The story of the Barker family

in the Levant, a private study commissioned by Michael Barker

William Barker, youngest son of Thomas Barker, of the Hall,

near Bakewell, Derbyshire, a descendant of an old country family, purchased

an estate in Florida, where he settled only to be compelled to leave during

the American war of Independence. He proceeded to London, en route for

India, but was compelled owing to ill health to break his journey in Smyrna

where he settled and raised a numerous family who have remained firmly

established in various parts of the Levant for nearly two centuries. All

the Barkers hereafter mentioned belong to this family and are descendants

of William Barker, the original settler in Smyrna.

William’s thirteenth child Benjamin Barker (1797-1859) was in Alexandria

during the summer and autumn of 1822, having escaped by a miracle from

the earthquake at Aleppo during which he computed 25,000 lives to have

been lost. William’s great nephew, Charles Piott Barker served in the

Royal Navy at Navarino, 1827. From January 1828 to 1834 he was employed

in a subordinate capacity at the Consulate General in Egypt, and later

held various consular posts in the Turkish Empire. During the Crimean

War he acted as staff interpreter.

Edward Barker (1784-1844) sixth child to William Barker, was Consular

Agent in Cairo for United Kingdom, 21st September 1830 and 17th January

1831, and thereafter Vice-Consul to the 31st March 1834. It shows the

predominance of Italian at that period, as the language of commerce in

the Levant that the letters exchanged between Vice-Consul Barker in Cairo

and Vice-Consul Sloane in Alexandria, both of them of British descent

and background, were exchanged in that language. During Edward Barker’s

period in Cairo the number of British subjects under his care increased

from 200 in 1828 to over 1000 in 1830: well over 90% of this latter figure

were either Maltese or Ionians. In 1831 Edward Barker fled temporarily

from Cairo to Rosetta, where his brother John, the Consul-General (q.v.)

had a house, in order to escape the ravages of cholera. He was in later

life, British Consul at Damascus, and was created a Knight of the Greek

Order of the Saviour.

Edward B. Barker, wrote an account of Consul-General John Barker’s life.

For three years, 1831-4, he acted as Clerk in his father’s office in Alexandria,

and he was for some time the Private Secretary to Consul-General Campbell

(q.v.). In 1836 he was appointed Vice-Consul at Suedia in Syria, and was

subsequently Consul in various parts of the Turkish Empire.

Frederick Peter George Barker (1825-1899), second son of the original

Edward above named, arrived in Alexandria to found the firm Barker &

Co., Shipping Agents in 1845 [an example of a commercial letter a year after]; he was joined shortly afterwards by his

brother Henry Barker (1829-1907) from whom the present Alexandria firm

is descended. Originally in a very small way of business the Barker firm

was not considered worthy of note in the return of British commercial

houses of Alexandria in 1848, and F.P.G. Barker is first mentioned as

a …?… only regular line of steamers trading with Egypt: Burns MacIver

& Co., (the forerunner of the Cunard Line). Agencies followed for

the Wilson and Papyani Lines, and the firm became also large exporters

of cotton seed. On the 10th November 1849 F.P.G. Barker married in Alexandria,

Caroline Lafuente, and in 1880 he and his family moved to Paris where

descendants still exist.

William Burckhardt Barker (1810-1856), son of Consul-General John Barker

and godson of the explorer J.L. Buckhardt was Chancellor of the Cairo

Consulate from May 1831 to July 1832. A member of the Royal Asiatic Society,

he was a well known traveller and a very distinguished linguist acting

as Professor of Arabic, Persian, Turkish and Hindustani for some time

at Eton under Provost Hawtrey. At various times he lived in many different

parts of the Levant. In 1834 he was in business in Beirut; in 1840 he

was appointed Vice-Consul at Tarsus, where he already resided, but not

before some allegations against his character had reached the ears of

Consul General Hodges had to be disposed of. It was Lloyd George’s predecessor

Campbell who had pressed his claims on Palmerston. H.J. Ross met him in

Mosul in December 1847; at the time of his death from cholera during the

Crimean War, he was Chief Superintendent of the British Land Transport

Depot at Sinope. W.B. Barker was regarded as one of the greatest linguists,

oriental and European, of his day, and he published a Turkish grammar,

together with elementary Turkish and Hindi reading books, as well as a

historical work entitled “Lares and Penates: or Cilicia and its Governors”

1853.

Barker, John (1771-1849)

John Barker, the original Barker to establish himself in Egypt, being

appointed British Consul in succession to Peter Lee in 1826, was born

in Smyrna in 1771, and his family were already well known in Egypt which

had been visited by several of his brothers and with whose commerce they

were already concerned prior to his arrival in an official capacity. John

Barker had been educated in England, and at the age of 18 entered the

private banking house of Peter Thelussen in Philpot Lane where he soon

rose to be confidential clerk and cashier. In 1797 he left London as Private

Secretary to John Spencer Smith, British Minister Plenipotentiary [envoy

with full powers] to Sublime Porte [Ottoman Sultan, at the time

being Selim III, reign 1789-1807], brother to Sir Sydney Smith. On

the 9th April 1799 John Barker was commissioned by patent as Pro-Consul

at Aleppo and Agent for the Levant and East India Companies. Thereafter

for the next thirty-three years he was connected with the East India Company.

While at Aleppo he married in 1880, a Miss Hays of that place, who could

already speak five languages fluently at the age of six. By her he had

a numerous and not undistinguished family. On the 18th November 1803 he

became full Consul for the Levant Company, and in the same year he introduced

the practice of vaccination into Asia Minor.

The political difficulties facing him during the Wars of the French Revolution

were considerable, but he always managed to maintain British communications

with India, and the promptitude by which he arranged for the passage of

despatches on one occasion prevented the surrender ..?..

..?.. 1820 he was absent from the Levant visiting France and ..?.. century

the importance of the Levant Company and especially its political privileges

diminished, and accordingly the company surrender its Royal Charter in

1825 with the promise however, that the company’s former servants would

have their rights and privileges guaranteed to them by the British Government.

In the autumn of 1825, therefore, on the death of Peter Lee, Barker was

offered the post of British Consul at Alexandria under Consul-General

Henry Salt, who was already known to him, at least by correspondence.

The appointment was gazetted on the 28th June 1826 and he arrived at his

post on the 26th October of the same year, but he was allowed his salary

of £1000 p.a. from the preceding 5 January, the date on which his

appointment was agreed by both parties. On the death of Henry Salt, Barker

became acting Consul-General October 1827; he was given the substantive

rank of Consul-General for Egypt 7 March 1829 (gazetted 30th June) though

he had earlier been told by the Foreign Office that he could have no hope

of appointment, and he left the country 1st May 1833, being succeeded

as Consul-General by Lt. Col. Patrick Campbell, Barker’s salary as Consul-General

was £1,300 p.a. but he was not appointed Political Agent.

On Barker’s arrival in Egypt in 1826 he found Alexandria still a wretched

town; there was only one very poor hotel, kept by an Italian, and but

two coaches in the place – one belonging to the Viceroy Mohammed Ali,

and the other to his son-in-law Moharrem Bey. A large okel or khan for

the consuls was being built but it took two more years to complete. John

Barker had his first audience with the Viceroy in the 25 November 1826

and was extremely pleased with the attention he received, superior to

those paid to the recently accredited Consul-General of Austria and Sardinia.

From Mohammed Ali’s assertion: ‘I never had a master’ Barker presumed

a reference to the Sultan, and many of Barker’s early despatches are concerned

with the building of Mohammed Ali’s fleet – an obvious threat to the power

of his suzerain. The news of Navarino the Pasha received as a fatalist,

but, in case Great Britain should be at war with the Turks, he promised

in the strongest terms that British subjects would be safe in their persons

and quality: ‘I know well how to appreciate and maintain the reputation

I have acquired for justice and liberality,’ he told Barker, adding that

if the Sultan, as was rumoured, should order a massacre of Christians,

he, the Viceroy, would regard him as an infidel.

Barker considered Alexandria to have a very agreeable and healthy climate,

and to be quite a pleasant place in which to live; it was, however, very

expensive, and he complained that his foreign service allowances were

insufficient. On Chancery business at Alexandria in 1828 he was keeping

four persons at work, eight hours a day except Sunday, and the ensuing

fees were insufficient to meet all the charges. In fact his early relations

with Salt were clouded by a dispute over the appointment of notarial fees

between January 5, 1827, the date of Barker’s nominal appointment, and

October 27, the date when took over effective control of the office. As

a result of the dispute, in which the Foreign Office ruled ..?.. resigned.

Even when ..?.. as Consul General Barker’s allowances as well as his salary

were increased he still found himself in financial difficulties. As a

result he was not surprised with the Viceroy’s pecuniary embarrassment

as with the fact that he could do so much with so little.

The house which Barker took on arrival belonged to Robert Thurburn but,

although he paid £290 a year rent, the rain came through the roof,

and when Lady Georgina Wolff and her baby were staying with them they

had to sleep under the protection of an umbrella – this is the same house

as that in which Consul-General and Mrs. Salt had to sleep under the billiard

table in wet weather.

It was in this house that some ten people of various families died in

1827 and 1828 before it was discovered it was built over some cisterns

or sewers. The garden became the first British Protestant Cemetery in

Alexandria after the death of Consul-General Salt who was buried in it

in1827. Remains and monuments have now been removed to one of the British

Protestant Cemeteries at Chatby, and the former site is now occupied by

a garage and by the grounds of the Armenian Orthodox Cathedral near Rue

Abdel Moneim.

At Alexandria John Barker was kept very busy. He was President of the

European Hospital in 1827; towards its support all ships entering the

harbour paid a fee of $1, and in addition a collection was annually made

among the resident British merchants; on certification of the latter sum

to London an identical amount was subscribed also by the British Government,

thanks to a law of 1826. Accordingly from that date there are annual subscription

lists of Alexandria British residents together with the names of two British

trustees for each year.

In John’s time communications with Europe were improving. In July 1827

John Barker once received a London letter via Paris and Marseilles in

18 days; newspapers often arrived in 20 to 28 days. In 1828 about 800

ships annually entered the harbour of Alexandria, of which an average

of 210 were British or Ionian [islands of Western Greece under British

rule].

After the battle of Navarino (20th October 1827) Barker was in charge

of freeing the Greek slaves in Egypt. Out of 6000, only 400 availed themselves

of his services, and, though the Foreign Secretary, the Earl of Aberdeen,

was very pleased with his efforts when Ibrahim Pasha’s army returned from

the Morea in 1828, 400 Greek women accompanied their Muslim husbands to

Cairo. In the same year the East India Company granted Barker £100

a year as their agent in Egypt, and he moved to a new and much healthier

house in the New Okella near the sea. In 1829 verification of his succession

as Consul-General reached him from Lord Aberdeen, and was delighted to

find that as a mark of approval his allowances were over £400 p.a.

greater than those of Consul-General Salt, who had complained that he

had only some £1,700 all told before paying taxes.

As Consul-General in Egypt, John Barker had to follow the movements of

the Viceroy and had to spend part of each year in Cairo, where he disliked

the dust and heat, much preferred to live in Alexandria. In the summer

of 1829, one of his daughters danced a quad- ..?.. although his relations

with the Viceroy were often strained he nevertheless had a considerable

admiration for him and more especially for his son Ibrahim Pasha. Among

his more distinguished guests, Benjamin Disraeli, the future Prime Minister,

together with his companions Clay and Meredith, the latter of whom, engaged

to Disraeli’s sister, died in Egypt of smallpox, was entertained by him

in 1831. Through Consul Barker, Disraeli had an audience with the Viceroy,

who ever enjoyed European company and information, and with whom Barker

records many hours of interviews. In 1829 Barker computed that the Viceroy

sent between 500,000 and 600,000 dolars as yearly tribute to the Sultan,

yet despite frequent strains in Anglo-Turkish as in Anglo-Egyptian relations,

Barker ever warned Mohammed Ali that any idea of dethroning the Sultan

was a dangerous delusion. He also had to restrain Mohammed Ali from anti-French

activities, and he gladly accepted an obelisk from Karnak as a gift to

Britain, offered because of French pressure for comparable gifts of antiquities.

In 1830 Consul-General Barker was ordered to Cairo on a confidential mission.

Mohammed Ali feared the presence of the French in Algiers; he was worried

lest they should aim at taking over the entire North African coast line,

and when invited to co-operate in this achievement he was very willing

to give way before British warnings. It was on the occasion of this interview

in March 1830 that Mohammed Ali made his famous declaration: “Without

the English for my friends I can do nothing… I foresaw long ago that I

could undertake nothing grand without her permission. Wherever I turn

she is there to baffle me.”

In Alexandria John continued the interest he had shown in Aleppo in the

overland route to India. He encouraged Lieutenant Thomas Waghorn in his

early efforts and sent elaborate answers to a questionnaire from the East

India Company, but long experience made him feel, like Consul-General

Baldwin, a generation earlier, that most of his efforts would be in vain.

John Barker was sympathetic with the Viceroy’s educational efforts, and

in one of his despatches refers to “the Pasha’s of Egypt’s University

at Kasr el Ain near Cairo where 1500 youths are educated at His Highness’

cost.” He followed with interest the achievement of Mohammed Ali in building

an expensive fleet, but in his political conversations with the Viceroy,

despite considerable personal friendship, he could not always free himself

from his Syrian background and prejudices of his early life.

When Salt was seriously ill and dying in 1827 “Mohammed Ali absolutely

refused to communicate with Mr. Barker who unfortunately was obnoxious

to him”, according to Madox, a contemporary traveller. Although Palmerston

enjoyed Barker’s despatches, in which to please the Foreign Secretary

he often enclosed spitefully some of Mohammed Ali’s more oriental remarks,

giving a not altogether fair picture of the Viceroy who had to work with

very unpromising material (see Bowring), nevertheless he was sharply rebuked

from London when he refused to congratulate Mohammed Ali on Ibrahim Pasha’s

victories in Syria and the fall of Acre. Barker tried to counteract the

effect of this criticism by stressing the markedly favourable terms of

a Viceregal document in his favour in regard to his estates in Suedia

..?.. for the use of the phrase ex-Viceroy in his despatches after ..?..

depose his rebellious and overweening vassal. In one of his early despatches,

Campbell, his successor, refers to the bad terms substituting between

Barker and the Pasha. At the same time Barker fell out with the whole

body of British merchants in Alexandria over a case in the consular courts.

A British merchant and a British sea captain were accused of taking a

ship and its cargo out of British jurisdiction though there was a chancery

writ against them. The men were undoubtedly guilty, but Barker acted in

a singularly high-handed manner, imprisoning the two men in his local

consular prison; refusing them bail; and also failing to call in the normal

four assessors at his hearing of the case, at which the evidence though

strong was by no means conclusive; and indeed the law agent to the Foreign

Office doubted the legality of Barker’s action so far outside home jurisdiction.

Unfortunately for Barker the cargo was one of arms, and Mohammed Ali was

very desirous to purchase. Accordingly the British merchants in Alexandria,

practically all of whom were dependent on the Pasha and his monopolies

for a means of livelihood, were practically unanimous in their criticism

of the Consul-General, and in their criticism and unanimity they were

joined by Senior British Naval Officer at port, Captain John Lyons, who

refused to obey Consul-General’s order to convey the prisoners to Malta

en route for England. This was but one of several occasions on which Barker

was at loggerheads either with the officers of the British Navy or with

the British residents.

All in all Barker’s final days in Egypt were clouded by many disagreements.

An honourable, upright and hardworking official, his letters and despatches

show certain disagreeable traits of character. They are at times obsequious

and often self-righteous. He was invariably convinced of his own rectitude

yet accepted reproof with unnecessary humility. Probably he alone was

surprised when orders for his replacement by Colonel Patrick Campbell

arrived early in 1833. The Consul-General Barker as a reward for his long

services to the Levant Company was granted a pension of £400 p.a.

but his expenses in Egypt has so exceeded his income that even when he

had disposed of his summer house at Rosetta and some of his surplus property

in Alexandria, he had still to await the payment of the first quarter

of his retiring allowance before he left in May 1834 to take up his residence

at the property he possessed through his wife’s family at Suedia, about

15 miles from Antioch. There his long-standing friendship with Ibrahim

Pasha was strengthened, and there he cultivated and experimented in one

of the most famous gardens in the middle east, from which he earned the

Gold Medal of the Royal Horticultural Society. He possessed a well furnished

library with regular newspaper files, including “Galignani’s”, “The Illustrated

News”, and “The Constantinople Gazette” according to a passing visitor.

In later years, his son Edward B.B. lived in a small house in the grounds

where he used to prove himself an excellent shot. John Barker died of

apoplexy at his summer house on Mount Rhesus on October 6, 1849 at the

age of 78 and was buried at Bar..?.. published contributions to various

learned journals and the Annual Register of 1818 reprints one of his articles

from the Asiatic Journal.

Foreign Office in Public Records Office. Boase.

Annual Register

Barker, John: Syria and Egypt under the last five Sultans: Being Experiences

during fifty years of Mr. Consul General Barker – 1876 – ed. by Barker,

E.B.B.

Barker, W.B. ed. by Ainsworth, W.F., Lares and Penates, or Cilicia and

its Governors – 1853

Halls, J.J.: Life and correspondence of Henry Salt

St. John, J.A.: Egypt and Nubia under Mohammed Ali

Ross, Janet (ed.) Letters from the East by Henry James Ross, 1837-1857

– 1902

Neale, F.A.: Eight years in Syria, &c. – 1851

Madox, John: Excursions in the Holy Land - 1834

The Alexandria Barkers a short tree

From about 1550 to 1715, four generations living in Darley Dale and Rowsley

Hall, Derbyshire.

John (Rowsley Hall) 1668-1725 m. Catherine Charlesworth

Thomas (Bakewell) 1709-1752 m. Sarah Morris

William (Smyrna) 1738-1825 m. (2nd) Mary Schnell

He was the fourth son and was bought a membership of the Levant Company

and emigrated to Smyrna in 1760.

Edward (Consul in Cairo 1784-1844 Smyrna m. Anna Maria Mavroyanni

Henry 1829-1907 m. Alice Joyce

Henry, with his older brothers and family, moved to Alexandria in 1848

and opened Barker & Co.

Henry Edward KCMG 1872-1945 Alexandria m. Emmeline (Lena) Cornish

Henry Alwyn CBE 1898-1966 Portugal m. Sybil Cumberbatch

Henry Michael 1923- m. (2nd) Kay Seymour

In 1956 all British and French subjects were expelled from Egypt as a

result of the Suez War.

John Barker (1771-1849), Levant Company Consul-General in Aleppo

(1799-1825) and H.M. Consul-General in Alexandria (1826-33)

John Barker was the first of the family to live and work in Alexandria.

William Maltass, married to his half-sister Memica, and John’s younger

half-brother, Edward, were the Consuls in Cairo during the same period:

William Maltass from 1825 to 1829 and Edward from 1830 to 1834.

John’s career has been well recorded and the books (see below) give a

good description of Alexandria and the Levant at that time.

John Barker, born on 9th March 1771, was the fifth child of William and

Flora Robin of Smyrna. His father sent him to his Uncle John at Bakewell

[Derbyshire] for his education. At the age of 18 John entered the private

banking house of Peter Thellussen in Philpot Lane. In 1797 he left London

as Private Secretary to John Spencer Smith, British Prime Minister Plenipotentiary

to the Sublime Porte (Constantinople).

1798, in July Napoleon landed in Egypt.

John describes the discomforts at Constantinople, attendant upon an audience

with the reigning Sultan, even Ambassadors being compelled to wait as

long as four hours before being admitted to the audience chamber and allowed

face-to-face contact with the Sublime Presence:

“I must not omit to mention that when we were standing before the Sultan

there were two colossal negroes, on each side of the throne, the tallest

and ugliest that could be found, making faces – that is, grimaces – at

us, and scowling the whole time, and saying, loud enough to be heard,

Kish: Kish: - which means “drive them out: drive them out”.

In August Nelson destroyed the French fleet at Abukir Bay (Alexandria).

In April 1799 John was commissioned by patent as Pro-Consul and Agent

for the Levant and East India Companies at Aleppo where the widow of the

Consul Robert Abbott who died in 1797 after succeeding David Hays, her

first husband, had been acting for two years.

John held this appointment until the dissolution of the Levant Company’s

charter in 1825.

Aleppo, in Syria, then a province of the Ottoman Empire, was the central

overland staging point between Europe, Basrah and India and an important

trading centre both for the Levant and East India Companies.

On 15th June 1800, John (aged 28) married Marianne (aged 21 or 22) daughter

of the late David Hays at Aleppo: she could speak five languages fluently

by the age of seven. Marianne brought him a sizeable dowry: granddaughter

of Thomas Vernon of Hilton Park “she had a jointure of ten thousand pounds,

placed in the Bank of England by the trustees of her aunt Miss Amelia

Hays’s Will, Sir Charles Pole, Bart and Samuel Bosanquet, Esq., and as

much in jewels and landed property”.

Marianne’s father, David Hays, died (probably from thirst) on the difficult

and dangerous 48 day journey in 1786 from Aleppo to Basrah (Boussorah)

with J. Griffith M.D. who was on his way to India. Marianne then aged

7 or 8, went with them and returned from Basrah under the supervision

of the East India Company representative.

1801, the Marquis of Wellesley wrote to ensure the Consul’s active assistance

for the troops transferring from India to help in the attack on Napoleon

in Egypt.

In September the French were driven out of Egypt by the British (Gen.

Abercrombie) after Napoleon’s three year invasion.

Lord Elgin replaced Sir John Spencer Smith as Ambassador to Turkey.

On 18th November 1803, John became full Consul for the Levant Company,

in the same year introducing the practice of vaccination to Asia Minor.

The potential difficulties facing him during the Anglo-French wars were

considerable but he managed to maintain British communications with India,

and the promptness with which he arranged for the passage of despatches

on one occasion prevented the surrender of Pondicherry to the French.

During the French campaign in Syria he received from the Sublime Porte

a gold medal and a snuff box set in diamonds transmitted by the hands

of his friend Sir Sydney Smith.

Apart from the more serious matters, the function of a British Consul

in the Levant involved attendance at the weddings of his dragomen and

native dependents who are “generally very wealthy merchants, some of them

trading to India, who could load their tables with real silver plate,

and set down one hundred and fifty covers”.

“In summer time, when the marriages generally take place, the courtyards

are illuminated at night with coloured lamps and nightingales in cages

are hired and placed among the shrubs and trees, and sing at intervals

when the music ceases.

The dazzling diamonds of the ladies and the varied colours of their dresses,

the lights, the singing of the birds, the trickling of the water falling

on the marble basins, make one fancy it to be fairyland”.

At celebrities such as these the consumption of tobacco for hookahs, with

food and drink without limit “was equal to a whole year’s average”. Indeed,

so much was spent on marriages that the parties incurred debts which could

not be paid off for a year or two. The time came when “keeping up with

the Jones” assumed such proportions that the Patriarchs and Bishops, alarmed

at this extravagance, called for restraint, fixing the number of days

to be devoted to them and the maximum sum to be expended.

In 1805 Mohammed Ali Pasha was appointed Governor of Egypt by the Sublime

Porte.

Nelson’s victory at Trafalgar is not recorded as having any immediate

or direct impact on their lives.

In 1807 John had to flee from Aleppo owing to the rupture of relations

between England and the Porte, leaving all affairs in the hands of the

Austrian Consul General. The first stop was Lattakia and then by small

boat to Younee after compelling the “rais”(captain) of the boat, at pistol

point, to land their party there instead of Beyrouth.

They rode up to “Dair-el-Kammar”, residence of the Emir of Druse from

where John was able to transmit news to India and then to the sanctuary

of the monastery of Harissa. His family joined him thereafter having escaped

earlier from Aleppo.

The Consul’s return to Aleppo on 2nd of June 1809 was the occasion for

scenes of local splendour.

At this time the French Consul in Aleppo, friend and shooting companion

of John, was Matthieu de Lesseps, father of Ferdinand, creator of the

Suez Canal.

1811, Mohammed Ali Pasha massacred the Mamelukes at the Citadel in Cairo

thus establishing his own rule.

John Barker helped the eccentric Lady Hester Stanhope (1776-1839) from

her arrival in Syria in 1812 with Dr. Meryon, her personal physician,

and time and again tried to restrain “the self-appointed ambassadress

in Syria”.

Barker & Company 1850-1956

The Company was founded in 1850 by Frederick Barker then aged 25 (taking

60 per cent) and his younger brother Harry, aged 21 (40 per cent). Frederick

crossed the Mediterranean to Alexandria from Smyrna after their father

Edward died in 1844; they had both an education in England, spending holidays

with relatives.

The records show that Frederick left Smyrna for Alexandria in about 1846

and worked for a British company until Henry joined him in 1849/50 with

their mother, five sisters aged from 8 to 27 and their two younger brothers

of 18 to 15. Their eldest brother, John, had earlier returned to London

where his unmarried daughter was to provide a holiday home when Henry’s

sons were at school in England.

Their father’s eldest half-brother, John had been Consul General in Alexandria

from 1826 to 1833 retiring to live at Suedieh on the border of Turkey

and Syria until his death in 1849 and their father had held consular posts

both in Cairo and Alexandria. It is probable that the brothers had some

knowledge of, and introductions to, the business community of Alexandria

which was thriving as a result of Mohammed Ali’s reforms and work on the

communications and economic structure of Egypt, in particular the building

of the Mahmoudieh Canal (1819) which joined Alexandria to the Nile. The

Alexandria to Cairo railway was completed in 1851.

The company started as traders, mainly in grain, developing various interests,

including a shipping agency. The accounts for 1857 show that their brother

John in London may have helped with the initial finance. The business

in general necessitated a good working knowledge of several languages

in particular French and Italian. As the company’s interests developed,

regular journeys, usually of two or three months every summer and combined

with family holidays, were necessary to visit principals in Britain and

Europe leaving a trustworthy staff in Alexandria. Trip to Cairo and Suez

(for mail) were also essential: communications were poor and the journey

from Cairo to Suez was on a desert track with occasional rest houses for

travellers using Waghorn’s Overland Route. One night staying in Shepherd’s

Hotel in Cairo, Henry found himself sharing a room with a corpse.

In 1856 letters show Henry played a leading part in protests to the Viceroy,

Mohammed Said Pasha, and the British Consul General, F.E. Bruce, over

a concession (monopoly) given to a towage company for navigation rights

on the Nile and Canals, and the apparent discrimination at that time against

British interests.

In 1857 the company’s capital was £E 5250; net profits were £E

2750 and Henry is shown to have a good taste in cigars. Frederick and

Henry’s mother, Anna, was receiving £E 150/200 a year.

The signatories to commercial protests to the British Consul General in

1864 included Bulkeley, Thurburn, Barker, Fleming, Peel, Moss, Carver,

Joyce and Haselden.

In 1869 Henry’s interests on behalf of Barker and Company were on a broad

scale in the international community. Between 1859 and 1885 he was given

the rank of Consul in Alexandria by Sweden, Norway and Belgium, receiving

decorations from these countries as well as Italy and Turkey itself.

In 1869 the Suez Canal was opened: Henry was there as a guest of the Suez

Canal Company.

Paris was a business outlet at this time for Barker and Co who had a man

from the Alexandria office there in the 1860’s. One, a Mr Hess, being

caught in the city when it was besieged by the Germans in 1870: his letters

sent to Alexandria during the siege left Paris by balloon (balons montes)

are of philatelic interest (Michael has one of these).

In 1872 Frederick and Henry bought a warehouse, shouna Briggs, in the

Minet-el-Bassal area where a Barker company presence was maintained; the

shouna was bombed in the Second World War and finally commandeered as

a school by the Municipality in 1955.

By 1875 a company report shows the agencies held to be Credit Foncier

of England, Burns and McIver’s Cunard Line, Wilson of Hull, Palmer Hall,

Rubattino of Genoa, London and Southwark Insurance, Queen Insurance and

the Maritime Insurance Company. The shipping lines offered called at a

wide range of ports including America, Antwerp, Le Havre, Italy, the Baltic,

Marseilles, Trieste and Bombay. The same report for the month of August

(1875) shows the total export cargoes for the UK in 8 ships to be barley

(1000 tons), wheat (3700 tons), cottonseed (1160 tons), beans (1500 tons),

wool (70 bales), cotton (185 bales), with coal as the bulk import.

The Committee of a Special Commission set up to improve part of the Minet-el-Bassal

area in 1865/1879, includes the name of Carver, Barker and Ralli.

In 1880 Frederick retired from Barker & Company and went to Paris

with his wife Caroline (nee Lafuente), his 19 year old son and daughter

of 14. His son married but had no children; his daughter Marie (Mimi)

married Edouard Jacquemet living in Pau. Marie died in 1959 (aged 93)

leaving many children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren. When Frederick

left, Harry ran the company on his own until joined by his son, Harry,

in 1891 after Harry had spent a period as a cashier in the National Bank

of Egypt.

Over the next ten years, Henry also brought his four younger sons into

Barker and Company after they had worked in other offices, but all four

preferred different occupations. Percy eloped with a French actress and

was cut off financially (dying in Johannesburg in 1898), Oswald joined

the Army and died at the siege of Ladysmith (1900). Godfrey and Cyril

remained with Barker and Company until Henry retired and then travelled

the world as gentlemen of leisure: both joined the Army in the First World

War, Godfrey was at Gallipoli and Cyril in the desert.

The activities of the company continued to be trading in cereals, cotton

seed cake, etc and the ships agency matters.

Various shipping lines had begun using Alexandria and Barker and Company

held the agencies for several based on different UK ports and trades.

In the first years of the new century Sir John Ellerman took over several

of these lines; Leyland becoming Ellerman, Papayanni, Westcott & Lawrence,

Hall, City, Bucknall and the Wilson Line giving a world-wide service.

The ship’s agency work in Alexandria for Ellerman’s was handled by Barker

and Company. Henry at this time arranged for Tamvaco and Olivier nephews

of his wife Alice’s brother, Arthur Joyce, married to Athina Tamvaco,

to share a part of the business: a gesture which was to have difficulties

in the 1950’s.

In 1905 Henry (now 76) retired after 55 years giving Harry the managing

partnership with Harry’s younger brothers, Godfrey and Cyril, as co-partners.

The latter had no inclination for the business and Harry soon bought out

their partnerships. The 1905 balance sheet shows the company capital to

have been £E 35000.

Harry appointed his brother-in-law, Stanley Gordon, as manager. Stanley

developed the business as a shipping agency while Harry promoted, and

was an executive director of some fifteen different companies covering

a wide spectrum of commerce: the National Bank of Egypt (where his brother

in law, Sir Frederick Rowlatt was Governor), the Alexandria Water Company

(built and managed by his father-in-law, J.E. Cornish), land development,

textile factories, Marconi of Egypt (Harry took the first phone call between

Egypt and the UK from his office in Barker and Company), insurance, building,

engineering, and the Minet-el-Bassal Cotton Bourse [exchange].

An interest in the mining of the semi-precious stone, peridot, on the

Red Sea Island of St George provided too many stones and flooded the market.

During the First World War Harry was appointed representative of the British

Ministry of Shipping: he opened and ran from Barker and Company the British

Ministry of Shipping Office from 1914 to 1919 handling all civilian ships

and cargoes for the military forces.

Harry’s son, Alwyn, joined Barker and Company in 1922. Alwyn obtained

two or three commercial agencies, but ships’ matters continued to be the

responsibility of his uncle Stanley Gordon. In 1927 Harry, as the elected

head of the British Community with its resultant responsibilities and

President of the British Chamber of Commerce, was knighted.

At the start of the Second World War in 1939 Harry again became representative

of the British Ministry of Shipping and handled the same responsibilities

from the Barker offices but on a greater scale than he had handled during

the First World War. These included obtaining the services of any civilian

ship as necessary for the war effort: both the Contomichalos and Embiricos

families have stories of their ships being “chartered” by Sir Harry.

In June 1942 Harry was made a Knight Commander of the Order of St Michael

and St George in the June birthday honours. In July Harry, now aged 70,

died; one month after the death of his brother-in-law, Stanley Gordon:

at the time the Germans were at El Alamein, some sixty miles short of

Alexandria.

His son Alwyn who had rejoined the Army in 1939 as Garrison Adjutant and

later became D.A.A.Q.M.G. [district adjutant assistant to the quarter

master general?], Alexandria, was able to resign and take over Barker

and Company where he appointed Tim Ellis as manager.

In 1945 with the War over and British goods in demand, the ships agency

prospered.

In the same year Alwyn set up Barker and Company Cyprus, financed half

by himself and the family subscribing the remainder, to purchase a 1,000

D.W. ton diesel engine ship sunk by a bomb in the harbour of Mombassa

[Kenya]: the “Pahang”, built in Singapore in 1939, was raised, towed to

Suez and finally repaired. The vessel traded on a regular route from Alexandria

to eastern Mediterranean ports and the Black Sea carrying mainly tobacco.

For some years the ship worked well and other, but coal burning, ships

were chartered for the Line. However competition was building up, and

early in 1956, with lack of experience in ship management, the Cyprus

company was on the verge of bankruptcy: the ship was sold with the loss

of the Cyprus company’s capital.

In 1947, Alwyn’s son Michael joined the company. In 1951 Michael was given

a partnership holding of 51 per cent of the shares, Alwyn with 28 and

Beryl, Alwyn’s unmarried sister, with 21 per cent.

In 1950, the company’s centenary year, the agencies held were for Ellermans,

with its Papayanni, Bucknall, City, Hall and Wilson Lines, also the Bank

Line (Andrew Weir), Ben Line (Wm. Thompson), King Line, Bolton Steamship,

Glover Bros, Koninklijke Rotterdam Lloyd, Counties Ship Management (Mavroleon,

Kulukundis), Hull Blyth, S.A.G.A. (Paris), and Patrisanda (Trieste).

In 1952 there was the Revolution and abdication of King Farouk. Business

became more difficult but controllable. The average annual net profit

of the company at this time was about £E 11,000.

In 1955 Michael, with two Egyptian friends formed the Eastern Desert Mining

Company to mine wolfram (tungsten) at Zaarget el Naam (Valley of the Ostriches)

situated in the desert between Assuan and the Red Sea. Preliminary work

showed reasonable results but the prospecting licences were dated August

1956 and only signed in October that year.

In November 1956, as a result of the Suez incident, Barker & Company

was sequestrated and Admiral Yussuf Hammad (ex-Director-General of Ports

and Lights and a friend) appointed as Private Sequestrator. In 1959, in

accordance with the Anglo-Egyptian Agreement of that year, the company

was desequestrated, but the authorities refused to hand the company back

to the Barkers until certain charges incurred during the sequestration

were met: meanwhile the office remained open with the sequestrator in

charge and earned enough to cover staff salaries.

In 1962, the Egyptian Government issued a decree setting up government

shipping agencies and removing agency work from all private companies:

Barker and Company was put into liquidation.

In London the partners had put in a claim for compensation in 1959. This

was settled in 1967. After payment at 50 per cent to all creditors outside

Egypt, the partners received approximately half of the company’s total

value of £100,000 (as assessed and agreed by the British Compensation

Commission): no interest or inflation allowance was agreed.

Michael received compensation for the expenses incurred by the mining

company but not for the concession itself.

In Egypt in 1978, after protracted negotiations with the Egyptian Maritime

Organisation and the payment of all staff redundancy requirements (there

were about 25 persons, one of whom had been with the company for over

30 years), Barker and Company ceased to exist.

Note:

A few years after nationalising shipping agencies under the umbrella of

the National Maritime Organisation, the Government permitted the creation

of private companies, calling themselves Ship Owners Special Representatives,

to handle ships’ matters other than those directly connected with the

movement of a ship in the port and the handling of its cargo.

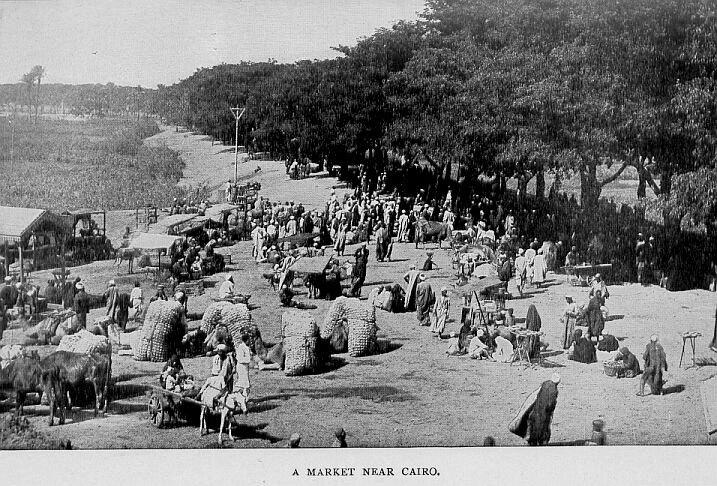

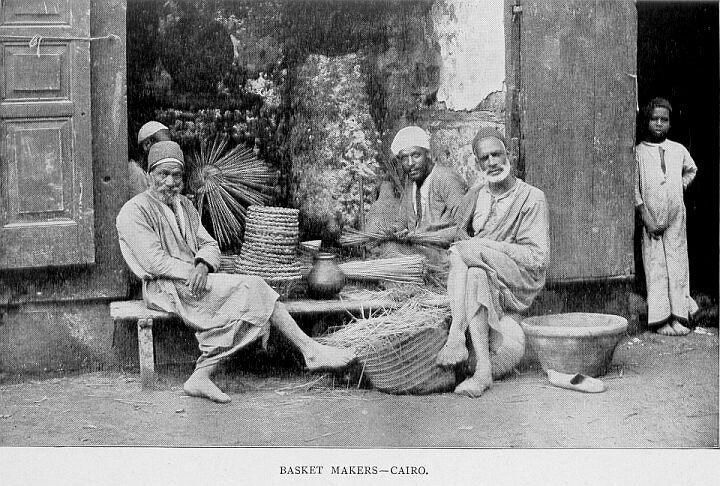

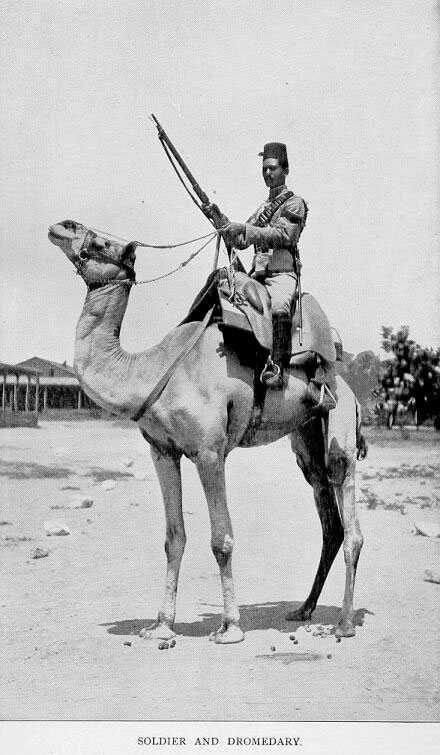

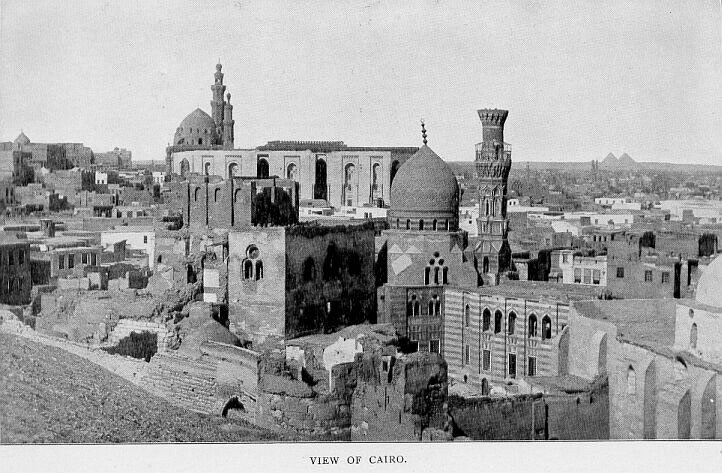

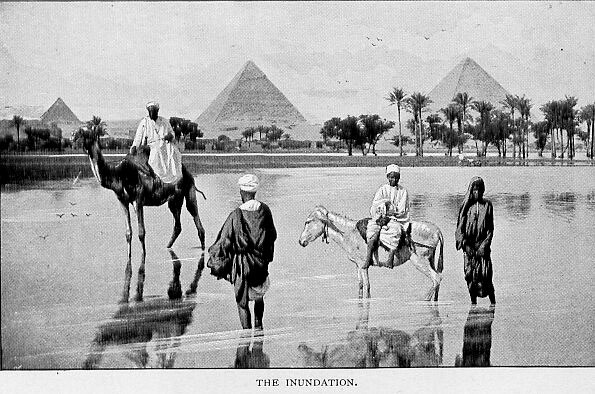

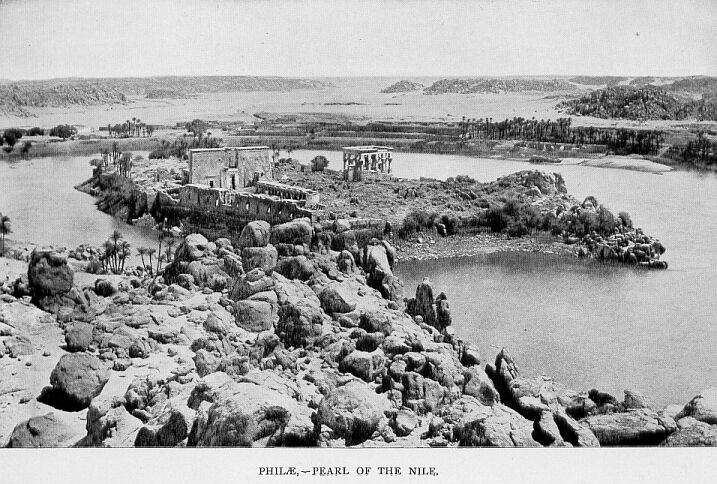

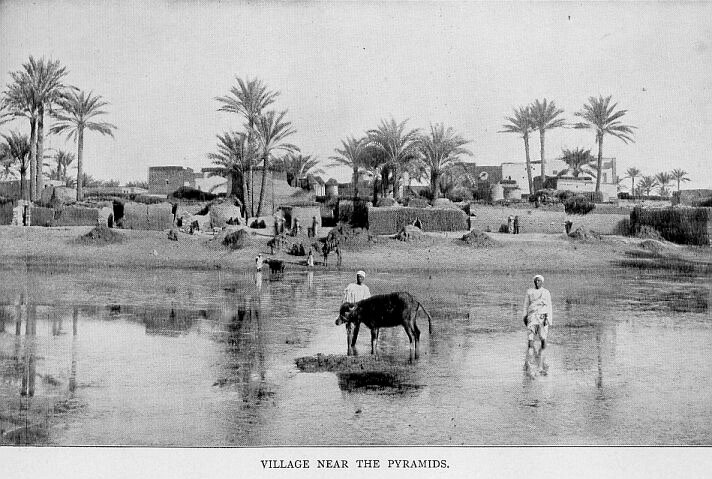

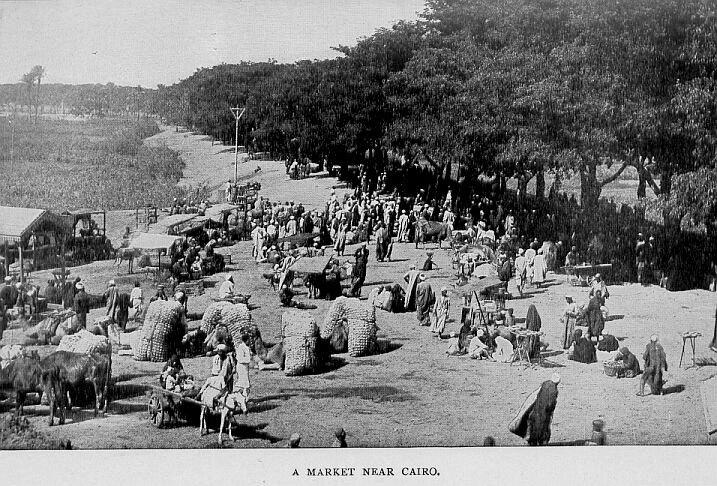

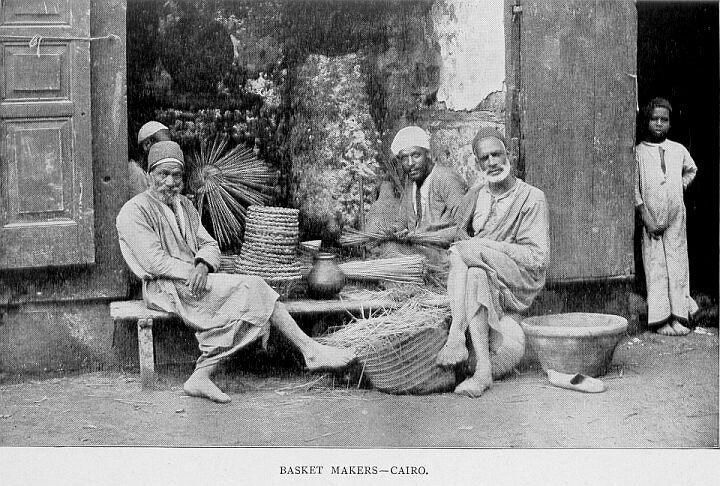

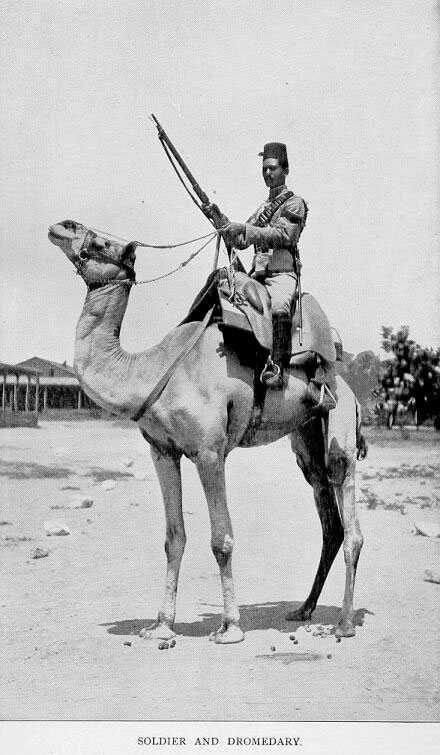

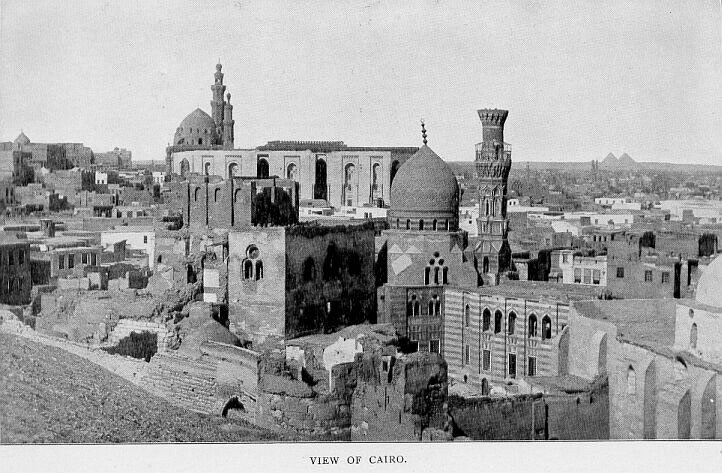

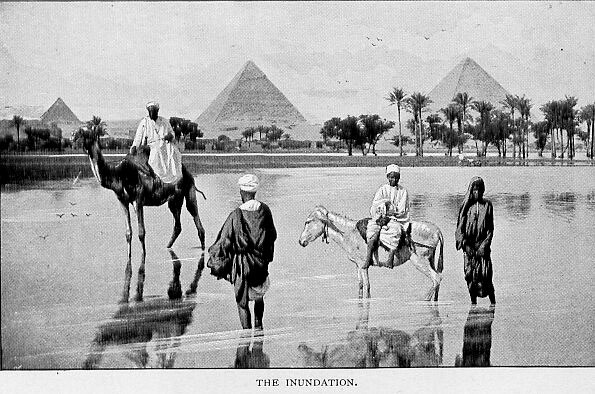

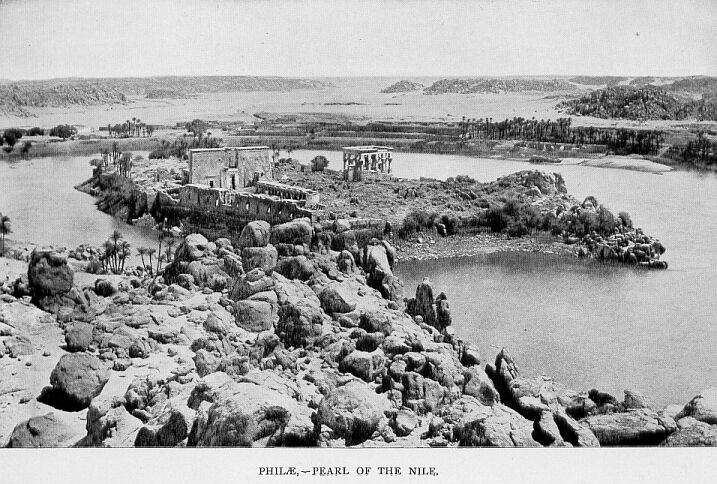

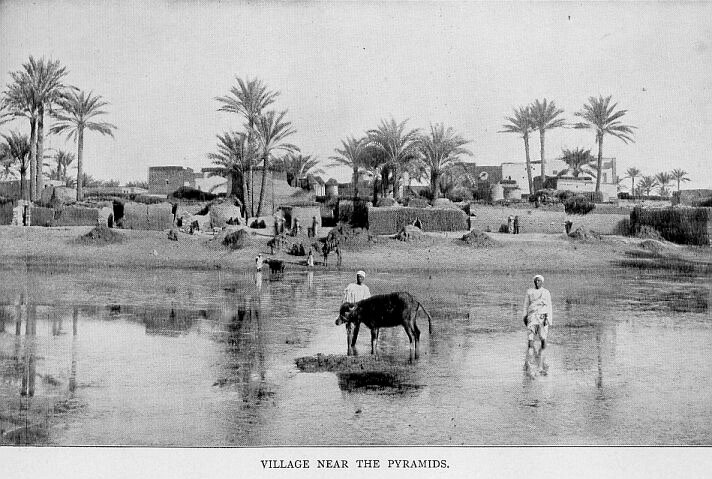

Note: Postcard views (late 19th

century) below are not from the Barker archives, but used to give an impression

of the scenery of Egypt in the past.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|