An article written by Emel Kayın2 and translated by Görkem Daşkan3.

The introduction of hotels into the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, as a new means of lodging, manifests a milestone in the development of the idea of accommodation and lodging architecture in the Empire. As an establishment imported from the West, hotels were primarily built in the big cities of the Empire like Istanbul and Izmir, like many of the other new types of edifices of the time. As a trading port city opening to the West, enjoying intensive relations with European states and a home to a cosmopolitan society including a significant amount of Levantine residents, Izmir, set the stage in the region and the era, for the development of the hotel industry together with a number of other novelties. This article aims to deal with the hotels of the area dating back to the period between the 19th and the first quarter of the 20th centuries, and to evaluate and classify 65 hotels in total, in the light of cultural impacts that shaped them as well as their architectural characteristics.

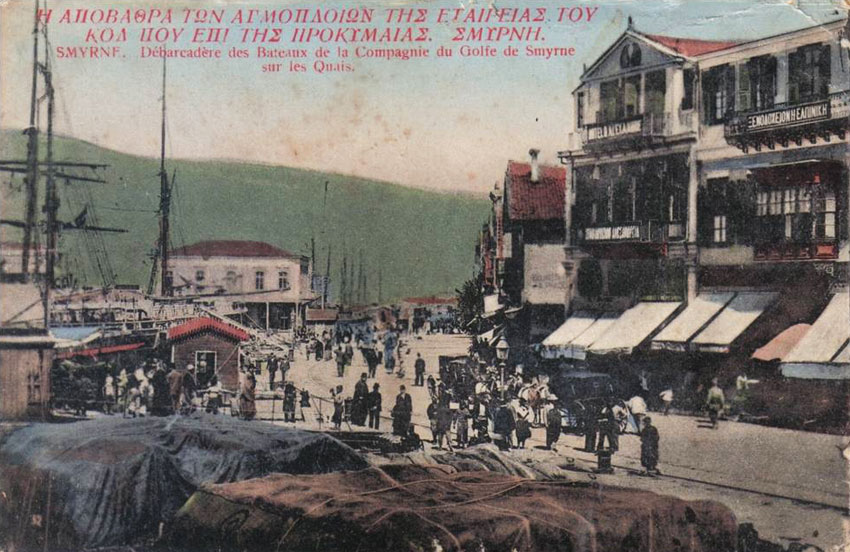

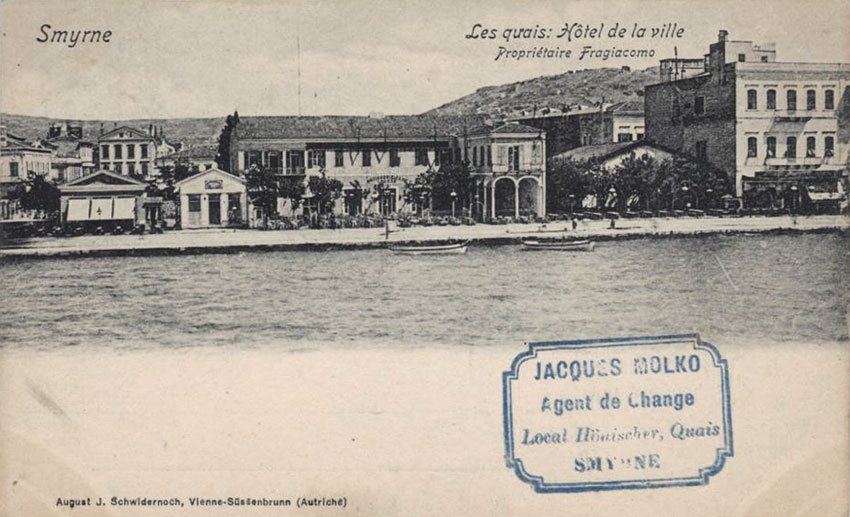

Throughout the 19th century, an era known as the Westernisation Period in the Ottoman Empire, a great number of social, economic, administrative, urban, etc. innovations had been carried out and the impact of such a tremendous transformation could be monitored in its most visible form in hubs like Istanbul and Izmir. In the same century, which was the era of Industrial Revolution in Europe, the Izmir port had gained greater importance than before owing to the Western industries treating the East rather as a commodity market of raw materials as well as a market to import goods to. During this era, long-distance caravan trade had receded and the export of agricultural products to the newly-developing European industrial cities had come into prominence4. A crucial turning point at the time was the signings of the Anglo-Ottoman Treaty of 1838, which granted the British to trade freely in the whole territory of the Ottoman Empire, and of subsequent agreements between the Empire and the other European states5. After such agreements, the Ottoman Empire had become an inviting place in the eyes of European merchants and investors, and as such, the number of the Westerners in Izmir had increased. The constructions of Izmir-Aydın railway and Izmir-Kasaba railway beginning in 1856 and that of the Quay in 1867 were among the most critical investments embarked upon in the Empire at the time, inasmuch as their role in the transport of trade goods6.

While the Western influence in the economic sphere was getting more powerful, the social sphere in the 19th century Izmir was no immune to this power. The population of the city saw an extraordinary change in this period, especially concerning the number of Levantines and other groups of non-Muslims7. Western travellers accounts from the period portray Izmir as by no means an oriental city but a place where foreigners led similar lives to the ones they led in their homelands, and social activities such as attending theatres, cafés, pubs, balls and parties, and club membership mattered greatly in the daily life8.

The intense impact of Western culture in the economic and social grounds in Izmir had somehow spread to architecture and resulted in the building of a set of new edifices, the presence of which was owed to the new lifestyle emerging in the city. One of these edifice types was undoubtedly hotel. Long-distance caravan trades losing momentum and the modernisation of transport systems had definitely had an effect upon the radical transformation in the idea of lodging. However, the reception of this Western establishment hotel in Izmir, as well as in Istanbul, way before the engagement of other settlements in the Empire, was very much related to the cosmopolitan and extrovert quality of the socioeconomic structure enjoyed in the city. The initial hotels opened on the seafront side of the Frank Street and its vicinity had reflected the Western culture represented with local abilities, in not only architectural terms but also in terms of the profile of the users and directors of these hotels and the service that they offered.

The 65 historic hotels of Izmir some of which still remain standing and the rest traceable only in a number of documents and sources can be classified as follows:9

1- Passaged Hotels

. Centre-Passaged Hotels

. Side-Passaged Hotels

2. Hotels with Side Entrance

3. Hotels with Courtyard

4. Hotels Converted from Houses into Hotels

5. Hotels with Different Plan Schemes

. Hotels with Different Plan Schemes of the 19th Century

. Hotels with Different Plan Schemes of the 20th Century

6. Hotels with Unknown Typology

. Hotels with Unknown Typology of the 19th Century

. Hotels with Unknown Typology of the 20th Century

Plan schemes constitute the essential criteria in typological evaluations. The majority of historic Izmir hotels have not survived the test of time and the documents concerning them are quite limited in number. In this article, the analysed hotels will consist of the ones that are still intact at present, as well as the ones that are extinct but with certain documents available regarding their architectural style as well as several sources mentioning them. All the hotels are classified as a result of a careful evaluation.

Hotels with passages, side entrances and courtyards are all characteristic hotels in their own right, as they are one of their kinds in a time when the first hotels of the city ever were built. While these buildings reflect various cultural influences in their structure, setting and architecture, their plan schemes hold unique solutions special to Izmir. All the hotels falling under the above subgroups had been shaped under the common principles produced by a set of conditions, such as urban location, interior-exterior space relations, spatial organisation, structure and material, façade pattern etc.

It is possible to classify these hotels once more into two macro categories, according to their plan schemes, including (hotels with) passages, side entrances and courtyards with respect to their urban location.

- Hotels on the Quayside (with Passages and with Side Entrances)

- Kemeraltı Hotels (with Courtyards)

Within the aforementioned three main groups, we can take on another sub-classification considering the cultural elements in their architectural style.

- Hotels Representing Western Architecture (with Passages and Side Entrances)

- Hotels Representing the Ottoman Khan Tradition (with Courtyards)

The hotels converted from houses, on the other hand, do not reflect much architectural cohesiveness as they had not been initially built to serve as hotels. These buildings are still significant though, in that they constitute a special case within the process of the reception of hotels in Izmir. Some basic principles had obviously been taken into consideration while getting some of the residences ready to serve for hostelry purposes. The most characteristic ones aside, the hotels with different plan schemes are treated in a separate category in this article. Each and every hotel in this category reflects different architectural features. Yet, it is still possible to state that those hotels also were built on a plan that had taken much from contemporary notions like functionality, setup of the space and programming. Some hotels, popular in their own right, yet with unknown plan schemes and typologies will be dealt with in another group.

3.1. Passaged Hotels

Centre-Passaged Hotels: Commune, Edremit, Egypte, Elphiniki, Epire, Grand Huck (previous M.Mille and Deux Augustes) and Kraemer Palace; Side-Passaged Hotels: Ioannina, Londres, Macedoine, Roumelie and the one next to the Russian Post Office.

|

The hotels with passages, all dating from the 19th century, were built on the First and Second Cordon Avenues (in other words: the Quay and the Parallel Street). Since the plots on the waterfront tended to be expensive, the most effective way to make use of the plot setups on the Quay was to build as many hotels possible in a side-by-side fashion, with the narrower front of the hotel facing the sea as opposed to a wider front facing the side street, so as to render all the buildings suitable for enjoying the sea view somehow. That premise in particular had entailed the planning of hotels with passages. And in that way, the hotels connected to the back and front streets from both ends and through a passageway lying between the two streets and crossing the hotel on the ground floor and this passage placed in the hotel and accessible from both ends had provided such hotels with their most characteristic planning feature of all. While such a passage was not open to public use, it would manifest a state of circulation that was controlled within the space between the opposite ends. A setup with a ground-floor passage in the mid axis of the hotel was labelled scheme with middle passage, whereas a setup with a passage lying along any of the four sides of the hotel was called scheme with side passage. Since the hotels with side passages were built on narrower plots in comparison to the hotels with middle passages, their plans (i.e. programming) were limited in terms of allowances.

|

In addition to passages, ground floors embodied also cafés, bars, restaurants, stores, depots, and of course, the halls of the hotels. Cafés and restaurants would preferably situate on the seafront and the happenings in such spaces would often spill over to the street making such places a natural extension of the vivid scene of the Quay. Centre-passaged hotels like Commune, Elphiniki and Kraemer Palace were neighbours with cafés, bars and restaurants. For instance, on the right of the entrance to Hotel Elphiniki there was a café, and on the left, a restaurant/bar. Hotel Kraemer Palace was a socially frequented place thanks to its famous restaurant/bar and the Hellenic Club located in a top floor. For the port was in short distance, plots on the seaside held high commercial value and the ground floors of many hotels were thus used partly for commercial purposes by stores and offices. Being adjacent to hotels as part of the same building, such commercial units did not necessarily have direct relations with the former, yet sometimes they were used by the customers of the hotels as well. Since the seaside was an urban area designed mainly for public entertaining and relaxing, stores and offices mostly situated on the facets of the buildings that looked either to the Second Cordon Street, or opened to passages. There were various commercial activities conducted in the area. On the ground floor of Hotel Kraemer Palace, for instance, there was a store specialised in supplies for the ships like food etc. Right next to the entrance of Hotel Commune, there was a grocery store, and a printing house downstairs Hotel Epire facing the Second Cordon Street. Furthermore, there were post offices downstairs Hotel Grand Huck and Hotel Londres.

|

Although there is no upstairs plan scheme of such hotels available to study, it is possible to figure out the spatial organisation of upper floors by looking at the documents we have of the ground floors of the same buildings. In such buildings, second storeys used to be reached by a stairway situated somewhere in the middle of the passage. In centre-passaged hotels, hotel rooms situated on two sides and opened to hallways (horizontally or vertically), and in side-passaged hotels, rooms and wet areas that opened to hallways had to be occupying only one side of the building. The buildings usually consisted of two or three storeys, and rarely of four storeys. Among centre-passaged hotels, Hotel Commune was a two-storey building and Hotel Edremit was another two-storey building yet accompanied with a mezzanine. While the hotels Egypte and Grand Huck were two-storey buildings previously, they were stretched to three storeys in due time. Likewise, Hotel Kraemer Palace was added a fourth floor. While the side-passaged hotel, Hotel Londres, comprised of a mezzanine over the ground floor, two additional floors and a partial roof floor; another hotel of the same type, Hotel Macedoine, was another two-storey building. The hotel located next to the Russian Post Office was later added an additional storey while it was originally a two-storey building.

|

The influence of Western architecture, particularly of Neoclassicism, can easily be traced in the facades of these hotels. By studying the photos of the centre-passaged hotels like Commune, Edremit, Egyote, Grand Huck and Kraemer Palace, and that of the side-passaged ones: Londres, Macedonie and the hotel near the Russian Post Office, the following facts could be concluded as the premises these hotels were built on:

|

- Emphasis on the passage, and therefore, highlighting the frontal position of the central axis in centre-passaged hotels,

- Emphasis on symmetry,

- Defining mouldings between storeys

- Utmost protrusion of the ground floor,

- Outward stretching of the building by means of balconies and oriels, especially along the central axis,

- Use of building elements like pediments, plasters and portals, as well as figurative ornaments like reliefs,

- Portal-shaped doors with circular arches and various types of windows including rectangular-shaped ones, the ones with jambs, and semi-circle and low arches,

- Facades with a tall parapet or pediment along the edge of the roof, or both of them applied together,

- Sign of the hotel over a parapet, pediment or balcony, or hanging somewhere up on the front facade in big letters.

3.2. Side Entrance Hotels

Hotels Alexandrie, Anatolie, Constantinople, Ile Metelin and Lespos et Kidonie.

Just like passaged hotels, the side entrance hotels of Izmir date from the 19th century. Yet, unlike passaged hotels, side entrance hotels situated on the corner lots where the First and Second Cordon Streets intersected and thus created narrow side streets. In this way, such hotels, being adjacent to the next lot, could front the two avenues and a side street as well. An exceptional case was that of Hotel Ile Metelin, in which the hotel, still located on a corner lot, was built in an only-adjacent range and the largest facade of the building faced the First Cordon Street - the waterfront.

As the name of this category implies, entrance to such hotels was accessed from the side of the hotel. In such hotels, the hall and stairs situated against the entrance, whereas the cafés would overlook the bay and the restaurants would be located in a fashion to face either the First or the Second Cordon Streets. Hotel Ile Metelin, with its large facade to the seaside, enjoyed a close proximity to the Quay together with the cafés and restaurant/bars which shared the facade. There were other commercial units on the ground floor as well. Along the longest sides of the hotels Anatolie, Alexandrie and Constantinople, on both sides of the entrances, there were stores, as well as between the café and the restaurant down Hotel Ile Metelin, and along the ground floor of Hotel Lespos et Kidonie looking to the Second Cordon Street - the Parallel Street.

|

We only have an image of Hotel Alexandrie out of the hotels of this sort. This hotel had featured a mezzanine over its ground floor and two floors more above that. The building had enjoyed a symmetrical facade pattern with defining mouldings between storeys, utmost protrusion of the ground floor, a corbelled balcony on the facade and other features such as pediment, plaster and portal, as well as the crowning of the hotel with pediment, and the hotels sign placed over the highest balcony, and in this respect, shared similar principles with the passaged hotels of Izmir.

3.3. Hotels with a Courtyard

Hotels Ekmekçibaşı, Evliyazade, Gaffarzade, Güzel İzmir, Hacı Ali Paşa, Hacı Hasan (Yeni Şükran), Hacı Sadullah, Kemahlı (Kemahlı İbrahim Bey), Meserret and Ragıp Paşa.

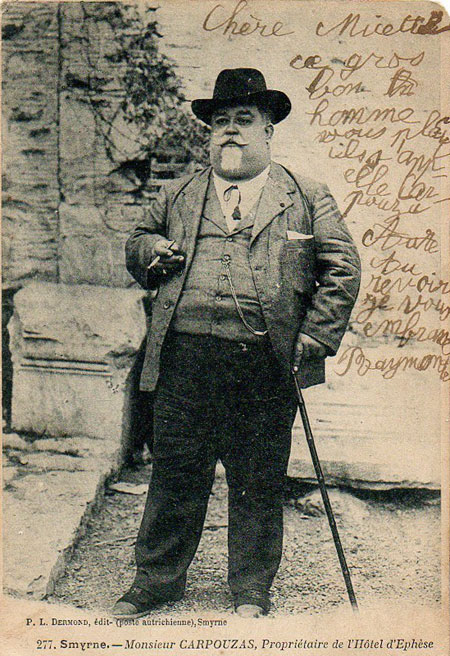

The hotels with their own courtyard concentrating in Kemeraltı10 date from the first quarter of the 20th century. The earliest examples of this category date to the second half of the 19th century and are otherwise called Early Kemeraltı Hotels with their khan-meets-hotel figure. During the period in question the area was not familiar yet with the concept of lodging in the sense of hotel type of accommodation, so some of the inns, traditionally known as khan but not exactly the khans built for trading or storing purposes, used to serve as hostelries. The scheme plans of these buildings were the same with that of the future hotels built in the area. Early Kemeraltı Hotels, just like the subsequent hotels, had a plan scheme that involved a courtyard, as well as a coffeehouse or a grocery store on any side of the entrance facade, a barn on one corner in the courtyard and sometimes a water supply inside the yard. The two Yusufoğlu Khans, seen to be standing side by side in the 1905 Insurance Plan, set an example to the inns in the area that exemplify the difference between commercial and lodging uses of khans. While the first Yusufoğlu Khan, the place of which was later to be occupied by Hotel Güzel Izmir built with the same plan, was a typical hostelry building with its courtyard setting, coffee shops and groceries on both sides and a water supply in the middle of the yard, the other one in commercial use, enjoyed a more compact spatial organisation than the former one. Throughout the first quarter of the 20th century, parcels of such transition period buildings were replaced by hotels (labelled as such, for that matter) with the same names as before and adhering to the former plan schemes. A few examples are the former Ekmekçi Khan and the latter Hotel Ekmekçibaşı, the former Evliyazade Khan and the latter Hotel Evliyazade, and the former Hacı Sadullah Khan and the latter Hotel Hacı Sadullah. This proves that hotel, as an establishment, was well received in Kemeraltı by then.

The hotels with courtyards had been lined up mainly along the Hükümet Avenue11. Unlike the First Cordon Street where Western culture dominated, around the bazaar, the carrying out of traditional commercial activities was the determinant of daily life. The majority of the customers of Kemeraltı hotels comprised of regional merchants who happened to visit Izmir. Such hotels, just like khans, had accorded themselves to the unsteady plot order of Kemeraltı. Since there were a limited number of plots in the area that face any street, the front facades of the buildings had to be kept as narrow as possible. Whereas in courtyards, it was aimed to create a quiet, shadowy indoor space isolated from the hurly burly of the street, and enhance the number of facade areas. This had fostered the degree of interior-exterior space relations in such hotels, unlike in khans. The hotels Ekmekçibaşı, Yeni Şükran and Kemahlı had second entrances on a side street narrower than the main one. Sites like coffee houses and diners which were frequented by hotel customers as much as townspeople also enabled the opening of the hotels to the outside world.

Spatial organisation in hotels with courtyards was quite similar to that in khans. Such hotels used to be composed of a set of places surrounding a courtyard and an upper storey formed in a likely fashion. Two-storey solutions were quite common. Sometimes mezzanines floors were used, as in the hotels of Kemahlı and Ragıp Paşa. The ground and second floors in such hotels used to serve either together or separately. Grounds floors were often occupied by coffee houses, diners, barns, stores, depots, and the entrance halls of the hotels including the stairs to upstairs. Coffee houses, as a typical feature to be found in such hotels, were often located next to the entrance of the courtyard. Such coffee houses portraying customers with their hubble-bubble pipes having coffee, tea or soft drinks were quite different than the hotel cafés of the Quay, and played a major role in the Turkish social and cultural lifestyle. Sometimes there were diners neighbouring hotels. The most known of all was Şükran Restaurant which was open until recent times. Commercial units in such hotel complexes used to serve independently of the hotels and were often small shops and offices accessed either from inside or from outside the courtyard. To give a few examples: the famous pharmacy Şifa had occupied the ground floor of Hotel Ragıp Paşa partly, and there was a grocers on the front facade of Hotel Güzel İzmir. The upper floor was made up of rooms that usually opened to a side or a middle hallway and sometimes into a sofa, and of wet areas.

Courtyard facades had flourished together with street fronts which were limited in size in hotels with courtyard. The generally narrow front facades of such hotels were set in line with the following premises:

- Emphasis on symmetry,

- Entrance of the courtyard emphasised with a portal or an arch,

- Separation of storeys with mouldings,

- Characteristic use of balcony and rarely of oriel whereby a corbelled feature is obtained,

- Grouted brick or stone masonry structure of particularly the upper storey facades,

- Wide-arched, large spaces in ground floors, and narrower, sometimes rectangular-jamb, circular or low-arched windows at upper floors,

- Usage of construction materials like wrought iron, plaster and relieves,

- Building endings in the fashion of a pediment, or a thick layer of moulding between the roof and the wall.

Courtyard facades resembled entrances facades in terms of the form of spaces and covering etc., but can be exposed to various features depending on the inner space. Among these features, we can name a routine, symmetrical order of a group of doors and windows, mouldings in between storeys, porticos, a finishing moulding or fringe towards the top edge of the building.

3.4. Hotels Converted From Houses into Hotels

Hotels Büyük Abdülkadir Paşa, Naim Palas, Sadık Bey (Yeni Sadık Bey), Zevk-i Selim, Tevfik Paşa.

This group of hotels were actually big houses later converted to hotels during the first quarter of the 20th century when hotels had already become popular and indispensable places, some of which do not exist currently. One of them, a hotel where several statesmen including Atatürk had stayed, Hotel Naim Palas on the Quay, actually serves as a museum. In the same vein, there is also Hotel Sadık Bey which was expanded with an extension of a modern building towards Basmane Square and Hotel Tevfik Paşa - both serve the same function still.

Conversion of houses into hotels was actually a phenomenon that lasted long. The Hotels Street (1296 Street) is an interesting example of this, on which former houses are being used as hotels. It is thought that the beginning of the employment and development of this street as a street of only hotels dates back to the establishment of Hotel Sadık Bey. Being an impetus for the enhancement of such conversions, this particular hotel led to the emergence and rise of Basmane district as a Zone of Hotels which has continued until today.

3.5. Hotels with Different Plan Schemes

The hotels with different plan schemes of the 19th century: Astre dAnatolie, Concorde, Leonidas, Ville and the hotels with different plan schemes of the 20th century: Ankara Palas, Cihan Palas (Emniyet), Aydın-Kasaba (Huzur), Bahçeli, Ege Palas and İzmir Palas.

It is certain that there have been a few lodgings with different solutions of planning that dated to the 19th century when characteristic types of hotels were born. As far as is known, Hotel Astre dAnatolie had situated on the Osmaniye Street, Hotel Concorde on the First Cordon Street, Hotel Leonidas on the English Pier Street, and Hotel Ville on the Second Cordon Street. We actually do not have much information about these hotels. However, it is likely to think of them as hotels shaped under Western influence if the data concerning their urban location, constructional program and names is to be considered in tandem with the conditions of the era.

|

Such hotels built in the 20th century in this category had high standards. They were built on relatively large plots. Even in such hotels, one could find that there was not certain integrity between the grounds floors and upper floors. Ground floors were often occupied, in addition to hotel halls, by cafés, patisseries and other commercial units that were not in direct relation with the hotel, and upper floors consisted of rooms and wet areas. While Hotel Aydın-Kasaba (Huzur) was a two-storey building, the old Hotel Ankara Palas was originally a two-storey building and later added a third one. Hotel Cihan Palas (Emniyet), for instance, was a heavy building with around 50 rooms, courtyards, strong rooms and a stone masonry facade. The now non-existent Hotel Ege Palas was a three-storey building. Hotel Izmir Palas was originally a two-storey building with a mezzanine storey. The hotels of Ankara Palas, Ege Palas and Izmir Palas were a few of the most sophisticated hotels at their time.

3.6. Hotels with Unknown Typology

Hotels with unknown typology of the 19th century: Europe, Great Smyrna, Mille, Orient, Royal Navy and the hotels with unknown typology of the 20th century: Anadolu, Asya (First Cordon Street), Asya (Kemeraltı), Ardahan, Balıkesir, Central (Merkez), Cihan, Cumhuriyet, Ferah Pension and Şerif Paşa Istanbul, Hacı Saadeddin, Halk, Mesut, Selçuk, Şark, Uşak, Yeni Anadolu, Yeni İzmir and Yeni Zafer.

The 19th century hotels with unknown typologies rank among the oldest hotels in the city and used to be located largely on the Frank Street. The data on these hotels reflect that they were Western-style hotels. The 20th century hotels of this type, on the other hand, were owned by Turks and run in the quarters of Kemeraltı, Basmahane, Tilkilik and Keçeciler. Chances are a certain number of them were hotels converted from houses. One of them, the Central Hotel, is known to be famous for its distinguished services.

Izmir, along with Istanbul, played an important part in the evolution of accommodation and lodging architecture in the Ottoman Empire. However, unfortunately, many of such hotels ceased to exist due to the fire of 1922 and the deliberate interventions the most of which were projected for getting unearned income in the following period. Consequently, a limited number of hotels of the 65 hotels listed above managed to remain standing. An important point worth making at this point is that a big part of the historical significance of the city of Izmir had vanished and been long forgotten with the disappearing of such hotels. This article, therefore, aims at revealing the fact that the city in itself played a historical role in the process of transformation of this type of buildings, as much as compiling the data regarding the Izmir hotels, including what is left of them, before they sink into oblivion.

|

Almanach Synoptıque A LUsage Du Levant, 1894.

Cuinet, Vital. (1894). La Turquie dAsie III. Paris: Librairie Felix Alcan.

Georgiades, D. (1885). Smyrne et LAsie Mineure. Paris: Imprimerie et Librairie Centrales des Chemins de Fer.

Goad, E. (1905). Plan dAssurance de Smyrne. London.

Karal, E.Z. (1983). Osmanlı Tarihi V. Cilt Nizam-ı Cedit ve Tanzimat Devirleri (1789-1856). Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu Basımevi.

Kayın, Emel. (1998). Historical Evolution of Hostelry Buildings with Particular Reference to Those within the Inner-city of İzmir from the 17th to the First Quarter of the 20th Centuries (Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis). Izmir: Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences of Dokuz Eylül University Architectural Design Program.

Kayın, Emel. (2000). İzmir Oteller Tarihi, İzmir: İzmir Büyükşehir Belediyesi Kent Kitaplığı.

Kıray, Mübeccel. (1972). Örgütleşemeyen Kent. Ankara: Türk Sosyal Bilimler Derneği.

Kütükoğlu, Mübahat. (1985). Türk-İngiliz İlişkileri 1583-1984. 1838 Osmanlı-İngiliz Ticaret Muahedesi. Ankara: Başbakanlık Basın Yayın ve Enformasyon Genel Müdürlüğü. s.53-60.

Rougon, F. (1892). Smyrne. Paris: Berger-Levrault et Cie.

Scherzer, C. de. (1873). La Province de Smyrne. Vienna: Librairie Universitaire de Beck.

2 Associate Professor, Department of Architecture, 9 Eylül University.

3 gorkemdaskan[at]gmail.com.

4 Kıray, 1972, p.11-12.

5 Karal, 1983, p.260-262; Kütükoğlu, 1985, p.53-60.

6 Rougon, 1892, p.145-149; Georgiades, 1885, p.154-163.

7 Scherzer, 1873, p.40; Georgiades, 1885, p.94.

8 Cuinet, 1894, p.465-468.

9 Kayın, 2000; Kayın, 1998.

10 TN. The historical bazaar district of the city.

11 TN. Present-day Anafartalar Avenue.