Introduction

I am taking the liberty to introduce the research project that has fascinated fellow art-historian Flavia Nessi-Yazitzoglou and myself, and on which we are currently preparing a catalogue and temporary exhibition at the Benaki Museum, Athens, scheduled to open in autumn 2013.

Our research focuses on 19th century painted metal trays from important private and museum collections in Greece and Turkey. Vastly under-studied, these objects are familiar objects with unfamiliar (hi)stories, in both countries. In Greece they are considered ‘Greek folk art’, while neither term accurately describes them. In Turkey they are known as ‘pulat tepsi’, which is equally misleading. Where did these objects come from, who made them and for what market? Where they small luxuries or inexpensive trifles- to be used or displayed, do they reflect an ‘eastern’ or western taste? How did they fit into the rituals of daily life in this part of the world? What could their iconography have meant to their audience? Mostly painted with scenes of Constantinople, images of beautiful women, portraits of actresses and royals, decorative motifs of fruit and flowers, the painted trays are products of a fascinating era – they represent the boom of industrialization, and were made to be sold in a region marked by potent historical and social change, as the Ottoman empire struggled between traditionalism and ‘modernity’, before being finally dissolved by the dawn of nationalism(s) and the beginning of a new (nationalistic) order in the region.

As little research has been done on these objects, any information on the socio-cultural and art-historical milieu that produced them would be extremely valuable in addressing a series of as yet unanswered questions; from the (Levantine?) artists who may have painted them (or alternatively for the ‘mixed-media’ trays which were part-painting and part-lithography or chromolithography, evidence of printer’s workshops where they may have been produced), the merchants who may have imported and sold them, references to everyday life that may mention such objects in use in contemporary households in any source (from memoirs to narratives, inventories or wills) to name but a few. In the attachment, we have taken the liberty to put down some of our ideas and questions. Any thoughts or contributions you may have would be greatly valued, and would of course be suitably credited both in the publication and the exhibition. We would also be very interested in hearing about private or museum collections that we have not yet seen.

Imported or Locally produced? Places of Production and Dating

Dating: The trays were produced in the 19th and at the latest in the early 20th century. The earliest examples appear to date from c.1830s, while the majority of works seem to date towards the end of the century. This means they date at the end of the boom for Japanese wares in Europe, when the trade in such wares was waning. (Pontypool for instance halted production in 1812).

Imports / Possible places of production: Britain held the monopoly of exports, even exporting the raw material (tin) to other production centres (ie. Germany). British-made trays are found in Greek collections. ‘Blank trays’ produced in the Midlands (Wolverhampton, Birmingham, Bilston) were sold extensively both in the UK and abroad, suggesting that the trays could also have been produced in the UK and painted elsewhere. Germany is also a likely source: continuing political link with the region is noted (King Otto and his court/ Athens-Munich), also the presence of stamped Braunschweig products in Greek collections. Russia is also a possibility - trading links in the region led to other Russian artefacts finding their way into the local market, but the aesthetics of Russian lacquered objects are very different.

The Case for a Local Production:

• An existing tradition of lacquering in the Ottoman Empire.

• In the age of the Great Exhibitions (ie. London, 1851) – the easy dissemination of models, ideas, achievements in industrial production.

• The role of Aegean islands such as Chios and Mytilene as major trading stops between Europe and the coastal cities of Asia Minor, where goods were unloaded and stored, possibly ‘finished’ by local craftsmen in a fashion suited to local tastes, before being shipped to their final destination.

• The existence of a trade in ‘blank’ pieces underlines the possibility that the trays could have been produced abroad and painted locally.

• The techniques could have been executed locally, and manufactured even at a modest scale (without necessitating large-scale industrialization). For instance, printers involved in litho productions in Constantinople and Smyrna.

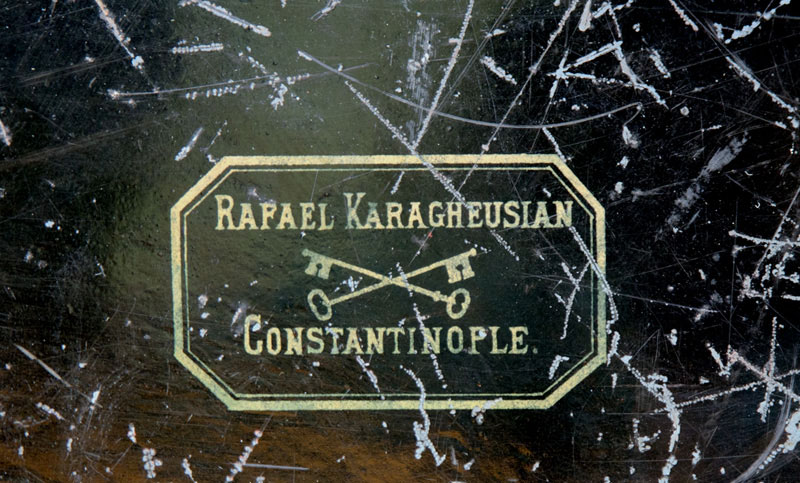

• The role of powerful mercantile elites resident in centres such as Constantinople and Smyrna etc. –the parallel with the ceramic industry (merchants in Syros sending designs to producers in England and Scotland and importing the final product). Also stamps/ markings on the trays lead to Galata and Pera, the international quarter of Constantinople, where they appear to have been bought and sold in shops specializing in household wares– for instance:

LEVI ET COHEN (specialising in Household wares)

18 Sultan Hamam Str., Constantinople

CZERNAY et Cie (specialising in crystal and porcelain)

5 Kerestedji Str., Galata

48 Yeni Djami Str., Galata

Home addres: Baghtch Str., Ferikoy

NISSIM CORONIO (specialising in crockery and glassware) 55 Yeni Djami Str. Galata

(Information from the Annuaire Oriental du Commerci de l’ Industrie de l’Administration et de la Magistrature 9me Anne 1889-90 CERVATI FRERES & Cie – Costantinople).

On the map

Where have they been found so far: besides Athens and Istanbul in the Aegean (Mytiline, Syros, Mykonos, Spetses, Ydra) but also the Ionian (Corfu), Northern Greece (Kastoria) and the Peloponnese (Leonidio).

Iconography: Scenic Views, Female Beauties, Politics and Kings

The evidence of the iconography / Identifiable models and sources (i.e. photography and prints)

a) Views/Cityscapes: mostly of Constantinople (using also familiar prints by Allom and Bartlett etc.) – but also of other cities – are a theme popular in wall painting throughout the region, as much in Greece as in Turkey. Views also include European capitals: Paris, Dresden, Venice. Iconographically this interest in landscape vignettes is closely linked to mural painting in this period found as much in the Palaces of Istanbul to important dwellings in both Greece and Turkey.

b) Female portraits: the vast numbers of trays including representations of the human figure suggest that at least these pieces were not sold to a Muslim audience but, possibly to a Levantine market.

c) Royal Portraits / Portraits of Contemporary Figures: Images of Greek Kings and Queens on the other hand suggest that this particular group of objects were produced not only specifically ‘Greek’ but also for an audience that that was politically aware. There are numerous objects that reflect the unsettled age of conflict in the Balkans – the Balkan wars (war heroes like Smolensky, but also ‘Bulgaria leading the People etc.’). There is also imagery of the Russian royalty, namely Tsar Alexander III Maria Fyodorovna / the Empress Sisi / trays with military figures etc.

d) Still-life imagery: flowers, fruit, musical instruments and smoking paraphernalia (pipes etc.).

e) Other themes: architectural vignettes (Turkish/oriental subject-matter including tents and landmarks), chinoiseries, ‘alpine’ vignettes, scenes inspired by the history of art (including allegorical and mythological scenes).

Overall, iconography is puzzling with regard to the intended audience of the works – some are ‘western’, others are western with an orientalising viewpoint (reflecting a western view of ‘the orient’), others appear to cater for a Muslim audience (i.e. human figures removed from a recognizable topographical view).

Materials and Techniques

We have not had the chance to do a chemical examination of the works – however they can be variously described as ‘japanned ware’ or ‘tole peinte’. Some of the trays are painted, others are produced using a combination of painted / stenciled / printed elements (chromolithography or lithography), others still including decalcomanias. There seems to be a line of evolution, from the hand-painted pieces to those who use the ‘modern’ techniques, typical of the passion of the age for the mechanical reproduction of images. That said, some of the earliest securely dated examples are produced using a printing technique (lithography). Overall, the works represent the transition from pre-industrial to industrial, and they seem to have been intended to evoke an aesthetic of ‘modernity’ (the fact that the handles are not soldiered on to the trays but rather affixed with large, obvious bolts suggests that their aesthetic is provocatively modern).

Products for the middle Class

A middle class market is in evidence, hence their disappearance when silver-plating makes another form of luxury affordable. There is also a sense that the works decline in importance – presumably from an object intended for the affluent upper-middle class to something suited for the petite bourgeoisie when they begin to be produced in greater quantity. Interviews with collectors place the objects in the homes of the upper/ middle- class families (merchants, notaries, etc.).

Use and function

The trays were clearly functional objects, but were also probably also valued for their beauty and displayed in a prominent position when not in use. Marks of use suggest they were used as serving trays for tea and coffee, probably also the ‘glyko tou koutaliou’ (syrupy desert taken on a spoon, with a glass of water), or some alcoholic beverage. There is visual evidence to support this in period illustrations.

There are also a number of large, round painted trays which were clearly used as tables.

The end of the story

Printed tin in full colour and the economical silver-plated wares that offered a greater ‘feel for luxury’ at a fraction of the cost put an end to this first semi-industrialised production of painted trays. Nonetheless, at least in Greece, the love for such objects brought about the survival of the genre into something epitomizing ‘Greekness’, and ‘traditionalism’, taken over by artists such as Bost, Spyros Vasileiou and others.

Dr. Myrto Hatzaki studied art history at Warwick University and the Courtauld Institute of Art – a Byzantinist at heart, she is curator of temporary exhibitions in the field of the applied and decorative arts at the ILJM in Athens. Her book Beauty and the Male Body in Byzantium: Perceptions and Representations in Art and Text was published in 2009 by Palgrave Macmillan.

The two have collaborated recently in the exhibition Boîtes de Luxe: French 19th century boxes from the Collection of Janine Nessi- Parmentier at the ILJM (October 2009 - Febuary 2010).

2- If you have information to assist the research of Dr. Myrto Hatzaki and Flavia Nessi Yazitzoglou please contact them on myrtohat[at]gmail.com and flavianessi[at]gmail.com.

|

|

|

|

|