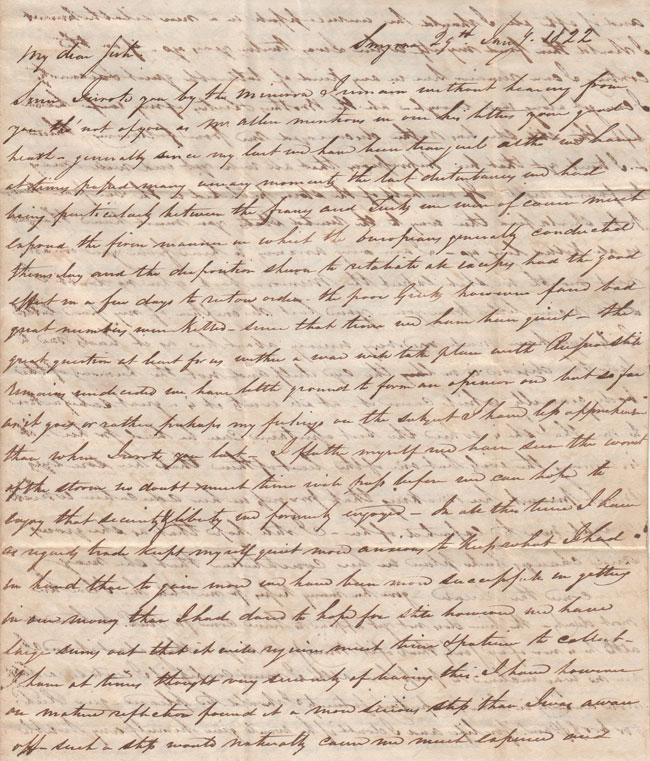

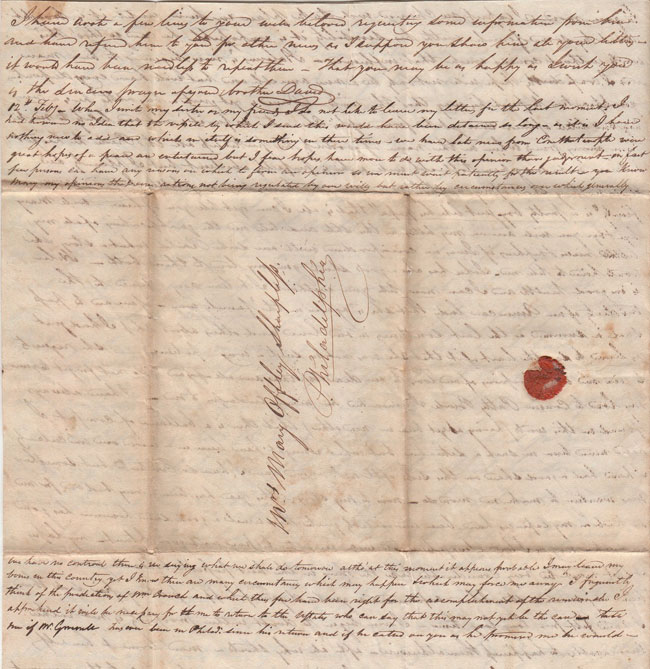

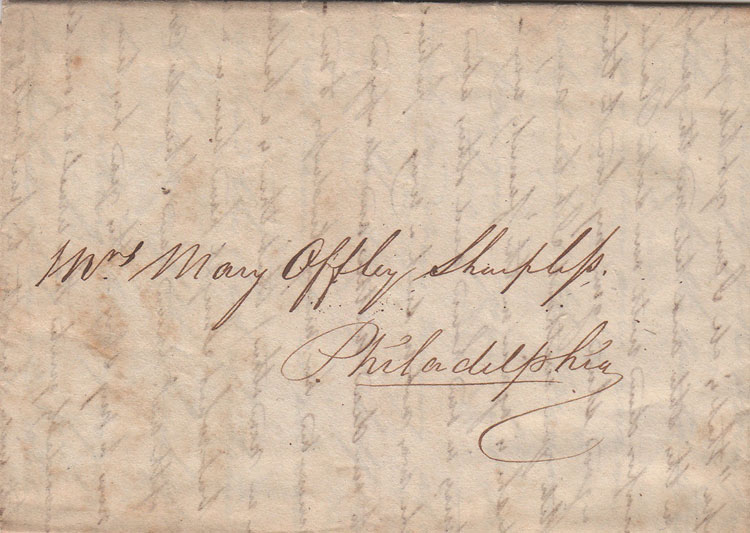

Letter dated at Smyrna, Turkey, January 29, 1822, (and continued on Feb. 12th, as the ship he hoped to send the letter on, was detained) from David Offley, to his sister, Mrs. Mary Offley Sharpless, at Philadelphia, Pa.

Folded letter was privately carried by ship to the U.S., and has no postmarks.

He writes of the attacks on foreigners in Smyrna by Turks (this violence was sparked by the Greek uprising, a war which lasted until 1829, culminating in the establishment of the modern Kingdom of Greece), and how the Europeans actions of retaliation helped restore order, but that the Greeks fared quite badly, with many killed. All of his wife’s family fled Smyrna (they were Greek), but she persuaded him to remain in the City. He also discusses fears of a possible war with Russia. There is also great content concerning how his business has suffered because of the trouble, and also much concerning his 3 sons, Richard, Holmes & David, who came to live with him in Turkey, and his expectations for their success in the world. Much more.

Includes:

“Since I wrote by the Minerva, I remain without hearing from you, tho’ not of you, as Mr. Allen mentions in one of his letters your good health.

Generally since my last, we have been tranquil, altho’ we have at times passed many uneasy moments. The last disturbances we had being particularly between the Francs and Turks. We were, of course, much exposed. The firm manner in which the Europeans generally conducted themselves, and the disposition shown to retaliate all excesses, had the good effect in a few days to restore order. The poor Greeks, however, fared bad. Great numbers were killed. Since that time, we have been quiet. The great question, at least for us, whether a war will take place with Russia, still remains undecided. We have little ground to form an opinion, and but so far as it goes, or rather perhaps my feelings on the subject, I have less apprehension than when I wrote you last. I flatter myself we have seen the worst of the storm. No doubt much time will pass before we can hope to enjoy that security & liberty we formerly enjoyed.

In all this time, I have as regards trade, kept myself quiet, more anxious to keep what I had in hand than to gain more, and have been more successful in getting in our money than I had dared to hope for. Still, however, we have large sums out that it will require much time & patience to collect. I have at times thought very seriously of leaving this. I have, however, on mature reflection, found it a more serious step than I was aware of. Such a step would naturally cause me much expense, and if after all I should be unsuccessful in a new establishment, I should then find myself where I was twelve years ago. If on the contrary, I can remain here in any kind of tolerable quiet & security, I can get along well enough. All the Brothers & Sisters of my wife have left this, still she has rather discouraged me from following them, & I trust yet that her impression that all will yet end well may be found right. If one half of the stories published in the European newspapers should find their way to the United States, you must have thought us all killed long ago...

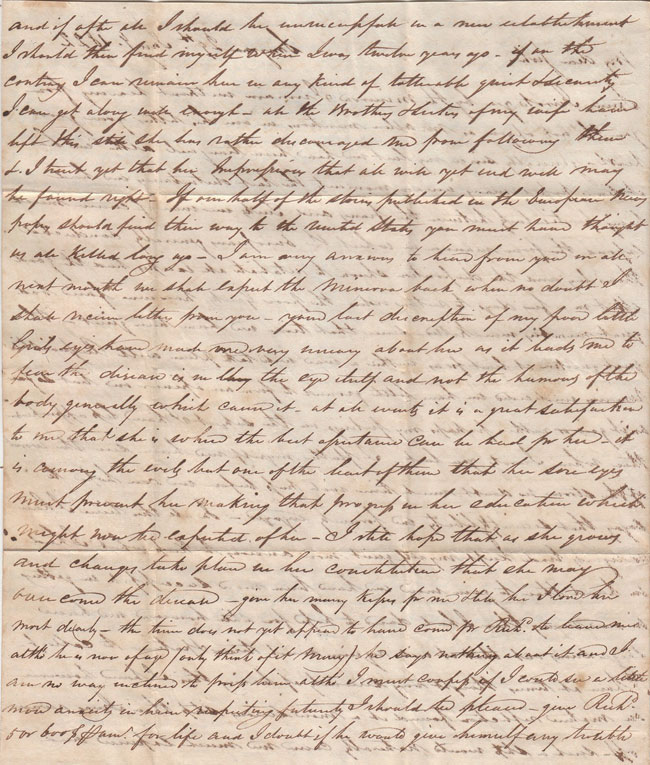

Your last description of my poor little girl’s eyes [his daughter Anne, who he left in the care of his mother & sister when he left for Turkey] has made me very uneasy about her, as it leads me to fear the disease is in the eye itself and not the humours of the body generally which cause it. At all events, it is a great satisfaction to me that she is where the best assistance can be had for her. It is among the evils, but one of the least of them, that her sore eyes must prevent her making that progress in her education which might now be expected of her. I still hope that as she grows, and changes take place in her constitution, that she may overcome the disease. Give her many kisses for me, & tell her I love her most dearly.

The time does not yet appear to have come for Richard [his son, who lives with him in Turkey] to leave me, altho’ he is now of age (only think of it, Mary). He says nothing about it, and I am no way inclined to press him, altho’ I must confess if I could see a little more anxiety in him respecting futurity, I should be pleased. Give Richard 5 or $600 per annum for life, and I doubt if he would give himself any trouble to gain more. I expect no change will take place in him until it is brought about by some female. With his sensibility, it is impossible he can go thro’ this world without coming under that influence.

Holmes [another son living with him] is now beginning to be a man, and I confidently hope will not only be a very amicable one, but will have every disposition & qualification to push his way thro’ this world. David [another son living with him] is yet quite a boy, altho' he is a very big one, little opinion can yet be formed of his character. So far it is not one likely to make him many friends. Where in the name of goodness he picked up all the pride he has got, I know not. We get on tolerably well, as he is perfectly obedient, but I plainly see that nothing short of my authority would make him so.

My little Edward [a son born to him from his second marriage, to a Greek woman in Smyrna] grows finely, & ‘is a pretty boy, just like his father’. That is all I can yet tell you of him....Helen [his Greek wife, married in Smyrna in 1820] is in good health, and I can now tell you, without, I believe, any offence to the modesty of an American lady, that she is again in the ‘family way’. If we are to pass such a summer as the last, sometimes in our house, and others aboard ship, I had just as leave today, to say the least of it, that she was not in such a way...

This year has been a very bad one for me in trade, as my expenses have been unavoidably greater than usual. A good sum, however, has gone in such a way as I have always been told will hereafter be paid with good interest. My losses at last must be very considerable. Take the thing in the best possible light, the gains have been very small. Still, I have experienced a greater degree of happiness at my fire side than I have felt for a long time. I even being to doubt whether prosperity is not rather inimacable to happiness than otherwise. After all, why should a man torment himself about tomorrow who is to die this night. My means are still equal to the acquirement of all things necessary or useful to me. My children will not have the opportunity of spending as much money as they might have had under a different state of affairs, & certainly there is no harm in that. So then, all things considered - patience...

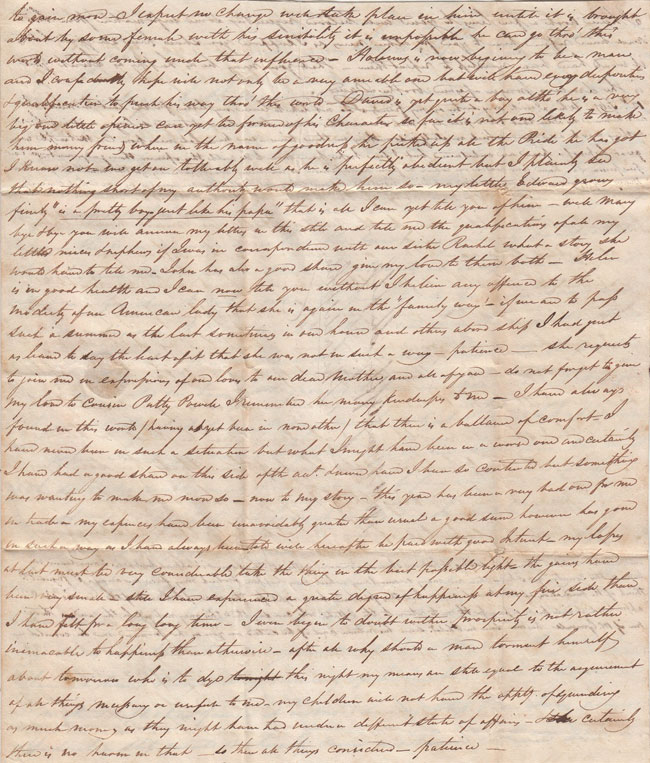

12th Feb’y. When I write my Sister or my friends, I do not like to leave my letters for the last moment. I had, however, no idea that the vessel by which I send this would have been detained so long. As it is, I have nothing new to add, and which in itself is something in these times. We have late news from Constantinople, where great hopes of a peace are entertained, but I fear hopes have more to do with this opinion than judgement. In fact, few persons can have any reason on which to form an opinion, so we must wait patiently for the result. You know, Mary, my opinions that our actions, not being regulated by our wills, but rather by circumstances over which generally we have no control. There is no saying what we shall do tomorrow, altho’ at this moment it appears probable I may leave my bones in this country, yet I know there are many circumstances which may happen & which may force me away. I frequently think of the predictions of Mr. Crouch, and which thus far have been right. For the accomplishment of the remainder, I apprehend it will be necesssary for me to return to the U. States. Who can say that this may not yet be the case...”

|

|

|

|

|