The Interviewees

Interview with Dimitris Kousouris, September 2024

1- How connected were the Catholics of the Cycladic Islands and Chios to the other centres where Catholic communities also resided. Can you trace in family records people moving back and forth to ports such as Constantinople, Smyrna, Alexandria, Trieste etc.? Was this sea commerce their main income or were they mostly farmers and fishermen on these islands?

The Catholic communities of the Aegean archipelago were interconnected with other Catholic communities in the Eastern Mediterranean in various ways, through the networks of maritime trade, of the diplomatic missions, of the Catholic church. A number of recent studies drawing on the communal and church records shows an increased degree of mobility between the islands and the Levantine urban hubs, especially after the mid-18th century. During this period, beyond the local rural economy oriented towards agriculture and fishing, the islands developed closer links with European trade and business networks operating in the region. Thus, in addition to members of prominent families with commercial and other business activities, who sometimes represented the insular communities before the Ottoman administration, islanders appear to be employed as priests, teachers, low-ranking employees in the delegations or diplomatic services of the Catholic Church, France or other European countries, but also as independent craftsmen or small professionals.

2- The Catholic presence in wider Greece goes right back to the Crusader times and was there a gradual coalescence of this presence to the relative protection of these islands, so moving away from the mainland over centuries?

Indeed, the Catholic presence dates from the time of the Crusades, but the character and the limits of this presence was neither unambiguous nor immobile. First, one should bear in mind that allegiance to the Holy See was subject to the changes of imperial rule in the region through the centuries, the demise of the Latin empire, the transition to the Ottoman rule etc. With regard to the Ottoman period in particular, recent research has shed light on two aspects of intra-Christian relations that still require more systematic research. ‘Top-down’ approaches often reveal a process of a so-called ‘Orthodox reconquest’, i.e. a systematic attempt on the part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to use its power within the Ottoman administration to claim not only the souls of the flock but also episcopal sees, churches, their landed properties and the revenues derived from their appropriation. At the same time, others, more ‘bottom-up’ scholarly approaches to different forms of communicatio in sacris, double altar churches and other common places of worship, religious conversions or double allegiances, highlight the fluidity of the boundaries between the two confessional communities. Truth is, however, that the consolidation of the fiscal and political role of the Ecumenical Patriarchate during the centuries of Ottoman rule marked a period of withdrawal and decline of Catholicism in the Levant, as it has been repeatedly noted in various reports of the Catholic church of those times. Smaller islands and insular communities made no exception, that is why at the end of the Ottoman era in the Archipelago there remained only four islands with a substantial Catholic population on them.

3- Clearly it was easier for the Latin community of these islands to retain their Catholic identity when under Ottoman rule as they were given a large degree of autonomy and they benefitted from the millet system that kept them out of the constraints of sharia law. Were the priests that served this community locally derived or did the various Catholic orders send out priests from France / Italy? Was there a degree of rivalry between the different Catholic orders and were local tensions created as the community was Greek speaking and presumably carried elements of that local culture?

The preservation of a distinct Latin identity and community in four of the Cycladic islands (Tinos, Syros, Naxos, Santorini) in was certainly due to the distance from the imperial capital, but also to particularities of each case: Tinos remained under Venetian rule until 1715; in Naxos and Santorini Catholicism and Latin identity derived from feudal rights and privileges of the Duchy of the Archipelago that had been accommodated within the Ottoman context; Syros, the only island with a Catholic majority, one in which the Ecumenical Patriarchate had not managed to set a foot until the early 19th century, is a most instructive case concerning the economic and political functions of the Church within the local community.

Priests were both local and of Italian/French or other origin. Actually, post-Tridentine church systematically invested the Ottoman Levant with Catholic missionaries. Since the beginnings of the 17th century, the Catholics of the Levant would send their children to the schools founded by Capuchins, Jesuits, Ursulines etc. or to Italy, the Greek College of Rome and other Catholic institutions. In the islands, education was usually provided mainly in Italian. Language was not an issue for the everyday communication in those multilingual communities. Missionaries and priests were required, or obliged by the circumstances, to speak or to learn the vernacular Greek while an average inhabitant of the Archipelago was able, according to Della Rocca on late 18th century Syra, to establish some kind of communication in Greek, Turkish, Italian or French. As elsewhere, rivalry between different orders or between orders and the local hierarchy could arise occasionally, due to local tensions or broader developments (as the suppression of the Jesuits in 1773). At the same time, through the ideological bias of the Catholic church that identified itself through its evangelizing and civilizing mission, local culture and practices of syncretism were often considered as symptoms of corruption of the Christian faith by an oriental and/or islamic culture.

4- Were the French the sole protectors of the Latin communities of the Eastern Mediterranean or were there periods when for example the Austrians had a sway and do you think the French were conflicted when the Greek rebellion started as they were keen to keep their long-standing peace with the Ottomans and the trade that followed from that?

Although the French were not the only Europeans claiming the protection of Catholics in the Empire, they had acquired a prominent role in the protection of those communities during the 17th and the 18th century. Of course, after the fall of the Serenissima and, even more so, after the defeat of Napoleon and the Congress of Vienna, the Austrians claimed their share in the Levantine commerce and in the political and cultural influence exercised in the region. The case of the Greek War of Independence, during which France and Habsburg Empire established a sort of shared responsibility regarding the protection of the Archipelago Latins illustrates not only the growing influence of the Habsburg Empire, but also the inherent contradictions of the French policy in the region once the creation of a Greek state became inevitable.

5- Do surnames matter today or in the past in Catholic self-identity as presumably the population always had a mixture of Italian and Greek surnames through generations of intermarriage?

Surnames with an Italian or other European origin are a distinct trait of local insular identity. Hence, when, appointed as administrator of the Syros’ diocese during the Greek revolution, Luigi Maria Blancis promoted a status of free port for the island, he highlighted those surnames as proof of the European origins of the islanders. Nowadays however, since such names are born by Orthodox and Catholics alike, they are not strictly or exclusively linked to a Catholic identity.

6- Did some of the Catholic priests from Tinos and other islands rise to prominent roles in bigger centres such as Smyrna and have they left writings behind of significance?

The appointment of priests in leading positions in other dioceses was not an unusual phenomenon. Monsignor Russin for instance, Bishop of Syros at the outbreak of the Greek Revolution, was a native of Tinos. Yet, those who rose more often to prominent positions of the Levantine Catholic hierarchy were the Chiots. This wealthy island that had remained for centuries under Genoese control, with a population comparable or even larger that of the neighbouring city of Smyrna, had been invested with missionaries since very early years after the Ottoman conquest, in the late 16th century. A great number of scholars from Chios rose to prominence amongst the Jesuits and other religious orders during the 17th and 18th centuries; during that same period, a great number of Bishops, Archbishops and Apostolic Vicars in the islands, in Istanbul and Smyrna were natives of Chios.

7- After the Greek revolution with all the violence on both shores of the Aegean a large number of Orthodox Greeks arrived on these islands where the Catholic populations were significantly diluted and no doubt resulting in local strife such as land claims, church property ownership? To what extent were these dealt with locally or was the new Greek state involved to the advantage of the new comers and did the French consuls etc. try to manage the situation?

I deal with this subject in my forthcoming book, focusing mainly on the case of Syros. Mobility of Christians and Muslims to and from both sides of the Aegean during the Greek War of Independence was intense. Hence, several tens of thousands of Greek Orthodox fled Ottoman reprisals in the Asia Minor coastal region, the islands (Chios, Psara, Kasos, Crete and elsewhere) or the Peloponnese later on, seeking refuge on the islands. As the Latin community of Syros had declared its neutrality in the conflict since the outbreak of the Greek revolt, this meant the island became a most attractive destination, first for merchants who moved their businesses there, and gradually for thousands of refugees and adventurers of all sorts who found a safe haven there and opportunities for work and profit. Since all Catholic communities declared their neutrality and claimed French protection, tensions between them and the Greek insurgents occurred from early on, usually around incidents of rescue by the Latins of Muslim prisoners transiting the Archipelago eastwards. As a result, Latins were stigmatized by the insurgents as turkophiles. This stance was corroborated by the subsequent refusal of the Latins to comply to the collection of the annual tithes by the Greek provisional government as well as not sending representatives to the new National Assembly.

The various local vice-consuls of France were actively involved in the implementation of this neutrality and the defence of fiscal immunity of the Catholics - a line that soon proved untenable for the French government, which had to circumscribe the protection provided to the Latins within the limits of the free exercise of the cult and equal treatment of communities. Hence, in 1823, all four Latin communities of the Cyclades started paying tithes and other forms of extraordinary taxation to the Greek insurgents. Incidences of anti-Latin violence multiplied, mainly in the islands of Syros and Tinos, which hosted the two largest communities representing 80% of the Archipelago Catholics. The seizures or profanations of Catholic chapels, thefts or destructions of crops, but also physical attacks including the occasional murders were recurrent in 1823-1827.

Syros, the only Cycladic island excluded from the territories claimed by the Greek insurgents in 1822, was recognized as Latin, thus neutral, territory. The course of its integration into the nascent Greek state provides a panorama of the various forms of conflict and coercion, that sometimes took the traits of conquest and colonization. Once, after the massacre of Chios, with Syros becoming the main hub of trade in the Archipelago, the Greeks attempted to gain control of the port and its revenues. The first attempt to take control of the port and to attack the citadel of the Latin community in early 1823 was led by Nestor Faziolis, a Greek Orthodox ship captain from Cephalonia. This first assault was repelled by the Syriots and by the intervention of a ship of the French division du Levant, was followed by a second one and a new French intervention. When later on, the same Faziolis was dispatched to Syros as chief of the local police by the Greek government, the French, delivered him to the British and issued a formal warning to the Greek government. During the same time, however, the Greek insurgents had acquired de facto control over the port and the fleet and had forced the payment of the tithes and various extraordinary taxes by the Latin community. Since the latter kept affirming their allegiance to the Ottoman Porte on all occasions, they remained subject to double taxation for the following few years. Meanwhile, the mass arrival of refugees and settlers of all kinds brutally changed the demographic equilibrium. By late 1824, the number of settlers in the port of the island was five times or even more as high as the 4 to 5 thousand native Latins. As the port was becoming an Eastern Mediterranean Eldorado, where everything, including piracy booties and slaves, could be purchased, raids in the countryside by land or by sea became recurrent, often leading to bloody incidents. The lands around the port of the island were leased or purchased by rich settlers; however the settlement and expansion of the new town, entailed that large chunks of church or private properties were usurped or trespassed on. A last French intervention against the local Greek Eparch (diocese) in 1826 marked the beginning of the end of the French claims for protection. At the same time, the access of the local community to the port and even to water supplies and other vital resources became limited. After 1827, the newly established tribunals of the Greek state did examine some claims of the Latins and did occasionally grant some compensations, but did not reverse the new state of affairs.

8- These islands had their own civilian administrators including vice consuls, dragomans presumably heavily drawn from the Latin community, clearly also serving the commercial interests of the community. Did some of these leave a mark on history and was there ever a debate on whether the islands should be governed independently?

Local vice-consuls of European powers, who were often members of prominent Catholic families of the islands, were heavily involved in commercial activities that resulted in communal and private gains. A number of recent studies brings into light the involvement and functions of those consular agents within the local societies but also the commercial and diplomatic networks of the Europeans. However, despite their pivotal role as links, connectors, facilitators or translators, they were rarely involved in political endeavours.

Of course, that the islands were de facto a sort of tributary republics with a loose connection to the imperial capital was obvious, not only for French merchants and missionaries, but also for the islanders themselves. A distinct Latin identity had been forged on the basis of religion, indigenousness and a shared allegiance to the Sultan and the French King as protector of the Catholic faith. Hence, on the basis of such a distinct identity, when the events of the Greek Revolution brought up in the political agenda the territorial status of the islands, the prelates of the Catholics in concert with French officials and local consular agents promoted various projects of autonomy for the islands or of a special status for the Latins.

9- Did the Latin community of the islands leave much in the way of secular writings and if so in which language and script?

Well, most known scholars coming from those communities were theologians trained in Catholic schools of the region or the Italian peninsula, but their work often went beyond religion. Again, Chiots held a prominent position among them. Hence, in the 17th century, a most emblematic figure was Leo Allatius, a Catholic scholar and theologian coming from an Orthodox background, who wrote extensively on treatises on the theological and doctrinal resemblances and differences of the two churches, supporting their union. As a librarian in the Vatican library, his works included editions, translation and publication of Greek manuscripts, medical treatises and even a catalogue of the musical dramas in Italian produced and staged in the 17th century. Another emblematic Chiot of the next (18th) century was Tommaso Stanislao Velasti, a Jesuit theologian and philologist, who authored among others a treatise on the pronunciation of literary Greek (in Latin), poetry (in Greek and Italian), as well as popular catechisms in vernacular Greek printed in Latin script, the so-called Frangochiotika. There were of course some outsiders who settled among those communities, like the Levantine Abbé Della Rocca who lived in Syros and published in 1790 in French a treatise of beekeeping in Syros which contains valuable information about the social and economic situation of the island. In any case, the literary production of those communities has so far not become the object of a more systematic approach and there is no doubt still a lot more to discover and learn about it.

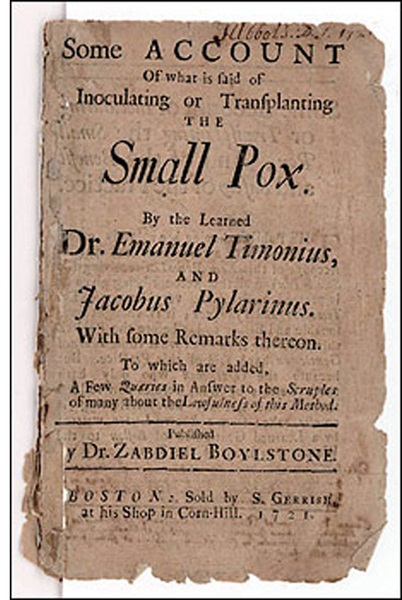

There were of course others, like dragomans and scientists who rose to prominence, like Emmanuel Timoni, offspring of a famous family from Chios, who, together with his colleague from Cephalonia Pylarinos, became known in the UK and all over Europe in the beginnings of the 18th century for their writings on inoculation against smallpox.

Leo Allatius

The book cover of the writings of Emmanuel Timoni & Pylarinos, printed 1721.

Mons Andrea Policarpo Timoni (14 March 1833, Smyrna – 1st August 1904, Smyrna)

Timoni family covers a very wide history in the Levant, dragomans, doctors, etc. Mons. Timoni contributed to the discovery of Mary’s House at Ephesus. We find them in Chios since 1521, and in Constantinople since 1626. Vincenzo Timoni was the doctor of Sultan Valide in 1626 and the favorite doctor of Sultan Murat IV in 1639. - further information on this family:

10- The Capitulation treaties during the Ottoman Empire gave the Consuls and their protégé entourage privileges of tax exemption that was clearly open to abuse. Do we see a rising merchant class on these islands where the beratli dealing in overseas commerce and were these individuals all ‘native’ or were there also ‘Levantines’ active in shipping etc. based in the islands?

Of course, patents of protégés could often be purchased and the limits of protection provided would vary according to the specific local circumstances and conjunctures. As mentioned already, during the second half of the 18th century, a rising merchant class did appear in the Eastern Mediterranean. Its composition included regional actors from the trade hubs of the Adriatic sea (Venice, Trieste, Ragusa/Dubrovnik), but also people from other parts of the Italian peninsula, from France, Netherlands and elsewhere, active in overseas commerce and/or other business in the Ottoman and the Russian empires. The exact composition and character of this rising merchant class is still an open question for historical research.

11- You have also done work on Frangohiotica which was the Latin script version of Greek used informally in many of these islands in the past. Did this dialect have its own evolution in terms of loaned words and idioms borrowed from the Italian and French you detect, or regional variations such as in Chios?

The production in Frangochiotika constitutes a most important and under-researched aspect. The term draws its name from the Catholic priests and missionaries from Chios, who applied this practice since the late 16th century with the intention to overcome the linguistic boundaries and to reach “the uneducated and the children” as well as those Greek speakers who had received their education in schools of the Catholic church, religious catechisms. But also dictionaries and other texts in Frangochiotika were written in the vernacular and recorded its local idioms, mainly that of the region of Chios and Smyrna, that appears to be the centres of their production and circulation.

However, Frangochiotika books were also printed in Istanbul, Venice, Rome, Paris or Vienna. Τhis geographical dispersion suggests the links and networks between these heterogeneous Catholic communities with the networks of the Holy See, the Serenissima, the French and Habsburg empires. At the same time, the persistent use of the Latin script in printed and handwritten Greek from the age of the Catholic Counter-Reform and of the Ottoman conquest to that of nationalisms, renders those works a rare source of knowledge about popular religiosity, the multiple interactions within the multilingual communities of the Eastern Mediterranean, and the distinct, hybrid identity of the Greek-speaking Latins of the Ottoman Levant.

What is more, the Latin script was used to write the Greek language in a plethora of manuscript sources, ranging from literary texts to correspondence, contracts, wills, dowries, court decisions, petitions or even prayer books written by the local clergy or lay members of religious confraternities. As these sources have not yet been systematically studied, we are about to prepare a collaborative project with the aim to list, index and make them accessible to scholarly research as a corpus. For that purpose, we recently organised an international workshop with the participation of the Austrian Academy of Sciences, the National Research Hellenic Foundation and the Jesuit Library of Greece, whose papers will soon appear in The Historical Review.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer