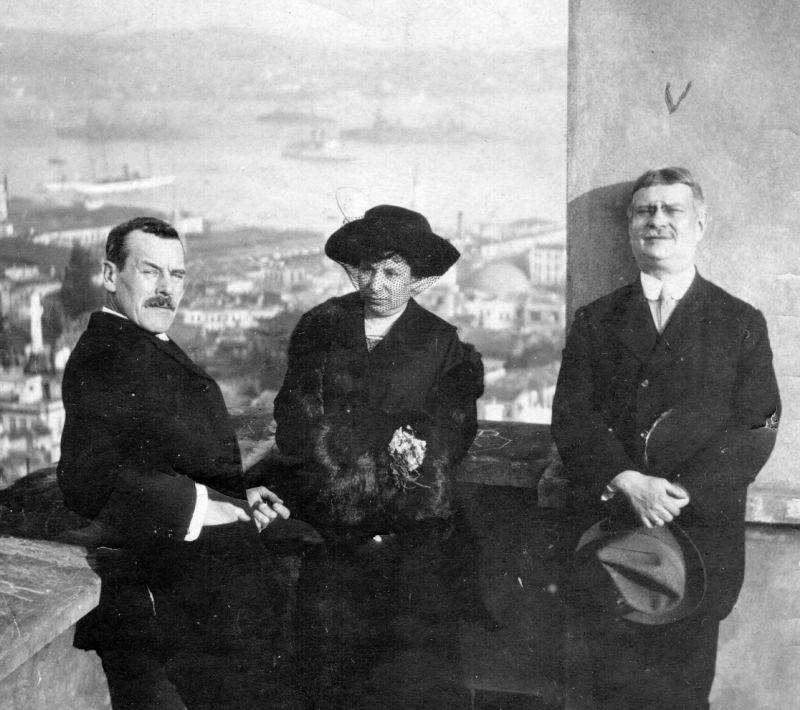

A refugee journey through Ukraine - diary pages about my flight from Constantinople, dedicated to my dear wife Fanny, Dr Friedrich Schrader - published 1919 in Tübingen, Germany - original source in German:

These diary entries are from 3 and 4 November 1918 - Pages 3 and 4 (Translated)

Submission by Jochen Schrader, 2022, grandson of Friedrich Schrader

Once again I noticed, how autumn wrapped its colourful garlands around the cozy nests of the past. I chatted with the common people, men and women, back there in the silent quarters under the city walls. With all of them I noticed an unspoken desire for peace, for liberation from the silent starvation death they were exposed to. I saw the terrible abuse in the food distribution and the appalling injustice against the dispossessed class of non-Muslims, whereas the wealthy elements apparently were pillaged. So we strolled through the horror of the huge fire areas, where the owl nests in the half-burned cypresses and the old wells purl lonely. The faces of my coworkers became darker. More and more openly they expressed their disaffection with our war politics and the necessity of a fast peace settlement.

A creeping fever overcame me, when we worked in the Aksaray quarter on a wet, hot Morning in the ruins of the Indian monastery located there. When I returned on the day of my illness back to Pera, German troops passed by, Artillery, train (transport units on horseback), infantry. Allegedly they were supposed to be moved to the defence of the Tschataldscha-Line, which triggered significant consternation. However, in the electric tram transporting us from Akserai to the Bridge of Karaköj, there were already, a sign of the times, liberated British officers. Already false rumours had spread that British forces had taken position along the border, ready for the invasion. In the days of my illness the rumours about a pending ceasefire agreement based on the blueprint of the Bulgarian ceasefire became stronger and stronger. When I left my home on 2nd of November for the first time after my convalescence, I ran into partying Greeks and Ententists, who celebrated that very ceasefire. General Townshend, the POW of Kut al Amara, had negotiated it. He had been treated in his captivity on Prince's Islands by the Turks with exquisite politeness. In this context I remembered a visit by General Townshend in our editorial offices of the "Osmanischer Lloyd" (Remark: Schrader was deputy editor in chief of that newspaper). The extremely polite and apparently intellectually very capable dry small man had dropped by to receive a cable about the bestowal of a high British Military Order (Remark: the Victoria Cross).

Well, the ceasefire had become reality, and the 19th article of the treaty said: "The German and Austro-Hungarian subjects are to be expelled within a month." So the whole November was spent with a constant struggle to achieve the mitigation or even the annulment of this article. The German Newspaper of Pera, the "Osmanischer Lloyd", under the political direction of W. Feldmann, bravely continued to be published in spite of the increasing difficulties. In those days it became for the sorely afflicted German colony of Constantinople what had been expected from that paper, a faithful consultant and support. But the situation darkened. It became more and more apparent that the Entente believed it should take belated countermeasures against the outrage which had taken place in the Orient, the almost complete annihilation of the Armenian population of Asia Minor. The Admirals of the Entente powers, whose fleets had entered the roadstead of Constantinople on November 12th, on a beautiful, slightly foggy autumn morning, were adamant versus the Germans. They should feel the whole load of the retaliation measures.

20 November 1918, evening.

With a feeling of deep grief I enter my apartment, the place of years of productive work. I sit in my library corner and immerse in reflection. So it shall be over with my research in this beautiful, sunny country (1). The memories of summer mornings in the ruins and orchards of Stambul return to me, the beautiful moments of lucky findings - the silent beautiful sadness of the burned areas with the view into the blue distance of the Anatolian mountains - to the singing sunsets out there at the Byzantine city walls. As with someone who struggles with death and sees the colourful images of his life in one glimpse passing by in quick succession, all these unforgettable visions fly by in front of my eyes.

The doorbell rings - my dear Juana (2) comes back from town. We discuss the situation. - She considers it unworthy that I let myself be detained and urges me to board the "Tiger" (3). She has trust in my luck - a brave little woman. Outside a tropical rain swooshes by and we clench our teeth not to become sentimental in this gray farewell situation. From The Reverend Frew (4) she has obtained the promise to be able to stay in Constantinople, to protect our household and first of all my beloved library, the fruit of years of collection. She is a member of the Anglican Church but did not let that tarnish her incorruptible judgement during the war. She has well recognized the strengths and weaknesses of the German position and follows like myself the same ideal of international justice. So it is decided. Tomorrow I will board the "Tiger".

My suitcases are packed. Now everything left is to say farewell.

6 December 1918, on board the Tigris.

Juana comes on board. She says the Turkish Police has entered the apartments of the Germans at night and has put a number of them, including women and children, on board of the steamer "Corcovado" (5). It did not have the required authority and the order was reversed. But, nevertheless, the German subjects have been kept in captivity. Such a procedure is very much the style of the old Turkish government. They always create "accidental slips", which then create accomplished facts. In the Sublime Porte one is moved by the wish to satisfy the Entente through the most strict execution of Article 19 (6). No consideration that this strictness hits the former Allies, against whom the pro-Entente newspapers "Ieni Istanbul" and "Sabah" rant and curse.

7 December 1918.

Yesterday night I stood in front of the gangway. The sea was silent. Over there the seductive lights of the city were glazing. Below us one could hear rowing strokes. Easy to call a boat and throw myself into it. I literally broke the cordon. I was in Galata in five minutes. With the deerstalker on my head and the pipe in my mouth, which made me look English, I walked up the steep Iüksek Kaldirim to my old home. Juana was visiting friends in Shishli at the end of Pera. I started walking. The electric tram did not run due to a lack of coals. So I walked as "pseudo-Englishman", until I found a car. On the road nothing but Entente troops and subjects of our former enemies. In front of Taxim Gardens a huge number of French trucks were parked. No German face to be seen. Then I stepped in front of surprised Juana, with whom I walked back. On the way we spoke English out of caution.

Footnotes:

(1) Friedrich Schrader (1865-1922) was a German orientalist, university and college teacher, journalist, translator, writer and newspaper editor in Istanbul from 1891 until 1918. He lectured at Robert College and the German School and wrote for leading German newspapers and journals from "Frankfurter Zeitung" to socialist "Die Neue Zeit". From 1908 until 1917 he was founder and deputy editor in chief of German-language daily "Osmanischer Lloyd" in Istanbul. In 1917 Schrader was sacked due to his critical stance towards the German silence on Turkish politics versus non-Muslim minorities.

(2) "Juana" was Schrader's British wife Fanny Goldstein (1874-1919), born in Bogoslov, Bulgaria, member of the Anglican Church.

(3) The "Tiger" was a steamship chartered to evacuate German and axis citizens from occupied Constantinople.

(4) The reverend Robert Frew was the canon of the Archbishop of Canterbury in Constantinople during the war years and himself Canadian of Scottish origin.

(5) The "Corcovado '' was a German ocean liner of HAPAG, which served as the swimming HQ of the German admiralty in Constantinople at the beginning and during the war. After defeat in 1918 German and Axis citizens were detained on the ship.

(6) Article 19 of the ceasefire agreement stated the expulsion of all German and Axis citizens from Allied-occupied Istanbul. (see part 1)

8 December 1918. on board of the "Tigris".

Today the steamer was supposed to leave port. But when Juana came on board at noon time, it was already clear it would not go. Juana brings the good news that she has been able to rent the major part of our apartment to friends of us (3). So her material existence is secured. But what will happen to other remaining German families, who are now stripped of the possibility to make their living without obstructions? Our affairs are being represented by the Swedish embassy. With the well-known humanity and wide-hearted impartiality, with which the Swedish Government is facing the great sufferings of the war, they will surely also take care of our poor German countrymen. But also the help of the Government of the Reich is required. What a pity we do not hear anything any more from them. In our eyes, Germany has completely disappeared behind the thick veils, which the recent sad events have created. Tomorrow night I will go on land again, maybe the last time I will set foot on Turkish soil.

9 December 1918, evening.

This diary entry I once again write in my dear home, sitting at my old, faithful writing desk. At 6 o'clock in the morning I had landed in the cover of darkness down at Galata bridge, arriving with the local steamer from Haidar Pascha. - Everything was still brightly illuminated, so I preferred to walk in the middle of the road. In Malta Road the pubs were full of Levanters, who took their "Aperitif". From "Yüksek Kaldirim" crowds of French "poilus" (remark: front soldiers) came towards me. What a transformation of circumstances in the last three weeks! It started raining. Even the ordure of Galata suddenly became something familiar and dear. Juana waited at the apartment door. The neighbors did not need to sense my presence, because even amongst the best friends there could be some who could not keep their mouths shut. The door closed behind me and once again I enjoyed the sweet delights of home, before I wandered as a refugee out into the horrors of the Russian winter.

10 December 1918

In the afternoon, we (which is Dr Hoffmann, a German Geologist, and myself) stand on the most sacred place in the whole of Constantinople, the British Cemetery of the Fallen of the Crimean War. Under the mighty old conifers there is solemn silence. No human being disturbs my silent meditation. Far out gleams the blue "Propontis" (remark: Sea of Marmara), this sea of indefinite beauty. Over on the other side, at the end of the bay, which forms the shore of Stambul, the towers of Yedikule are rising. Over there, under the protection of the hospitality of Juanas foster mother, lives my 13- year old son, a well-behaved German child, who would have loved so much to accompany me on the dangerous journey ahead (1). We now have to leave this wonderful world behind us and travel out into the nordic freeze and into endless dangers. From the sea blows a light breeze and silently withered leaves and fragrant needles fall towards us. They glide over the mourning figures on the tombstones and the sacred Mausoleum of the former ambassador of His Majesty the King of England at the Ottoman Port, the mild Sir Nicolaus O'Connor (2).

Footnotes:

(1) Ulrich Schrader (1905-1942), son of Fanny Goldstein and Friedrich Schrader. Later lived in Hamburg. During the second world war drafted to work in the arms industry. Died a few months before "Operation Gomorrah", only 38 years of age.

(2) Sir Nicholas Roderick O’Connor (1843-1908) himself Irish and Roman Catholic, was at the time of his death British Ambassador in Istanbul.

(3) The Schraders were living in what is today known as "Dogan Apartmani" in Beyoglu (Pera).