the increasing notice the Turks are taking of Americans.

Includes:

“A few days since my return from Constantinople, I had the pleasure to receive your letters January 12, & No. 3, 2d mo. 21st [Feb. 21st], the first of which had come to hand for some time, & I fear you will remain some time without hearing from me, as there has been few opportunities of late for writing.

The last I wrote was...on May 4. In that letter, I told you the pains which had been taken to make me a Catholic, while you at the same time believe me to be a Turk - much as I admire their religion & education as but to ensure happiness & content[ment] in this world. Still I have too much respect & even veneration for a few of you, to do an act which would forfeit the good opinion & love I hope always to retain - besides which I know it wold be impossible with my education & habits to enjoy the peace & happiness I see them more fully in possession of than any other people I have ever been among. To believe in God, that there is but one God, & that Mohamet is his prophet, is their whole creed. Their prayers might be cited as examples to Christians as most perfect...on the Goodness of God; that he never punishes but thro’ love, and as he knows what is best, that no attention may be paid to the longings of their hearts, which are so often after bad. A good Musleman will see himself bereft in one moment of wife, children & fortune, and bear it above what we can suppose human nature capable. When he regards it as a punishment of God, he is then consoled in the assurance of his love.

During my journey to Constantinople, I had frequent opportunities of viewing these people at their homes. Owing to heavy rains, I was obliged to take an unusual road, which led me to villages little frequented by Christians. I spend several very happy days in some of them. I never have witnessed less illusion, or more truth in my life - hospitality that astonished even me - myself & attendants were fed & lodged in the best manner. At one village, I had a visit from the Iman, or Priest, & a long conversation with him. More noble, high & exalted ideas of Providence I never had. At Constantinople, I received from several Turks of high authority, the most unusual & flattering attentions; so much so, as to induce the believe among all Christians I could be nothing less than an ambassador from the ‘New World’. The name of American is becoming a title of respectability, & ere long, to be a Citizen of the Republic of America will excite as much attention as ever was received by a Roman.

With my Turks & Turkish principles, I am like to fill up my letter, & perhaps to a good Christian, so much praise of Infidels may may look too much like Infidelity.

How much I am pleased with what I hear of my darling Child....I am much pleased also to hear of her progress and that you have found a good school for her. I hope ere long she will begin the study of the French language. As to Music & dancing, if it could be so managed, I should like her to be learnt, but I would by no means give up the solid advantages she enjoys in my dear Mother’s... for even these agreeable amusements. To a Boarding school. I am no way desirous she should ever go...

Much, my beloved sister, do I wish to see you, much do I wish to enjoy a little of that rational happiness I should be so certain of finding in the old house in Front Street; but depend on it, our actions are always governed by circumstances over which we have no control, several of which appear to make my removal from this country difficult. My commercial establishment has become too valuable to be slightlyl abandoned by a father of three sons. This establishment promises an easy entrance for my children into the world. The best prospect I see for my children in in this country, and these are most desirous considerations, are they not. Lay aside for one moment, ‘enthusiasm’, & judge as a ‘plain matter of fact’ woman, and you will say I am right. Much do I desire to see America, but still that rose would not be without its thorns. I am not happy even at this distance from the scene of my disgrace & unhappiness, the view of scenes which would ever moment recall recollections to make the blood boil in my veins, would conduce to nothing but more complete misery. How well I feel, Mary, that my heart was never made to exist as it now does. When I return to a house I may call elegant, furnished with everything which certain luxury...to make life agreeable....I feel shut up from the world as if I was the only creature in it. Less of that enthusiasm of character you admire would be most desirable for me once more. Patience, patience, patience.

Richard [his son], has recovered his health, and is much more lively than ever I have known him. He is nearly as tall as I am & would pass well for a young man of 23 or 25 years. It is in contemplation for him to go shortly to Constaninople, where probably he may remain some time. We do much business in that place, & I may be able to make arrangements which will be highly advantageous to him. Holmes [another son] will come into the Counting House this year. He continues much undersize. David [another son] goes on very well - grows astonishingly, & I predict one way or another will make a figure in the world...

Well, my dear little sister, when is all these Beaux visits to finish. When do you mean to settle down into the quiety & domestic wife. Whenever you find one who you love better than Mother, Brother or Sister, do not let him escape...”

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, June 20, 1820, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley, at Philadelphia, Pa.

The content includes of his plans to have his son Richard, who lived with him in Turkey, go to New York and set up a business there, and then return to Turkey; Tells of his marriage in 1819 to a woman of Smyrna, Helena Courtovich, who was from one of the richest families there, but the family fortune was lost in trade, and he also tells of the birth of a son, also is his description of how his business is doing, and of the expected arrival of Commodore Bainbridge on the “Columbus” (William Bainbridge, 1774-1833, U.S. Naval Hero, his last service afloat was aboard the “Columbus” in 1820), and noting that, since he is the only American in Smyrna, he will be obliged to offer “every politeness & attention to my countryman”, but wishes that instead of the Commodore, a dozen American merchant ships were on their way, noting that he is expecting 5 or 6 soon, and while he is writing this letter, he announces the arrival of a ship from Baltimore.

Includes:

“I have not given up the idea of some day paying you a visit with my wife. That cannot, however, be until I have a son capable of taking my place here...my establishment here is too valuable to be lightly abandoned. It is in contemplation to establish Ricard & Issaverdery in New York. It is quite probable they will leave here early next Spring, and Richard, after some time, to return. I shall be proud to send Richard among my friends, for although he is my son, I must say he is a most amiable young man. I have preferred delaying their departure in the hopes that commerce and commercial men will become more certain ere long. Richard, also is rather young, but still, in his judgement, steadiness & perfect morality, I have the highest confidence.

I wrote you particularly about my Helena. I am rather doubtful whether you have received the letter. I have told you she is of one of the most respectable families in this place, and at one time among the richest. Before her parents death, which was within a few days of each other, the greatest part of their fortune was lost in trade. She has been brought up by a Brother & Sister, & while she has had the advantage of a good standing in Society, at the same time has been taught the value of money. She is silent, rather timid, patient, of great sensibility, little of which is shown in words, but in her actions; in person, tall, slender, a pleasing countenance, and on the whole, what is called rather an elegant than pretty woman. As the honeymoon is long since past, I think this must be allowed a favorable description of a wife.

I requested you, after leaving a melancholy blank in the family Bible, to register our marriage - ‘David, son of Daniel Offley, was married at Smyrna, in Asia Minor, 4th May 1819 to Helena Courtovich, native of that City’. I have now further to request you will add - ‘Henry Daniel Offley, son of David & Helena Offley, was born at Smyrna, 26th March 1820’, & thus at once I annouce to you the birth of my son, as fine looking boy as you would wish to see...

I am happy in being able to tell my sister that notwithstanding the very bad times, we have been able to keep clear of losses, except for some small amounts, which altogether may amount to five or six thousand dollars. We have little to do at this time, but last fall & winter our business was rather better than usual. With a good capital and a credit not surpassed by anyone in this place, we are enabled to offer good facilities to our friends, which will assist us to keep a good share of business.

We are told that Com. Bainbridge is expected here, with his Lady, in the Columbus. As I am the only American here, I shall have to depart from my retired system in that case, to offer every politeness & attention to my countryman. I will confess I had rather a dozen Merchant ships was on their way. Not so Master David [another of his sons] in particularly, who is on the constant lookout for her.

Well, since writing the foregoing, we have at least one rich merchant vessel to our address, from Baltimore, and reason shortly to expect two others. It appears we are never more to have any vessels direct from Philadelphia; in fact, so many of our friends have failed, that we are almost strangers among the present class of merchants...”

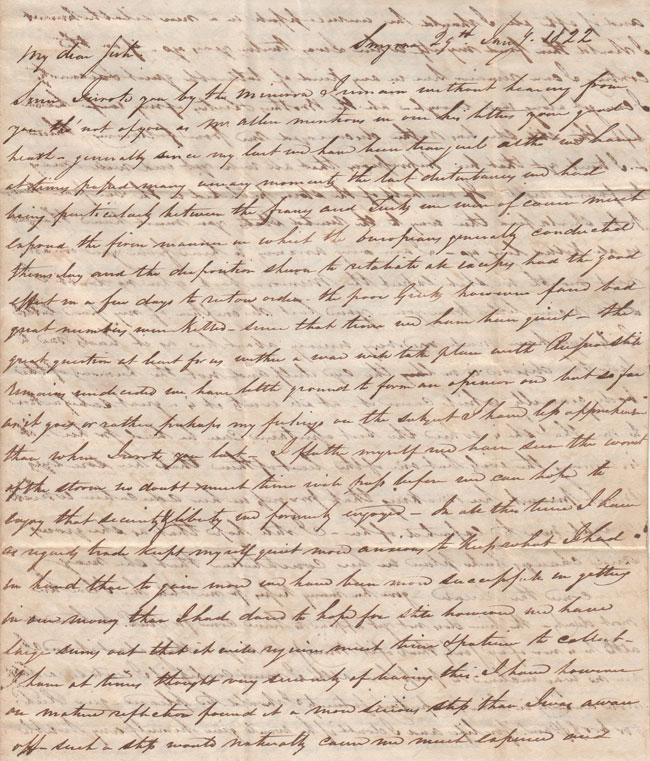

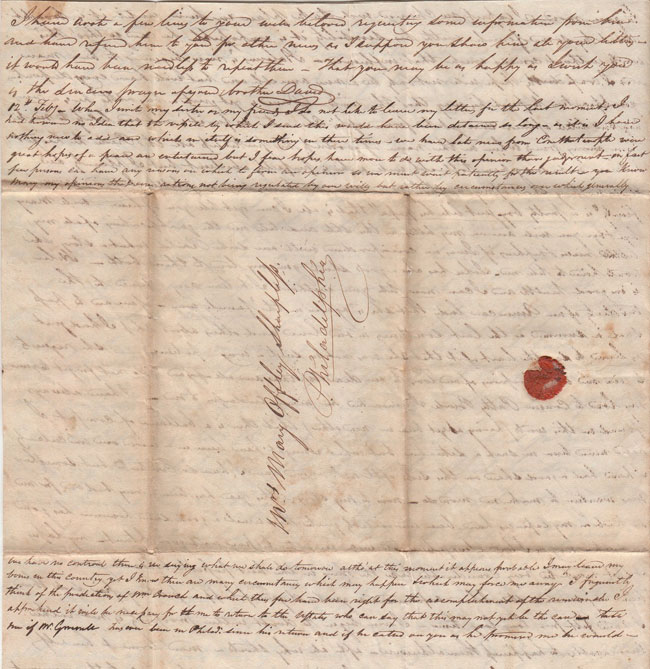

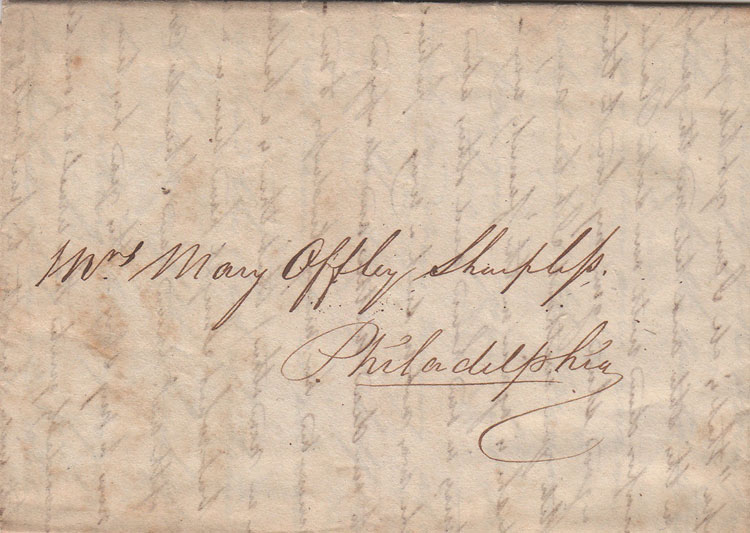

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, 18 February 1821, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs Mary Offley Sharpless, No. 178 South Front Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA.

Offley writes of his three sons — Richard Jones Offley (1800-1842), John Holmes Offley (1802-1845), & David Washington Offley (1805-1846) — who live with him in Turkey, and especially of his concerns and plans for the 20 year-old Richard, his oldest, who has been in Constantinople for a while. We learn from this letter that Offley’s daughter, Anne Powell Offley (1811-1839), was residing in Philadelphia with his sister, Mary (Offley) Sharpless, the recently married wife of Blakey Sharpless, to whom he wrote this letter. Offley’s first wife, and the mother of all these children, was Mary Ann Greer. After her death, Offley married a woman from Dalmatia named Elena (“Helen”) Curtovitch and had at least eight more children. Offley writes his sister that he has heard of a shoemaker in Philadelphia who cobbles shoes together with iron and brass, rather than sewing them, and sends his sister his measurements, asking her to have this shoe maker make him a dozen pairs, expecting that they will last him the rest of his life.

Includes:

Smyrna 18 February 1821

My dear sister,

The letter from our Cousin, Martha Reeve, 19th Oct., announced to me formally the marriage of my dear sister. I know of no language capable of expressing my pleasure and wishes on this event. I leave to your heart to understand the sentiments of mine. I beg you to repeat to my new Brother the welcome into our family, and my sincere wishes towards the accomplishment of all his desires. I further entreat his kind friendship to my little daughter, who I am much persuaded will profit by his addition to our family. My dear Helen [his second wife, a Greek Turk who he married in 1819] joins me sincerely in all my wishes on the occasion of your marriage. She is in good health, and expects every day to lay in.

Richard has been absent these three months past at Constantinople. I expect his return every day. I have been much flattered by all I have heard of him during his stay in that place. It is probable he will proceed to America by the first good conveyance. I feel much anxiety on his account. He will, this year, come to his 21st year, and I think it now time he should begin to walk alone. On the other hand, trade is so miserably bad that I cannot but reasonably fear that any capital I might be disposed to advance him will be quickly lost. I have many plans for him – an establishment at Constantinople – that he should go to the U. States, purchase a small vessel, & trade between this & Philad. – that he should pay a visit to the U. States without engaging in business, make friends & acquaintances, and thus pass two years. This would cost at least 2000 Dollars, and perhaps it will be less, then should he enter into business; and lastly and perhaps the best, that he should remain quiet where he is, until something might turn up.

As to Master Holmes [another son, who joined him in Turkey], you need not give yourself any uneasiness. He is in a good counting house, where I have good accounts of him. He is a great hand among the young ladies, and if I would only allow him as much money as he wants, would no doubt be better contented. This I believe is his only chagrin.

Master David is very domestic, grows finely, and when he shall be corrected of his insufferable pride, will make, I hope, a clever fellow.

You have never told me whether you rec’d from a Mr. Cabot of Boston, I believe 2, certainly one, cask of wine. A Capt. Chandler of Baltimore was to remit some money to Mother on Richard’s account. He has also in the hands of a house in N.York, 800 Dollars, which I shall advise him to deposit with the same Banker. These moneys are to be held to his order. The opportunity by which I now write, is expected to return here immediately; perhaps may not remain in N.York more than 20 days. Mr. Turnbull has promised me to let you know in time. I understand a Mr. Bedford, shoemaker in Philadelphia, is famous for making shoes nailed with Iron & Brass, instead of sewing. I enclose a measure, and directions for 1 doz. pair shoes, which I expect will last me the rest of my life, and which please order to be made. Pay for the same, and have them forwarded to N.York, care of Mr. Turnbull.

I have just heard of the arrival of Richard in the neighbourhood, where he is detained by a gale of contrary wind. I almost doubt whether he will arrive in time to write you. Remember me affectionately to Rachel and her husband…

Our poor brother John, I am anxious to hear how he comes on. He has gone so far, he must now go to the bottom of the hill, and if he cannot settle with his creditors any other way, he must go to prison, and then they perhaps will be more tolerable. Let him give up every thing he has, and then if his creditors will not give him a discharge, I hope his friends will do all in their power to assist him to get over by Law…

To my dear daughter, many kisses. Tell her to love her father, who never lets one day pass without thinking of her. When her eyes shall be well, then she will be more attentive to school and will be soon able to write her a letter. But should her eyes be so tender that such use of them would be injurious, it is much better she should entirely abandon school than injure her eyes; besides, for the best part of education, the eyes are no way necessary, or at least not absolutely so…

I remain most affectionately my ever dear little sister Mary, your affectionate brother, — David

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, May 25, 1821, (and continued on May 30th, and June 1st), from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

He writes that there is an Embargo in place on ships leaving Smyrna, so he’s not sure how he will get this letter out, and continues with a lengthy discussion of the outbreak of violence by the Turks against Greeks, and other foreigners in Smyrna, arising out of the war between Turkey & Greece. He notes that over 40 murders had been committed by the mob, and many Europeans, Americans, etc. had taken refuge on board ships. He notes that although there are 2 American ships in port, he was not invited to take refuge on either of them, and he made arrangements to go on board a Russian ship if it became necessary. He describes how the situation of his house is ideal for defense against the mob, and how the situation has caused business to come to a standstill. He notes that some calm has been restored in Smyrna, due to the arrival of a Pasha who has instilled some order there. He also discusses the perilous situation of Greece, and thinks they are lost unless some European power comes to their aid.

Includes:

“This moment that I sit down to write, a new embargo exists, but every thing is so uncertain, that perhaps it may be as quickly taken off and the Vessel by which I now write will depart that moment, so I must have my letter ready at the time. I wrote you the P.S. to my last letter...we were in the state of the greatest possible alarm and I was now believe with still more reason than even then knew of the Turks are, and with reason, exceedingly exasperated against the Greeks. Unfortunately, the strangers in town do not know how to discriminate between them and other Christians...The Governor and other authorities of the City had lost all command and respect among the lower orders, so that we were entirely at the mercy of an armed mob, and I look on it as really astonishing that in all that time, not more than about 40 murders were committed, and those principally where old quarrels existed. Mr. Woodmass had all his family on ship board, as had most other Europeans in the place. For my part, altho’ I had all preparations made to embark, I did not do it, having two children at the breast. To be on board ship was particularly agreeable. Altho’ we had two American vessels in the port, I had no invitation from either of them to take refuge on board their vessels until after I had engaged the cabin of a Russian ship on more occasions than one. I have had to remark that Americans in general have less nationality than any other nation.

Business is for the moment at a complete stand. Thank fortune we owe no money, and are unfortunate in having large sums due to us that God only knows how much of it we shall ever get. Our consolation is that with cash in hand, goods in store, and debts that we took on as perfectly secure, we always have a handsome capital left to continue business. The only difference will be that I shall not be able to render that assistance to my boys as they come of age, that I expected to do. I must now look out for my young children to secure them the advantages (if they are such) of a good education.

My wife has kept up her courage in a most astonishing manner (he married a Greek woman in Smyrna, Helena Curtovich, in 1820 - and as a Greek, she would have been in especial danger during the mob attacks). My house, it is true, is so situated on the marine that it is easily defended, and from which I have at all times a secure retreat on ship board.

Most fortunately for us, a Pasha has arrived & taken the command of the City and he has given us the assurance of perfect tranquility, and from what we have witnessed these three days past, we have reason to confide in his assurances. No disturbances whatever have taken place...the strangers are all sent out of the town, and our streets are no longer filled with idle Turks walking about in search of adventures. The Pasha is known to be frequently in the streets under different disguises, and as a wink from him is sufficient order to take off a head, every one is careful how he conducts himself. Yesterday I went thro’ all the Bajars and met with no insult whatever. It is where I would not have gone ten days ago for any consideration. All is tranquil at Constantinople....

30th May. All has been quiet, and we begin to recover our hopes that all may yet go well, except indeed for the Greeks, who are doomed certainly to suffere much. Business has a little revived, and we have been able to get in some money. We have some hopes the embargo will be taken off tomorrow morning.

June 1st. The embargo is partially taken off. A few vessels will be allowed to depart, and among the number, the American. We are tranquil and hope may remain so.

The accounts respecting the Greeks in Europe are very contradictory. This, however, appears most likely, that unless they are assisted by some European power, they will not be able to contend against the Turks. We hope here there is no danger of a war with Russia should their hopes be well founded. I trust the time is not far distant when every thing will be returned to its usual order. If otherwise, God only knows what may become of us.

I have not time by this opportunity to write Mr. Allen and if I had not began yours, it would have been the same. Please send for him and communicate to him the news of our situation. In trade there is nothing doing. I expect our produce this year will be very low....”

Kiss my dear little daughter for me. My love to mother, brothers & sisters in all which I am joined by my Helen as well as in the assurances, my dear sister, of our wishes for your happiness.

Your affectionate brother, -- David

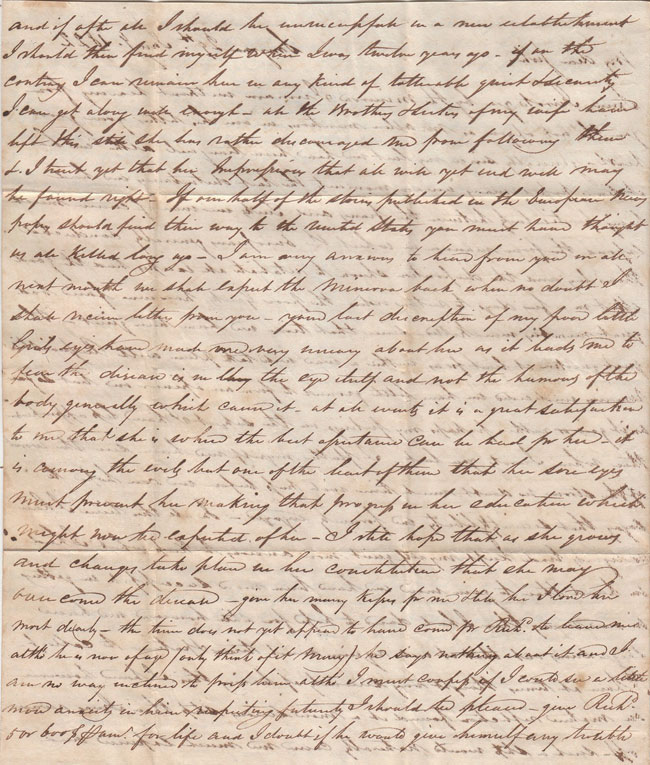

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, January 29, 1822, (and continued on Feb. 12th, as the ship he hoped to send the letter on, was detained) from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter was privately carried by ship to the U.S., and has no postmarks.

He writes of the attacks on foreigners in Smyrna by Turks (this violence was sparked by the Greek uprising, a war which lasted until 1829, culminating in the establishment of the modern Kingdom of Greece), and how the Europeans actions of retaliation helped restore order, but that the Greeks fared quite badly, with many killed. All of his wife’s family fled Smyrna (they were Greek), but she persuaded him to remain in the City. He also discusses fears of a possible war with Russia. There is also great content concerning how his business has suffered because of the trouble, and also much concerning his 3 sons, Richard, Holmes & David, who came to live with him in Turkey, and his expectations for their success in the world. Much more.

Includes:

“Since I wrote by the Minerva, I remain without hearing from you, tho’ not of you, as Mr. Allen mentions in one of his letters your good health.

Generally since my last, we have been tranquil, altho’ we have at times passed many uneasy moments. The last disturbances we had being particularly between the Francs and Turks. We were, of course, much exposed. The firm manner in which the Europeans generally conducted themselves, and the disposition shown to retaliate all excesses, had the good effect in a few days to restore order. The poor Greeks, however, fared bad. Great numbers were killed. Since that time, we have been quiet. The great question, at least for us, whether a war will take place with Russia, still remains undecided. We have little ground to form an opinion, and but so far as it goes, or rather perhaps my feelings on the subject, I have less apprehension than when I wrote you last. I flatter myself we have seen the worst of the storm. No doubt much time will pass before we can hope to enjoy that security & liberty we formerly enjoyed.

In all this time, I have as regards trade, kept myself quiet, more anxious to keep what I had in hand than to gain more, and have been more successful in getting in our money than I had dared to hope for. Still, however, we have large sums out that it will require much time & patience to collect. I have at times thought very seriously of leaving this. I have, however, on mature reflection, found it a more serious step than I was aware of. Such a step would naturally cause me much expense, and if after all I should be unsuccessful in a new establishment, I should then find myself where I was twelve years ago. If on the contrary, I can remain here in any kind of tolerable quiet & security, I can get along well enough. All the Brothers & Sisters of my wife have left this, still she has rather discouraged me from following them, & I trust yet that her impression that all will yet end well may be found right. If one half of the stories published in the European newspapers should find their way to the United States, you must have thought us all killed long ago...

Your last description of my poor little girl’s eyes [his daughter Anne, who he left in the care of his mother & sister when he left for Turkey] has made me very uneasy about her, as it leads me to fear the disease is in the eye itself and not the humours of the body generally which cause it. At all events, it is a great satisfaction to me that she is where the best assistance can be had for her. It is among the evils, but one of the least of them, that her sore eyes must prevent her making that progress in her education which might now be expected of her. I still hope that as she grows, and changes take place in her constitution, that she may overcome the disease. Give her many kisses for me, & tell her I love her most dearly.

The time does not yet appear to have come for Richard [his son, who lives with him in Turkey] to leave me, altho’ he is now of age (only think of it, Mary). He says nothing about it, and I am no way inclined to press him, altho’ I must confess if I could see a little more anxiety in him respecting futurity, I should be pleased. Give Richard 5 or $600 per annum for life, and I doubt if he would give himself any trouble to gain more. I expect no change will take place in him until it is brought about by some female. With his sensibility, it is impossible he can go thro’ this world without coming under that influence.

Holmes [another son living with him] is now beginning to be a man, and I confidently hope will not only be a very amicable one, but will have every disposition & qualification to push his way thro’ this world. David [another son living with him] is yet quite a boy, altho' he is a very big one, little opinion can yet be formed of his character. So far it is not one likely to make him many friends. Where in the name of goodness he picked up all the pride he has got, I know not. We get on tolerably well, as he is perfectly obedient, but I plainly see that nothing short of my authority would make him so.

My little Edward [a son born to him from his second marriage, to a Greek woman in Smyrna] grows finely, & ‘is a pretty boy, just like his father’. That is all I can yet tell you of him....Helen [his Greek wife, married in Smyrna in 1820] is in good health, and I can now tell you, without, I believe, any offence to the modesty of an American lady, that she is again in the ‘family way’. If we are to pass such a summer as the last, sometimes in our house, and others aboard ship, I had just as leave today, to say the least of it, that she was not in such a way...

This year has been a very bad one for me in trade, as my expenses have been unavoidably greater than usual. A good sum, however, has gone in such a way as I have always been told will hereafter be paid with good interest. My losses at last must be very considerable. Take the thing in the best possible light, the gains have been very small. Still, I have experienced a greater degree of happiness at my fire side than I have felt for a long time. I even being to doubt whether prosperity is not rather inimacable to happiness than otherwise. After all, why should a man torment himself about tomorrow who is to die this night. My means are still equal to the acquirement of all things necessary or useful to me. My children will not have the opportunity of spending as much money as they might have had under a different state of affairs, & certainly there is no harm in that. So then, all things considered - patience...

12th Feb’y. When I write my Sister or my friends, I do not like to leave my letters for the last moment. I had, however, no idea that the vessel by which I send this would have been detained so long. As it is, I have nothing new to add, and which in itself is something in these times. We have late news from Constantinople, where great hopes of a peace are entertained, but I fear hopes have more to do with this opinion than judgement. In fact, few persons can have any reason on which to form an opinion, so we must wait patiently for the result. You know, Mary, my opinions that our actions, not being regulated by our wills, but rather by circumstances over which generally we have no control. There is no saying what we shall do tomorrow, altho’ at this moment it appears probable I may leave my bones in this country, yet I know there are many circumstances which may happen & which may force me away. I frequently think of the predictions of Mr. Crouch, and which thus far have been right. For the accomplishment of the remainder, I apprehend it will be necesssary for me to return to the U. States. Who can say that this may not yet be the case...”

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, April 21, 1823, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter has red “BALTIMORE MD.” cds, red “SHIP" handstamp, and manuscript “14-1/2” rate. The Baltimore postmark is dated July 22nd, indicating that the letter took 3 months to reach the U.S.

The letter includes writing about his son Richard, who has gone to the U.S. on a trading venture, with $2000 given by his father, to make his way in the world, and his plans to do this for each of his sons, noting that this is a one time only monetary assistance to them. He also expresses a hope that peace will be restored in Turkey (the Greek rebellion was raging at this time). More interesrting content, including writing that his 2nd wife (a Greek woman, Helena Curtovich, who he married in Smyrna in 1820), has “become more reasonable” since the first years of their marriage, and is presently nursing their 9 month old child, Edward. He also playfully teases his sister for not writing as often since she has married (she married Blakey Sharpless in 1820).

Includes:

“Somehow or other since your marriage, I have received very few letters from you. I must, however, my dear Sister, be just, and allow that ladies who have a child...and pay the attention to them that I am sure you do to yours, have not so much time to spend in letter writing. Not that it takes so long a time to write a letter, but when one is out of the habit of so doing, it requires some exertion to sit down to it; and then, when you feel half disposed, the child cries, or some other such accident, and it is put off for another time... I do not therefore believe that however the cares of a family may deprive me of receiving letters, that she loves me any jot the less for all that. So this matter is settled, and as friends say, my mind feels the easier for it.

As you are now a married lady, I can talk more plainly to you about family matters. My dear Helen, who joins me in love to you and all our friends, has become more reasonable than she was in the first years of our marriage. Our little Edward is now nine months old, and I am certain of not having another child at least before another nine months. The child she nurses, and finds her health all the better for it.

A vessel has just arrived from Baltimore, where I hear Richard was [his son, Richard J. Offley], and although I did not receive a letter from him, I am satisfied it was not his fault. I suspect he could only have remained with you a very short time, and that it would not be long before he returned. I beg my dear sister, you will have a kind & friendly eye over him. Perhaps a word from you may at times be necessary, and do more than sermon. He left me a good young man, who I believe never told a falsehood in his life, his morality unimpaired. God send he may ever remain so. Advise him about expenses. He must now think for himself. I gave him 2000 Dollars to ply in the world with. My family & my fortune will not permit me to renew this gift, and he must now think as much of gaining as spending money. Holmes [another son] will probably land here this winter, to whom I shall give a like sum, and until I have so done by all my children, & find myself and wife provided for, it is not likely I shall renew it.

We are all peaceable and quiet here. God grant it may long remain, for I really fear I am chained to this spot for the rest of my life. I cannot account for it, but so it is, & I shall not be surprised if by the receipt of this, Richard should be wishing himself again in Smyrna...

A thousand kisses to my dear little girl [his daughter Anna, who he left in the care of his mother & sister in Philadelphia when he came to Smyrna]. If Peace should once more be an inhabitant of our Country, and Richard or his Brothers should return here, particularly with an American wife, then I shall wish to see my dear child...”

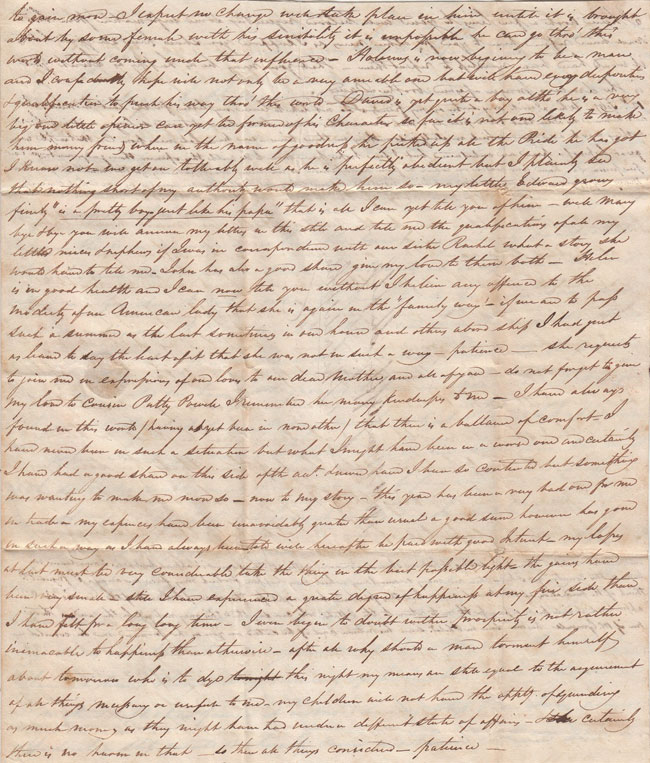

Below is another, 3 pgs letter, dated Smyrna, Turkey, August 11, 1823, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter was privately carried by ship to the U.S., by his son John Holmes Offley,(as mentioned in the letter), and has no postmarks. There is a red wax seal on the back, with a Turkish inscription impressed in it (see the last photo).

He writes of his son John (John Holmes Offley, 1802-1845), who had come as a youth to live with him in Turkey, and who is sailing with this letter to the U.S., where, with $2000 given to him by his father, he is to make his start in business. He also writes of his son Richard, who he had also sent to the U.S. with the same gift of money. Of special interest is his reference to the Greek rebellion, and how the war between Turkey and the Greeks has caused him to lose a considerable amount of money.

Includes:

“My dear Sister. You will, I expect, be rather surprised at having this letter handed you by John. His great desire to visit you has induced me in this instance to act rather against my judgement in permitting his departure. He will not be of age until October next, and I had rather he should have delayed his departure two years after than to have gone two months before. I have, however, suffered his desires to prevail once more. God knows how anxious I feel for him. He is a good young man, but not so steady as his Brother, and he will, I fear, need much more of your good advice. He is very fond of company, in the choice of which I have however no doubt he will be careful. I have endeavoured to impress on his mind what a serious task he has undertaken. He now leaves a father’s house and care to take on himself the direction of his conduct thro’ life. I have given him in money & goods, a like sum with Richard, say, two thousand dollars, and which is all he is to expect of me during my life time. What more he may sometime have to receive depends on thousands of circumstances over which neither him nor myself have any control. If Richard and him can do no better, I recommend them to use their exertions to make friends who may ship a cargo by them to this place, and return her to establish themselves, in which case my experience would still be useful to them, and when under my direction, I should be able to make them such further loans of money as might be necesssary to carry on their business without endangering the competency I now have, and which no consideration shall induce me to do.

My losses by the Greek rebellion have been considerable. I have, however, just enough left to insure me a sufficient competency according to the economical manner I now life in these times. At my age, & with a young family round me, my sense of justice & propriety will always make me adhere to this determination, and which when you see an opportunity & necessity, you will please inform to my sons as a spur to their industry & exertions.

It is a long time since I heard from Richard. He has never wrote me one letter by post since he left me. From you I have not a single line since his arrival in America, & I must confess I anticipated much pleasure from the opinions you would give me of Richard. I feel great anxiety for my sons. The reflection that they will get along about as well as other young men is my greatest consolation. It appears to us here that Richard has not pursued his plan of connecting himself with his Boston friend with sufficient zeal. We may not, however, be well informed.

After two years, David [another son who came to live with him in Turkey] will want to start out. He is a little giant, three inches taller than I am, and every day growing. His character is not formed, it is different from the others...it will be some years before you will see any of my new race [a reference to two infant sons born in Smyrna to his second wife, a Greek woman who he married in Smyrna in 1820], altho’ it is my intention, should my circumstances permit, to send them to America to finish their education. They are two fine children, and as yet there is no appearance of a further increase of family. If it comes - come in welcome - if not, I shall not be sorry. My dear little girl, [a daughter he left back in the U.S.] some day will want to come and see me, and as she will have Brothers passing & repassing the ocean, I shall wish her to come. Give her many kisses for me and tell her to love me...

I should like once more to pay you a visit before I leave this world. Perhaps circumstances of which I now have little idea, may cause me to gratify this, and sooner than I expect.

Richard appears highly pleased with ‘friends’ [Quakers - the Offley family, except for David, were pious Quakers], and says according to his ideas, they are decidedly the most polite people he has met with. In this I join him. Their education certainly tends more to make people happy in this world than any other sect, but one which I dare not mention [the one he dares not mention is Islam, of which he was very impressed, as noted in another letter of his].

Well Mary, bye & bye you will have children roving about the world, and then you will know what the heartache is. You now only know what the arm ache is...[he means the arm ache of holding babies]...”

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, October 14, 1824, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter has red “NEW-YORK” cds, red “SHIP” handstamp, and manuscript “14-1/2” rate. The NYC postmark is dated Feb. 26th, indicating that the letter took nearly 4-1/2 months reach the U.S.

The content concerns the atrocities committed by the Turks in capturing the Aegean Island of Ispara (now called Psara), killing many inhabitants, and enslaving many of the Greek Christian women and children. He writes how he bought the freedom (ransomed) of a 12 year old Greek girl, who had been tortured in an attempt by her Turkish master to force her to convert to Islam, and she is now living with him. Much more great content on this subject, and his hopes that Quakers in Philadelphia may contribute money for the ransoming of these Christian slaves. He also writes of the war between the Turks and the Greeks, of how naval battles often take place in view of Smyrna, and how the Greeks in Smyrna are better treated than previously.

Includes:

“You will have learnt that some time ago, the Turks took and destroyed the Island of Ipsara. Fortunately many of the inhabitants escaped. Many however, were killed, and numbers of women & children made slaves, and brought to this place. It is not easy for me, my dear Sister, to tell you how much I have suffered on these peoples’ account. I have seen Mothers torn from their children, and one of them from each other, to be sent to different quarters of this vast empire. Some few have been liberated. The inhabitants of this City have done much, but so great is the evil, that it is like the drop in the ocean. I can tell my sister that I have done my share fully, and often my heart leads me far beyond where my reason will follow.

The example of a poor woman in my neighbourhood has had much effect on me. She has sold all little superflueties and many necessaries, which with her time, she has devoted to the most Christian of all Christian acts - rescuing children and women from the hands of the Turks. I have now sitting by my side a dear little Ipsariater girl of about 12 years. This child was in the hands of a particularly ferocious and bad Turk. He had her tied up and beaten to force her to renounce her religion, for which she only replied she was ready to die. Her beauty notwithstanding, her tender age had exposed her to every insult from this barbarian. When I saw her, she gave me a look that I never shall forget. It was full of hope and despair. Her owner demanded a large sum for her. With some management, I got her for 320 dollars. I am not yet certain whether her father lives, but she shall never know the want of him so long as I do. Her mother is a slave, but I know not where.

The usual manner of liberating slaves is by subscription, at which I have done my part with great regret that prudence, the worst and best of virtues, would not permit me to do more. How often have I wished I could bring to the mind’s eye of the best of people, the friends of my father, [his father was a Quaker minister], and who I am ready to acknowledge I am hardly worthy to call mine, the misery I am so often obliged to witness. I am certain... the friends of Philadelphia would readily afford their help to restore children to their parents, and rescue Christians from Mohametans. A warm hearted countryman of mine, whose warm and youthful feelings I am sometimes obliged to... after we had each expended in this work of charity, more than prudence would justify, proposed we should advance 2000 Sp. dollars, and purchase the amount of slaves for account of the friends of Philadelphia, and his heart, he said, told him our agency would not be denied, but that double the money would be sent me, and that if we were disappointed, to divide the loss between us. At his age, I should have agreed to this proposal. I do, however, believe with some influential friends to undertake the business, a sum might be collected that would be the means of relieving misery, and making glad the hearts of many. In my lifetime, I have spent much money in pleasure, but did mankind know & feel how much pleasure there was in doing good, how much of it there would be done. When I get to be a Quaker preacher, this should be my task.

I am much in hopes that this winter some arrangement will be made between the Turks and Greeks. The latter in this place are now well treated, and it is many months that no instance of assassination has occurred. We flatter ourselves with the hopes that all danger of witnessing past scenes again in this place will not occur. It is really astonishing to see the confidence that exists. All Europeans at this Country knows the roads & streets full of Greeks, and that which the Turkish & Greek fleets these days past have been fighting almost within sight of us...

You will of course read this letter to your Husband. May he be tempted to try if anything is to be done for the poor Christian slaves...”

Below, letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, July 29, 1824, from John Holmes Offley, to his Aunt, Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa. John Holmes Offley (1802-1845), was born in Virginia, and died in Georgetown, D.C. As a youth, he came to Turkey to live with his Father, David Offley (1779-1838).

He writes that he tried to persuade his father to visit the U.S., but his father feels that he is too old to make the voyage, and as for residing once more in the U.S., feels that he has been too long in Turkey and its customs, to be able to live in America again. Much more interesting content.

Includes:

“My Dear Aunt, You will no doubt be accusing me either of negligence or something worse, but I flatter myself that, when you hear that I am alone here, to do all the business of a commercial house not being yet able to afford a Clerk, you will hold me excusable. Richard [his brother, who also lived with their father in Turkey, and was at this time on a visit to the U.S.], however, will, I hope, not have neglected my different messages to you & Uncle B. [Blakey Sharpless, husband of his Aunt Mary]. Richard will no doubt have informed you of all the circumstances of my voyage... Here I am enjoying good health.

If you remember, I promised to do all in my power to engage Father to pay you a visit. Well, I have used all my best arguments, but in vain. He appears to have given up all idea of ever seeing his Dear Country; not that he does not wish to, but he begins to think himself too old to make such a voyage, and as for going there to remain, he thinks it impossible, having resided here so long, where manners, customs, & every thing is so different from those of America. He thinks it would require too long a time to accustom himself to life in America. He will no doubt have told you all this, so I will leave the subject to talk of other matters.

Since my arrival here, I have had but two letters from Richard. I cannot imagine what he is about. Has he forgotten he has a house here?, and how absolutely necessary it is for me to be well informed on the course of Trade in the United States? I entreated him to write me at least once a month. He promised he would. I have written him at least 14 or 15 long letters since I have been here, and have so exhausted the different subjects, that I am quite at a loss what to say. I wish you would stir him up a little. He is not cut out for a Merchant, I am afraid. Father is so vexed with him that he is determined not to write him anymore, nor has he done so for a long time. He also complains much of all his friends. Ah! if they would but consider but one moment our situation here, I am sure they would let us hear from them, were it but for pity’s sake. Our neighbours are receiving letters every day almost, & it is from them we get what information they are well pleased to give us. I have, however, exposed my reasonings on this subject so very plainly to Richard, that I feel pretty confident he will be more regular hereafter.

I have been pretty fortunate in my commencement in business, and hope to give such satisfaction to our friends, as will encourage them to keep up the business. But where shall we be, if we lose what few we have, and Richard does not stir himself to increase the number. I am afraid he does not think at all about business. Do stir him up. Perhaps an Aunt’s, and a dear Aunt’s advice would have a better effect than that of a Father or Brother.

Since I have left you, I have very often thought on what I told you one morning as I was going to Fancy Hill. Do you remember you said you began to suspect there was something very attractive there, and I told you no - for I was engaged in Smyrna, and you would believe it, altho’ I contradicted it afterwards myself. Let me now assure you that I am perfectly free from the snares (that is the word) of our Oriental dames. Before I visited the U.S., I had a different opinion from the one I now have. But now I see they can bear no comparison with our dear, dear Countrywomen. Ah! how differerent. Our fair ladies of Turkey, for the most part, have only pretentions without reality; are mere shadows without substance. I must however confess there are some very pretty, but what is beauty without the other qualities so necessary to make a man happy in the matrimonial life. When that is gone, there you are buried alive, with a lump of clay. Ah! give me the Yankee Girls - who join to beauty; talents, grace, good manners, and love. Here, they can easily talk of love, but I think they never feel it. Excuse me, my dear Aunt, for you know this is my favorite subject. Perhaps you might think it more adapted for the ear of an unmarried lady. I wonder if Richard ever got in love; he always told me it was great foolishness. How little he knows about it.

At home, we are all well. Mother would like much to pay you a visit. [“Mother” is not his birth mother, Mary Ann Greer, who his father divorced, but his father’s second wife, Helena Curtevich, a Greek woman he married in Smyrna in 1820]. Ah! I wish you knew her. She is perhaps the only one in Smyrna that could have made Father so happy as he is. Little Edward [a child born to his father & his 2nd wife] is a beautiful little fellow. Henry [another son of the 2nd marriage] is one of the stout, independent, sober kind of boys - cares very little for anybody. Eliza [a baby daughter born to them that year] will be handsome I expect. Our big Brother David, [his real brother, who also came to Turkey to live with their father - he is really a younger brother, the term “big” refers to his size for his age] is very well, & you may easily imagine how many questions he has to make me. He wants very much to pay you a visit. He talks of Cousin Anny Dawson a good deal. He is an immense man - taller than Father - very quiet by the bye, but that is rather through his independant character than any thing else...”

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, August 9, 1829, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter has red “NEW-YORK” cds, red “SHIP” handstamp, and manuscript “14-1/2” rate. The NYC postmark is dated Oct. 12th, indicating that the letter took a little over 2 months to reach the U.S.

The letter includes an account of how he feels he is prematurely aging at age 48; spent the past winter at Constantinople, and was often in knee deep snow there, which leads him to believe that spending a winter in Philadelphia would “finish” him; He writes of his 3 grown sons (from his first marriage), who live with him in Turkey, and of his small children (from his second marriage in 1820 to a Greek woman in Smyrna, Helena Curtovich), and asks his sister to make an addition to the family Bible, by noting the recent birth of a daughter in Smyrna. He also writes of how they pass the summer months in Smyrna, but plan soon to go to their home in a village 7 miles outside the city (Burnabat). Of special interest is his comments on how the Greek Revolution has made serious “inroads” on his finances (the war between Turkey & Greece ended the year this letter was written, and the modern Kingdom of Greece was established), and his hopes that restoration of peace will increase their business opportunities, and also he voices complaints of how the U.S. Government owes him money for services rendered and money advanced, and that he feels the U.S. Government “use me very ill in delaying the payment”.

Includes:

“It is a very long time since I had the pleasure to receive a letter from you, and the state of your health when last you wrote, has made me very anxious to hear from you. I am aware that you seldom can hear of opportunities, as the commerce between this place and the U. States is nearly all carried out from Boston, and which I am persuaded is the reason I so seldom hear from you. The duties of a mother occupy much time, but for one who has so great a facility in writing as you have, that cannot occasoin your silence, and I am less willing than all to believe our long separation can have occasioned any dimunition in the brotherly affection I know you have for me. I think much and often of you, and dear Mother’s image is as perfect in my imagination as if it was only yesterday I saw her...

Here we go on as usual. To begin the account with myself, I must tell you I feel most sensibly the approaches of old age, and have many tokens to warn me that I am likely, as respects health, to be a tolerably miserable old man. I suffer at this moment much with the rheumatism in my knees. I am nearly bald, my teeth are fast decaying, and without spectacles I cannot even read a newspaper. Yet, I am only 48 years old. Perhaps my travels, change of climate, &c. may have occasioned a premature old age.

The past winter I spent in Constantinople, where frequently the snow was knee deep. I was not for one day in the enjoyment of good health, & I am well convinced that a winter in Philadelphia would make a finish of me. Contrary to your ideas (for every thing is different in this Country), we are in town to pass the summer heats. When they are over, I shall retire with my family to a neighboring village, distant about 7 miles, to pass the remainder of the year, where, what with gardening and little carpenter jobs, I pass my time pleasantly enough.

Richard & David [his sons] are with me and doing little or nothing, waiting for such changes as we hope peace may bring about, to engage in business. Holmes [another son], I believe is doing something in Trieste. My little ones are all in the enjoyment of fine health, and make in my house and under my eye, good progress in their education. I have another entry which I beg you to make in the family Bible - ‘1829. Catherine, daughter of David and Helen Offley, was born at Smyrna, in Asia Minor, on the 28th July’. My dear Helen is quite well and desires her love to you all. She is yet confined to her room, but hope in a few days she will be able to join us again at table.

Give my best respects to your Blakey [his sister’s husband, Blakey Sharpless]. Tell him I hope...to hear that my small draft on the Secretary of State has been paid. They certainly use me very ill in delaying the payment of my drafts for money advanced by me for the use of Goverment, without fee or reward for so doing. It is now a long time since I have been rendering services to our Govt. without any renumeration. I trust eventually from their Justice, that I shall receive some, and which will be most acceptable. Without business, and a very large family to support, it requires no little management to make both ends. Most this, but nothing more I have been able to do for some years past. The Greek revolution and S. Williams’ failure made a real inroad in my finances...”

Letter dated at Burnabat, Turkey, May 27, 1831, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter has red “NEW-YORK/SHIP” cds, and manuscript “27” rate. The NYC postmark is dated Sept. 1st, indicating that the letter took over 3 months to reach the U.S.

He writes being sceptical about reports he has seen in U.S. newspapers that the Government will compensate him for his services in Turkey (as U.S. Commercial Agent, and in negotiating the U.S.-Turkey commercial treaty). He also writes of his 3 sons from his first marriage (Richard, David & Holmes), who came to live with him in Turkey when they were young, one of whom is working in a Counting House in Constantinople, another has sailed on a commercial venture to the U.S., etc., and also ponders where in the U.S. to send his 2 young sons from his second marriage to a Greek woman in Turkey, so they can be educated. Some of his friends in the U.S. Navy have recommended Virginia, but he doesn’t want to send them to a boarding school, preferring that they go to a country school. He also writes of his daughter Ann, who he left to be raised by his mother in America when he went to Turkey, and his concerns over her going to parties, and how he thinks it is fortunate that her “young man” has sailed to Calcutta.

Includes:

My Dear Sister,

I have had the great satisfaction to receive your letter 23 February and to learn that you were in the enjoyment of good health. Before the receipt of this I trust you will have seen Richard [his son, Richard J. Offley, who lived with him Turkey] and I hope his councils to his sister may have a good effect. I disapproved very much of the parties [my daughter] Ann appears to make not infrequently into the country. Of course I do not allude to those to our relations or when accompanied by them. Before the departure of Richard, we frequently spoke together on this subject. He will communicate my wishes to her and which I repeat in the enclosed letter. Ann has had every advantage of good example and if she has not profited by it, I must suppose her hereditary disposition are more strong [a reference to Ann’s mother, his first wife who he divorced, and who he describes as a “monster” in another letter]. I think it is unfortunate both for the young man in question and Ann that he should have made the voyage to Calcutta. She has not said a word to me on the subject nor have I myself to her letter.

I have always feared the climate of Woodbury [New Jersey] was not good. As I find my recollections are correct, have abandoned the idea of ever sending them there [a reference to sending his young sons to the U.S. for their education]. If it had been otherwise and agreeable to our sister and her husband, I should have sent them this fall. Although young, I have that confidence in the character of Edward that I would not only trust him in a great measure to take care of himself but also of his brother who is to accompany him. My ideas on the subject of education has undergone a great change since last we were together and perhaps some day I may have a fair opportunity of judging by comparison if the change has been for the better. Having said this much, I must, however, in justice to my sons Richard & David add that I know not two more respectable and respected young men. their conduct on all occasions has been moral & correct. Of Holmes, I cannot in truth say so much. The difficulties he has had will be a lesson to himself and wife (for never was sister & brother more alike) which will be of future service to them.

David is in a Counting house at Constantinople. I hear frequently from him and trust he is in a fair way to get rid of some of his excessive pride and high ideas. As to my little ones, I feel undecided when or where I shall send them. Some of my Navy friends advise me to send them to Virginia and offer to take them. I cannot, however, decide so to do. I would rather have them boarded with some happy and good family in Country and to attend some Country school where they would be happy than to send them to any boarding school where as much pains are taken to excite their emulation, envy, or ambition — call it what you will — and which must tend to make them bad and unhappy...

Please present my best regards and thanks to your kind husband for his letter. The vessel by which the box was sent went first to Constantinople. The Captain says David took it out of the vessel as I had another box Garden sent & newspapers from New York. Perhaps he thought one was enough for me. I have wrote to him enquiring if it was so and have not yet received an answer. I shall by next opportunity write to my old friend S. Hagan to thank him for his kind attention. I trust to you my dear sister to make my thanks acceptable to your husband for his present of the Annals of Philadelphia. I have had a copy sent me some time past and I see the mention of our father although his name is not spelled right. I am anxious to see the account of J.S. Lewis. I think there will be something remaining in his hands to add to the sum. I am preparing for the education of my children in the U.S. I see a great deal said in the newspapers relative to a compensation to be made by our Gov. I much doubt having as little confidence as their generosity as justice within anything worthwhile will be offered for my acceptance.

Give my love to our dear Mother, Brothers & Sisters. My little family or rather family of little ones are in the enjoyment of high health & happiness. My dear Helen requests to join me in love to you all.

With sincere affection my dear sister, — your brother David

Below is another, 3 pgs letter, dated at Smyrna, Turkey, Dec. 15, 1831, from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter has red “NEW-YORK” cds, red “SHIP” handstamp, and manuscript rate. The NYC postmark is dated March (1832), indicating that the letter took about 3 months to reach the U.S.

Includes:

“Since I last wrote you, our City has been visited by one of the most dreadful diseases that I believe ever afflicted mankind. The Cholera Morbus raged here for about six weeks with great violence, particularly during the middle of that period, and notwithstanding a good proportion escaped death when timely assistance was given, the number of deaths during that short period exceed seven thousand. In the first part of the disease, it was not a very uncommon sight to witness on our streets of a person, apparently in good health, falling down instantly as if dead, the extremities cold as ice, and the countenance that of a person some hours after death. These cases, when immediate assistance was given, were generally saved. As the disease advanced, it assumed other appearances, and even to this day, we hear of occasional attacks. I retired with my family to the country, where the disease was not near so violent. By a strict attention to diet, and avoiding exposure to the night and morning air, no attacks occured in my family. The diet consisted in soup, boiled & roasted beef or fowls, avoiding all kinds of fruit, vegetables, fish, & milk in all its varieties; in fact, everything but soup & boiled or roasted meat. And I believe when strict attention has been paid to this diet, no attacks have taken place.

The first part of the year, we had the plague, and then the word was don’t touch that; afterwards the Cholera, and then, don’t eat that. Here you will say, then why, my brother, remain in a Country so afflicted? I must confess I cannot answer reasonably, either to you or myself. It appears as if we were spell tied to this Country. During the Greek Rebellion, many Europeans, in a fit of desperation, left here. They have all returned, one after the other... Our doings, and even our opinions are so acted on by previous circumstances beyond our control, that when the moment of action arrives, we are obliged, as it were, to act according to our different characters at that time, formed from the millions of circumstances which have happened to us thro’ life, and then to life itself. Circumstances which happened in my early boyhood, had they been otherwise, I should perhaps not entertain the opinion I now do, and certainly (almost) never been a resident in Smyrna. The death of our father is among the most prominent ones, and to those but acquainted with his opinions and force of character, would I look for a coincidenc with my opinion. Present appearances are (and much I regret it) that here I shall end my days. There are many circumstances, however, within the range of possibility, any one of which happening would cause me to leave here before night.

After a very long silence, I have at length received a letter from Richard [his son, Richard J. Offley, who came to live with him in Turkey around 1820], and I regret to find the ten years which have passed since his previous visit to the U. States, appears to have affected but little change in his character, at least so far as Commercial enterprize and Industry are concerned. His present visit appears likely to end without any advantage to him, and most serious disadvantage to me, and will oblige me to deprive myself and family of some of our accustomed expenses, and what I most regret, will entirely put it out of my power to send my two sons to the U.S. In place thereof, if a person qualified to give my children a plain English education could be found, who would be willing to come here for $200 per annum, board, lodging & washing, I should be glad to have such a one. There would remain for him a sufficiency of time, either by trading, in which I would assist him, or by giving lessons to other children, to add very considerably to his gains. I have wrote Richard several times on this subject. I should wish a person acquainted with teaching children, and if a friend [a Quaker - David Offley was the son of a Quaker minister, and his sister remained a devout Quaker], could reconcile to himself to mix with those who are not so, I should be pleased.

David [another son who came to Turkey to live with his Father] is back again. His intellectual pride will, I fear, prevent him from ever being a subordinate to anyone, & I see nothing in his character or abilities which affords much hope that he will ever be anything else. Holmes [another son who came to Turkey] appears to be, or certainly is, the only one of my children who secured for themselves a piece of bread since he has been forced to lay aside his pride and go to work in the best way he can; is doing well. He now maintains himself by his own exertions and industry... Richard has not wrote so to me, but I have heard that in July, he was jaunting about with his sister, spending my money instead of occupying his mind with business, at which I most highly disapprove of. My sons are gentlemen, moral, and with fair abilities, but they are as... unenterprising and idle as any I know of. They rely entirely on me. What will become of them after me, they ought at least to think of...

My family are all well. When next I write you, I expect to have to request you to make another entry in the family bible. I am very unfortunate in getting letters from the U.S. My friends I hear, say they write me, but their letters never come to hand...I endeavour not to let these disappointments distress me as they once did. Besides, perhaps it is only natural after so many years of absence, that I should be nearly forgotten. There is something so painful in this idea, that I frequently tell my wife that I shall be obliged to make at least six months visit to the United States to renew my acquaintances...”

Thesis on this person and the wider early US-Turkey relations: Yankee Levantine: David Offley and Ottoman-American relations in the early nineteeth century - Ayşegül Avcı, 2016