Interview with Philip Mansel, on his book ‘Sultans in Splendour: Monarchs of the Middle East 1869-1945’ - Parkway Publishing, 1988

|

1- The book starts with vivid descriptions of the celebrations in Egypt in 1869 with the opening of the Suez Canal. The canal was dug by Egyptian labour, French knowhow and international finance. Do you think this marked a seminal moment for Egypt and the Middle East at large? The technological and organisational gap between the Levant and the West was now too big to bridge, the East couldn’t cope with the West militarily or economically from thence, so were the rules of the game permanently altered until the Nasser revolution?

Yes, I think that is completely correct and it facilitated transport and exchange of people enormously and amongst other things, it revolutionised the Hajj, it made it much easier to get to Mecca. For example pilgrims from Iran could now use the safer and lot quicker sea route via Trabzon or other ports that eventually linked to the Red Sea. And above all, it made it almost certain that Britain would grab Egypt, it made Egypt even more the route to India. Even back during the Indian mutiny Egypt was used as a conduit point to send reinforcement troops to the sub-continent. But other things like the creation of Alexandria and the laying of the Alexandria to Cairo railway were already opening up the Middle East and facilitating exchanges. But the financing of the Suez Canal revealed the folly and extravagance of the Khedive Ismail and the way he fell into debt and under the control of the international financiers. All reminiscent of many Western countries now.

2- The nationalistic revolutions that had the promise of liberation from tyranny in most cases have evolved in to tyrannies of dictators, whether Baath nationalists or Islamists. The Arab Spring is therefore the counter revolution to that. Why do you think it took so long, and do you think these revolutions could also be betrayed by their leaders in time?

As one serving British diplomat recently said to me all revolutions are betrayed. By definition they cannot live up to their citizens’ expectations. But I think there is some hope in Egypt and Tunisia, countries that have a Mediterranean as well as an Arab and Islamic identity. And they took so long because we in England luckily do not - yet - know the paralysing effect of police states, military regimes and fear of prison and torture.

3- Do you think Mohammed Ali, his successor Said Pasha and his successor Khedive Ismail were bound in their quest to free Egypt of Ottoman control to go for modernisation, and in so doing ironically placing their country in danger of increasing debt and British domination?

Yes, I think they were bound to and if the successors had been cleverer British military occupation might have been avoided, or lasted less long (1882-1956). One British official wrote that if the rulers of Egypt had been as sensible as Prince Omar Toussoun, there would have been no ‘Egyptian question’.

4- Would it be extreme to label the significant Levantine merchant community in Egypt and the Ottoman Empire a ‘fifth column’ in European diplomatic manoeuvrings, not by initial design but as a useful tool for foreign powers to use either to gain intelligence or to protect their co-religionists?

Yes, that is completely correct. Although Levantine schools and innovations could encourage local nationalism or progress, individual Levantines in many cases clearly wanted foreign occupation, both in Izmir and in Alexandria. In the latter city, local Greeks gave celebratory balls after the British invasion of 1882. Cavafy’s brothers complained that the British were not sufficiently ruthless in their punishment of Egyptians.

5- The subtitle of the book is ‘Monarchs of the Middle East’, yet amongst those featured are those of Central Asia. Is this because Islamic Central Asia is in your view a partial cultural continnder uation of Arabia?

I put them in because at that time (1988) those areas were under Soviet control. I wanted to remind readers that Bokhara and Kabul once modelled themselves on Istanbul. They were not part of Arabia and were, and again now are, part of the Islamic world.

6- Is it strange that even strong countries with a long serving ruler – for example Iran - also fell into the trap of relying on foreigners for investment, trade concessions and even military protection. Was their historical enmity to the Ottomans part of the reason?

I don’t think it was strange, look at the problems of Greece or Spain today, or the United States today, which also rely on foreign investors and foreign financial markets.

7- The Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamit’s reign is recorded in history as a whole series of negatives, including the use of Kurdish Hamidiye irregulars for atrocities against Armenians. However under him, despite the Caisse de la Dette, which was a vast European-run institution, there was confidence in the system, the government was able to raise new loans and unlike Egypt or Tunisia, this indebtedness never led to foreign control of government. Do you think it a shame the positives of Abdulhamit’s reign have long been over-shadowed with the darker side of his character and regime?

Yes, I would say we tend to forget how much it varied from province to province. Smyrna and Beirut for example experienced a golden age of economic growth and modernisation. By his standards he did his best. But by the end of his absolute rule he no longer had the money to pay his troops. So he wasn’t that much of a success.

8- Understandably the modern Republic of Turkey in its appraisal of history puts a positive spin on the achievements of the Committee of Union and Progress while denigrating the role and actions of the last few Sultans during the early 20th century. Only a few months after the Young Turk revolution in October 1908, Austria annexed Bosnia, followed by the Italian invasion of Libya, the Albanian revolt of 1912 and the first Balkan War in the same year. Do you think official history, even after all this time, needs to rebalance its examination of this disastrous period that was swaying between tyranny and liberalism, but the inexperienced foreign policy of the Young Turks clearly exacted a heavy price on the empire?

I think what is often forgotten are the close links of the CUP with revolutionaries of other nationalities, Greek, Albanian, Armenian. They were completely out of their depth in international diplomacy. Enver Pasha loved war, but was no good at waging it.

9- From the Arabi revolt of 1882 in Egypt and the British intervention it is clear the line of ruling Khedives became more and more impotent in the face of British imperial policy. Abbas Hilmi who reigned from 1892 seems to have been particularly talented yet hamstrung on all quarters. Do you think these Khedives could have played their cards differently to regain Egyptian independence?

No, I think they were more or less powerless. But King Fouad who ruled in 1917-36 did play a clever political game. He was a true Levantine as some of his contemporaries wrote. Expert at political and financial manoeuvres.

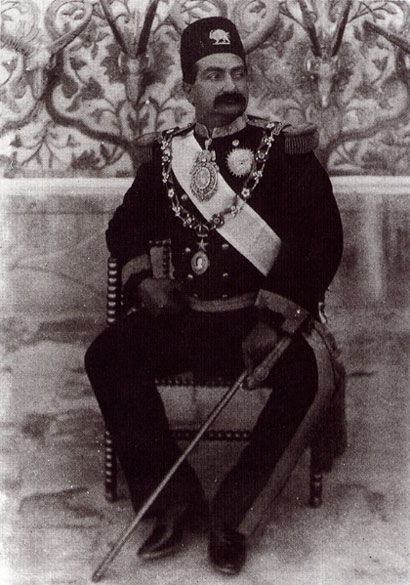

10- The book is richly illustrated with photographs of the various Sultans, Princes and Beys of the Middle East. Under strict Islamic interpretation all depictions of faces is considered ‘haram’. Yet some rulers such as Moulay Abdul-Aziz of Morocco practiced it with great enthusiasm. So bending the rules is clearly the prerogative of rulers. However do you think this double-edged sword of self-vanity and love of western innovations made these rulers less popular, weakening their power bases and thus helping the demise of their dynasties?

It is only one Islamic tradition against the representation of the human form. Think of Persian and Ottoman miniatures and Mogul portraits, and the cult of cinema and videos in the modern Middle East. Yes, I think probably the dynasties’ love of modern technology and the changes in their way of life did help to alienate their subjects, as happened with the last Shah of Iran who left in 1979.

11- By the treaty of Fez of 1912 with Morocco, France promised to protect ‘His Sherifian Majesty against all dangers which may threaten his person and his throne’ in return for the right to introduce the ‘administrative, judiciary, scholastic, economic, financial, military reforms which the French government will judge useful’. The Sultan (Moolay Hafid) was reduced to signing the decrees placed before him by the Resident General. Do you think the Sultan and his court fully realised they were giving up their independence when signing this treaty?

I am not certain, but probably they thought they did a good bargain against overwhelming odds. The Moroccan monarchy has lasted longer than the third French Republic which signed this treaty in 1912. Like all the French officers that went round in the 18th century predicting the imminent collapse of the Ottoman Empire but were themselves guillotined in the 1789 revolution.

12- Do you think the Victorians warped view of the moral decay and harem culture of the Middle East helped ease their conscience when they made their moves to colonise these lands.

No, they used real incidents and national conflicts. In some ways in my opinion, they did all too little to change the status of women or slaves. That has come subsequently from the local elites themselves. No Western power that I know of forbade polygamy, unlike for example Kemalist Turkey, and many other independent governments. I would like to say that collecting these photographs and interviewing survivors from these regimes was highly pleasurable. Local libraries in the 1980s were extremely helpful and I had the time of my life interviewing survivors from the reign of King Farouk in London and Paris, Cairo and Istanbul. They were extremely kind and hospitable and despite their years full of joie de vivre. They would have been delighted - and not at all surprised - by the Egyptian revolution of 2011. The tragedy for Egypt is that the politicians, there has been a too long a gap between 1952 and 2011. There are no politicians with experience for the upcoming free elections and party politics.

13- It is quite ironic that geographically the Middle East is closest to Europe, yet it was the last region in the world to be colonised by Europeans. Do you think the strength of the Ottoman Empire was the only reason for that?

It was a very important factor. Another is that the Middle East didn’t have a wealth or raw materials to tempt European colonisers, like America or India. That changed with oil.

14- There seems to be a contrast in the style of tolerance given to their subservient rulers by Britain and Russia. So despite being invaded by Russia, Abd al-Ahad (1885-1910) was able to maintain his autonomy since the Russian Foreign Office wanted to keep Bokhara as, in the words of one Russian diplomat, ‘a safety-valve against Muslim discontent with Russian innovations’. The discontented could always migrate from Turkestan to Bokhara, where they could enjoy a traditional way of life under the absolute Emir. This shows the sophistication of Russian foreign policy that seems to have a future vision of creating a sphere of friendly Muslim states allied to them, as the Great Game is played out in these lands with Britain struggling to make headway in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Was this clever politics on the part of the Russians the result of a long term vision and better understanding of these subject populations, or was it merely real-politik?

Russia had been dealing with conquered Muslims since Ivan he Terrible’s conquest of Astrakhan in 1552. I think the Tsarist empire could be quite flexible, and was certainly less rigidly racist than the British.

15- The borders of countries of Middle East were mostly drawn, often to promote British and French interests, as in the case of Iraq, where King Faisal after being installed by the British described himself with resignation as ‘an instrument of British policy’. Do you think the future turmoils in Iraq were partly caused by this outsider being made King, with complete disregard to their own leaders and sensibilities?

King Faisal was a great leader in a difficult position. It is by no means certain local rulers would have done better. Sunnis and Shia also find it difficult to live togehter in the same state in Lebanon and Yemen.

16- In late 1919 and early 1920 there was a reconciliation between the Sultan and the nationalists. The last Ottoman parliament, dominated by nationalists, met at Constantinople rather than Kemal’s base at Ankara. Kemal was restored to his army rank and the Ministry of War resumed its supplies of men and munitions to his forces. However in March 1920 British troops occupied the Ministry of War in Constantinople and in April Damat Ferid returned to power and the Sheikh al-Islam denounced Kemal and his supporters as heretics and rebels. While the Greeks were extending their control of western Anatolia, the Sultan sent forces known as the Armies of the Caliphate against the nationalistic armies. Clearly the British and allies threw their support to a corrupted Sultan who deeply offended the Turks. Was British foreign policy so blind to see the terrible repercussions of this divide and rule policy?

It does seem to have been particularly obtuse, not realising that Britain was undermining its own protege, the Sultan. Some think Britain was deliberately weakening the Caliphate in Turkey at a time when it was the focus of anti-British feeling in India. Britain in Turkey made the characeristic imperialist mistake of overestimating imperial power far from the metropolis – as the US has done in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Both powers also underestimated the desire for peace at home. Power not only corrupts, it also makes rulers blind.

17- Any plans to reprint this book in an expanded version in the future?

One day I would love as there are many collections I have since found and not accessed. Also perhaps to re-print it in a different shape, as has happened with the Turkish edition of this book, recently published by Everest.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer, September 2011.

Yes, I think that is completely correct and it facilitated transport and exchange of people enormously and amongst other things, it revolutionised the Hajj, it made it much easier to get to Mecca. For example pilgrims from Iran could now use the safer and lot quicker sea route via Trabzon or other ports that eventually linked to the Red Sea. And above all, it made it almost certain that Britain would grab Egypt, it made Egypt even more the route to India. Even back during the Indian mutiny Egypt was used as a conduit point to send reinforcement troops to the sub-continent. But other things like the creation of Alexandria and the laying of the Alexandria to Cairo railway were already opening up the Middle East and facilitating exchanges. But the financing of the Suez Canal revealed the folly and extravagance of the Khedive Ismail and the way he fell into debt and under the control of the international financiers. All reminiscent of many Western countries now.

2- The nationalistic revolutions that had the promise of liberation from tyranny in most cases have evolved in to tyrannies of dictators, whether Baath nationalists or Islamists. The Arab Spring is therefore the counter revolution to that. Why do you think it took so long, and do you think these revolutions could also be betrayed by their leaders in time?

As one serving British diplomat recently said to me all revolutions are betrayed. By definition they cannot live up to their citizens’ expectations. But I think there is some hope in Egypt and Tunisia, countries that have a Mediterranean as well as an Arab and Islamic identity. And they took so long because we in England luckily do not - yet - know the paralysing effect of police states, military regimes and fear of prison and torture.

3- Do you think Mohammed Ali, his successor Said Pasha and his successor Khedive Ismail were bound in their quest to free Egypt of Ottoman control to go for modernisation, and in so doing ironically placing their country in danger of increasing debt and British domination?

Yes, I think they were bound to and if the successors had been cleverer British military occupation might have been avoided, or lasted less long (1882-1956). One British official wrote that if the rulers of Egypt had been as sensible as Prince Omar Toussoun, there would have been no ‘Egyptian question’.

4- Would it be extreme to label the significant Levantine merchant community in Egypt and the Ottoman Empire a ‘fifth column’ in European diplomatic manoeuvrings, not by initial design but as a useful tool for foreign powers to use either to gain intelligence or to protect their co-religionists?

Yes, that is completely correct. Although Levantine schools and innovations could encourage local nationalism or progress, individual Levantines in many cases clearly wanted foreign occupation, both in Izmir and in Alexandria. In the latter city, local Greeks gave celebratory balls after the British invasion of 1882. Cavafy’s brothers complained that the British were not sufficiently ruthless in their punishment of Egyptians.

5- The subtitle of the book is ‘Monarchs of the Middle East’, yet amongst those featured are those of Central Asia. Is this because Islamic Central Asia is in your view a partial cultural continnder uation of Arabia?

I put them in because at that time (1988) those areas were under Soviet control. I wanted to remind readers that Bokhara and Kabul once modelled themselves on Istanbul. They were not part of Arabia and were, and again now are, part of the Islamic world.

6- Is it strange that even strong countries with a long serving ruler – for example Iran - also fell into the trap of relying on foreigners for investment, trade concessions and even military protection. Was their historical enmity to the Ottomans part of the reason?

I don’t think it was strange, look at the problems of Greece or Spain today, or the United States today, which also rely on foreign investors and foreign financial markets.

7- The Ottoman Sultan Abdulhamit’s reign is recorded in history as a whole series of negatives, including the use of Kurdish Hamidiye irregulars for atrocities against Armenians. However under him, despite the Caisse de la Dette, which was a vast European-run institution, there was confidence in the system, the government was able to raise new loans and unlike Egypt or Tunisia, this indebtedness never led to foreign control of government. Do you think it a shame the positives of Abdulhamit’s reign have long been over-shadowed with the darker side of his character and regime?

Yes, I would say we tend to forget how much it varied from province to province. Smyrna and Beirut for example experienced a golden age of economic growth and modernisation. By his standards he did his best. But by the end of his absolute rule he no longer had the money to pay his troops. So he wasn’t that much of a success.

8- Understandably the modern Republic of Turkey in its appraisal of history puts a positive spin on the achievements of the Committee of Union and Progress while denigrating the role and actions of the last few Sultans during the early 20th century. Only a few months after the Young Turk revolution in October 1908, Austria annexed Bosnia, followed by the Italian invasion of Libya, the Albanian revolt of 1912 and the first Balkan War in the same year. Do you think official history, even after all this time, needs to rebalance its examination of this disastrous period that was swaying between tyranny and liberalism, but the inexperienced foreign policy of the Young Turks clearly exacted a heavy price on the empire?

I think what is often forgotten are the close links of the CUP with revolutionaries of other nationalities, Greek, Albanian, Armenian. They were completely out of their depth in international diplomacy. Enver Pasha loved war, but was no good at waging it.

9- From the Arabi revolt of 1882 in Egypt and the British intervention it is clear the line of ruling Khedives became more and more impotent in the face of British imperial policy. Abbas Hilmi who reigned from 1892 seems to have been particularly talented yet hamstrung on all quarters. Do you think these Khedives could have played their cards differently to regain Egyptian independence?

No, I think they were more or less powerless. But King Fouad who ruled in 1917-36 did play a clever political game. He was a true Levantine as some of his contemporaries wrote. Expert at political and financial manoeuvres.

10- The book is richly illustrated with photographs of the various Sultans, Princes and Beys of the Middle East. Under strict Islamic interpretation all depictions of faces is considered ‘haram’. Yet some rulers such as Moulay Abdul-Aziz of Morocco practiced it with great enthusiasm. So bending the rules is clearly the prerogative of rulers. However do you think this double-edged sword of self-vanity and love of western innovations made these rulers less popular, weakening their power bases and thus helping the demise of their dynasties?

It is only one Islamic tradition against the representation of the human form. Think of Persian and Ottoman miniatures and Mogul portraits, and the cult of cinema and videos in the modern Middle East. Yes, I think probably the dynasties’ love of modern technology and the changes in their way of life did help to alienate their subjects, as happened with the last Shah of Iran who left in 1979.

11- By the treaty of Fez of 1912 with Morocco, France promised to protect ‘His Sherifian Majesty against all dangers which may threaten his person and his throne’ in return for the right to introduce the ‘administrative, judiciary, scholastic, economic, financial, military reforms which the French government will judge useful’. The Sultan (Moolay Hafid) was reduced to signing the decrees placed before him by the Resident General. Do you think the Sultan and his court fully realised they were giving up their independence when signing this treaty?

I am not certain, but probably they thought they did a good bargain against overwhelming odds. The Moroccan monarchy has lasted longer than the third French Republic which signed this treaty in 1912. Like all the French officers that went round in the 18th century predicting the imminent collapse of the Ottoman Empire but were themselves guillotined in the 1789 revolution.

12- Do you think the Victorians warped view of the moral decay and harem culture of the Middle East helped ease their conscience when they made their moves to colonise these lands.

No, they used real incidents and national conflicts. In some ways in my opinion, they did all too little to change the status of women or slaves. That has come subsequently from the local elites themselves. No Western power that I know of forbade polygamy, unlike for example Kemalist Turkey, and many other independent governments. I would like to say that collecting these photographs and interviewing survivors from these regimes was highly pleasurable. Local libraries in the 1980s were extremely helpful and I had the time of my life interviewing survivors from the reign of King Farouk in London and Paris, Cairo and Istanbul. They were extremely kind and hospitable and despite their years full of joie de vivre. They would have been delighted - and not at all surprised - by the Egyptian revolution of 2011. The tragedy for Egypt is that the politicians, there has been a too long a gap between 1952 and 2011. There are no politicians with experience for the upcoming free elections and party politics.

13- It is quite ironic that geographically the Middle East is closest to Europe, yet it was the last region in the world to be colonised by Europeans. Do you think the strength of the Ottoman Empire was the only reason for that?

It was a very important factor. Another is that the Middle East didn’t have a wealth or raw materials to tempt European colonisers, like America or India. That changed with oil.

14- There seems to be a contrast in the style of tolerance given to their subservient rulers by Britain and Russia. So despite being invaded by Russia, Abd al-Ahad (1885-1910) was able to maintain his autonomy since the Russian Foreign Office wanted to keep Bokhara as, in the words of one Russian diplomat, ‘a safety-valve against Muslim discontent with Russian innovations’. The discontented could always migrate from Turkestan to Bokhara, where they could enjoy a traditional way of life under the absolute Emir. This shows the sophistication of Russian foreign policy that seems to have a future vision of creating a sphere of friendly Muslim states allied to them, as the Great Game is played out in these lands with Britain struggling to make headway in Afghanistan and Central Asia. Was this clever politics on the part of the Russians the result of a long term vision and better understanding of these subject populations, or was it merely real-politik?

Russia had been dealing with conquered Muslims since Ivan he Terrible’s conquest of Astrakhan in 1552. I think the Tsarist empire could be quite flexible, and was certainly less rigidly racist than the British.

15- The borders of countries of Middle East were mostly drawn, often to promote British and French interests, as in the case of Iraq, where King Faisal after being installed by the British described himself with resignation as ‘an instrument of British policy’. Do you think the future turmoils in Iraq were partly caused by this outsider being made King, with complete disregard to their own leaders and sensibilities?

King Faisal was a great leader in a difficult position. It is by no means certain local rulers would have done better. Sunnis and Shia also find it difficult to live togehter in the same state in Lebanon and Yemen.

16- In late 1919 and early 1920 there was a reconciliation between the Sultan and the nationalists. The last Ottoman parliament, dominated by nationalists, met at Constantinople rather than Kemal’s base at Ankara. Kemal was restored to his army rank and the Ministry of War resumed its supplies of men and munitions to his forces. However in March 1920 British troops occupied the Ministry of War in Constantinople and in April Damat Ferid returned to power and the Sheikh al-Islam denounced Kemal and his supporters as heretics and rebels. While the Greeks were extending their control of western Anatolia, the Sultan sent forces known as the Armies of the Caliphate against the nationalistic armies. Clearly the British and allies threw their support to a corrupted Sultan who deeply offended the Turks. Was British foreign policy so blind to see the terrible repercussions of this divide and rule policy?

It does seem to have been particularly obtuse, not realising that Britain was undermining its own protege, the Sultan. Some think Britain was deliberately weakening the Caliphate in Turkey at a time when it was the focus of anti-British feeling in India. Britain in Turkey made the characeristic imperialist mistake of overestimating imperial power far from the metropolis – as the US has done in Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan. Both powers also underestimated the desire for peace at home. Power not only corrupts, it also makes rulers blind.

17- Any plans to reprint this book in an expanded version in the future?

One day I would love as there are many collections I have since found and not accessed. Also perhaps to re-print it in a different shape, as has happened with the Turkish edition of this book, recently published by Everest.

Interview conducted by Craig Encer, September 2011.

Click to read the transcript of interviews with Philip Mansel concerning his later books: ‘Constantinople: City of World’s Desire, 1453-1924’ and ‘Levant: Splendour and Catastrphe on the Mediterranean’.

|

|

Official Tribune at the opening of the Suez Canal. Europeans are clearly in the majority among the Khedive’s guests, as they were among the canal company’s shareholders. The number of European ladies present shows how accessible Egypt had become by 1869.

|

Midhat Pasha was the leading advocate of constitutional reforms, as a minister and, from 1876 to 1877, as Grand Vizir. He was killed on the orders of Abdul Hamid in 1883, when he was living in exile in the Yemen.

|

Mehmed V, who had been kept in seclusion in Dolmabahçe during his brother’s reign, was delighted to replace him in 1909. He was a weak, kind man who preferred poetry to politics.

|

The Opening of the Egyptian Legislative Council, 1914. The Legislative Council, established in 1883, had little power. On the left of the Khedive is the diplomatic corps, including his enemy Kitchener; on the right are court officials. Behind the Khedive are portraits of the Khedive and founder of the dynasty, Mohammed Ali.

|

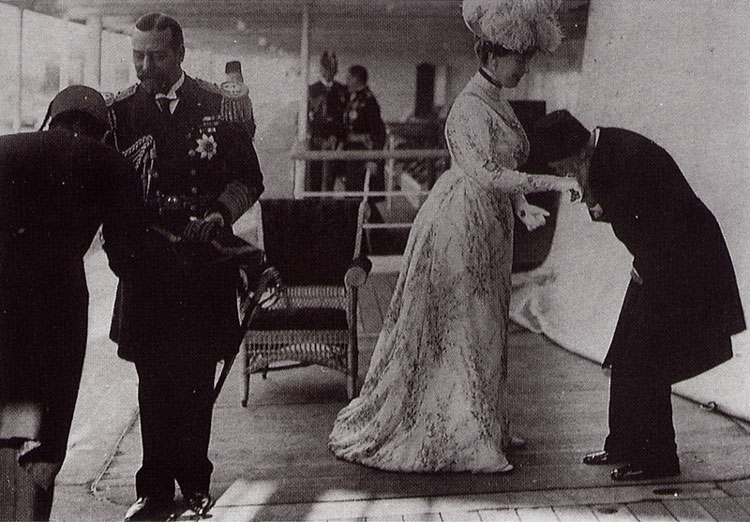

George V and Queen Mary receive the homage of Prince Mohammed Ali (left) and the former Grand Vizir Kiamil Pasha (right). Kiamil Pasha came from English-occupied Cyprus and was so pro-English that he was called English Kiamil.

|

Zill as-Sultan, the Shah’s elder son, was Governor of Isfahan. He wears around his neck the Grand Cross of the Order of the Star of India, a symbol of his pro-British leanings.

|

The installation of Emir Faisal as King of Iraq, Baghdad, 23 August 1921

Left to right: Sir Percy Cox, British High Commissioner; Kinahan Cornwallis; Tahsin Qadri, the King’s ADC; King Faisal; Sir Aylmer Haldane, British commanding officer. The ceremony took place at 6 am because of the heat. Hussein Afnan, secretary of the Council of Ministers, read Sir Percy Cox’s proclamation, which stated that 99% of the country wanted Faisal. Faisal declared ‘the whole nation is my party’. In reality, as the looming British generals and diplomats make clear, it was the British government not the Iraqis which had selected Faisal.

Left to right: Sir Percy Cox, British High Commissioner; Kinahan Cornwallis; Tahsin Qadri, the King’s ADC; King Faisal; Sir Aylmer Haldane, British commanding officer. The ceremony took place at 6 am because of the heat. Hussein Afnan, secretary of the Council of Ministers, read Sir Percy Cox’s proclamation, which stated that 99% of the country wanted Faisal. Faisal declared ‘the whole nation is my party’. In reality, as the looming British generals and diplomats make clear, it was the British government not the Iraqis which had selected Faisal.