Examples of newspaper articles covering British soldiers in the service of the Ottoman Empire

|

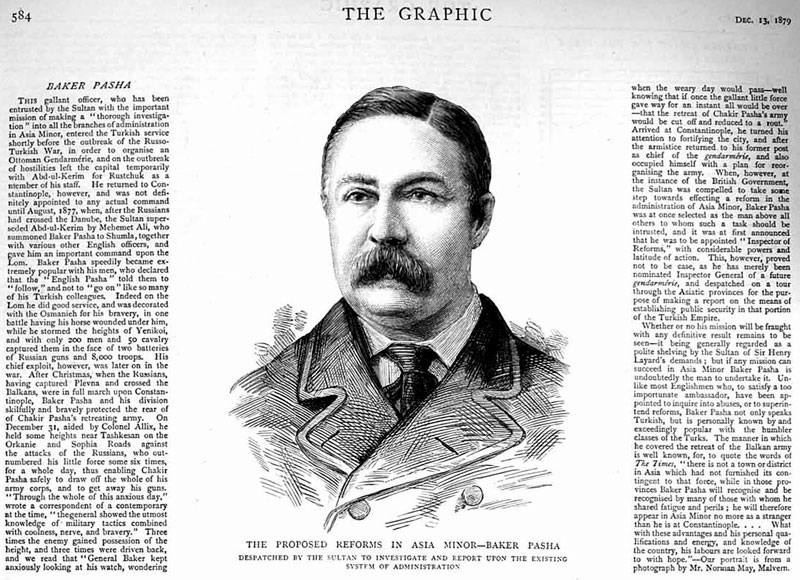

A cartoon depiction of Lt-Gen. Valentine Baker Pasha who entered the army 1848, served abroad including the Crimea.

|

|

|

Baker, Valentine [called Baker Pasha] (1827–1887), army officer, was born on 1 April 1827 at Enfield, the third son of Samuel Baker (d. 1862), later of Lypiatt Park, Stroud, Gloucestershire, and his first wife, Mary, daughter of Thomas Dobson of Enfield. The family’s wealth had been established by the first Valentine Baker, a privateer during the American War of Independence and owner of sugar plantations in Jamaica and Mauritius. Samuel Baker inherited the plantations and was also a successful businessman, shipowner, director of the Great Western Railway, and chairman of the Gloucester Bank. He was unusual in his regard for education, and his close-knit family of seven surviving children attended local schools, including the College School, Gloucester, were tutored at home, and studied abroad.

Early military career

Baker was intended for the army, with a commission purchased in the 10th hussars. He went first in 1848 to Ceylon, where his eldest brother, the explorer Samuel White Baker (1821–1893), had purchased land, intending, with family and settlers, to create an English colony, at the same time indulging the brothers’ passion for big-game hunting. In 1848 Baker joined, as ensign, the Ceylon rifles, and in April 1851 went to India to join the 10th hussars.

In 1852 Baker transferred to the 12th lancers in order to participate in the Basuto War in South Africa, distinguishing himself by his gallantry in action at the Berea in December 1852. Promoted lieutenant without purchase in July 1853, he served in India. He was still with the 12th lancers when the regiment was sent to the Crimea, reaching Balaklava in April 1855, and was present at the battle of Chernaya and the fall of Sevastopol. His active service showed him faults of the British cavalry which he later tried to reform.

In 1856, when the 12th lancers returned to India, Baker rejoined the 10th hussars, an expensive regiment with the highest social position in the cavalry of the line, as captain (by purchase). He obtained his majority (by purchase) in 1859 and, taking command of the regiment in 1860, remained as its colonel (by purchase, full colonel 1865) until 1873. As a peace-time soldier Baker established his reputation as a brilliant cavalry officer, a perfectionist devoted to his troops, and a theorist. In 1858 he produced The British Cavalry, an extension of Lewis Nolan’s work: his practical recommendations on equipment, uniform, and stud farms were later in part adopted. In 1860 he wrote Our National Defences, expounding his conviction that France’s aggressive preparations were directed at Britain and proposing defence changes including linked battalions and a ‘national guard’. In 1869 he set out proposals in Army Reform, recommending changes in regimental administration, and submitted comments to the royal commission on military education, condemning the ‘cramming’ system. As background to his studies he travelled in Europe, inspecting military establishments, and was present as an observer during the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian wars. In his writing Baker expressed himself clearly and incisively, ‘always jolting the establishment, questioning the status quo or challenging the fashionable’ (Anglesey, 3.117).

As colonel of the 10th hussars Baker made his regiment smart, efficient, and dynamic, and won the devotion of his officers and men. He was prepared to make changes and experiment, and he had the gift of communicating his ideas and enthusiasms. He was the first to experiment with railway transport of troops (July 1860), and his regiment was among the first to learn the new system of signalling.

Friendship with the prince of Wales, and marriage

In 1863, when the prince of Wales (later Edward VII) became colonel-in-chief, Baker had additional support for his innovations, and the relationship between the two developed into friendship. From 1863 to 1867, while the 10th hussars were stationed in Ireland, Baker was able, at relative distance from the War Office, to work on various reforms, including his new ‘non-pivot drill’. The 10th was used in support of the civil power and against the Fenians. During the 1867 Fenian uprising Baker commanded the Thurles flying column, for which he was commended by the commander-in-chief, Ireland.

Back in England regimental highlights were ceremonial occasions, with the prince and the colonel leading the parades and the regiment presenting its disciplined best and its superior horses (Baker’s policy was to invest in blood horses with staying power). When the 10th hussars were posted to India at the end of 1872, Baker resigned.

The years of his command were also successful for Baker personally. On 13 December 1865 he married Fanny (d. 1885), only child of Frank Wormald of Potterton Hall, Aberford, Yorkshire; they had two daughters. His friendship with the prince of Wales led to membership of the Marlborough Club, London, a social centre for the prince’s friends. He became a friend of Frederick Burnaby (1842–1885) of the Royal Horse Guards, and won the approval of the duke of Cambridge, the commander-in-chief of the British army.

Baker in central Asia

In April 1873, while awaiting a new appointment, Baker set out with two military companions on a journey to northern Persia, Turkestan, and the borders of Afghanistan. It was a private expedition, a grand hunting party, but also an exploratory venture prompted by Russian advances through central Asia.

Baker kept a daily journal in which, as well as sporting descriptions, he reported on political discussions and military possibilities. The journey was full of incident and endurance: Baker fell seriously ill, and suffered frustration because his expedition lacked official approval. In his detailed account, published in 1876 as Clouds in the East, he provided an evaluation of Russian advances towards India, criticized British foreign policy, urged military preparedness and a ‘bolder policy’ against Russia in Asia, and proposed a nine-point plan of action (the basis of his lecture to the Royal United Service Institution in May 1874).

Baker and Miss Dickinson: imprisoned and cashiered

In September 1874 Valentine Baker was appointed assistant quartermaster-general at Aldershot, with his first major responsibility the organization of a grand army review to take place in August 1875. It was a period of consolidation in his career: he was expected to be an established general by the 1880s. Instead an incident took place on a train and Baker’s career in the British army was ended.

On 17 June 1875 Baker travelled to London with an appointment to dine with the duke of Cambridge. In a first-class compartment he talked with a young lady, Miss Dickinson, the sister of a Royal Engineers officer, and, it was alleged, tried to rape her. He was arrested; evidence against him was given by two gentlemen in the next compartment in addition to the detailed account of Miss Dickinson. There was public outcry against him, much moral indignation, and crowds gathered at the trial, which began on 30 July at Croydon assizes. The judge, Mr Justice Brett, spoke of the incident as ‘a sudden outbreak of wickedness’ and hoped that at some future time Baker might redeem himself ‘by some brilliant service’ (The Times, 3 Aug 1875, 10). On 2 August he was acquitted of attempted rape, convicted on the lesser charge of indecent assault, fined £500, and sentenced to a year’s imprisonment.

Baker was cashiered, ‘Her Majesty having no further occasion for his services’ (Annual Register, 1875, 55). This was the queen’s decision. She thought his brother Samuel Baker unprincipled, and was convinced that Valentine was like him, and a disgrace to the British army. Baker’s wife, family, and friends, including the prince of Wales, stood by him. They, and his regiment, and most of the army believed, and continued to believe, that there had been mitigating circumstances, evidence not revealed, and that it had not been a fair trial.

The Eastern question

On release from prison Baker left for Constantinople in September 1876, taking up an appointment, through the intervention of the prince, with the Turkish government. He was to organize a new system of civil gendarmerie, and was to advise the Turkish army on strengthening the fortifications around Constantinople.

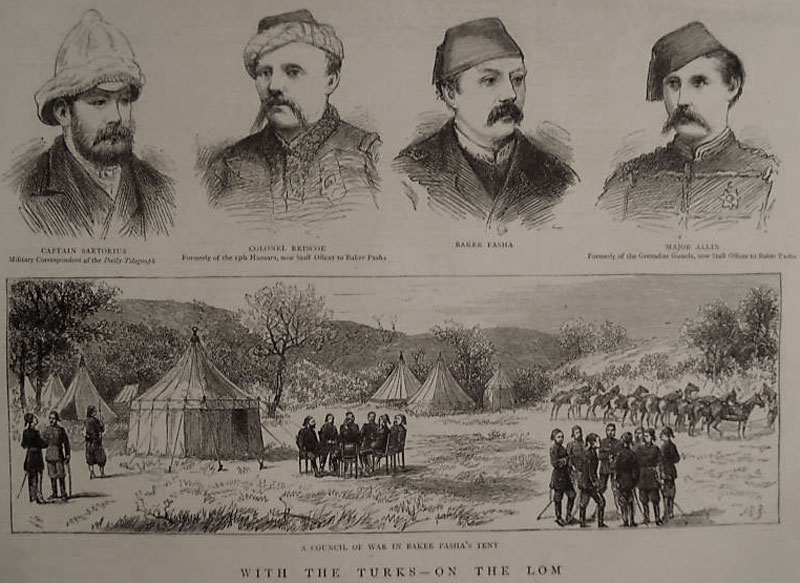

War between Russia and Turkey broke out in April 1877, and in August Baker took up a command as general available for special services (henceforth he was known as Baker Pasha) and set out for the front at Shumla in Bulgaria. With him at his camp were his gendarmerie officers and an assortment of doctors, newspaper correspondents, MPs, and army officers come to observe the war. Among these was Herbert Kitchener, who was to become a friend and champion of Baker. Also there arrived unexpectedly Fred Burnaby.

The Russian armies crossed the Danube, but the Turkish armies stopped their advance. It was not until the fortress of Plevna fell on 10 December 1877 that the Russians began to cross the mountains. Baker commanded the centre division of the army at Kamarli, and, recognizing the importance of the pass of Tashkesan, he made an offer to the Turkish commander, guaranteeing that he would hold it to the last. This his division did, in a battle that lasted more than ten hours against vastly superior Russian forces. No reinforcements came, and the losses were severe. Just before nightfall another Russian attack was repulsed, and Baker’s troops knew the day was won. That rear-guard action allowed the Turkish army to make an organized retreat: there was a telegram from the sultan and Baker was promoted lieutenant-general.

Baker, with Burnaby as his companion and support, joined the main body of the army in its retreat across Bulgaria. He was consulted by the Turkish army about defences for Constantinople, and asked to take on the command of the existing fortifications. Before he could take up the new post, the Turkish government had yielded to Russian demands in the treaty of San Stefano, and Baker, disgusted at the humiliation that would now be served upon the army—and his opinion of and love for his Turkish soldiers were great—asked for leave of absence.

Baker was acclaimed by the British public as a hero. The newspapers were enthusiastic in describing his military achievements, and Tashkesan was applauded as one of the most brilliant rear-guard actions of all time. He was re-elected to the Marlborough Club in March 1878 (and in 1881 to the Army and Navy Club). His War in Bulgaria (2 vols., 1879) revealed the enthusiastic soldier and the disappointed general, and his disillusionment with the Turkish high command; but it argued for continued support of Turkey against Russian advances on India. From the war he drew military lessons for Britain. Like others, he emphasized the lethality of rifle firepower and the necessity of entrenching, loose formations, and flank attacks, but claimed that cavalry could still be effective in battle.

Baker stayed on in Turkey with a new army position. His standing was high with the Turkish government and he was in favour with the sultan. His major tasks were to carry out army reforms; by 1879 his plans were sufficiently advanced for him to include chapters on the reorganization of the Turkish army in War in Bulgaria.

Organizing the Egyptian army

In 1882 came an invitation from the khedive to organize and command a new Egyptian army. As a consequence of the British occupation of Egypt, Lord Dufferin, ambassador at Constantinople, had been authorized to draw up plans for a reformed Egyptian administration. High priority was given to a new army under the command of a British general with British officers in all supporting ranks.

Baker, consulting Dufferin, was assured that his appointment would be supported by the British cabinet. By October 1882 he was in Cairo with his plans for the army and his list of British officers willing to serve under him approved by the khedive. Two months later he was relieved of his post: the queen would not accept his appointment. The cabinet denied that it had given its approval, claiming that it was not possible for British officers to serve under a general who was not himself a serving British general. Baker was offered a command, as inspector-general, of a new gendarmerie and police force, a post to which the queen had no objections. Baker accepted, handing over his army plans and list to Sir Evelyn Wood.

In the new force Baker planned to use semi-military mounted troops in rural Egypt and civilian police in the towns; he was able to choose as officers a number of those who had served with him in Turkey. Administratively, the gendarmerie became the responsibility of the ministry of the interior. The calibre of the recruited men was low, but in mid-1883, when cholera swept Cairo, the new service showed its value in manning the cordons. Administrative difficulties followed with the British cabinet’s appointment of Clifford Lloyd to undertake reforms in the ministry. Lloyd, with little knowledge of Egypt, took exception to Baker’s gendarmerie, and by the end of 1883 had decided upon its abolition.

The British gave no support to the Egyptian government in its actions in the Sudan, but interfered. In February 1883 the khedive, on Baker’s recommendation, appointed General Williams Hicks Pasha to retrain the army and overcome the Mahdist rebels. Hicks was assured of the support of a Sudan committee, with Baker as its executive officer. But the British objected to the committee and obstructed communications between Baker (ministry of interior) and Hicks (ministry of war). Hicks was not informed of the administrative changes, and became increasingly isolated. In November 1883 his army was annihilated by Mahdist forces and another Egyptian army was defeated. Military action was required immediately to relieve garrisons in eastern Sudan. The British government refused to allow the new Egyptian army to go to the Sudan (because its officers were also serving British officers), nor would it send the British army of occupation. The only force available was the gendarmerie, and the khedive made a personal appeal to Baker. By December 1883 the gendarmerie, unwilling, ill-prepared, undisciplined, was on its way.

At Suakin on the Red Sea, Baker tried to carry out the contradictory instructions received from the khedive and Sir Evelyn Baring, the British consul-general—to pacify the country, but not to embark on military action—while training his troops. The promised support from Cairo—ships, supplies, more troops—was delayed. The Sudanese reinforcements arrived without their promised leader, Zobehr Pasha, because of British objections to his background as a slave dealer. When the telegraph was installed, an official message arrived that the Egyptian government, under pressure from the British, was abandoning all activities in the Sudan. Baker and his force were left isolated. On 4 February 1884, with nearly 4000 men, he marched out of Trinkitat to cross the desert to relieve the garrison at Tokar: accompanying him was his friend Burnaby, who had arrived in response to a telegram from Baker’s wife. The Mahdist rebels were waiting, Baker’s force was attacked and panicked: more than 2300 men were killed at al-Teb, many speared in the back. Among those who died were gendarmerie officers who had been with Baker in Bulgaria.

Rear-Admiral Sir William Hewett, stationed with his five ships in Suakin harbour, took over. The remnants of Baker’s force were shipped back to Cairo, the officers to find that their posts had been abolished. There was consternation in London, and on 14 February the British government agreed to immediate military action. Major-General Sir Gerald Graham was in Suakin by 22 February, commanding a British force which included a troopship with men of the 10th hussars (who welcomed Baker enthusiastically). At the second battle of al-Teb on 29 February the Mahdists were defeated. Baker, acting as chief intelligence officer, was severely wounded in the face, and received special commendation in Graham’s dispatches. Baker’s friends and the public appealed once more for his reinstatement: again the queen refused.

Lloyd resigned in May 1884, his reforms were set aside, and Baker began rebuilding his force. Still believing in the need for semi-military troops, he concentrated on the gendarmerie, allowing the traditional policing system to remain. In January 1885 Baker, sharing in the public grief over the death of Gordon at Khartoum, also suffered personal losses. Burnaby was killed at Abu Klea. Baker’s elder daughter, Hermione, died, aged eighteen, later that month, and his wife, Fanny, in February, both from typhoid: their deaths ‘seemed to have crushed his spirit’ (Annual Register, 1887, 161). He stayed on in Cairo, continuing as inspector-general of the gendarmerie.

Death and reputation

In June 1887, the year of her jubilee, the queen wrote to the prince of Wales proposing that Baker be reinstated. There was no immediate announcement, instead administrative delays. Following an attack of fever, on 17 November 1887 Baker died of a heart attack aboard the steam-launch Vigilant on the Sweetwater Canal at Tell al-Kebir. A telegram from the War Office gave instructions from the duke of Cambridge that he was to be buried with full military honours. A union flag was draped on his coffin and on 19 November the procession set out for the English cemetery in Cairo from the house of Sir Frederick Stephenson, commander of the British army in Egypt, who spoke of Baker as the bravest soldier England had ever had. Sir Evelyn Baring wrote to the prime minister about Baker with warmth and understanding, and also to Samuel Baker of his close friendship with Baker; Lord Salisbury, in responding to Baring, was equally generous.

The Times obituary commented, ‘his career … might have been among the most brilliant in our service’; and wrote of ‘the error which deprived his country of his services’, and ‘the splendid atonement which he sought to make’ (The Times, 18 Nov 1887, 7). A memorial plaque in honour of ‘Lieutenant General Valentine Baker Pasha’ was erected in the Anglican cathedral, Cairo, by the British army.

Baker was strongly built, high-coloured, and walrus-moustached, with piercing dark eyes. He was an exceptional soldier, ‘one of the most remarkable cavalrymen of the age’ (Anglesey, 3.116), and he had once been a member of the social circle around the prince of Wales. But he was essentially a quiet, serious man, courageous in action and in word, a companion to his fellow officers, generous to his men, considerate to those of different race and religion; private, more interested in family than society, he was without bravado. He was liked and held in high respect by his peers, by Sir Evelyn Baring, Sir Frederick Stephenson, Admiral Hewett, and General Graham. He also enjoyed the continuing loyal regard of the officers and men of the 10th hussars and the long-standing friendship of their colonel-in-chief, the prince of Wales. If Baker had been responsible for the incident on the train, and many believed otherwise, it had been an aberration.

Dorothy Anderson - Oxford National Biography

Early military career

Baker was intended for the army, with a commission purchased in the 10th hussars. He went first in 1848 to Ceylon, where his eldest brother, the explorer Samuel White Baker (1821–1893), had purchased land, intending, with family and settlers, to create an English colony, at the same time indulging the brothers’ passion for big-game hunting. In 1848 Baker joined, as ensign, the Ceylon rifles, and in April 1851 went to India to join the 10th hussars.

In 1852 Baker transferred to the 12th lancers in order to participate in the Basuto War in South Africa, distinguishing himself by his gallantry in action at the Berea in December 1852. Promoted lieutenant without purchase in July 1853, he served in India. He was still with the 12th lancers when the regiment was sent to the Crimea, reaching Balaklava in April 1855, and was present at the battle of Chernaya and the fall of Sevastopol. His active service showed him faults of the British cavalry which he later tried to reform.

In 1856, when the 12th lancers returned to India, Baker rejoined the 10th hussars, an expensive regiment with the highest social position in the cavalry of the line, as captain (by purchase). He obtained his majority (by purchase) in 1859 and, taking command of the regiment in 1860, remained as its colonel (by purchase, full colonel 1865) until 1873. As a peace-time soldier Baker established his reputation as a brilliant cavalry officer, a perfectionist devoted to his troops, and a theorist. In 1858 he produced The British Cavalry, an extension of Lewis Nolan’s work: his practical recommendations on equipment, uniform, and stud farms were later in part adopted. In 1860 he wrote Our National Defences, expounding his conviction that France’s aggressive preparations were directed at Britain and proposing defence changes including linked battalions and a ‘national guard’. In 1869 he set out proposals in Army Reform, recommending changes in regimental administration, and submitted comments to the royal commission on military education, condemning the ‘cramming’ system. As background to his studies he travelled in Europe, inspecting military establishments, and was present as an observer during the Austro-Prussian and Franco-Prussian wars. In his writing Baker expressed himself clearly and incisively, ‘always jolting the establishment, questioning the status quo or challenging the fashionable’ (Anglesey, 3.117).

As colonel of the 10th hussars Baker made his regiment smart, efficient, and dynamic, and won the devotion of his officers and men. He was prepared to make changes and experiment, and he had the gift of communicating his ideas and enthusiasms. He was the first to experiment with railway transport of troops (July 1860), and his regiment was among the first to learn the new system of signalling.

Friendship with the prince of Wales, and marriage

In 1863, when the prince of Wales (later Edward VII) became colonel-in-chief, Baker had additional support for his innovations, and the relationship between the two developed into friendship. From 1863 to 1867, while the 10th hussars were stationed in Ireland, Baker was able, at relative distance from the War Office, to work on various reforms, including his new ‘non-pivot drill’. The 10th was used in support of the civil power and against the Fenians. During the 1867 Fenian uprising Baker commanded the Thurles flying column, for which he was commended by the commander-in-chief, Ireland.

Back in England regimental highlights were ceremonial occasions, with the prince and the colonel leading the parades and the regiment presenting its disciplined best and its superior horses (Baker’s policy was to invest in blood horses with staying power). When the 10th hussars were posted to India at the end of 1872, Baker resigned.

The years of his command were also successful for Baker personally. On 13 December 1865 he married Fanny (d. 1885), only child of Frank Wormald of Potterton Hall, Aberford, Yorkshire; they had two daughters. His friendship with the prince of Wales led to membership of the Marlborough Club, London, a social centre for the prince’s friends. He became a friend of Frederick Burnaby (1842–1885) of the Royal Horse Guards, and won the approval of the duke of Cambridge, the commander-in-chief of the British army.

Baker in central Asia

In April 1873, while awaiting a new appointment, Baker set out with two military companions on a journey to northern Persia, Turkestan, and the borders of Afghanistan. It was a private expedition, a grand hunting party, but also an exploratory venture prompted by Russian advances through central Asia.

Baker kept a daily journal in which, as well as sporting descriptions, he reported on political discussions and military possibilities. The journey was full of incident and endurance: Baker fell seriously ill, and suffered frustration because his expedition lacked official approval. In his detailed account, published in 1876 as Clouds in the East, he provided an evaluation of Russian advances towards India, criticized British foreign policy, urged military preparedness and a ‘bolder policy’ against Russia in Asia, and proposed a nine-point plan of action (the basis of his lecture to the Royal United Service Institution in May 1874).

Baker and Miss Dickinson: imprisoned and cashiered

In September 1874 Valentine Baker was appointed assistant quartermaster-general at Aldershot, with his first major responsibility the organization of a grand army review to take place in August 1875. It was a period of consolidation in his career: he was expected to be an established general by the 1880s. Instead an incident took place on a train and Baker’s career in the British army was ended.

On 17 June 1875 Baker travelled to London with an appointment to dine with the duke of Cambridge. In a first-class compartment he talked with a young lady, Miss Dickinson, the sister of a Royal Engineers officer, and, it was alleged, tried to rape her. He was arrested; evidence against him was given by two gentlemen in the next compartment in addition to the detailed account of Miss Dickinson. There was public outcry against him, much moral indignation, and crowds gathered at the trial, which began on 30 July at Croydon assizes. The judge, Mr Justice Brett, spoke of the incident as ‘a sudden outbreak of wickedness’ and hoped that at some future time Baker might redeem himself ‘by some brilliant service’ (The Times, 3 Aug 1875, 10). On 2 August he was acquitted of attempted rape, convicted on the lesser charge of indecent assault, fined £500, and sentenced to a year’s imprisonment.

Baker was cashiered, ‘Her Majesty having no further occasion for his services’ (Annual Register, 1875, 55). This was the queen’s decision. She thought his brother Samuel Baker unprincipled, and was convinced that Valentine was like him, and a disgrace to the British army. Baker’s wife, family, and friends, including the prince of Wales, stood by him. They, and his regiment, and most of the army believed, and continued to believe, that there had been mitigating circumstances, evidence not revealed, and that it had not been a fair trial.

The Eastern question

On release from prison Baker left for Constantinople in September 1876, taking up an appointment, through the intervention of the prince, with the Turkish government. He was to organize a new system of civil gendarmerie, and was to advise the Turkish army on strengthening the fortifications around Constantinople.

War between Russia and Turkey broke out in April 1877, and in August Baker took up a command as general available for special services (henceforth he was known as Baker Pasha) and set out for the front at Shumla in Bulgaria. With him at his camp were his gendarmerie officers and an assortment of doctors, newspaper correspondents, MPs, and army officers come to observe the war. Among these was Herbert Kitchener, who was to become a friend and champion of Baker. Also there arrived unexpectedly Fred Burnaby.

The Russian armies crossed the Danube, but the Turkish armies stopped their advance. It was not until the fortress of Plevna fell on 10 December 1877 that the Russians began to cross the mountains. Baker commanded the centre division of the army at Kamarli, and, recognizing the importance of the pass of Tashkesan, he made an offer to the Turkish commander, guaranteeing that he would hold it to the last. This his division did, in a battle that lasted more than ten hours against vastly superior Russian forces. No reinforcements came, and the losses were severe. Just before nightfall another Russian attack was repulsed, and Baker’s troops knew the day was won. That rear-guard action allowed the Turkish army to make an organized retreat: there was a telegram from the sultan and Baker was promoted lieutenant-general.

Baker, with Burnaby as his companion and support, joined the main body of the army in its retreat across Bulgaria. He was consulted by the Turkish army about defences for Constantinople, and asked to take on the command of the existing fortifications. Before he could take up the new post, the Turkish government had yielded to Russian demands in the treaty of San Stefano, and Baker, disgusted at the humiliation that would now be served upon the army—and his opinion of and love for his Turkish soldiers were great—asked for leave of absence.

Baker was acclaimed by the British public as a hero. The newspapers were enthusiastic in describing his military achievements, and Tashkesan was applauded as one of the most brilliant rear-guard actions of all time. He was re-elected to the Marlborough Club in March 1878 (and in 1881 to the Army and Navy Club). His War in Bulgaria (2 vols., 1879) revealed the enthusiastic soldier and the disappointed general, and his disillusionment with the Turkish high command; but it argued for continued support of Turkey against Russian advances on India. From the war he drew military lessons for Britain. Like others, he emphasized the lethality of rifle firepower and the necessity of entrenching, loose formations, and flank attacks, but claimed that cavalry could still be effective in battle.

Baker stayed on in Turkey with a new army position. His standing was high with the Turkish government and he was in favour with the sultan. His major tasks were to carry out army reforms; by 1879 his plans were sufficiently advanced for him to include chapters on the reorganization of the Turkish army in War in Bulgaria.

Organizing the Egyptian army

In 1882 came an invitation from the khedive to organize and command a new Egyptian army. As a consequence of the British occupation of Egypt, Lord Dufferin, ambassador at Constantinople, had been authorized to draw up plans for a reformed Egyptian administration. High priority was given to a new army under the command of a British general with British officers in all supporting ranks.

Baker, consulting Dufferin, was assured that his appointment would be supported by the British cabinet. By October 1882 he was in Cairo with his plans for the army and his list of British officers willing to serve under him approved by the khedive. Two months later he was relieved of his post: the queen would not accept his appointment. The cabinet denied that it had given its approval, claiming that it was not possible for British officers to serve under a general who was not himself a serving British general. Baker was offered a command, as inspector-general, of a new gendarmerie and police force, a post to which the queen had no objections. Baker accepted, handing over his army plans and list to Sir Evelyn Wood.

In the new force Baker planned to use semi-military mounted troops in rural Egypt and civilian police in the towns; he was able to choose as officers a number of those who had served with him in Turkey. Administratively, the gendarmerie became the responsibility of the ministry of the interior. The calibre of the recruited men was low, but in mid-1883, when cholera swept Cairo, the new service showed its value in manning the cordons. Administrative difficulties followed with the British cabinet’s appointment of Clifford Lloyd to undertake reforms in the ministry. Lloyd, with little knowledge of Egypt, took exception to Baker’s gendarmerie, and by the end of 1883 had decided upon its abolition.

The British gave no support to the Egyptian government in its actions in the Sudan, but interfered. In February 1883 the khedive, on Baker’s recommendation, appointed General Williams Hicks Pasha to retrain the army and overcome the Mahdist rebels. Hicks was assured of the support of a Sudan committee, with Baker as its executive officer. But the British objected to the committee and obstructed communications between Baker (ministry of interior) and Hicks (ministry of war). Hicks was not informed of the administrative changes, and became increasingly isolated. In November 1883 his army was annihilated by Mahdist forces and another Egyptian army was defeated. Military action was required immediately to relieve garrisons in eastern Sudan. The British government refused to allow the new Egyptian army to go to the Sudan (because its officers were also serving British officers), nor would it send the British army of occupation. The only force available was the gendarmerie, and the khedive made a personal appeal to Baker. By December 1883 the gendarmerie, unwilling, ill-prepared, undisciplined, was on its way.

At Suakin on the Red Sea, Baker tried to carry out the contradictory instructions received from the khedive and Sir Evelyn Baring, the British consul-general—to pacify the country, but not to embark on military action—while training his troops. The promised support from Cairo—ships, supplies, more troops—was delayed. The Sudanese reinforcements arrived without their promised leader, Zobehr Pasha, because of British objections to his background as a slave dealer. When the telegraph was installed, an official message arrived that the Egyptian government, under pressure from the British, was abandoning all activities in the Sudan. Baker and his force were left isolated. On 4 February 1884, with nearly 4000 men, he marched out of Trinkitat to cross the desert to relieve the garrison at Tokar: accompanying him was his friend Burnaby, who had arrived in response to a telegram from Baker’s wife. The Mahdist rebels were waiting, Baker’s force was attacked and panicked: more than 2300 men were killed at al-Teb, many speared in the back. Among those who died were gendarmerie officers who had been with Baker in Bulgaria.

Rear-Admiral Sir William Hewett, stationed with his five ships in Suakin harbour, took over. The remnants of Baker’s force were shipped back to Cairo, the officers to find that their posts had been abolished. There was consternation in London, and on 14 February the British government agreed to immediate military action. Major-General Sir Gerald Graham was in Suakin by 22 February, commanding a British force which included a troopship with men of the 10th hussars (who welcomed Baker enthusiastically). At the second battle of al-Teb on 29 February the Mahdists were defeated. Baker, acting as chief intelligence officer, was severely wounded in the face, and received special commendation in Graham’s dispatches. Baker’s friends and the public appealed once more for his reinstatement: again the queen refused.

Lloyd resigned in May 1884, his reforms were set aside, and Baker began rebuilding his force. Still believing in the need for semi-military troops, he concentrated on the gendarmerie, allowing the traditional policing system to remain. In January 1885 Baker, sharing in the public grief over the death of Gordon at Khartoum, also suffered personal losses. Burnaby was killed at Abu Klea. Baker’s elder daughter, Hermione, died, aged eighteen, later that month, and his wife, Fanny, in February, both from typhoid: their deaths ‘seemed to have crushed his spirit’ (Annual Register, 1887, 161). He stayed on in Cairo, continuing as inspector-general of the gendarmerie.

Death and reputation

In June 1887, the year of her jubilee, the queen wrote to the prince of Wales proposing that Baker be reinstated. There was no immediate announcement, instead administrative delays. Following an attack of fever, on 17 November 1887 Baker died of a heart attack aboard the steam-launch Vigilant on the Sweetwater Canal at Tell al-Kebir. A telegram from the War Office gave instructions from the duke of Cambridge that he was to be buried with full military honours. A union flag was draped on his coffin and on 19 November the procession set out for the English cemetery in Cairo from the house of Sir Frederick Stephenson, commander of the British army in Egypt, who spoke of Baker as the bravest soldier England had ever had. Sir Evelyn Baring wrote to the prime minister about Baker with warmth and understanding, and also to Samuel Baker of his close friendship with Baker; Lord Salisbury, in responding to Baring, was equally generous.

The Times obituary commented, ‘his career … might have been among the most brilliant in our service’; and wrote of ‘the error which deprived his country of his services’, and ‘the splendid atonement which he sought to make’ (The Times, 18 Nov 1887, 7). A memorial plaque in honour of ‘Lieutenant General Valentine Baker Pasha’ was erected in the Anglican cathedral, Cairo, by the British army.

Baker was strongly built, high-coloured, and walrus-moustached, with piercing dark eyes. He was an exceptional soldier, ‘one of the most remarkable cavalrymen of the age’ (Anglesey, 3.116), and he had once been a member of the social circle around the prince of Wales. But he was essentially a quiet, serious man, courageous in action and in word, a companion to his fellow officers, generous to his men, considerate to those of different race and religion; private, more interested in family than society, he was without bravado. He was liked and held in high respect by his peers, by Sir Evelyn Baring, Sir Frederick Stephenson, Admiral Hewett, and General Graham. He also enjoyed the continuing loyal regard of the officers and men of the 10th hussars and the long-standing friendship of their colonel-in-chief, the prince of Wales. If Baker had been responsible for the incident on the train, and many believed otherwise, it had been an aberration.

Dorothy Anderson - Oxford National Biography

|

|

|

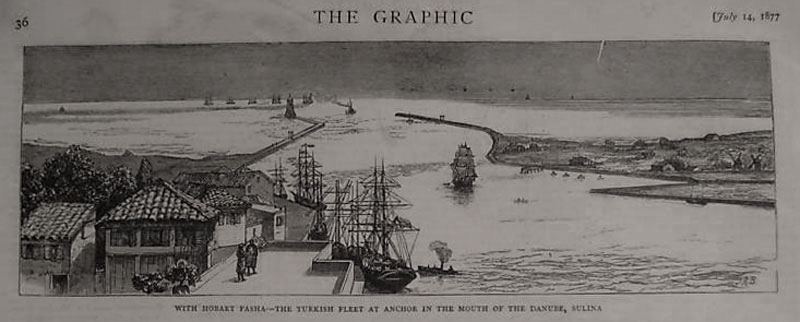

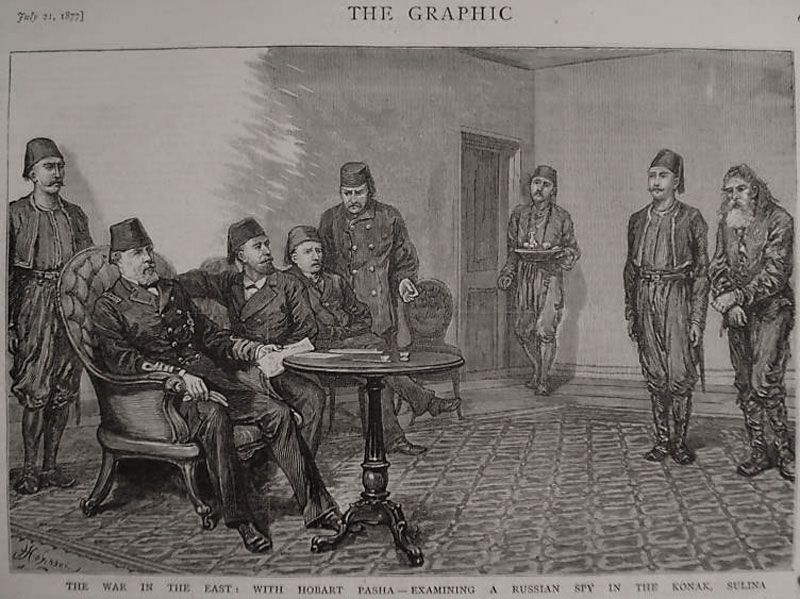

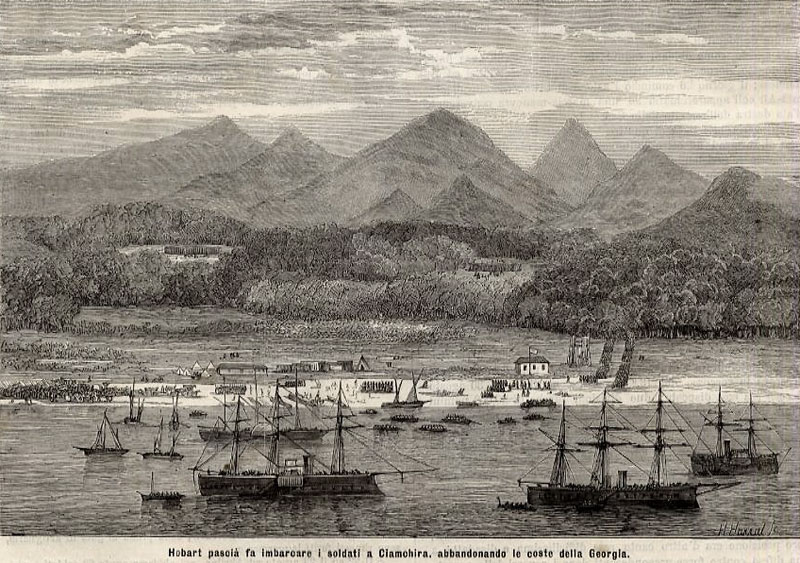

Hobart Pasha and the fleet departing the coast of Georgia, 1878.

|

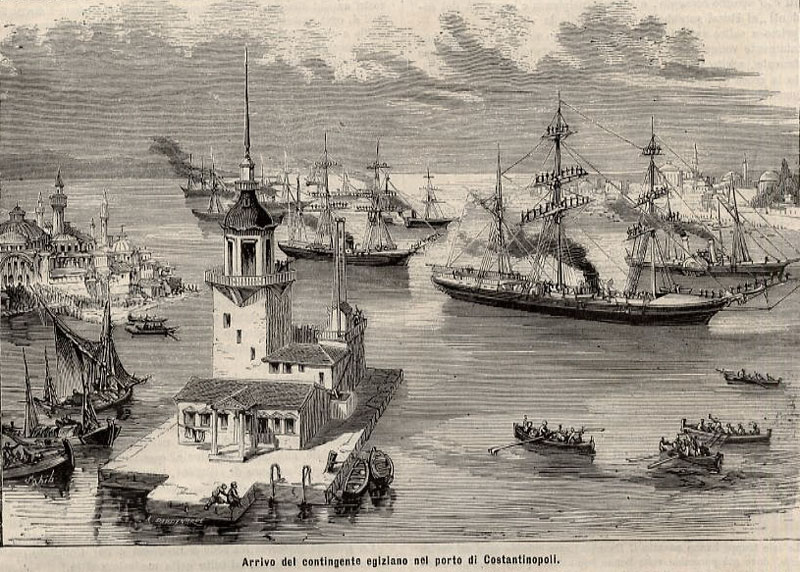

The fleet arriving in Constantinople, 1878.