Recollections of the Zacharie Family in Izmir 1956/1957 - Malcolm Hutton, 2013 |

|

Sadly there is only Lydia today who may be add a little to these memories of that period and of the Levantine families she knew. Everyone else, save Edda who has Alzheimer’s disease, who once lived at 21 Inkilap Sokak, Karşıyaka is no longer with us.

The following is drawn from my memoirs of those happy days.

1955, one year after being demobbed from the RAF.

Back into the same old routine, I began to question what I was doing, and where life was going. Commuting back and forth to the City, in what was more often than not, a packed train with standing room only, I was unable to open a book, never mind a paper. So I had a lot of time to mull things over. All the old stories about life down under resurfaced, and the unsettling process was well under way. When I found that I was even missing life in Aden, then I knew that I could never become a permanent fixture in the City. My colleagues at the Bank seemed happy enough with their slot in life. I just found it alarming, when I saw that their job satisfaction centred on the weekly balance. When this was achieved, they were in ‘Seventh Heaven’.

My social life was just about down to bedrock with what I thought was a disappointment, but was more likely a miscalculation of the situation. With morale at its lowest, I turned once more to pen and paper, and answered an ‘ad’ for a pen pal, that had caught my eye in one of the weekly newspapers. Only a name and address in Izmir was given. Until I got out my atlas, I must confess that it only conjured up a picture of a seaport town, somewhere in the Middle East. Perhaps it was a feeling of affinity with the area that made me pick it out. If the R.A.F. had given me a posting to any other Command, I wonder now, if I would ever had given that ‘ad’ of Lydia’s more than a second glance.

In the months that followed, correspondence between us became very regular and frequent. It wasn’t long before I knew that my next departure from the Motherland would be to Turkey. About the same time, the Bartholomew family, who had settled down well in their new home and country, repeated their invitation for me to go and stay with them in Melbourne.

Work was now little more than a daily chore, with all interest in what I was doing, about as low as it could get. I determined to break with my banking career, and return to the world of travel. It was just a question of how and when. I couldn’t do anything too quickly. Dad had taken a six-month contract with a company, which had sent him out to work in Jordan and I didn’t want to leave Mum alone at Christmas. Besides, his absence had forced me to do something at last about getting a driving licence. With long waiting lists, I had to wait until January for a test. Once I had my licence, I felt that there was nothing else to hold me. I can well remember the morning when I made the big decision. The outcome was to set me on a course that was to govern my future home and family.

I had walked all the way from Durley Avenue to Rayners Lane, on my way to the station, to catch the Underground to work. Weighing up all the pros and cons, I had just reached the shopping centre when I realised that all of the arguments in my head, would go on, until I made the break. There and then, I resolved to call Derek as soon as I got to the Bank, to find out what ships were leaving for Melbourne, and how best to fit in a stop in Turkey along the way.

When I learned that the “Oronsay” was leaving on the 29th February, and would call at a Greek port, I asked Derek to make some bookings for me, before I could change my mind. Anyone who has undertaken a one way trip, will know just how different are the sensations coursing through the mind and body. All the familiar thrill of planning and anticipation is there. But, an overlaying feeling almost verging on a dread of the unknown tempers any excitement.

In a world where the opposite hemisphere is only twenty-four hours away, it is perhaps difficult to understand that in the days when the Ocean Liner reigned supreme, the idea of voyaging so far, was still thought of by many people as a one way ticket to the end of the Earth. One was unlikely ever to be seen again. So on top of the inexorable nervousness that I was enduring, I had to allay the fears of elder members of the family. Added to all of this was the uncertainty of whatever might be in store for me in Turkey, not to mention the possibility of hazards in traversing Greece to join the “Oronsay”.

Few ships then, called in at ‘The Port’ (for Athens), on their way to Port Said. The Shipping Companies preferred saving hundreds of miles, by picking up passengers at Navarino Bay on the West Coast of the Peloponnese. This was no doubt a good saving in time and money for the shipping lines, but it meant a long drive over treacherous mountain roads for the passengers.

A modern jet takes no more than three and a half hours from London to Athens or Istanbul. Before they came along, it was a whole day’s journey in a Viking, calling down at Paris and Rome on the way. It just wasn’t possible to make a same day connection for Izmir. So, I was faced with a night in Athens.

It was late in the day when I caught my first view of the City, as we were making our final landing approach along the coastline. By the time the airport bus pulled up at B.E.A’s office, close to Constitution Square, sunset was well past, and the streetlights gleamed against the darkness of night. I only had to cross the Square to reach my hotel, the “King George V”. Still some years before Greece and her Islands were to become entrenched upon the post war tourist map; I felt that a world of mystery and adventure lay just beyond the hotel foyer. A mixture of tiredness and apprehension of what lay ahead the next day, kept me in my room that night.

I only caught a brief glimpse of Athens’ ancient columns, on the way out of the City, next morning. This time, the aircraft was a DC3 belonging to Turkish State Airlines, Devlet Hava Yolları. More commonly known then as ‘DHY’, their name was eventually changed to Türk Hava Yolları, or ‘THY’. Had it been some fifteen years later, when high altitude machines were introduced on to the route, I would never have been able to log the views that I saw that day, into the picture album of my mind.

No sooner were we off the ground, and climbing over hay brown rounded mountain peaks, than the landscape gave way to a white flecked blue Aegean Sea. An hour later, and more sparsely covered mountains rose from a new coastline looking even more wild and remote, with no signs of civilisation that I could see. Many a dark deed took place on Chios. I didn’t know that then, else I may have had second thoughts at staying any length of time in the region. Still, that is all in the past, and the curious can learn all about ‘Black Ali’ in the chronicles of the Island of Chios. A narrow sea channel separated the Island from the Mainland, which looked nothing at all like my expectations of Turkey. The vast mud flats that spread out below hardly fitted my imagined land of the Sultans and scimitar brandishing horsemen. I was tossing this idea around in my mind when the seat belt sign went on. Our ‘plane turned to cross the Bay of Izmir, and we landed at the old airport, which lay beyond the hills to the south of the City.

Lydia and Nadia were both there to meet me, and suddenly the World felt friendly again. The ordeal of the lonely traveller was behind me, and the alien land that now lay before me, became acutely interesting, rather than a place of dread. They led me to a hut where plain clothes customs and immigration officers hurled questions in a tongue like no other that I had ever heard before. The girls appeared to take charge, answering all of the questions for me.

Not owning a car, their father hired a chauffeur driven vehicle whenever the need arose. So, I was spared the rigours of a Turkish bus ride on my first drive through Izmir. How different it was, all those years ago. I guess one would still recognise the poorer areas on the outskirts. Small towns all over Turkey remain much the same, and one could never miss the Roman Viaduct.

The main streets winding through to the centre of Izmir in 1956 were lined with the old houses and buildings that had been there long before the great fire of 1922, which destroyed the eastern end of town. The towering apartment buildings and car-covered pavements were years away, and I count myself fortunate to have known the character of old Smyrna, with its streets of balconied houses. Enclosed and jutting out from the upper floor, these protruding boxes allowed ladies to sit in privacy and watch all that happened in the busy street below. Those too, were the days when it was cheaper to take a horse drawn ‘Fayton’, for a bumpy ride over the cobbled roads, than to call a taxi. With heaps of tourists, and most of the cobbles gone, it is now the other way around.

|

The girls’ family consisting of mother, father, and three aunts, lived like many other of the ‘European’ population, on the northern side of the long Gulf. Getting there from the Airport meant driving through Izmir to the far end of the Bay, and right around to the fashionable suburb of Karshiyaka. The twin’s excited chatter lasted all the way, outlining plans for the week ahead, interspersed with questions, and Izmir’s latest gossip. At the same time, I was drawn to the passing scenery with a curiosity that was more intense than when seeing other countries for the first time. Heaven knows what I expected to find, perhaps a melange of Arabia and Europe? Yet, this was unmistakably a Mediterranean country, with familiar orange tiled villas, until a closer look revealed the intolerable abject poverty that predominated all around the outskirts of the City. In the City Centre, fine looking boulevards linked the waterfront promenade to the two main stations, and to the Culture Park and Squares on the new side of town. There was such a void and contrast from this part of town, to the narrow bazaars that formed a maze in the Konak, or shopping area, which had been untouched by the great fire.

|

Lydia’s house lay several streets back from Karshiyaka’s bay side promenade, which paralleled Izmir’s waterfront across the Gulf. The house was typical of old Smyrna, with the upstairs balcony overhanging the street. A wide marble-floored entrance hall, led past a glass doored front room, to the living room at the back. A large dining table filled the centre of the room, but the main feature to catch the eye, was a white porcelain stove that stood near the hallway. Its flue, a large black pipe, went up to the ceiling and along the wall to carry the flumes out at the back. Below, a divan filled the space between the stove and window, which overlooked the back yard.

|

When at home, Mr. Zacharie used to sit near the window trying to listen to his radio, oblivious of the constant chatter of female voices that clamoured throughout the house. Utterly confusing for a visitor, any conversation, which was normally in French, could switch in mid sentence into Greek and back again. A knock at the door, and a caller could enter with a hail of greetings in Turkish, turning to English out of politeness as soon as my presence was noted. Some of the cousins were of Italian extraction, and when they called by, another linguistic dimension was added to the confusion of mixed communication.

People of the Aegean have always added a qualifying ‘beautiful’ to the City’s name. So for Greeks will it ever be known as ‘Oraiya Smyrna’, whilst to the Turks it is ‘Güzel Izmir’. In the light of day, it was easy to see that the title was well earned. The main shopping street in Karshiyaka made its way from Lydia’s street, past enticing patisserie shops to the Ferry Station. A palm lined waterfront promenade dotted with restaurants spread to the left and to the right, as I took in the scintillating view before me.

Barely able to make out the buildings and warehouses that line the distant shore, the ferries plying their way across the Bay, clearly identified the direction whence lay their three main ports of call, at Alsanjak, Pasaport, and Konak. Behind the City, high mountains filled in the background, and tinges of snow on their peaks, scraped a brilliant blue sky. Despite the chill in the air, the Sun was sparkling on the water, to add a breath of warmth. My spirits soared with exhilaration as I savoured the whole scene and the ambience of my surroundings.

Suddenly my reverie and the relative silence, was broken with the harsh ringing of a bell in the Ferry Station. Lydia called out to hurry, and we raced across the paved forecourt, just making it before they closed the gates. We had hardly boarded the Ferry, through the wide-open entrance amidships, when the lines were let go. Karshiyaka’s foreshore receded rapidly as we forged ahead across the now choppy waters.

|

Down below, Lydia spotted some of her Turkish friends and a chorus of ‘Nasılsın’ rang out as we joined them. With barely fifteen minutes to the first stop at Alsanjak, there was little time for refreshments. All the same, there was a boy with a tray, who wended his way between the aisles, calling out ‘Çay Taze’, ‘Gazöz’, and ‘Sanoviçlar’, enticing passengers to try his fresh tea, lemonade, and sandwiches. After disembarking, people at Alsanjak, our course ran in line with the City waterside. Now, I was able to see at close hand, the modern flats facing the sea, all of them built since the 1922 fire.

The Ferry Station at Pasaport, built out on a harbour mole, stood out like an outpost of the old, on the verge of the new. Since our ferry was returning across the Bay instead of continuing on to Konak, we stepped ashore, with the crowd, and then took one of the faytons that were standing waiting nearby. Both cab and horse had seen better days. Still, it was comfortable enough in the cushioned seat that was protected from above by a roof, extending almost to the driver. A slight jolt and we were on our way past the long bare walls of the tobacco warehouses, which faced the Harbour, at that time. The ride in one of the old faytons was pleasant as long as you were on one of the modern smooth surfaced roads. The minute it struck a cobble street though, the wheels bumped along, jarring every bone in the body.

Many years earlier, Izmir had had trams. The rails were gone, but blue and silver single decked trolley buses were able to use the overhead wires. They ran all of the way from Alsanjak along the front, through the town. Then they continued right on to the end of all the urban sprawl, on the road towards Cheshme. Alas, the character of old Smyrna has nearly all gone. Tall modern office buildings and apartments have replaced the evil smelling warehouses. Restaurants and chic tourist shops now face the harbour. The trolley buses have followed the trams into the forgotten past, with buses and the dolmush (meaning ‘stuffed’) shared taxis, taking their place. The old picturesque Clock Tower is still there, only it has lost its pride of place as centre of a roundabout, between the Town Hall and the Konak Ferry Station. Supermarkets and Stores have arrived, although, at least, citizens still prefer to shop in the maze of narrow crowded bazaars that meander amidst a patchwork of ancient buildings, behind the Town Hall.

|

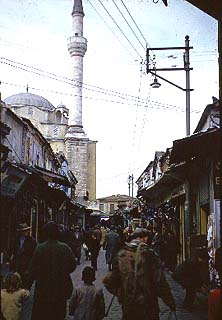

Lydia led me through the labyrinth. Suddenly, it was all familiar. Here were all the open fronted shops that I had known in Aden. People jostled and pushed past, in the middle of the narrow streets, while vendors cried out ‘Buyurun’, to attract some custom to their stall. The walls and every bit of space were packed with pots and pans, shoes, cases, linen, or whatever else they had to sell. Here and there a Kebab house wafted out on the air, the spicy smell of lamb roasting on a turning spit in an open corner window. The heat from the stack of glowing charcoal shelves next to the Spit, lent a little heat to the wintry day. Above the noise of people’s chatter, trade and barter, loudspeakers amplified the sound of classical Turkish music. To my western ear, it was no different from the wailing noise that had rung through the alleyways of Steamer Point and Crater [Aden]. I hadn’t been impressed whenever I had heard it before, in Aden. Yet, now, it was like some long lost friend.

The big difference was in the people themselves, and their dress. There were no skullcaps, loose shirts and lunghi kilts here. Western clothing had become well established, replacing all of the colour of the robes and turbans of the old Ottoman Empire. Long since banned, the Fez, in itself an import from Venice, had been replaced by the flat peaked cap, worn above a mustachioed face. As I walked along I realised that there was another important ingredient in the Turkish Bazaar that will perhaps, ever keep the western borderline farther east. Ladies were free to walk the streets, free from any shielding veil.

Lydia clearly knew her way to the farthest reaches of this bustling street complex. Her pace quickened as we neared an even narrower lane, where the Sun’s rays could hardly penetrate. This was the Street of the Jewellers. These shops had window fronts, and sitting down inside one of them, did seem a good way to escape the crowds for a while. The owner, Pierre Borg, was a distant cousin of Lydia’s and was of Maltese descent. Pierre’s jeweller’s shop was one of Lydia’s favourite shopping destinations. If she wasn’t buying she was exchanging. Pierre would produce a black rectangular stone and rub the ring she wanted to exchange on it, and then put some drops of some kind of acid on the marks to assess the carats. In later years for some reason, we went to a shop run by Pierre’s son which was on a nearby corner in the Pazar.

I was soon introduced to another local custom. A quick call from the doorway, and a boy came running carrying a tray of tea, coffee, and cooling soft drinks. This was just one more of the multitude of new sights that I had discovered since my arrival in Izmir. The brass tray was suspended by two brass rods that were joined above the tray by a ring. Narrow waisted Turkish glasses were filled with pale amber Turkish tea, and miniature coffee cups held the strong black bitter liquid that was to take me long to find palatable.

Before the week was out, we were to pay another visit to the jeweller’s. This time to pick up engagement rings.

Lydia’s father was having a beach house built at Kalabaka [in Turkish Kalabak mah., a district of nearby Urla] a secluded spot on the southern shore of the Gulf. Being close to completion, he took us all out to see it, while I was there. As before we crossed by ferry to Pasaport, where he had a car waiting. Once we were past the City limits, the road ran straight for a good distance. Eventually it deteriorated in places, to little more than a rough track, twisting as it climbed and negotiated the odd hills along the coastline. The countryside looked dry and rocky with some scrub, where local farmers eked out a living from the stony ground.

|

At last, after a good hour’s drive we came over a hill and down to the right stood a solitary group of chalets, between the road and the sea. No more than half a dozen in number, some already had a small garden established between road and house. The largest was a double storey with bougainvillea growing up and around an upstairs balcony. A low concrete wall held back the Sea from the shored up beach, which was little more than two or three metres wide. The house that we had come to see was practically ready for the coming season, needing only a coat of paint, and loggias, which were to be erected over the raised verandas that extended from both front and back.

I was just taking some photos of our little group, out on the roadside veranda, when an elderly local appeared. He was introduced to us as the caretaker, Mahmoud. An incongruous sight to my eyes, the old fellow was wearing western clothes that had seen many a better day, while his head was loosely wrapped in a turban. Inviting us to see his house, he led us up a path, which led up from the other side of the road, picking its way over the rocky ground that supported only scrub and thistles. Mahmoud’s modest dwelling was just over the brow of the hill, a rough stone cottage where his wife awaited to invite us in. Sparsely furnished with Turkish carpets, and low divans set against the white washed walls, the room was cozy enough, despite its primitive surroundings. Offered a cup of the bitter black coffee, I held back the shudder of distaste, lest I hurt the feelings of our hosts.

Back in Karshiyaka, Lydia took me on a round of visits, to meet all of her relatives and friends. Before long, I was getting quite used to the inevitable offer of tea or Turkish coffee, until one morning when I was a little taken aback, having been presented with a glass of water containing a globule of some dark substance at the bottom. Lydia appeared amused at my obvious confusion. When the old lady that we had come to visit, shuffled out of the room in search of biscuits, she explained that it was just a spoonful of jam. “Drink the water and eat the jam”, whispered Lydia. “It’s a local custom.”

|

I was to learn a lot about the Izmir customs and traditions with each passing day. The odd blend of European and Middle Eastern life went deeper than I had thought at first. The more I learned, the more intriguing it became.

|

My week in Turkey was nearly over, when Lydia’s father suggested that I really should see Ephesus before I left. This was no mean undertaking at the time. It was to be a good few years, before the tourists would arrive in droves, and excursion could be organised to facilitate the sightseeing. Being a weekday, nobody else was able to join us. Lydia and I set off early in the morning, once more by ferry to the City, where we took a cab to the Bus Station. It turned out to be no more than a large clearing at the far end of one of the boulevards. The air was filled with dust as people crossed in every direction, to find the bus that they needed. My heart just sank when I saw the state of the dilapidated old charabancs, gaudily painted in bright and fading colours. There were no neat destination boards. We had to find the bus for Selchuk the hard way. Drivers stood alongside their vehicles, and trying to overcome the noise of all the revving engines, they strained their lungs, to announce their route and final goal. Need I say, there were no timetables either? They simply left when every seat was taken.

With a full load, I naively thought that we would have few stops on route, possibly pulling up only to let people off. What a hope! There were probably a dozen stops before we even reached the countryside, by which time so many were packed inside, an ant couldn’t have squeezed its way through. Nevertheless, the driver still pulled up at a small roadside village, when he spotted a few more hopeful travellers. Despite the cries of protest from within, he climbed out, walked around to the Passenger’s door, desperately trying to find some means to fit another body in. Some two hours later we finally arrived in the old town of Selchuk, which is built over some of the later ruins. Here we were able to hire a taxi, to take us down to the site of the ancient city.

As I look back over the years, I count myself fortunate to have seen the ruins as they were in the Fifties. Whilst the modern cities of our world have grown with rapidly increasing populations, and tower like architecture, Ephesus is undergoing a drawn out metamorphosis, due to our insatiable curiosity for knowledge of life in ancient times.

It will be perhaps another lifetime or more, before the rest of Ephesus is uncovered. What we see today is not a lot greater in area than when first went there with Lydia. The transformation that has taken place has been more to do with reconstructing the original excavations. Now we have a very good idea of how it must have looked in the days of Mary, John and Paul. The Great Theatre that I first saw, consisted of fallen stones and pieces of columns strewn around the ancient stage. This faced an enormous grassy slope reaching so high up the hillside, that a person standing at the top, looked no bigger than a tiny tot. It took some stretch of the imagination to visualise the angry gathering of silversmith workers roused by Demetrius. Today the grass and weeds have gone, and steps of seats spread once again to the top. The Stage has been cleared, and from time to time, cultural events are held in the old arena.

The baths behind the Temple of Herodotus, were piles of rubble. Though not fully restored when I saw them last, you could at least understand the lay of the different rooms, whilst the public communal toilets leave nothing to the imagination. The missing parts have been replaced with concrete, and it is easy to see what is old and what is new. The Library of Celsius told little of its past, that day in 1956. Since then, modern architects have raised again the street facade, which today’s tourist can enjoy. Perhaps, one far off day, our sons and daughters will see the whole city in its former glory, just as it was when Greeks and Romans trod those marble stones.

I imagine that it will be quite a sight, when Ephesian streets are fully restored. Future generations will stroll along the colonnaded Acadian Way, and will admire the splendour of Ancient Greece. By then the tread of the tourist foot will have hollowed further, the marble paving that has borne the weight of Saints and Senators. I am happy enough to remember the half covered deserted site, where we could walk alone, without busloads of visitors to contend with.

The bus ride back to Izmir was free of the crushing throng that had accompanied us on the down. The only picture that comes easily to mind, is that of a straw coloured flat plain, with a small black train silhouetted in the distance. The irregular outline of the engine bespoke its archaic framework, while the two carriages which had an extended roof at each end, above an outside-railed platform, would not have been out of place in a western movie. When I queried why we hadn’t taken the train instead, thinking that it would have been more interesting and certainly more comfortable than that morning’s ordeal, Lydia explained that it took twice as long as the bus.

At the end of the week, Lydia arranged an evening out with Gemma, her cousin, and Gemma’s American fiancé, Johnny. A soldier in the American Army, Johnny was doing his National Service, and was based in Izmir. He got tickets for us all to go to the American Cinema one evening. Listening to everyone’s chatter as we filed inside, and hearing English spoken all around, was almost like coming across an Oasis of refreshing comprehension in a desert of unintelligible speech. The strain of trying to communicate was lifted for the evening, and I began to relax, despite the alien accents that assailed the ear.

Gemma’s home was in Izmir, and neither she nor Johnny had to take the ferry, as we did, that night. They came along to the Alsancak ferry station, and waited with us, to see us off on the last ferry. Not that we needed an escort, for the streets in those days, like most towns in the World, were quite safe to walk alone at night. The large hall of the ferry station was almost empty, with only a few souls sitting on the wooden bench that ran around the inside wall. It was a chilly night, and silent, for all the traffic on the road outside, had died away. As we talked the time away, a solitary Turk paced up and down over the tiled floor. Trying to keep our minds off the cold, that did its best to penetrate our overcoats we chatted on, until one of those moments when none of us had anything more to say. Suddenly, Johnny began to chuckle. We hadn’t noticed it before, but the lull in conversation turned all our minds to the only sound that broke the stillness of the night. The perambulating Turk had squeaky shoes, as did most who wore the local footwear. Hardly noticed in the daytime, the creaking leather echoed like a raucous crow in the near empty hall.

All too soon it was time to leave Izmir. With my departure I learned another local custom. The car was at the door, and all of the family had gathered around the entrance. Then Angele, the youngest aunt, appeared with a large jug of water. When the moment came for us to get into the car, the jug’s contents were ceremoniously thrown out across the steps. I might have said something like, “That’s not very nice”, thinking that Angele was getting rid of the water, at a rather inappropriate time, until Lydia told me that it was to ensure a safe journey for the traveller.

December 1956 - At end of voyage home from Melbourne.

It was a strange homecoming. It wasn’t at all like the last time. But then, I wasn’t really at journey’s end. After getting through Customs in the morning, it took until the afternoon before I finally got to Durley Avenue. Mum had arranged a ticket through Derek, for a flight, this time to Istanbul, on the following day. I had to spend a night there before flying down to Ízmir, and it should have been another memorable first visit. Instead my eyes were focused more on what lay ahead. It had been a long tiring day leaving Heathrow in the morning, with stops at Paris, Rome, and Athens. Darkness having already descended over the far edge of Europe, I hardly noticed my surroundings from the Airport Bus, on the way into Istanbul. Derek had booked a hotel as close as possible to the City Air Terminal, so it was only a step down the road, and some moments, before I was comfortably settled for the night.

I had little opportunity to see anything of Ístanbul the next morning, having had to return to the Airport with the dawn. So here I was back among the now familiar sounds and smells of Turkey. Sitting in the departure lounge the redolence of Turkish tobacco permeated through the air, while the tap of footwear on a hard bare floor echoed round the well worn surroundings. The cabin of the Dakota too, stirred a feeling of familiar contentment. There was something cozy about the use of pillows handed out by the stewardess to support your meal tray. I wasn’t a stranger in this part of the World anymore, and I was almost home.

The whole household at Karshiyaka was in a fever of excitement and preparation. First there was Xmas and the New Year coming up, and then the wedding which was set for a Sunday in the middle of January. The noise and shouting between the Aunts, the Maid, the Cleaner, and continual callers was incessant. There was a whole round of formalities that I had to go through, registering as a resident, posting bans at the British Consul, a medical examination, which was little more than an inspection of our hands, and approval from the Muhtar, who is roughly equivalent to a Mayor [of the district].

We were forever being congratulated by Lydia’s friends, in the street, on the ferry, and on countless visits to friends and relations. After the initial greeting the conversation would race on in French, Greek, or Turkish, while I stood or sat on the side line, feeling something of a trophy that had just been exhibited, looked at once, and then ignored. At least that is how it all looks to me now. Any irritation I felt then, was quickly smothered in all of the excitement of the day.

Wherever we went in Ízmir there were twins. There were Pairs and Pairs of them. A few years later, some publicity was given to a northern suburb of London, where the same high incidence of twins was well above the normal bounds of chance. “Was it something in the water?” the papers asked.

Christmas came with all of the bustle and happiness to be expected in a Christian country. Some Turkish families, though Moslem, joined in and decorated their own trees with seasonal gifts. The household noise grew louder than ever, getting ready for the big night on Christmas Eve, when all of the uncles, aunts, grandparents, cousins, and friends would arrive after midnight mass, to feast on a variety of cold fish dishes. During the days leading up to New Year, we went through a whole round of parties and nights out, culminating in a large club over the Konak Ferry Station. The room was packed with tables as close as possible to accommodate the revelling multitude. With blinds left undrawn, the Harbour was ablaze from strings of lights on all of the passing boats and ferries.

When the band played “Auld Lang Syne”, I was struck with the incongruousness of the setting, wherein the players with hardly a word of English between them, never mind Scots, had taken up Rabby’s famous air. In a moment it was gone, as the band swung into Turkish mode, attacking the sentimentality of all the locals. A floor show followed with the inevitable belly dancer being cheered on by her applauding admirers.

All the festivities over, there only remained two weeks to the wedding. Lulled into a sense of euphoria by all of the celebrations, I hardly gave a thought to what I would do, once we got back to England.

I wonder if anyone else ever had to go through so many marriages in such a short time? The Turkish authorities didn’t recognise religious weddings. So, we had to present ourselves the day before, at the local registry office, where we were afforded all of the full honours of a Turkish marriage, ending in congratulations from each official. Then there was a hand out of sugar almonds, and a drive back to the house with handkerchiefs tied to the radio aerial. The next day being Sunday, the wedding ceremony was incorporated into the main Service. Myself being Anglican, we had had to get special dispensation from the Bishop of Izmir to allow the Priest to perform the rites before the Altar, instead of out the back. The Church was packed, and I can only say now that it was all very unnerving.

There only remained the formality of getting recognition from Her Majesty’s Government, and to this end we made our way on a wet Wednesday afternoon, to the British Consul. Here it was explained that whilst they could recognise the Turkish marriage, it was a long drawn out procedure of red tape. It was to be much easier for the Consul to marry us again, since the banns had been published in the Consulate for the required time. The deed was done there and then, standing in our wet raincoats, before two witnesses, a Turk and a Greek, who were employed by the Consul. Everything else was much of an anti-climax after all that, and by the end of the month we were on our way to Istanbul, for a couple of days before flying on to London.

The bastion of Christendom through the long dark ages, so richly endowed in its prospect around the Golden Horn and Bosphorus, was and is the most stimulating place on Earth. I knew a little, but had no idea of the wealth of history and culture deposited where Europe meets Asia, by humankind, over the millennia, nor of the promise of adventure and discovery seething through each street and alleyway. An agglomeration of secrets, intrigue, and allure, capture the imaginative wanderer, drawing the inquisitive ever deeper into its cauldron of people, time, and treasures.

Istanbul is a perfect example of a city that must be researched by the traveller before going there, if one is to get the utmost satisfaction from the visit. When I stood beneath the enormous canopy that roofs ancient Aya Sofia, I felt the magnetism, but could only see the vast empty chamber, great pillars, and cold dark stone floor. How was I to visualise the terrified congregation who in 1452 had cowered and ran in every direction, when the scimitar wielding horsemen of Mohamed the Conqueror rode into the great church.

One thousand years of Christendom, followed by a half millennium as a mosque, has left an unmistakable aura, and not knowing St. Sophia’s history was my loss. In the Sultan’s Treasury, the wealth of jewellery, history, and ancient artefacts instilled a feeling of great awe into the very soul. It didn’t pass on one word of all the horrors that had taken place within the Palace walls, nor of the love lorn lives within the Harem. A little research before a visit makes all the difference. Sure, a tour guide will fill in a little of the background. But, they usually only hand out the cold bare facts which so often fall upon deaf ears. Reading light historical tracts is enough to change the whole perspective of a globe trotter. Without a little prior knowledge, one stumbles about in a mist, marvelling only at the scenery and any outstanding ‘objet d’art’. Doing a bit of homework beforehand, it all comes into sharp focus. Instead of just another church or castle, the past is conjured up in the mind’s eye, bringing life and understanding to everything seen.

I guess that Mum, Dad, and all of the family felt a little cheated in being unable to attend the wedding. People hadn’t got used to the idea of travelling as far as France, never mind to the other side of the Continent. Another Reception just had to be held, and once more Lydia had to don her wedding dress, for a grand evening at the ‘Little Abbey’ in Missenden, where everyone could meet her, and mark the event in time honoured fashion.

Later Years – we had many holidays back in Izmir and Kalabaka until the family were gone. On one of those visits Henri told me what it was like on that awful day in 1922 when the city was burning. Someone told them that they could find refuge with Christian families around the Bay at Karşıyaka. Henri was just 20 years old at the time and though he never mentioned it that would have been when he met his future wife Marie Damiano. He also told me of his friendship with his old schoolfriend Onassis. Sometime in the 1960’s I think it was, Onassis’ yacht called in at Izmir and Henri was invited on board where he had lunch with Lady Churchill who was a passenger on the yacht.

Henri Zacharie worked for most of his career with Van Der Zee Shipping Agency and eventually became their manager and also an Honorary Consul for Denmark in Izmir.

Notes: 1- Henri’s brother Joseph was the Manager of the Ottoman Bank in Izmir. Joseph’s grand-daughter Chantal Zacharie or Zakkari is fellow contributor to the website and joint author of ‘State of Ata’.

Henri Zacharie was born in Edirne and his immediate ancestors were from the Island of Chios. His mother was the daughter of an Austrian Railway Engineer working in Turkey.

When you look into the history of the Zacharie’s you will find them extremely colourful. I have no evidence that they are descended from Benedetto Zaccari who was a Genoese Admiral appointed by the King of France to clear the pirates out of Chios. He became Lord of Chios in 1314. Benedetto Zaccaria was Lord of Phocaea, or Phokaia, (Greek: Φώκαια) (modern-day Foça in Turkey) from 1288. One of his sons, Martino Zaccaria was taken by the Turks while attending Mass in Smyrna Cathedral and was beheaded in the courtyard outside, on the 15th January, 1345. It seems that there were many other Zaccaria’s in this family and some must have remained on Chios. If there is a connection between the Zacharie’s of Chios and Izmir with the Zaccaria’s of Chios and Smyrna, then this must make them one of the oldest established Levantine families.

Henri sold up his house in Karşıyaka in 1964 and moved to a flat in Alsancak. By then Izmir was already changing and quite different from the city I first saw in 1956. I well remember old Mr. Borg whom I believe was a relative. We paid quite a few visits to his jewellery shop and his son’s shop in the Bazaar area at the back of Konak. I would like to know more about this family. Also I still haven’t noticed any mention of the Vernazza family who were also distant relatives.

Charles Joseph Zacharie whom Lydia knew as Joseph or ‘No No’, gave me a copy of the Family History that he had traced – mainly in correspondence with the Roman Catholic Church on Chios. This is quite extensive but the main points are that Charles traced the family back to Cagi Giovanni Zacharie who lived on the Island of Chios from 1796 until he died 26 Nov 1867. - summary:

2- In order to assist Mr Hutton to go deeper in to the Zacharie family history and more, please contact him through: calum33[at]bigpond.com