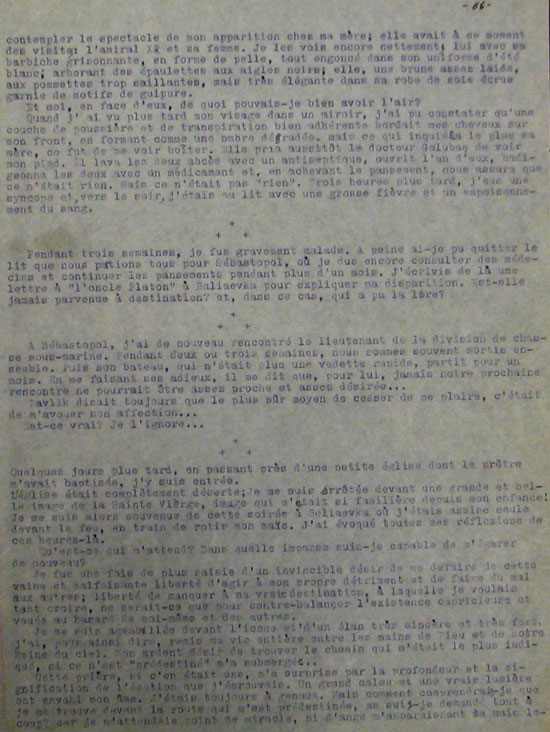

L’anneau d’argent [Silver ring] - 1914 - 1917 - 1920 - Iraïda Barry (née Kedrina) - memoirs

unpublished memoirs held at the School of Slavonic and East European Studies, London

Transcription of the last 2 pages:

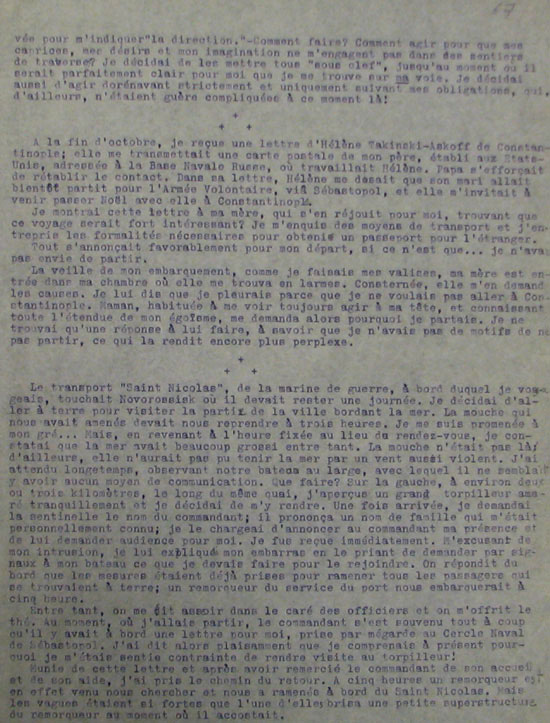

La lettre qui me parvenait de si étrange façon était du jeune frère de Pavlik ; il se battait alors dans les rangs de la III-me division de la garde. Sa lettre révélait un état de fatigue et de dépression et une incapacité de trouver consolation et apaisement.

Tout le reste peut être narré brièvement.

Ma rencontre avec la famille Askoff fut un sujet de grande joie. La ville de Constantinople me sembla très intéressante, bien que les quartiers européens m’aient frappée par l’étroitesse des rues et leur saleté. Au début, je me suis beaucoup promenée et j’ai visité les endroits les plus remarquables. Plus tard, j’ai remplacé Hélène à la Base Navale Russe; son mari était tombé malade à Sébastopol et elle était partie pour le soigner. Trois mois après, elle revint veuve. Je lui ai naturellement restitué sa place et j’en ai cherché et trouvé une autre.

Retourner en Russie ? je n’en avais pas l’intention, d’autant que je savais par les lettres de ma mère, que la situation de l’armée blanche n’était pas très solide. Quant aux Mouravieff , père et fils, ils étaient en train d’organiser une compagnie de navigation et espéraient arriver prochainement à Constantinople où ils comptaient établir une agence.

Je continuai donc à ‘tenir sous clef’ mon imagination et mes désirs. De temps à autre, je m’observais moi-même curieusement, essayant de deviner si ma vie avait commencé à sa ‘véritable’ direction.

Au cours de l’année 1920, je fis trois rencontres mémorable: le lieutenant de la division de chasse sous-marine arriva à Constantinople, à bord d’un troisième bateau et me demanda en mariage; à son grand étonnement, comme d’ailleurs au mien, je déclinai sa proposition. Deux nouvelles figures parurent ensuite à mon horizon; toutes deux étaient jeunes et sympathiques; je comprenais fort bien que, si mon imagination n’avait pas été enfermée et verrouillée, ces deux rencontres auraient donné lieu à de nouvelles mises en scène.

Vers la fin de l’été, je me rendis compte que l’une de ces deux personnes était très persévérante et finirait peut-être par me persuader de l’épouser.

Entre temps, au cours de cette guerre fratricide, la situation au front ne semblait guère favorable pour l’armée blanche. Les circonstances générales ne permettaient pas aux Mouravieff d’achever l’organisation de leur entreprise. Sur quoi le mari de ma mère tomba gravement malade d’une fièvre typhoïde récurrente. Je fus chargée d’acheter à Constantinople les médicaments introuvables à Sébastopol; je parvins à prendre un mois de congé et j’apportai moi-même les médicaments. Sébastopol semblait un camp mi-civil, mi-militaire; on sentait venir du Nord de lourdes nuées…

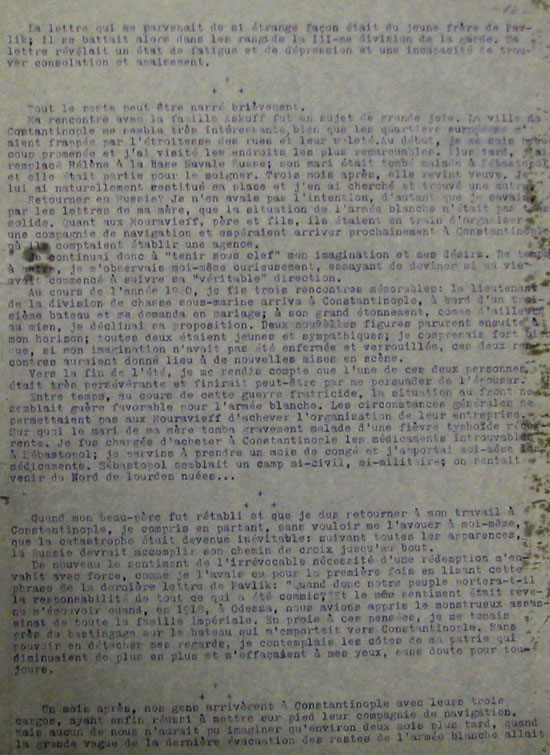

Quand mon beau-père fut rétabli et que je dus retourner à mon travail à Constantinople, je compris en partant, sans vouloir me l’avouer à moi-même, que la catastrophe était devenue inévitable: suivant toutes les apparences, la Russie devrait accomplir son chemin de croix jusqu’au bout.

De nouveau le sentiment de l’irrévocable nécessité d’une rédemption m’envahit avec force, comme je l’avais eu pour la première fois en lisant cette phrase de la dernière lettre de Pavlik: ‘Quand donc notre peuple portera-t-il la responsabilité de tous ce qui a été commis?’ Et le même sentiment était revenu m’émouvoir quand, en 1918, à Odessa, nous avions appris le monstrueux assassinat de toute la famille impériale. En proie à ces pensées, je me tenais près du bastingage sur le bateau qui m’emportait vers Constantinople. Sans pouvoir en détacher mes regards, je contemplais les côtes de ma patrie qui diminuaient de plus en plus et s’effaçaient à mes yeux, sans doute pour toujours.

Un mois après, nos gens arrivèrent à Constantinople avec leurs trois cargos, ayant enfin réussi à mettre sur pied leur compagnie de navigation. Mais aucun de nous n’aurait pu imaginer qu’environ deux mois plus tard, quand la grande vague de la dernière évacuation des restes de l’armée blanche allait déferler sur Constantinople, ‘on’ ferait en sorte d’enlever des mains des nôtes leurs fameux bateau et qu’eux-mêmes se trouveraient à terre comme de simples refugiés.

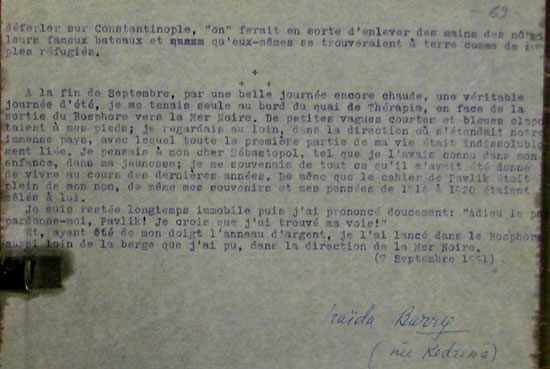

A la fin de Septembre, par une belle journée encore chaude, une véritable journée d’été, je me tenais seule au bord du quai de Thérapia, en face de la sortie du Bosphore vers la Mer Noire. De petites vagues courtes et bleues clapotaient à mes pieds; je regardais au loin, dans la direction où s’étendait notre immense pays, avec lequel toute la première partie de ma vie était indissolublement liée. Je pensais à mon cher Sébastopol, tel que je l’avais connu dans mon enfance, dans ma jeunesse; je me souvenais de tout ce qu’il m’avait été donne de vivre au cours des dernières années. De même que le cahier de Pavlik était plein de mon nom, de même mes souvenirs et mes pensées de 1914 à 1920 étaient mêlés à lui.

Je suis restée longtemps immobile puis j’ai prononcé doucement: ‘Adieu le passe pardonne-moi, Pavlik! Je crois que j’ai trouvé ma voie!’

Et, ayant été de mon doigt l’anneau d’argent, je l’ai lancé dans le Bosphore aussi loin de la berge que j’ai pu, dans la direction de la Mer Noire.

(7 Septembre 1951)

Iraïda Barry (née Kedrina)

translation to English

The letter that reached me in such a strange way was from the younger brother of Pavlik; he fought in the ranks of the IIIth Guard Division. His letter revealed a state of fatigue and depression and an inability to find solace and peace.

Everything else can be briefly narrated.

My meeting with the Askoff family was a matter of great joy. The city of Constantinople seemed very interesting, although the European quarters have struck me by the narrowness of the streets and dirt. At first, I walked a lot and visited some of the most remarkable areas. Later, I placed Helen in the Russian naval base, her husband had fallen ill in Sevastopol and she had departed to treat him. Three months later, she returned a widow. I naturally replaced her position by seeking and finding a replacement.

Return to Russia? I had no intention, especially since I knew from the letters of my mother, that the situation of the White Army was not very strong. As for Mouravieff, father and son, they were organizing a shipping company and hoped to arrive soon to Constantinople where they intended to establish an agency.

So I continued to ‘keep under lock and key’ my imagination and my desires. From time to time, I was observing myself curiously, trying to guess if my life had begun its ‘real’ direction.

During the year 1920, I had three memorable meetings: the lieutenant of the division of the anti-submarine patrol arrived in Constantinople, on board a third boat and asked me to marry him, to his astonishment, and as before also mine, I declined his proposal. Two new faces appeared on my horizon, both were young and friendly and I understood very well that if my imagination had not been shut and locked, the two meetings would have resulted in new developments.

Towards the end of the summer, I realized that if one of these two people was very persistent he eventually perhaps persuade me to marry him.

Meanwhile, during the fratricidal war, the situation in the front did not seem favorable for the White Army. The general situation did not allow Mouravieff to complete the organization of their business. What is more the husband of my mother fell seriously ill with typhoid fever recurring. I was responsible for purchasing drugs in Constantinople not found in Sebastopol, I managed to take a month off and I brought myself the medicine. Sebastopol seemed like a half civilian, half military camp, one felt heavy clouds approach from the North ...

When my stepfather had recovered and I had to return to my work at Constantinople, I understood in parting, without wanting to admit it to myself, that the catastrophe was inevitable: according to all appearances, Russia should fulfill the Stations of the Cross until the end.

Again the sense of the irrevocable need for redemption came over me with strength, as I had first read this sentence from the last letter of Pavlik: ‘When will our people will hold the responsibility for all that has been committed?’ And the same feeling had come to move me when, in 1918, in Odessa, we learned of the monstrous murder of the whole of the imperial family. Plagued by these thoughts, I stood near the railing on the ship that carried me to Constantinople. Without being able to tear my eyes, I watched the shores of my country that increasingly diminished and faded for me, probably forever.

A month later, our people came to Constantinople with their three freighters, having finally managed to set up their shipping company. But none of us could have imagined that about two months later, when the great wave of the final disposal of the remains of the White Army would sweep over Constantinople, ‘they’ would remove from our hands of their famous boat and leave them on shore as mere refugees.

At the end of September, on a beautiful still warm day, a real summers day, I stood alone at the edge of the dock in Therapia, opposite the exit of the Bosphorus to the Black Sea. Small waves, short and blue were lapping at my feet, I looked to the distance, in the direction where our great country stretched, with which the entire first part of my life was inextricably linked. I thought of my dear Sevastopol, as I had known in my childhood, in my youth, I remembered what it had given to me in my last years. At the same time the notebook of Pavlik was full of my name, and my memories and thoughts from 1914 to 1920 were mixed with his.

I stayed a long time motionless and then I pronounced softly ‘Farewell the past forgive me, Pavlik! I think I found my way!’

And, removing from my finger the silver ring, I threw it in the Bosphorus as far from the shore as I could, in the direction of the Black Sea.

(September 7, 1951)

Iraïda Barry (née Kedrina)

Türkçeye tercüme (son iki sayfa)

Elime bu kadar garip şekilde geçen mektup Pavlik’in genç kardeşinden gelmişti; III. Muhafız Birliği safhında savaşmıştı. Mektup yorgunluk ve depresyon halini, teselli ve huzur bulma acizliğini ortaya çıkartıyordu.

Geri kalan kısaca anlatılabilir.

Askoff ailesi ile buluşmam büyük bir seviç kaynağı oldu. Her ne kadar Avrupa Mahallesi sokaklarının darlığı ve kiriyle beni şaşırtmış olsa da İstanbul şehri çok ilgi çekici görünüyordu. İlk başlarda uzun yürüyüşlere çıkıp en dikkat çekici bölgelerini ziyaret ettim. Daha sonra Helen’i Rus deniz üssüne yerleştirdim, kocası Sevastopol’da hastalanmıştı ona bakabilmek için yola çıktı. Üç ay sonra bir dul olarak geri döndü. Doğal olarak onun boşluğunu doldurmak için kendisine bir aday buldum.

Rusya’ya geri dönmek? Hiç niyetim yoktu özellikle annemin mektubundan Beyaz Ordu’nun pek güçlü olmadığını öğrendikten sonra. Mouraviefflere gelince, baba ve oğul, bir denizcilik şirketi kuruyorlardı ve İstanbul’a bir an önce varıp acente açmak niyetindeydiler.

Böylece hayal gücümü ve arzularımı “kilit altında” tutmaya devam ettim. Zaman zaman kendimi ilgiyle gözlemledim, hayatımın gerçek amacına doğru gidip gitmediğimi tahmin etmeye çalıştım.

1920’de üç tane unutulmaz karşılaşma yaşadım: Denizaltı avcı devriye yüzbaşısı İstanbul’a gelmişti, güvertede bana evlenme teklif etti, teklifini reddettim, o da ben de şaşkınlığa uğradık. İki yeni sima görüş alanıma girdi, ikisi de genç ve sıcakkanlıydı, anladım ki hayal gücüm kapalı ve kilitli olmasaydı bu iki tanışma yeni gelişmelerle sonuçlanacaktı.

Yazın sonlarına doğru fark ettim ki bu iki kişiden biri ısrarcı olsaydı eninde sonunda beni evlenmeye ikna edebilirdi.

Bu arada kardeş ile kardeşin birbirini öldürdüğü savaş sırasında, Beyaz Ordu’nun cephedeki durumu pek avantajlı görünmüyordu. Genel durum Mouravieff’in iş organizasyonunu sonuçlandırmasına engel oldu. Dahası annemin kocası tekrarlanan tifodan ciddi şekilde hastalandı. Sevastopol’da bulunamayan ilaçları İstanbul’dan tedarik etmek benim görevimdi. Bir ay için yola çıkmayı başarıp ilaçları götürebildim. Sevastopol yarı sivil yarı askeri bir kamp gibi görünüyordu, Kuzey’den gelen kara bulutlar hissedilebiliyordu.

Üvey babam iyileştiği zaman İstanbul’a, işime geri dönmek zorunda kaldım. Ayrılırken anladım ki, her ne kadar kendime itiraf etmek istemesem de felaket kaçınılmazdı: Rusya bu zorlu ve engelli yolu tamamlamak zorundaydı.

Pavlik’in mektubunun ilk cümlesini okuduktan sonra yine o tanıdık his beni şiddetle sarstı: “İnsanlarımız ne zaman işlenen suçların sorumluluğunu alacak?” Aynı duyguyu 1918’de Odessa’da tüm kraliyet ailesinin cinayetini duyduğumda da hissetmiştim. Düşüncelerimden rahatsız olmuş bir biçimde beni İstanbul’a taşıyan geminin trabzanlarına tutundum. Gözyaşlarımı tutamadan, muhtemelen benim için sonsuza dek, giderek küçülen ve kaybolan yurdumun kıyılarını izledim.

Nihayet insanlarımız denizcilik şirketlerini kurabildi ve bir ay sonra üç kargo gemisi ile Istanbul’a geldiler. Fakat hiç birimiz bundan iki ay sonra Beyaz Ordu’nun kalıntılarının, nihayi bertaraf dalgası ile Istanbul’un üzerine çöküp onları elimizden alıp basit mülteciler gibi “meşhur” gemiden indirip, kıyıda bırakacaklarını tahmin edemezdik.

Eylül’ün sonlarına doğru, güzel ve halen ılık bir günde, gerçek bir yaz günü, Tarabya’da, Boğazın Karadeniz’e yöneldiği yönün karşısında, tek başıma rıhtımda durdum. Küçük dalgalar, kısa ve mavi, ayaklarıma çarpıyordu, uzaklara baktım, muazzam ülkemizin uzandığı, hayatımın ilk bölümünün tamamının ayrılmaz bir şekilde bağlı olduğu yöne. Sevgili Sevastopolumu düşündüm, çocukluğumda ve gençliğimde hatırladığım hali ile, bana son yıllarda verdiklerini düşündüm. Bu arada Pavlik’in defteri benim adım ile doluydu ve 1914 ile 1920 yılları arasındaki hatıralarım ve düşüncelerim onunkileriyle karışmıştı.

Uzun bir süre hareketsiz kaldım ve sonra usulca “Hoşça kal geçmiş, beni affet Pavlik! Galiba yolumu buldum” diye fısıldadım.

Ve, parmağımdan gümüş yüzüğü çıkarıp, kıyıdan olabildiğince uzağa, Karadeniz yönüne, Boğaza doğru fırlattım.

(7 Eylül 1951)

Iraïda Barry

Click here to return to the Barry family information page: |