segment of her unpublished history book by Helen Leggatt

Foreword

Smyrna, once known as “The Pearl of the Aegean”, is one of the oldest cities in the Mediterranean. It had been in the Ottoman Empire since about 1425. By the end of the nineteenth century it had become a sophisticated and prosperous port with a large European population.

Maudy Campling was born and brought up in Turkey. At the age of 83 living in George, a coastal town in South Africa, she decided to put down her life story. Her “Memories” covered one hundred years of her family’s story in the Levant from 1841-1941.

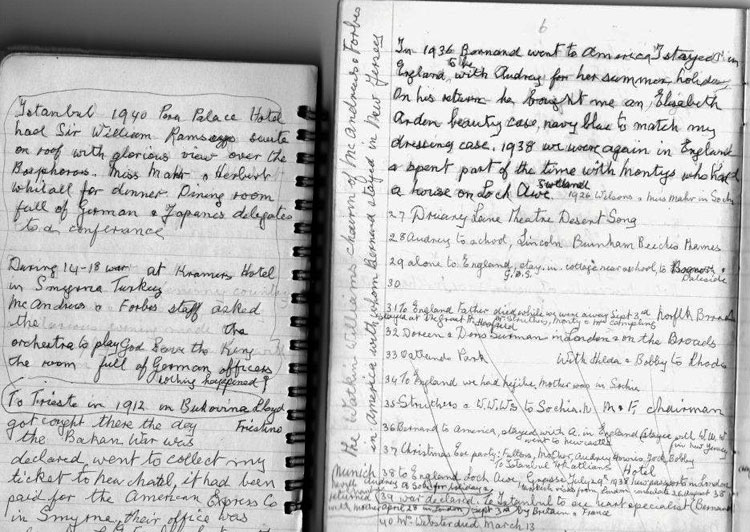

When her daughter Audrey, a well-known South African botanical artist died in George, a mutual friend going through Audrey’s belongings came across six note books, photos with dates on them and letters, all neatly tied up by Maudy. There was also a small wire bound note book written in pencil, pen and ink, ball point in different colours, with some parts crossed out, others bracketed and even written up the sides of the page. Some pages were badly faded needing patience to read and re-read. The wire-bound note book used as an address book by Maudy was divided into nationalities of friends in Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey. Some were friends who had fled from Turkey to Greece after the Greek-Turkish war of 1922. The book also contained a list of her favourite books, plays she had seen, hotels she had stayed in, bits of gossip as well as fascinating historical facts. This was a historical treasure trove of the life and times of Maudy Campling.

I was initially drawn to a 48 page fawn exercise book in which I found Greek nursery rhymes and popular songs of my childhood. Greek customs, funerals and religious celebrations were described in great and accurate detail. As I flicked through the pages, French songs, Italian sayings, sprang out.

With my Greek background I was fascinated by the story of Maudy. Going through her notes (with dates), I saw history unfold before me. Many Greek myths about Turkey and the Turks remembered from my childhood days have been put to rest thanks to Maudy’s accurate notes and dates.

Yvette Van Wijk, Audrey’s friend, having rescued the note books and photos suggested that I help her to go through them. I am most grateful to Yvette for entrusting me with all the material for this book. I would like to thank Basil Bey for his help and my husband Hugo for his encouragement and patience.

In your hands you hold an interesting account by an ordinary woman living in the Levant, an area of distinctive European influence in the Eastern Mediterranean. This is a story of a bygone era.

Chapter 1 - My Family

Smyrna, once known as “The Pearl of the Aegean”, was one of the oldest cities in the Mediterranean. It had been in the Ottoman Empire since about 1425. It had become a sophisticated and prosperous port with a large European population.

The Marcaras of Smyrna were a long established Armenian family with the original name of Marcarian. As did other Ottoman Christian families, they tried to assimilate with the European community. Thus Levantine families tried to hide their origin, establishing links with European families via marriage and business interests. At some stage the Marcarians applied to the Spanish consul to get the status of “European protégé” and a name change to Marcara. This was costly and one had to be rich and it seems that the Marcara family paid Spain for their protection. They also paid the Ottoman authorities for a “berat” or decree which gave them the same trading advantages as the European subjects.

My paternal grandfather, Joseph-Paul Marcara1, was a jeweller in his father’s firm in Smyrna. In 1843 he was travelling overland from Europe back to Smyrna. In Trieste on the northern Adriatic coast he had to wait for a passage on a boat to his home port. Whilst waiting in Trieste, Joseph-Paul killed time by walking and exploring the many streets, parks and beautiful buildings in that city. One day he happened to be going past a convent. Stopping to admire the building he saw a face at a window. After that he walked by every day. He was fascinated by the young girl sitting day after day sewing or knitting at the window. Unable to get the young girl out of his mind, he knocked on the convent door and asked to speak to the Mother Superior. She of course would not tell him anything about the girl except that the father of the “face at the window” was a ship’s captain, who was due to arrive back soon from a trip. The Mother Superior having supplied Joseph-Paul with the name of the ship sent him on his way.

He waited until at last the ship docked in its home port and Joseph-Paul met Captain Covatchich, the captain of a Lloyd Triestino sailing ship. His wife had died giving birth to Anna, eventually my grandmother, who was born in Trieste on January 26th 1824. Her father was rarely at home and so, unable to look after the child due to the nature of his work, he left Anna in the charge of the nuns in the convent where she had remained for the next 17 years until young Joseph–Paul saw her at the window and asked her father for her hand. They were married at once and he continued on his voyage with his young wife. They settled in Smyrna where in due course Anna produced nine children. Joseph, my Father, was one of them. I was told the story of this meeting by my Grandmother Anna shortly before she died in 1907. Was there ever a more romantic encounter than this?

My father, Joseph, was 41 and a widower in 1887 when he travelled to England on business. He owned a small shipping agency in Smyrna, also a merchant and chandler business. In England he had interviews with several ship owners with a view to getting their agencies. He then decided to stay on for Queen Victoria’s Jubilee celebrations due to take place the following year.

One of Joseph’s interviews was in London with a Mr Olivier, a Frenchman who owned a holiday home a few doors from Father’s house on the quay at Kordelia [Cordelio = Karşıyaka] on the western side of the beautiful Bay of Smyrna. The Oliviers lived mainly in Paris and were friends of my Uncle Tom Davis, my Mother’s brother, and his wife Annie who lived in London. Uncle Tom’s sister, Nellie, was staying with them and she was introduced to the Oliviers. They had two small sons who spoke only French and Nellie was asked if she would like to go to Smyrna on one of their ships, stay with them and teach the boys English. She jumped at the suggestion of such an adventure.

Nellie can’t have been with the Oliviers long because she was married to Father on the 29th September 1897 at the Oliviers’ house by a Scottish minister the Rev. Murrey. Mother’s sister, Lily, came over from England for the wedding and stayed with the Oliviers for a short time. She moved in with Mother and Father to wait for and help with my birth. I was born on the 18th July 1898.

When Mother was first married, it was in Smyrna that she was introduced to some Greek customs. Greek ladies from the neighbourhood came to call on the bride and the calls had to be returned within a fortnight. That was all very well but Mother spoke not a word of Greek and her French was limited. Most of the ladies could only speak Greek. When Father came home one evening Mother was in tears. The thought of all the calls she had to make was too much for her. She put on a brave face and started her visits.

Calling time was 4.30 pm. A carriage was ordered and I can picture Mother sitting stiffly, hands gloved, clutching her ivory and silver card case. She would be wearing a visiting dress sent from England of heavy ribbed silk with little blue spots painted on it.

Now let me explain : part of a Greek girl’s trousseau consisted of a big silver tray with 12 jam spoons, one or two silver “vases” for jam, 12 small glass tumblers in silver holders, a large silver container into which, after the jam had been eaten and the water drunk, the spoons were deposited. The wealthier the bride’s family the larger the tray and more elaborate all the rest. Mother had all this explained to her by her English friends who had gone through this ordeal.

On one of these visits she daintily picked up a spoon and dug into the tall, silver jam-jar expecting to bring out a little jam or jelly. To her horror it came up with a little preserved green orange, dripping with syrup, about the size of a Brussels sprout. She could neither bite nor swallow it. So it was carefully placed into her handkerchief and forgotten on her lap. On getting up to leave, it rolled right across the floor and was picked up by the maid much to Mother’s embarrassment.

Mother’s “At Home” day was every second Tuesday of the month. At 4 o’clock the maid brought to the drawing room a tray with tea, thin slices of bread and butter and cake which was most certainly appreciated. Tea time often continued till quite late when husbands called for their wives and stayed on for drinks. If the ladies happened to be French or Italian, liqueurs were served after tea. Hilda and I liked that. We used to drain the little glasses in the kitchen when they were taken away.

It was on one of those visits that we decided they’d all stayed too long. We crept into the room and put a pinch of salt under each chair, having been told it was the only way of getting rid of guests who had outstayed their welcome. We were caught; and it worked that time but we didn’t try it again.

We didn’t stay long in Kordelia after I was born. Father’s business was growing and the little ferry boats that took him across the bay were unreliable, especially in stormy winter weather. It was possible to go by train, but it was a long way round with two changes. The house was sold and we rented for a short time a house in Katrojoglou, a district of old Smyrna.

In 1901 Father bought a single storied house at The Point. We moved in just before leaving for England to stay with my mother’s parents Grandpa and Grandma Davis in Newcastle. All I remember of the return voyage back to Smyrna is that one of the passengers was a Cadbury’s chocolate traveller who kept us supplied with chocolates. Mother was very unwell on this trip. Her illness was soon explained by the arrival of my sister Hilda, born on the 13th November 1901.

After Hilda was born a second storey was added to our house. Upstairs were four bedrooms and a real bathroom with a gas geyser and wash basin. Previously Father had a big, round tin bath with a spout which was carried into his bedroom every morning. A little three legged stool was placed in the centre of the bath and Father’s sponge which was as big as a football. The bath was then filled up with 3-4 cans of hot and cold water. When he had finished bathing, it took the maid and a man to tilt the bath carefully and empty the water into pails. Mother, Hilda and I had our own bath, shaped like a round armchair with a high back. We’d curl up in it and use our own sponges to lather and soak our bodies. When not in use the baths were hung downstairs on the laundry walls.

Our hair was washed once a week with ordinary white soap made of pure olive oil. It was sold in cakes each a little smaller than an ordinary building brick. While still fresh and soft it was cut into workable sizes. It was used for everything in the house from baths, to washing up and laundry. In the bathroom it stood on a marble topped washstand.

Part of the basement of our house was turned into a very cool, summer playroom. There was a swing sent out from England by our Grandparents and also a big doll’s house that father had made for us. From the two basement windows which looked on to the street one could just see the feet and legs of passers-by and we had great fun guessing to whom they belonged. Next to the playroom was the wine- cellar. Father’s guard and manservant, Suleiman, had a room next to the coal cellar, at the back.

On the ground floor there was a large entrance hall, the lounge, drawing room, dining room library-cum-music room, and the sewing room. Apart from the hall the laundry room was the largest room in the house. In one corner it had a big wood-heated boiler. At one side of it was a 38 inches square wooden box with a lid; the box stood 40 inches (1 metre) high. It was for soiled linen and at the other side was a barrel approximately 38 inches across and high enough for the laundry woman to stoop over and put clothes on the bottom where there were some dozen holes about the size of a penny. Beyond that along the wall was a cement gutter on which stood two baths made of wood. One was for washing and the other for rinsing and blueing.

The clothes having been well washed were then carefully laid in the barrel. First dusters and kitchen towels were placed in it, then aprons and bed linen, usually 4 or 5 dozen sheets and pillow cases; Father’s shirts, collars and our garments were laid on top. Finally, the table linen, large damask table cloths, serviettes, tea cloths and smaller items made up the full load.

When the barrel was full, two squares of thick canvas large enough to hang well over the sides were laid over the barrel. The cavity was filled with about two pails of sifted wood ash. By now the water in the boiler was boiling and bubbling. Pail after pail was poured over the ash. This went on until the water started to percolate through all the clothes and drip through the holes at the bottom. At that stage the laundress went home and returned the following day, usually a Tuesday.

Canvas and ash were carefully removed. The beautifully white clothes were lifted into bath number one and rinsed, then blued in bath number two. That was by no means the end. The laundry was carried up two flights of stairs to the terrace above and hung out to dry on the lines. By evening everything was dry except in rainy weather when it was just left out. That was not often.

The third day Angeliki came to do the ironing and starching in which she took a great pride. All the things were brought into the sewing room and placed in neat piles. Anything needing a few stitches or a button was placed apart. Fortunately this big wash took place only about every five or six weeks; in between she came for one day to do mending.

Kyria Verginia, our Greek dressmaker, and Sophia, her daughter, came for two days every fortnight. They arrived early in the morning and stayed till the evening, having all meals taken to them. Their day started with all the things that needed mending. They also made all our clothes, curtains, and sheets.

The cleaning of winter clothes, especially Father’s suits, was also done at home. There was a root sold in the bazaars. One asked for “Riza”, the Greek word for root. It never had any specific name but it had cleaning properties when coarsely chopped and boiled. The clothes after being well brushed and shaken were spread on the ironing table on a blanket. Using a clothes brush dipped into this liquid the clothes were brushed until a white lather came out all over them. They were then rubbed down with a clean cloth and hung up. Once dry they were ready for pressing, free of all grease spots and stains.

When the cold weather was over it was time to pull up the carpets and send them to be cleaned. All the carpets were taken into the garden and beaten and rolled up. Men, whose business was to wash them, would arrive. Loaded onto carts the carpets were taken round the bay where there was a sand or shingle beach. The carpets were spread in the sea where the men trampled them with their bare feet. Afterwards they were spread on the beach to dry. If not quite dry by the evening they were returned and dried in the garden or on the terrace. The salt water brought out the colours beautifully. At the same time the fine matting which had been under the carpets was taken into the garden, washed and spread out to dry. It was rolled up and stored in the cellar with the carpets. In summer the bare marble floors kept the house cool.

Our garden was small, surrounded by a Virginia creeper covered wall and always full of flowers. Steps ran down from the dining room into the garden. At the bottom of the steps there was an arch of yellow Jasmine. It seemed to flower most of the year. There were lots of pot plants in the garden, just as on the terrace on top of the house.

The canaries’ cages hung on the wall, and the two pet tortoises, Tom the big one and Annie (named after our Uncle and Aunt in London) had the run of the garden. They knew their names and came when we called. It usually meant lettuce or cabbage leaves.

Chapter 18 - Root digging

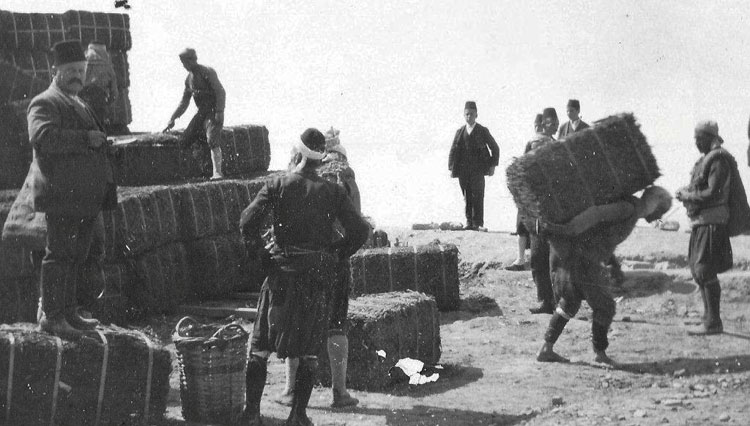

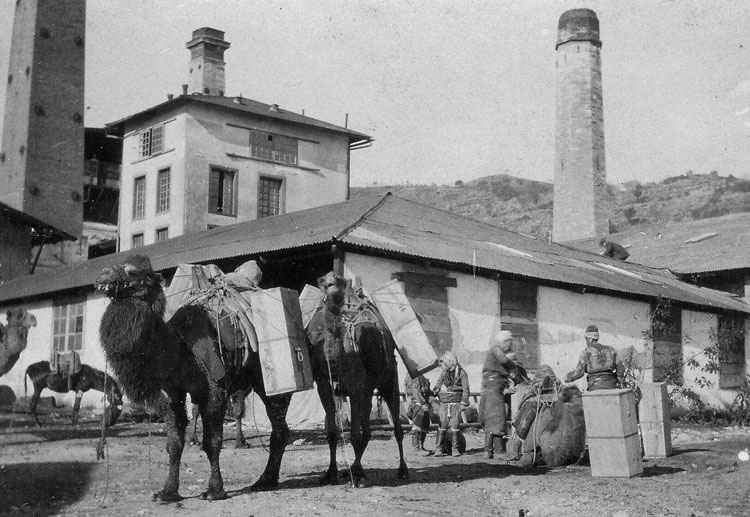

The liquorice extracting factory in Sochia was built shortly after Edward Mc Andrew and William Forbes arrived in Turkey in 1850 and had established their firm in Smyrna. The first shipment of liquorice extract made in the factory left in 1854.

Liquorice, a perennial herb, grew wild around the place long before it was cultivated by Mc Andrew & Forbes. The soft, bright-yellow insides of the roots were fibrous and flexible. Liquorice was used for flavouring medicines with a sweet and slightly bitter taste of anise and was also used in sweets and tobacco. Liquorice roots boiled with figs was also good for prolonged coughing in horses.

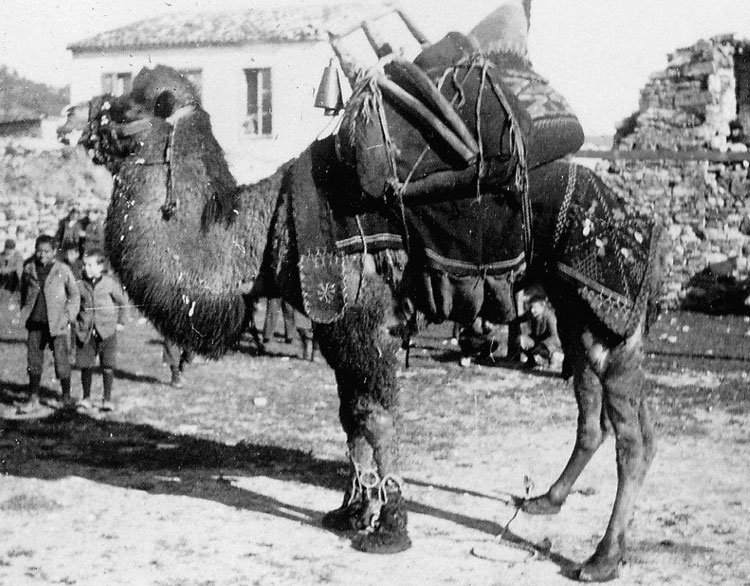

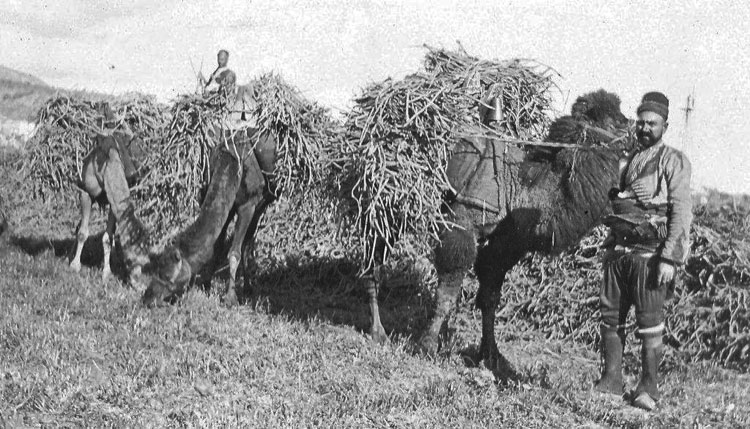

The “Yuruks” whose name means literally “Who Walk”, that is to say nomads, came from near the Kurdistan frontier in eastern Turkey. Hundreds of Kurds would pack up their black tents, load their camels and start for Sochia nearly 1000 miles away. They arrived every spring to dig for liquorice. They brought their black tents and camels with them, and some of their dogs. They walked most of the way as there was no railway. Mc Andrew & Forbes sent a special train to meet them at the nearest railhead to bring them to Sochia. After four months they did the same journey in reverse.

One day all was quiet and the next it would be seething with grunting camels and Kurds in their native costume. All the men had to be signed on, given pick axes and spades and shown which parts of the plains were to be worked that season. Most of it had been leased by the Company from wealthy land owners and farmers. The land had to lie fallow for three years to give the liquorice root time to mature.

The men would depart, and soon the plains would be dotted with black tents and grazing camels. At the end of the week they brought in their camels laden with sacks of root. The sacks were weighed and the men received their pay and a week’s supply of food from the bazaars. Then back to the plain. This continued for about four months and then they loaded their tents and belongings on to their camels and started on the long journey home. Where the tents and camels had been, now was bare earth. There were no trees in there except at the far end where horses, mules and cows grazed as a change from the lower paddock.

Last year’s root having been baled or made into paste or sticks, all was once again quiet. “The Yard” as it was called, gives one the idea of a little back yard, but in reality it was about a mile long and nearly half that in width. As the new root came in, it was loosely stacked into piles and left to dry. When ready it was made into what looked like long, beautifully thatched bungalows. They really were a work of art. It seemed a shame that after a year or so they were pulled down. The root was loaded on trolleys, which ran on railway lines over the bridge and into the factory where it was baled ready for export.

In the stick factory there were long rows of trestle tables with wooden benches on either side with about two hundred girls sat there wrapping liquorice sticks. Audrey like going there because the girls made all sorts of liquorice toys for her. The liquorice was boiled until it had the consistency of tar. It was then poured into wax paper-lined, wooden boxes about 36 inches long by 16 wide and 16 inches deep. They were left open for the paste to cool and harden. When cooled they were cut into 6 inches long and 2 ½ inches in circumference. The women at the tables lightly oiled each stick and wrapped it in wax paper and stamped. One was “Appolo” for one of the tobacco companies; others were made for different firms in England and America. Then they were carefully packed into wooden boxes and finally the boxes were nailed in the carpenter’s shop and the metal bands from the blacksmith wrapped around them now ready for export.

Our dog Borijouka, a solouqui, a special Kurdish breed, slender as a greyhound with black and yellow spots over his eyes had come with the Kurds. He got to be quite well known in town. He was a dreadful thief and stole not only from us but from every baker and stall in the bazaars. He was so quick nobody could catch him. Police messages would be received: “Your dog passed through our village yesterday and stole a loaf of bread from our baker, Ali. He also stole meat from Mahmout the butcher. You owe money to the men. We shall send you the bills.”

One day he decided to walk back to eastern Anatolia. He must have got tired at some point as he was caught and returned to us on a train. Eventually he left with the root diggers at the end of a season to go to where he wanted to be. I hope he was happy.

|

The following photos taken by Bernard Campling are from 1913, the year he arrived in Sokia.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Notes: 1- In December 2012 Ms Leggatt published a limited number of books (cover) comprising the full memoirs of Maudy Campling. Those interested in purchasing a copy (£15 + £5 postage) can get in touch through hl12[at]mweb.co.za.

2- In May 2014 a letter written by Bernard Campling surfaced on e-bay, dated from the difficult period of 1919.