|

|

John Seager ended up obtaining the agency for the Cunard shipping company in 1852, which remained in the family for 80 years, the company did not survive the crash of 1929 and was closed soon thereafter - information courtesy of J.P. Giraud.

Four Generations

EDWARD SEAGER

Born 1809, Poole, Dorset. Shipowner and shipping agent. First Seager to settle in

Turkey. Moved to Constantinople with family, 1847/48. Introduced steam boat haulage

to Bosphorus. Handled shipping for British military to Crimea, Russia. Died 1854

(aged 45), Balaclava, Crimea.

JOHN SEAGER

Son of Edward. Born 1838, Poole, Dorset. Moved to Constantinople as a young boy

with family. Became wool/mohair trader, obtained Cunard shipping agency. Died

1907 (aged 69). Wimbledon, London.

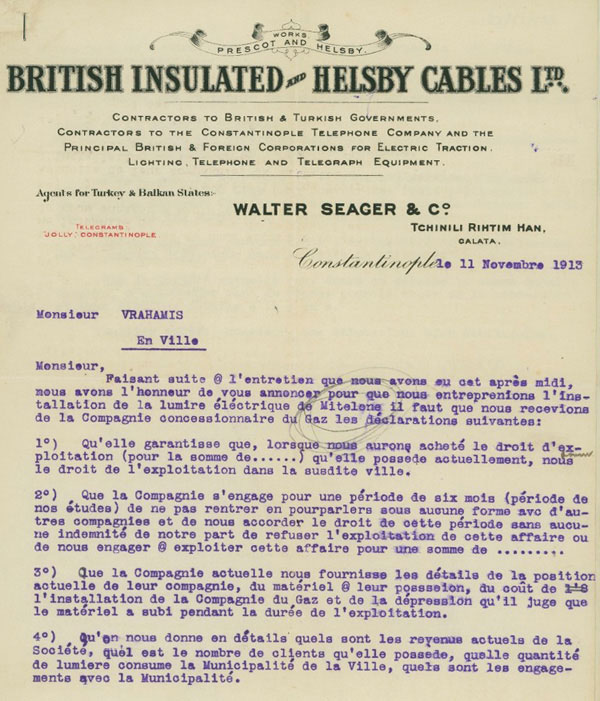

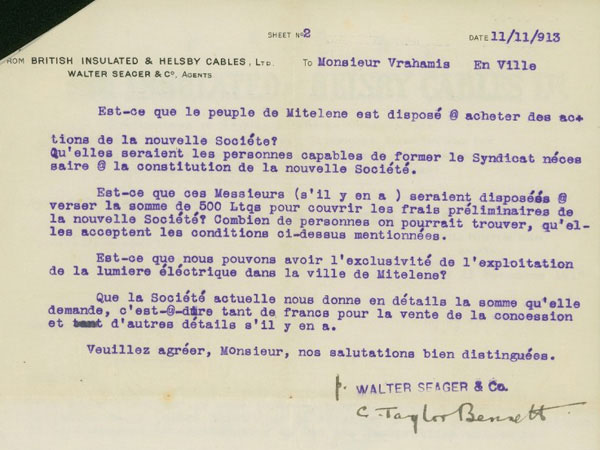

WALTER CONSTANTINE SEAGER

Son of John. Born 1876, Bebek. Steamship agent (Cunard) and other businesses.

Founded Walter Seager & Co. Died 1934 (aged 58), Bebek.

CEDRIC SEAGER

Eldest son of Walter Constantine. Born 1902, Bebek. Married American citizen and

emigrated to U.S.A., 1935. Joined U.S. forces, WW II (posted Istanbul). Worked for

State Department (USA) after war. Died 1959 (aged 57), Rabat, Morocco. Buried at

Arlington Cemetery, Washington, DC. (See more detailed biography).

WILFRED SEAGER

Second son of Walter Constantine. Born 1904, Bebek. Joined OCM. Spent many

years in Persia. Then Director, OCM London. Died 1977 (aged 73), Seven Oaks, Kent.

WINSOME SEAGER

Only daughter of Walter Constantine. Born 1905, Bebek. Married John Ivor Tennant

GREEN, OBE, Royal Navy. (He was young officer on HMS MALAYA, which took away

last Ottoman Sultan Mehmet VI Vahdettin from Constantinople, 1922). Died 1972

(aged 67), Blackheath, London.

EWART SEAGER

Third son of Walter Constantine. Born 1907, Bebek. Married American citizen (sister of

Cedric Seager wife) and emigrated to U.S.A. Also joined U.S. forces, WW II (posted

Turkey). Worked for CIA after war. Died 1977 (aged 70), Rockport , Mass. Also buried

at Arlington Cemetery, Washington, DC.

HAROLD SEAGER

Fourth son of Walter Constantine. Born 1909, Bebek. Worked for British Intelligence

(Cairo) WW II. Joined U.K. Foreign Service after war. Died 1985 (aged 76), Shoreham,

Kent.

JOHN SEAGER

Fifth son of Walter Constantine. Born 1912, Bebek. Worked for BP Turkey, Istanbul.

Retired to the U.S.A. Died 1974 (aged 62), Olivet, Michigan.

|

Biography

Cedric H. Seager was born a British subject in Istanbul in 1902. His family was important in British spheres of influence in that area, and he served in his early years as a director then board chairman of Walter Seager & Co. Ltd., a family firm which, among other things, was the agent for Cunard Lines.

In 1931 he married an American girl, then emigrated to the United States where, from 1935 to 1942, he was a writer and lecturer on the Middle-East.

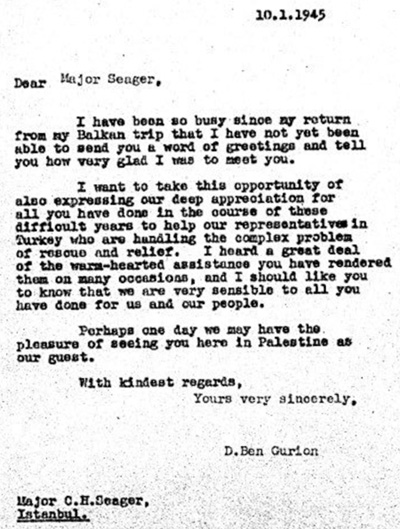

In 1942 he became a naturalized American citizen and served in the army from that year through 1945. He was sent to Istanbul as assistant military attaché and attained the rank of lieutenant colonel. He was also part of the OSS at that time, and became quite involved with the rescue work of the Jewish Agency. He made a number of contacts within that agency, especially with Teddy Kollek (later mayor of Jerusalem), with whom he developed a friendship. He is extensively mentioned in Tuvia Friling’s book: ‘Arrows In The Dark: David Ben Gurion, the Yishuv leadership, and rescue attempts during the Holocaust’.

After the war he became assistant director of Trans World Airlines in the Middle East, based in Greece, where he helped re-establish the Greek airline T.A.E.. In 1947 he joined the U.S. Economic Aid Administration (later ICA), becoming chief of the Near East, South Asia and Africa Operations branch in 1955. In 1957 he was sent to Morocco to head the ICA operations in that country, where he died at his post of a heart attack, in 1959, at the age of 57. He is buried at Arlington Cemetery.

By Cedric H. Seager

There is a picture of me somewhere taken sitting on Grandpa Seager’s knee. I was two years old at the time and, if I may say so, rather good looking. The features have deteriorated since.

I don’t remember my grandfather at all. He died, broke, in the following year and I have always held it against him, perhaps unfairly, that he ruined what might have been a brilliant career for my father.

He must have had sterling qualities. He was still in his teens, a newcomer to Turkey, when his own father died and he was shouldered with the responsibility of supporting his mother and a swarm of brothers and sisters. I don’t know why he never returned to the family stronghold in Dorsetshire; perhaps there had been a quarrel. If so I never heard of it, but neither have I ever had any contact with the Dorset clan whose traceable lineage antedates the Domesday Book.

His father, my great-grandfather Edward, sailed from Poole in the early years of the nineteenth century in search of adventure. There was no disgrace in that. It was in the family, if not to say the national, tradition. A good many other Seagers had sailed out of Poole on the same impulse. One of them was with Sir Richard Grenville in the Azores shortly before the cocky little REVENGE fought the great fight Lord Tennyson immortalized. Later, he and his brother took their own ships into battle against the Spanish Armada; there’s a tapestry in the House of Lords depicting Adam Seager’s frigate the GOLDEN NOBLE. A Seager went to India and became a High Court judge. One was with Nelson at Trafalgar. His brother was a Captain in the Madras Presidency. With such material as this was the grim game of Empire played, beginning with Elizabeth and ending with the death of Victoria. Nor does one have to be an imperialist to be proud of them.

Great-grandpa Edward went to Newfoundland, of all places. Or perhaps he didn’t exactly “go there” but having fallen in love with Ann Pack, the daughter of an island judge, found it both convenient and profitable after his marriage to settle in the small port of Carbonear, N.F. In due course he became the owner of a fleet of ships and the father of a large family.

In 1853, the Crimean War having broken out, Edward Seager placed his ships at the disposal of the British government for transport purposes. On one of them he voyaged as far as Constantinople, taking his brood along with him. At the Dardanelles they clashed head on with Boreas, the stubborn wind that bothered Jason so much when he pioneered this way. It blew an idea into Edward Seager’s head.

In view of my own inquisitiveness I think it is curious that I knew nothing about this brainwave of his until eighty two years later. One autumn afternoon in 1935, the way fate leads one by the nose I found myself at Burnaby Lake in British Columbia supping a dish of tea with two incredible old ladies, his daughters.

Apparently the one thing about the old man of which they were most proud was that he introduced steam to the Bosphorus. When he discovered that the prevailing wind at Bosphorus and Dardanelles was northerly, and that it blew through both straits at a steady clip six days out of seven, he sent to England and bought a tug. It didn’t do much business at the Dardanelles, but for a while, on the Bosphorus, it was a gold mine, towing fishing fleets out of the harbour of the Horn into the Black Sea.

One wonders if he ever intended returning to Newfoundland. The old ladies seemed not to know when I asked them. His purchase of the tug suggests that the Bosphorus already had him in thrall and that he had turned his back on the cold waters of the northern Atlantic. Who knows? The point is academic because he was fatally inspired, as the war dragged on, to visit the Crimea. He joined the land forces on a crazy impulse a few days before Balaklava, and that was that. Some friendly officers recovered his body and brought it to his widow for burial in the cemetery that was given the name of Crimean Memorial, at Chalcedon across the Bosphorus from Constantinople.

Edward’s son John was a properous merchant, a dealer in mohair and wool. He married the daughter of a Yorkshireman, James Binns, who had come out to Turkey at the Sultan’s invitation to build and operate the first Turkish cotton factory. Of this union my father Walter Constantine was born, the youngest of seven children.

I judge that Grandpa John Seager, this same with whom I was photographed, was endowed with all the gravity of that antimacassar era. The Widow of Windsor had set a standard of stuffy rectitude which it was the duty of all her subjects to maintain wherever they happened to be.

“Remember, dear boy,” Grannie Binns said to me --oh how painfully often! “You must always be an example to the natives.”

She gave me Pilgrim’s Progress to read; I suppose for a textbook.

In a kindly, well-meaning way all these good people were tarred with the brush of hypocrisy. They spend half an hour before brekfast every morning singing hymns, the Greek and Armenian servants being brought in to support their devotions. Not even the missionaries were quite so fervid.

Such punctilio was surely--or is it ungracious to confess it?--the tiniest Pharisaical. Well, perhaps not deliberately so. Yet religious conviction ran never so deep in their hearts as the underlying consciousness of their greatness as Englishmen. Every day in every way this superiority had to be manifested. I’m not saying, mind you, that the system didn’t have its points. It is easier to attain greatness through belief in a heritage of greatness. But insincerity, however bottled, is a sour wine.

On the floor of the New York Produce Exchange, in the year of the Wall Street collapse, I met Grandpa John’s cousin, a legendary figure, then well along in his nineties, who had won and lost half a dozen fortunes but whose name was never mentioned in the family because at some point in his hectic career he had made an unhallowed voyage around the world with a Spanish diseuse.

“So you’re John’s grandson,” he mused. “Dear John. Splendid fellow. Asked me to spend a week with him in Bebek once but after breakfast the second day I said ‘Cousin John, I’m moving out. There’s too much damn praying and psalm singing in this house to suit me’”.............

In the end Grandpa John broke the code he had observed so faithfully throughout his life. According to the code one lived respectable and, dying, left a handsome package of Consols and kindred gilt-edged securities to one’s heirs. Grandpa left only a legacy of debt which, through circumstances that are of no consequence now, were shouldered by my father, his youngest son.

Somebody told John, who had never flung a penny at the moon in all his life, that there was a fortune in manganese to be dug out of the Caucasus Mountains. There was. Only Grandpa didn’t find it. He spent two years and far more money than he possessed looking for it, his health broke down, he sold out his holding for a song to his two Greek clerks. and he returned to Turkey to try to get back into the wool and mohair market. It was too late. He mourned his folly for a while and then he died. The two Greek clerks reaped a colossal harvest.

This tragedy hit Father hard. He had dreamed of studying the law in England, keeping a weather eye open for a seat in Parliament. I don’t doubt at all that he could have made a name for himself. He was a good father. A fine head on a tall body, raven black hair and honest grey eyes. He had the hands and slender fingers of an artist. But there was no music in him. “A Beethoven sonata and a boy beating on a tin can are one and the same to me,” he once remarked ruefully.

Father was a keen student of history. He was gifted with tremendous industry and possessed an encyclopaedic mind. Grandpa John approving, he was all set to go to England when the Caucasus venture ended in failure. He went to England all right, but only for the unhappy purpose of negociating with Grandpa’s creditors. He was still short of his twentieth birthday. The plumes of the ruffled gentlemen were soothed, Father promising redemption ......

He made a strange excursion before that dreary trip to England was concluded. Strange and pitiful. He had visited Liverpool to interview the Cunard Company and persuade them that their interests in the Levant would not suffer if entrusted to a youth of his tender years. His job done, he entrained for Chester one evening and hired a bicycle from an ironmonger in that Cathedral city. On this he pedaled out to Hawarden Park where Gladstone, the great Liberal statesman, lived.

Father leaned his bicycle against the wall of the estate. Darkness had fallen. Groping his way towards the house he found an ancient oak opposite a lighted upper story window and settled himself in the branches. Luck was with him. The window belonged to Gladstone’s study and the Grand Old Man himself was seated writing at a desk.

Father gazed his fill at that noble, leonine head. One can only conjecture the thoughts that passed through his mind. It was an act of worship as well as the snapping of a dream. He sat there until a servant came with a sconce to light the dying warrior to his bed; then, returning to Chester, Father took train to London and so, some days later, to Bebek. He named one of his sons after his boyhood hero.

Father and Mother knew and loved each other all the days of their life. I don’t know how to say that other than sentimentally. They played together as children, they bought their first boat together while they were still at school, and it never occurred to them that they would marry any but each other.

Their numerous relatives in the valley were not so enthusiastic. Numerous is right. In an age when a fellow was considered to be almost a eunuch if he didn’t produce at least eight offspring, all the men of the Binns and Seager tribes were commendably prolific.

Father and Mother were first cousins, which was barrier enough. But more than that, Mother, who was petite and as a child frail, was not expected to outlive her twentieth year. “Poppycock,” said Father. And “Nonsense,” exclaimed Mother. Parental opposition was strong enough just the same to postpone a final decision until the events of a certain night resolved the problem.

They had rowed far up the Asiatic shore of the Bosphorus and had paused in the shadow of a gloomy yali bordering the water. After a while their presence was detected and a gruff voice ordered them to begone. Father made an impudent reply and hung upon his oars. God knows what manner of evil invested that waterfront house; it was one of many that would tell strange tales if walls could speak.

Presently the creak of oars and the splash of driven water put Father on the alert. From a side door giving onto a narrow inlet a titanic Negro had vaulted into a moored skiff and was bearing down on them. He carried a knife between his teeth. His intention was only too obvious. Father rowed as he had never rowed in his life before while Mother, at the tiller, kept him where the current ran most swiftly. They outdistanced their pursuer, but the incident jolted them out of an easy rut and they agreed that night that they would marry before the month was out.

Then, on his wedding day, a gaggle of village busybodies, backed by the local G.P., told Father that if he ever allowed Mother to have any children he would be as guilty of murder as the court that sat in judgement on the martyr Maid of Orleans.

They had six children and Mother, bless her brave heart, flourished.

|