The Interviewees

Interview with Gillian Mueller & James de Wesselow, September 2024

1- You published in 2011 a family saga dealing with your husband’s side of multiple identity (ethnic German in WW2 ravaged Poland), their perilous existence in that environment and later escape to America via Austria, presumably based on their real history as much as you could piece together. Do you think this study of family history and retelling half-lost stories was a good grounding for your later work on the Baker family and business story of Constantinople that stretched from around 1854 to 1964 so covering around 4 generations?

Gillian Mueller: Collaborating with my Polish mother-in-law to write You Have No Idea was indeed good practice for the Baker project, but a much simpler process. There the task was to organize and edit her notes, memories, and papers. The Baker project is broader and more complicated, spanning several generations as you said — George Baker, his son Arthur Baker, and Arthur’s daughter Elsie (my grandmother). I started with the last: my American grandfather going out to Constantinople from Spencer Massachusetts in 1909 as one of the State Department’s first Student Interpreters, and his tumultuous courtship with Elsie Baker, based on their “secret” love letters, heading into World War I. Then I turned to her grandfather George Baker, the very reason she and the family were Levantines. But while I had a fair idea of the arc of his life, I knew nothing about late Ottoman history. I had to educate myself with help from John Freely and a small library of his and other books on Turkey. At the same time, I gathered whatever Baker memorabilia I could get my hands on—letters, journals, written accounts, official records, old family photo albums, etc.

Thereafter it was a matter of organizing the material into points of interest: George’s humble beginnings, his garden training and voyage out to Turkey, his transition into trade, his unusual relationships with Sir Stratford Canning, Sultan Abdul Mejid, and Robert College founder, Cyrus Hamlin, among others. I’ve tried to weave into these headings the dramatic events of his time (the decline and dissolution of the Ottoman Empire) and some description of his circumstances (Constantinople between 1848 and World War I). I’ve highlighted the historical undercurrents that pushed George in one direction or another; for example, Britain’s obsession with gardens and gardening just as George was coming of age, or Britain’s geo-political expansion eastward in her pursuit to secure trade routes to and dominion over the Middle East and India. One thread of George’s narrative was his desire to escape his shameful past and England by expatriating himself to Turkey.

I became interested in George Baker when my husband and I visited Istanbul in 1986 and anecdotes my father had told me as a child, when we lived in Turkey in the 1960s, percolated to the surface. They stirred my imagination and a desire to know more. Long before me, two of George’s sons, a granddaughter, and a great grandson had put some effort into recording his and their story. Studying their accounts, I noticed that they didn’t always agree with one another and that there were episodes in one version that were missing from the others. They all had difficulty verifying the vagaries of family lore, and none of their accounts was well sourced or cross referenced. I took up the challenge of analyzing where the information had come from and assessing its relative accuracy.

George’s son Arthur wrote his account first. After he died, and with Arthur’s account in hand, his brother G.P. put his thoughts to paper. On a trip to England in 2012, I looked up a descendent of G.P.’s who, to my great good fortune, possessed a treasure trove of materials I was loaned to copy. When more letters surfaced from his attic, another cousin scanned and forwarded them to me in the U.S. An unexpected pleasure of this exercise has been getting to know many of my Baker cousins, several of whom I correspond with regularly but have never met. James de Wesselow is one of them.

Arthur Baker’s daughter, Ruby, and his sister Louisa Baker’s grandson, Victor Binns, wrote their versions in the late 1960s. Victor was one of the last Bakers to work for the Baker firm in Istanbul. Before he retired to England, he was tasked by Unilever, then G. & A. Baker’s parent company, to write its history. Finishing it in 1968, he spent the ensuing decade compiling a most useful Baker genealogy, data that my husband has painstakingly plugged into Geni.com. Victor revised his account in 1984 to coincide with the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibit about the Bakers, From East to West.

Ruby and Victor wrote their accounts at the same time, but because of a disagreement between the Edwards and the Arthur and G.P. Baker sides of the family, Ruby wasn’t talking to Victor and they never compared notes. It was a great pity because Victor had a lot of valuable details to add. His information came from his grandmother Louisa Baker, Arthur and G.P.’s sister. She, it seems, had taken far more interest in her father’s story than either of her two brothers. Indeed, among her brothers growing up, she had the reputation of knowing a lot about other people’s business. By contrast, Arthur and G.P. open their accounts marveling at how little they know about their father, now that they came to think about it. Until that moment, on the cusp of their respective deaths, they had not given his life and legacy much thought. As a consequence of the family rift, therefore, important parts of George’s story were missing from Arthur, G.P., and Ruby Baker’s accounts. I had the unique opportunity to put it all together and round out George’s bizarre biography.

I also had an advantage over my former family historians, on whose shoulders I stand—the internet. With it, and assistance from another Baker cousin, a wizard at public records and genealogical websites, we uncovered new facts about George, secrets he had taken to the grave with him, secrets his descendants knew nothing about: That his family had been wretchedly poor, that his grandfather had disowned his mother when she became pregnant out of wedlock, that his parents had spent time in the infamous British workhouse, and that he had an illegitimate brother. George did some of his garden training with this brother, though whether he knew they were biologically connected is unclear. (G.P. was told he was George’s step-brother.) We also learned that George had been incredibly lucky through the course of his young life to have mentors steering him in the right direction, men of historical merit: nurseryman and horticulturalist Joseph Knight, British Ambassador Sir Stratford Canning, and Sultan Abdul Mejid. They each took a personal interest in him and were instrumental to his success.

The internet, and of course the Levantine Heritage Foundation website, allowed for ample research and fact-checking. Every day brought new dot connections and wholesale epiphanies. It was a seductive process, for it felt as if the Baker spirits had joined us in our quest and were guiding the way somehow. I could give you numerous examples of coming across crucial pieces of the puzzle by sheer happenstance, the chances seemingly a million to one. Like how that trip my husband and I took back to Istanbul in 1986 I won in a lottery. It was a fluke.

2- Was the reason to separate to 3 volumes the Baker dynasty story one borne out more of order, so different generations stories is not conflated or more of volume, that a book beyond a certain number of pages becomes almost unpublishable?

Gillian Mueller: It was both. My first thought was a trilogy. Book I would focus on my grandparents’ love story and extend through the Bakers’ evacuation from Constantinople in 1914 and their return in 1919 to pick up the pieces after World War I. Book II would go back in time to Elsie’s grandfather, George Baker, the original Baker to settle in Turkey. It would explore how he got hired as the British Embassy gardener and his transition into trade. It would trace the expansion of the The Shop, as it was called, and summarize the reasons for its collapse after George’s death in 1905. Book III is an anthology of Arthur Baker’s essays about Turkey set against the backdrop of his daughter Ruby’s firsthand account (bits of which are on the Levantine website). When my husband and I were in Istanbul in 2022, however, it was clear that George Baker had the widest appeal, and that struggling to summarize three generations in one breath prompted eyelids to droop. (Meeting with the British Consul General, we got no further than the pronunciation of ‘Penge’, where George’s brother lived). The aim now is to publish George’s story and see what interest it generates - read a summary:

3- George Baker was sent as the head gardener of the British Embassy to Turkey in 1848, and the British Government clearly saw this investment as worthwhile when a locally sourced gardener would have saved a lot of money. Do you think this is a reflection that there was an ‘status race’ with rival European powers as each tried to outdo each other in sumptuous Embassy buildings and summer palaces and the gardens were integral in that soft power projection to vie for the favour of the Sultan and the trade privileges that would flow?

Gillian Mueller: Definitely. And here again is an example of George’s extraordinary good fortune. Before and after his employment as embassy gardener, the practice was to hire locally. The cost factor aside, the Embassy had plenty of excellent local talent to choose from, be he Turkish or any other nationality. The Turks have a long tradition of beautiful gardens, but it was a different sort of garden. It was George who introduced the principles of a true English Garden—to include stretches of manicured lawn that required tons of care and watering—to the Turkish landscape. Yet the Turks had their own accomplished gardeners long before George Baker came on the scene. They were called bostanbaşıs. They were the head gardeners at the Sultan’s palaces and held a revered position at Court. Assuming Stratford Canning knew as much, and was aware that Abdul Mejid was an avid gardener, it explains why George was sent to Topkapi Palace to meet the Sultan, when Queen Victoria’s gift of exotic plants was presented to him, and why the Sultan would have been interested in engaging the new British head gardener in conversation.

But to your point, to George’s great advantage and impeccable timing, and for all the reasons you highlighted, in his case the Embassy’s choice had to be Kew trained and British born and bred. Stratford Canning would have insisted on it. Even George’s assistant was English, though locally hired. Mind you, had Queen Victoria’s courtiers and the Office of Works, who were pulling the levers on his appointment, had they been aware of George’s background, they might not have chosen him. Class divisions were too intrenched. But George kept his past to himself, and Joseph Knight, who put George’s name forward as the “ideal candidate,” and who was aware of George’s past, kept it a secret too. He, too, had started out as a lowly laborer and defied the odds by becoming a rich and respected yeoman, the one man to whom British nobility and aristocracy turned when they needed a top notch gardener.

4- George Baker was clearly talented and despite his very humble origins was presumably able to mix with different levels right up to the apogee of Ottoman / Diplomatic society, including Sultan Abdulmecit I and Sir Stratford Canning, the British Ambassador in Constantinople. Do we have any evidence to further that ability to mix he learnt some Turkish or dressed in a particular manner to suit who might be interacting with?

Gillian Mueller: When George stepped ashore at the British Summer Residence at Therapia in 1848, he took up residence with famed explorer Richard F. Burton, archeologist Austin Henry Layard, artist and limerick tsar Edward Lear, and visiting London courtier and aristocrat Lord Dufferin. (Layard and Dufferin would later return as ambassadors). Most nights, when the others weren’t invited to dine with the Cannings next door, they ate and drank together in the dining hall and shared their stories. George was a great story teller, apparently, renowned for his droll sense of humor. Combined with his Hertfordshire street accent, the others would have found him entertaining and in fact warmed to him quickly. Burton and Baker were “great pals”, Arthur reported, as were George and Layard, who invited him to be foreman on his second expedition at Nineveh. But George had fallen in love with Maria Butler by then and turned the offer down. Also, Ambassador Canning and Sultan Abdul Mejid were already whispering in his ear about getting into business and trade. Mejid was earmarking land behind Dolmabahçe Palace—the gardens of which George had been involved in designing—for him to establish a nursery business on a par with Joseph Knight’s Royal Exotic Nursery back in Chelsea. But Canning had an even better idea. He had negotiated an agreement with Mejid to allow British retail operations to commence in the Ottoman Empire, and he was keen for George open a shop. The implication of circumstantial evidence is that Canning went so far as to reserve two properties for George in the coveted British Consular Sector of Galata, one that became his residence, the other his first shop on Galata Square.

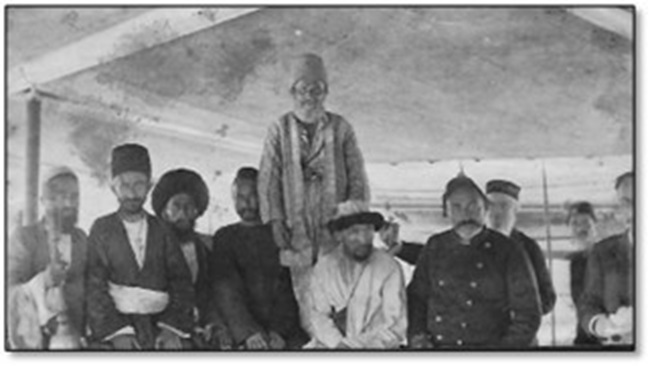

To your point, though, yes, George was a chameleon and adept at being one thing to the Sultan, another to Canning, and a third to anyone else. He was quick-witted and charming and made himself useful. Within a few years of his arrival, he had dropped his cockney accent in favor of a more formal, if stilted, Queen’s English, and he was picking up Turkish, French, Greek, and Armenian the better to serve his business aspirations. There is a photograph of George sitting in a boat with a variety of local types. He has just embarked at Rumeli Hisar and is on his way into town and to work. He is manning the tiller and is otherwise indistinguishable from the rest of the passengers. It took me a while to recognize him. When the occasion required, though, George donned his top hat and tails and looked the part of a true Victorian gentleman, while attending the opening of Robert College, for example, or an Imperial wedding at Dolmabahçe Palace.

His grandchildren recalled how, after his funeral, a crowd of Stambulites gathered at the dock in Scutari to escort his coffin up the hill to the Crimean War Memorial Cemetery (which, by the way, I’m almost certain he laid out in his former capacity as Embassy gardener). Reflecting Constantinople’s uniquely diverse population at the time, his grandson Cecil Edwards noted, “His funeral was attended by men of all rank, condition, race and religion, who had come to do honour to the worth and integrity of the Englishman, who had lived so long among them and whose ‘word was his bond’”. Victor Binns concluded his account, “George Baker’s impact had crossed all ethnic and cultural divides, and it was noted that never before in the City’s history had such a group of mixed faiths gathered in peace for a common purpose”.

5- Sir Stratford went above and way beyond his normal duties to open trading opportunities to George Baker. Do you think Stratford was ‘using’ George Baker as the ‘poster boy’ to open the way for other prospective British merchants who could also trade with the concessions Stratford was able to secure such as opening shops? On a wider remit do you think this was a local initiative, perhaps with an eye for ‘kick-backs’ or established British Imperial policy of creating multiple Shangai type of free ports across the world to further secure the route to India and other strategic interests?

Gillian Mueller: Whether George Baker was Sir Stratford’s poster boy, I couldn’t say. George was definitely one of the first British retailers to open for business in the Ottoman Empire, possibly the first in Constantinople, so in a sense, yes, Canning used George to set an example for others to follow. But the ‘others’ were already there in hordes, brought out from England as contractors in what I call the great British building boom, or with the fighting forces for the Crimean War. George had a lot of competition, young men just like him wanting to seize the day because, thanks to Canning, there were many geo-political forces working in their favour. But George was unique among them, I think, in that Canning and Mejid seemed to have a soft spot for him. They went out of their way for him, above and beyond.

James de Wesselow: Despite his rather grand name, in fact Sir Stratford Canning was the youngest of five to an Irish merchant based in London, who died when Canning was a baby. His mother would raise all five children in a small cottage in Wanstead, where he would holiday for the remainder of his life. Perhaps it was this parallel in Canning’s life, his relatively humble beginnings, the difficulties of a modest upbringing with multiple siblings in a small cottage, that attracted him to the recently appointed new gardener, George Baker, who had a harder upbringing but with some similarities.

Gillian Mueller: Canning and Britain’s broader vision was to do exactly as you say: secure trade routes to India for strategic and financial gain. Canning was a brilliant diplomat and strategist in this regard. I believe he could have done more for Britain had he had more time. But just as George was resigning from the Embassy and opening his shop in Galata, Canning was recalled to London and forced into retirement, a political casualty of the Crimean War. Long before British shops and department stores appeared on the Grand Rue de Pera, though, there were plenty of British merchants and financiers doing a brisk business in Turkey. They preceded George and paved the way for him, figuratively speaking and literally. They hired him to landscape their gardens, they lent him money to get his business off the ground, and they were grateful to have his retail outlets to shop in. They were prominent figures in the British Colony with names you know—the Hansons, Barkers, and Whittalls etc. Gravestones at the Crimean Memorial Cemetery where George is buried, and at the Protestant cemetery at Feriköy, tell the history of British trade in Turkey.

6- Do we know if George Baker made any efforts to seek native Turkish plants and bulbs for his horticultural business in Turkey or was it all sourced from Knights Nursery in England? Did his notebooks indicate any correspondence with plant hunters of the day?

Gillian Mueller: This is an interesting question. George’s diary includes lists of shipments from Knight’s Nursery of plants (mostly fruit trees) from all over the world for delivery to one or another of George’s first clients, like the Barkers. There is no mention of plants being sent back to England. That said, I know that George and Knight corresponded and there may have been some cross pollination on the topic of plants found in Turkey that were not as yet registered with the Royal Horticultural Society (of which Knight was a founding member). G.P. was an active member in the RHS and a full-fledged plant hunter, his brother Arthur serving as his guide, interpreter and specimen sketcher, when they trekked in the region together. Many flowering plants are named after G.P., which he either discovered abroad or cultivated in his garden.

7- You highlighted the 4 principles of George Baker’s business model which clearly worked just fine and perhaps was way ahead of his time? Was this discipline typical of Victorian businessmen or was he somewhat ‘modern’ in the design and implementation of these first principles?

Gillian Mueller: My Baker cousin James de Wesselow is more qualified to answer this question. George’s principles—of hiring family first, teamwork and pooling resources, growth at whatever cost, innovation, and diversity—all worked well for George and his sons, but may have been self-limiting as the business grew large and unwieldly. To stay afloat, G. & A. Baker Ltd. succumbed to absorption into the Unilever family after World War I. But the corporate style was anathema to Arthur Baker, who threw in the towel and returned to England. I’m convinced, nonetheless, that the spectrum of the business—to include imports, exports, retail and wholesale; contracts with the Turkish military, government and Imperial Palace; serving as representational agency for other European and American firms doing business in Turkey; other concerns like the oil well, flour mill and The Grand Garage; and of course the all-important carpet trade—this diversity is what kept G. & A. Baker limping along for fifty years after World War I, after the Capitulations were rescinded, after the Ottoman government was replaced by the modern Turkish Republic, and all the rules were changed. Most foreign businesses in Turkey before the war either left or folded during and after the war.

James de Wesselow: I’m not sure there is any evidence that George Baker had a grand well-thought strategy for his business empire, rather it grew organically and for good practical reasons of trust and hard work. I think George’s charming character helped, and the fact that he could trust his brother in England and later his sons in running the business, as well as various trades people he had grown to know when he was working in the embassy. Indeed, his son Arthur says in one of his diaries that George’s accounting systems were non-existent, and he was surprised that George made any profit at all.

Like many things luck played a big part and George was fortunate on a number of fronts: in his friendship with the ambassador, who allowed him, in his early trading exploits, to use the embassy’s rooms and no doubt a corner of the gardens for his early trading business in plants, linen and other wares. He was also fortunate in having a brother like James (not to be confused with his son and my great grandfather, James, who with his brother GP would form GP & J Baker Ltd back in England). Brother James was equally ‘get-up & go’ having risen in his linen wholesale business to be director, and then one of the judges at the great Paris Exhibition in 1873. He too escaped the poverty and bullying father, but unlike George, had had an education of sorts. His active encouragement and robust approach to George in getting him to strike out by himself in Turkey should not be overlooked. James would play a massive part early on, in getting George up and running with establishing the early trading business, not just linens but a variety of other goods, and the beginnings of the export of goods from Turkey back to England. As Gillian has stated above his easy relationship with the Sultan also helped, as did his friendships and business partnerships with the various ex-tradespeople who would become his business partners in the early days.

Later on, the decision to give each of his sons, GP and James the equivalent of £1.5 million in today’s money as founding capital wasn’t purely a benevolent act of a father, maybe he also wanted to diversify his business activities getting money back to England, as well as securing a proper trading route between Turkey and England and Europe for carpets. GP’s interest in fabrics, acquiring archives and horticulture was a happy byproduct. So the business principles were there but they had, I think, grown originally from experience and luck.

8- The successor business, J.P. & J. Baker business was also highly innovative and successful but things starting going wrong after the Second World War. Do you think like the earlier OCM business it was slow to react to changing market conditions and perhaps should have shrunk its operation to preserve itself through the lean times and perhaps the tradition of relying on family members to fill management roles had its own drawback as well?

James de Wesselow: Yes, I think this is all true. Unfortunately, I had wanted to get a perspective from the current management and ownership at GP & J Bakers but they are not willing, for whatever reason, to engage with me, and I haven’t pressed this. Sadly there are few other family members I can now ask but I have communicated with an expert on British fabric businesses who has added to my thinking on this.

The carpet business had shrunk and died for GP&J Baker, I believe in the mid-late twenties, perhaps a little later, as the OCM shareholding was diluted by the investing European bankers, poor decision-making by OCM shareholders and management including too much cost in employing European managers who behaved as if they were running a large government department, and broader geopolitical issues around government protection tariffs in favour of factory-produced carpets in England, Europe and the US.

So the business had to consolidate around its fabric business. This prospered in the first decades of the 20th Century, with the beautiful floral designs and colours hand-blocked on quality fabrics under the direction of GP and that still are the hallmark of their designs and fabrics. No doubt WW2 had had a big effect on sales as well as the ability to source linens and clothes. At the end of WW2 the trend for high-end fabrics, and the austerity in the UK and Europe, plus the rationing that continued for many years after the war, must have had a major impact on the business. Did Bakers keep up with these shifts and changing perceptions in their designs and price-points? There were new entrants competing in the same space. For example the interior designers, Colefax & Fowler founded by the well-known designers Sibyl Colefax and John Fowler, had their own range of fabrics which they sold to their clients. Perhaps Baker fabrics were being squeezed out of part of the market through new design, new print techniques and cheaper competition? I remember a discussion in my childhood about issues around the factory filling its order book with competitors’ products, the principal one being Warners, who were also in competition with Bakers. One of the comments that my mother Jane made was that orders for Bakers fabrics were getting delayed in fulfilment because of these outside contracts. The factory was one of the few remaining UK-based block-printers and had filled the factory time with competitors' products. The factory was still using the traditional block-printing processes, the last one being made in 1951, but had it kept up with technology advances, such as roller-printing, stenciling and screen printing? In the early 1960s new presses allowed for cost and other advances in mass-produced fabrics, which would have been a threat to Bakers as they hadn’t invested in new kit. Presumably imports from Europe and the emerging manufacturing centres would have contributed to these pressures.

Undoubtedly the management structure didn’t help in my opinion. It was run by the two cousins, Robin, son of GP and Ronald, son of James. Whilst Ronald had inherited his uncle’s eye for colour and was, I heard first-hand, a very good salesman, I think it fair to say he wasn’t a businessman. I’m not sure Robin possessed those qualities either. In the fifties it needed a managing director from outside the business to bring it together, consolidate, retrench, rethink the product range and sort out some of the issues in the factory. The family connection was still important and could have been retained but with a more hard-nosed approach all round to sort out the serious issues and face the new entrants to the market.

9- Is there more research needed or do you think the George Baker book is ready for publication? Are you looking at potential sponsors for both publication and a possible exhibition to go with it?

Gillian Mueller: Indeed I have a draft manuscript (precis: Prospect Place) that I am going through now to fact check, polish, and add photographs. Publication is the objective, as mentioned, and a possible exhibition to go with it would be fabulous if we get that far. In our interview with the Consul General, he did propose the British Palace aka Pera House as a possible venue for just such an event.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer