Introduction

My childhood was spent in what used to be called the Levant, that corner of the ancient world where the sun rose: not Japan or China but the Eastern Mediterranean. Our family house was in Alexandria, still in the 1940’s as much a Greek as an Egyptian city, where every European or Middle Eastern nationality was to be found, and many others besides. No one brought up there spoke fewer than three languages in common currency, Greek, Arabic, French, English and Italian. My father John Rees, who spoke English with a Smyrniot (Greek) accent although he had been to a British public school, was in the shipping business, both as the head of a modest-sized shipping line and as agent for other shipping companies. He was for a long time in partnership with Eugene Eugenidas, who appears in T S Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ as:

Mr Eugenides, the Smyrna merchant

Unshaven, with a pocket full of currants

C.i.f. London

My father was a Smyrna merchant too, born there to a father who had himself been born in Smyrna, modern-day Izmir, and whose father, in turn, had come to Turkey from Wales at the time of the Crimean War in 1853, hoping to make his fortune in the trade of dye-stuffs. My mother was of French stock but similar background. A French ancestor had come to Smyrna before the French revolution of 1789 and his descendants have remained there to this day, trading in every kind of commodity that passed through the most important commercial port of the Eastern Mediterranean for most of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, from the dried raisins and figs for which Smyrna has been famous for centuries to dyestuffs, carpets and cotton textiles. All sorts of European nationalities were incorporated in the two clans in succeeding generations; Austrian, Genoese, Venetian, Dutch, and American. My father’s four brothers married six wives between them; two Greek, a Russian, a Hungarian, a Frenchwoman (my mother) and a solitary Englishwoman.

On both sides of the family there were those who had been Consuls in the cities in which they lived. My first French ancestor, Jean-Baptiste Giraud, an illegitimate son and French royalist who arrived in Smyrna around 1780, was Austrian Consul during the Napoleonic wars and in the last years of the Holy Roman Empire was made a Knight for his services. He married the daughter of the former Venetian Consul, whose city-state had also been extinguished by Napoleon. My earliest British ancestor had arrived in 1793 as Consul for the Levant Company and subsequently became the first British government Consul in Smyrna. His son and grandson were also in the Consular service. My own father was the honorary Consul in Alexandria for both Sweeden and Finland, not because he spoke either Swedish or Finnish (which he didn’t) but because he was the agent for Scandinavian shipping lines whose sailors were in regular need of consular assistance in the port. One brother, Noël, worked under the cover of British Vice-Consul in Smyrna during the Second World War, while running military intelligence operations in the Eastern Mediterranean. Another brother, Willie, was for nearly a quarter of a century Consul-General for Norway in Greece, again because of his personal and family connections with shipping and his own intimate links with business and society in Greece. My family was proud of its consular connections, for in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries the Consuls were effectively the heads of European communities in the different Middle Eastern cities, administering the civil and criminal law as well as representing their countries to the local power, whether Turkish or Egyptian. Wisps of these ancient glories still clung to the consular title, at least in the eyes of their descendants.

Our family house was hung everywhere with portraits from my father’s side of the family; mostly large, severe representations of men in sober costume and full-bottomed wigs, and their modestly but prosperously dressed wives; and of later nineteenth century descendants who dressed with similar restraint. There were a few cheerful exceptions; a be-whiskered Victorian gentelman wearing a top-hat at a rakish angle, who turned out to be my American great-grandfather: a young man in a fine scarlet frock coat and gorgeous waistcoat with a hawk on his wrist, who had gone to Bengal in the 1760’s to make his fortune and like so many others died young of illness while there; and a rather handsome middle-aged man wearing a scarlet military coat and short hair, with a strong but unforbidding face, whose portrait hung above my mother’s desk. This was Captain Francis Werry, Consul for the Levant Company, and great great grandfather to my own grandmother. There were a few Werry relics about our house, mostly in display cabinets which conferred on them a semi-religious status: a gold rattle and coral, with little gold bells and the inscription ‘IW 1710’, which still sits on my dressing table; a letter to Consul Werry from Nelson, and a scrap of Nelson’s breeches, stained with his own blood, taken from his body after his death on the Victory at Trafalgar; a book of letters and documents in fluent but hard to decipher manuscript; a book of memoirs bu another Werry, Consul Werry’s son.

As a child I was properly impressed by these evidences of past glory, but was not sure what they meant. The manuscripts were indecipherable, the memoirs full of contemporary political allusions, to difficult to understand, and the objects themselves unexplained; had my forebear served under Nelson? Why, if he was a sailor, was he wearing a red military coat in his portrait? Who were the severe, be-wigged figures in the dining room portraits, two of them with a little light-house painted in one of the bottom corners of the picture? Had he lived, my father would no doubt have been able to answer these questions, but he died when I was six years old. My mother, who had an encyclopaedic knowledge of the complicated relationships and intermarriages in her vast clan, was vague about my father’s, except where the two clans had mixed - effectively only in the last two generations. My father’s mother, the eldest survivor of the last Werry generation, who was already in her seventies when I was a child, floated serenely in a mental world where myth, history and the supernatural were merged, and her accounts of the past were confusing, if stirring. Her sister, my great-aunt Agnes, was more interested in her dream visitations by the saints and martyrs of Asia Minor than by the history of the more recent past. Surrounded, like her sister, my grandmother, by a horde of cats, dogs, goats - and in the old family house in Turkey by deer, donkeys and poultry as well, the animal kingdom was really more important to both old ladies than the human one.

This introduction serves to explain the exploration that follows of the history of the Werrys and of the Rees family with which they became linked in the latter part of the nineteenth century. It has been pieced together from family records in my possession, from the archives of the Corporation of Trinity House, and from Levant Company and Foreign Office papers in the Public Records Office at Kew; together with some published material available in the British library or more generally. It is not an evenly balanced account. Each generation does not get equivalent coverage. The record is scanty for the earlier generations and what I have written is often speculative. Most of the detailed material in the first part of the book relates either to Consul Werry, and particularly to his time as Consul in Smyrna from 1793 to 1825, or to one of his sons, Francis Peter Werry, who was a junior diplomat during the latter stages of the Napoleonic War, and thereafter at Dresden, the capital of the Kingdom of Saxony. I have written Francis Peter’s story up at some length because his own lively narrative seems to justify it, because he met and worked with some of the great names of the period, including Castlereagh and Wellington, and because he lived through some of the most momentous events of the War, including Napoleon’s invasion of Russia, the events that led up to the Battle of the Nations at Leipzig in 1814, and the Congress of Vienna which laid down the shape of Europe after Napoleon. For three centuries the fortunes of the Werry family were linked with the Levant, in a variety of guises; as masters of trading vessels sailing into Levantine ports for the Levant company, as privateers fighting in the Mediterranean against the French and Spanish who threatened the Levant trade, as consular officials in various countries of the Near East, and as businessmen and proffessionals settled in Turkey.

The second part of the narrative concerns the Rees family who became connected by marriage with the Werry in Turkey in 1889. Theirs is a story much more closely bound up with the nineteenth-century expansion of British political and military power in the Levant, and with the trade that followed the flag. Their rise to riches and subsequent decline mirrors to a large extent the rise and fall of British imperial power in the area, which was able to extract substantial concessions from Turkey in the nineteenth century because of the strength of the British navy; which added Malta and Cyprus to its empire and many of the Greek islands to its sphere of control; and which became in reality, if not in name, the administering colonial power in Egypt and the Sudan. For my parent’s generation, Turkey until the expulsion of the Greeks from Asia Minor in 1923 represented a kind of Arcadia for its physical beauty, its close-knit European society, its freedom, warmth and comfort. Egypt, to which many of them moved from this land of lost content, was by contrast much more urbane, European in tone, modern and sophisticated; and for those who were British, more bound by British hierarchies of class and manners.

Taken as a whole, both parts of this chronicle may serve, I hope, to throw some light on the history of Britain’s engagement with the Near and Middle East at the personal, social and business levels from the eighteenth to the twentieth century. In the process of writing it, it became possible to clear up some of the private puzzles which sparked off the research. The lighthouses in the seventeenth portraits, for example, revealed themselves to be a sign that the sitters were Brethren of the Corporation of Trinity House; the sea-captain wearing a red coat was wearing Consular dress; the manuscripts yielded up their secrets to patient scrutiny. (Though I never did discover the precise route by which the sacred blood-stained scrap of Nelson’s breeches found its way into Consul Werry’s possession).

There are many direct quotations from the text. Most of them come from the memoirs of Francis Peter Werry, and to avoid tedium I have not footnoted all of these. Other references are noted at the end of each chapter.

Tom Rees

January 2003

page 160-161

When war finally broke out between the European powers in August 1914, the Rees family businesses were centred on Smyrna, Alexandria, from which William Rees had recently retired to England, and London, where Tommy Rees’s eldest son John had begun his own independent business as a ship-broker on the Baltic exchange. (His father had vetoed a proposal that he should go from Harrow to university, on the grounds that he would be needed in family affairs). The older Rees children were at boarding school in England, though the younger ones were still at home with their parents in the big house in Boudjah. Although it was clear on which side of the fence Turkey would come down, the Entente Powers (Britain, France and Russia) did not declare war on Turkey until November 1st, after she had closed the Bosphorus straits to allied shipping. This allowed time for the patriotic British subjects in Smyrna to muster a corps of volunteers. At a meeting at the British Consulate on September 25 1914, plans for sending this force to England were agreed. Tommy Rees, ‘un des members les plus marquants de la colonie’ in the words of the ‘Impartial’, put one of his ships at the disposal of the volunteers, and several other members of the British community put up considerable sums of money to assist the cause. As a precautionary move, Tommy Rees embarked his immediate family and that of his sister, Ida Gordon, on his steam yacht the Dragon. The combined party of nine adults and eight children, accompanied by housekeeper, cook and maid, not to mention three pugs and a parrot, sailed for Mytilene (Lesbos) sometime in late August or early September. By December 1914 Tommy Rees was writing to the London office to say that he had taken a house in Greece itself, about three quarters of an hour from Athens, and opened a small office in Athens itself at 46 Stadion Street, ‘so that I feel more comfortable’. Greece remained neutral throughout the war, so that the family was able to stay in the country and the children could continue to attend school in England, even if they could not always easily travel home for the holidays.

For those who did not leave Turkey immediately, no terrible consequences followed. Although Britain was officially at war with Turkey from November onwards, the attitude of the Turkish authorities towards British residents was initially very relaxed. Many of the British, including the Gordons, who lived in the Werry’s old county-house at Boudjah, returned to Smyrna after the initial panic, and did not finally leave until the autumn of 1915. There had been a brief internment of male British subjects during a British bombardment of Smyrna earlier in the year, but the then Governor of Smyrna, Rahmi Bey, had ignored orders from Constantinople to lock them up in the fort, and simply confined them to the big house in Bournabat, an imposing mansion which belonged to the Whittall family. They were out within a few days. Some time in 1914 the Rees house in Boudjah was requisitioned by the then Military Governor, Perter Pasha (believed to be a Pole, and generally held in high esteem by the European Community), who treated the property and its contents with respect. He was reported in the Echo and Evening Chronicle of April 12 1915 to have entertained Sultan Abdul Hamid there when the latter was exiled from Constantinople. Tommy Rees himself, though an enemy subject and official contractor to the British fleet and the French army in the Dardanelles, was not outlawed, nor his property confiscated, until March 1916.

p.200

British weakness was not fully exposed until 1956, however, and in the meantime the Levant, and particularly Egypt, saw a hectic burst of European activity. Large numbers of Allied troops, mostly British, were stationed in Egypt. Refugees from war-zones elsewhere in the West trickled in from a number of destinations, French, Italians, Greeks, Romanians, Yugoslavs, Albanians. Any number of novels and reminiscences of the war and the immediate post-war period were written, of which Olivia Manning’s Levant trilogy and Lawrence Durrell’s Alexandria quartet are perhaps the most famous. The Rees family, present both in Egypt and Turkey, did not play the active entrepreneurial part in the second War that they had taken in the 1914-18 war during the Gallipoli campaign. Their contribution, such as it was, was on the military side, and appropriately enough it was mainly concentrated on the historic Levant territory of Asia Minor and the Greek islands. The two eldest Rees brothers had served in the Navy in the first war, and were too old to fight. They removed for a short while with their families and with their younger brother Willie and his family to the safety of South Africa, where through the agency of John Rees’s business associate, Mr Eugenides, they befriended the exiled Greek royal family, a friendship which in the case of Willie Rees was to continue in the post-war years in Athens. Willie Rees returned to the ranks of the RNVR, where he served as a Lt-Commander in Intelligence, first in Cairo and then after the liberation of Greece, in Athens.

The next brother in line, Noël Carlisle Rees, had an altogether more active and exciting war. In 1939 he was living in Egypt, but spending his summers in Rhodes, where he had built a handsome villa on the sea-shore, from which he would go up into the hills behind to shoot partridge in the aromatic hills and bleached fields of the island. From the terrace of his house he would run the Union Jack up the flagstaff, to the annoyance of the Italian authorities on Rhodes, and the Italian warships that sailed in and out of the bay. In 1940 he was appointed British Vice-Consul and sent, with his wife and small daughter, to the island of Chios, just off the Turkish coast, with responsibility for military and naval intelligence. Noël’s daughter Zoe records that until an assistance arrived to perform the job, she and her mother would help with the code-book to decode the classified signals that arrived in the form of telegrams. Chios was occupied by the Germans in May 1941. By the time the yacht had been requisitioned by the Royal Navy, so Noël and his family had to escape by night in a small fishing boat, a caique, in which they sailed to Turkey, arriving in the little harbour of Çesme. Here they were greeted by the news that a load of wounded British escapers had just arrived from Crete. Noël got hold of motor-boat, crossed back to Chios and collected the wounded men, having taken the precaution of painting his transport in the colours of the Red Cross to protect it against possible German dive-bomber attacks. The boat set course for Alexandria, where it eventually arrived safely, while Noël returned to Turkey.

Once back in Turkey, and inspired by this adventure, he asked the British authorities to let him set up an escape network for allied troops. Commissioned as a Lt-Commander into the RNVR, he was accordingly put in charge of the Turkish operations of N Section of A Force, part of MI9, itself of course part of Military Intelligence. A Force’s job according to MRD Foot, the historian of the British Secret Service operations during the war, was ‘to manufacture strength out of weakness; to organise by every available means the deception of the enemy high command’. N section’s job within this set of goals was to organise the evasion and escaping side of the work. Noël knew the islands well, spoke excellent Greek and was married to a Greek wife. He was made British Vice-Consul in Smyrna, and, making his base in the old Rees family house in Boudjah (where he found on his arrival that his mother had left behind 27 cats and 18 dogs), he set about the establishment of a clandestine naval base at Çesme, just around the corner from the old holiday village of Lidjah, and opposite the island of Chios. The official account of the operation is held in War Office files, now declassified. There it is recorded that he successfully set up a secret operating base at Khioste, near Çesme, a feat involving considerable bribery and personal influence. ‘It was to prove invaluable. From Khioste, caiques were able to proceed to and from the coast of Turkey without let or hindrance. They continued to run throughout the war, in flagrant defiance of all existing laws in Turkey, and those applicable to neutral states. The selection of the peninsula of Çesme was a particularly happy choice in that it was a military area, where unauthorised persons could not proceed without permission, and except under most unusual circumstances, no Germans or Italians succeeded in penetrating the Peninsula throughout the entire war…It is fair to say that this base of Khioste, which was so successfully and amicably shared on an equal basis between MI9 and ISLD during the whole war would never have been established if it had not been for him.’

What the report does not mention is that SOE, the Special Operations Executive, who operated independently in Turkey, had to share the base for a while, and much resented having to work through Noël Rees, who insisted that he should be the sole conduit for communication with the Turkish intelligence authorities. He also resisted all attempts by SOE to turn the base, which was the centre for rescue operations for British and Greek resistance fighters, into an arsenal and sabotage base for SOE. He and the British ambassador in Istanbul feared that Turkish patience would be stretched too far by such an expansion. As it was, during May 1943, the daily number of escapers on the beach at Khioste, mostly Greeks, never fell below 1,500. The Turks had no sympathy with these and, if they intercepted such escapers themselves, normally handed them over to the Germans, who promptly shot them. The official record relates that from December 1941 15,000 Greeks of military age passed through Khioste on their way to refuge in Aleppo, Syria. ‘Of these no less than 12,000 were the direct result of efforts initiated by Lt-Cdr Noël Rees, and his contacts throughout the Aegean islands.’

A radio signals unit was established in another house in Boudjah which had formerly belonged to the Rees family. Noël Rees used his contacts among the Greek fishing communities of the islands to set up a network of caiques for clandestine journeys in the Greek islands. The defeat by the Germans of the British forces occupying Crete in 1941 left some 5,000 troops on the island after the British warships had evacuated as many as they could. According to Foot ‘around a thousand men were taken off Greece and Crete in 1941, either evading capture or escaping from prison, all under the aegis of N section. Some were taken off by submarine, many in little caiques which ploughed to and fro under their Greek captains, often accompanied by Noël Rees himself.’ The traffic was not always one-way. Some of those who had evaded capture were keen to go back into enemy occupied territory for rescue, intelligence or sabotage operations. Until SOE acquired a separate operating base in Cyprus towards the end of 1943 these missions too were organised by N section, again often shepherded to their destination by Noël Rees, whose knowledge of the language and the islands could guarantee their safe arrival and reception.

There was danger not only of a direct kind in this work, from the enemy ships and from the German and Italian garrisons on the mainland of Greece, but also of a more indirect nature. German intelligence was aware of the clandestine British operations in Turkey, and of Noël Rees’s part in them. A report dated 28 September 1942 from Sturmdivision Rhodos, the German intelligence HQ on Rhodes, to the Oberkommando Meeres-gruppe E, responsible for military operations in the Eastern Mediterranean describes British espionage activities in the area. British agents are said to operate mainly from the islands of Simi, Cos, Pserimno and Calino, where living conditions and unemployment make the recruitment of agents relatively easy. Control of their activities is said to be from Turkey, in the hands of the wealthy English merchant Noël Rees, whose villa on Rhodes has been taken over, in his absence, by the Italian secret police. Rees is said to have a wide circle of friends and acquaintances in the island, and three of his agents are identified, controlled probably, according to the report, from the Turkish town of Bodrum. The German authorities in Turkey used what pressure they could to close down Noël Rees’s clandestine naval activities at Çesme, but only succeeded in having them displaced to the safer haven on Khioste. There were dangers too for his family. His wife and daughter had already had to move from the family house in Boudjah because of the presence of a German informer living on the doorstep (actually an elderly Austrian lady who had given piano lessons to children of the family before the war), and the possibility of their being seized as hostages was always present in his mind and that of his staff.

Despite increasing ill-health, which led to his early death from cancer shortly after the War, Noël continued his intelligence role until the collapse of he Italian war effort in the Greek islands, landing on Chios in September 1944 to accept the surrender of the German forces, and joining the staff of General Scobie the following month to take part in the liberation of Athens. This was not an easy or straightforward affair. There was a fierce struggle between, on the one side, the communist guerrillas of ELAS, who tried to seize the capital by force when the Germans retreated, and on the other, the small forces of the Greek Government in exile, aided by a large contingent of British troops, who for a time were surrounded by ELAS in the centre of Athens. Noël’s brother Willie, also on the staff of General Scobie, was holed up with the latter in the unlikely but relatively comfortable surroundings of the Grande Bretagne Hotel during the siege. In an epitaph written by the Times on Noël Rees’s death in 1947, unpublished because of continuing secrecy restrictions on references to the work of the intelligence services, Admiral Lindsay Jackson paid tribute to ‘his first class organising ability and untiring energy’ which had ‘permitted the safe escape of many Britishers and many more Greeks from the Greek mainland and islands’. In one notable case, remembered by Noel’s daughter, an MI6 officer, Frank Mackaskie, who operated out of the base at Khioste, had been caught out of uniform by the Italians and was menaced with a firing squad. Noël Rees is said to have procured the lifting of the death-sentence by interceding with Roncalli, the Papal Nuncio in Istanbul, the future Pope John XXIII, threatening to shoot twenty Italian prisoners of war in retaliation if the execution went ahead. It did not, and Mackaskie subsequently escaped; one of the three successful escapes which this courageous soldier achieved during this period.

In the memoirs of those who knew Noël Rees at the time he is remembered for the style and panache with which his work was conducted and for his hospitality towards those he helped to rescue. The early work of his escape network was funded out of his own pocket, until official funds eventually became available. One escapee from Greece, who managed to land on the Turkish coast and was locked up by the village chief of police, recalled seeing two splendid Rolls Royces sweeping to a halt in a cloud of dust, out of which climbed a smiling gentleman in grey flannels and a Royal Harwich Yacht Club blazer, who clasped his hand enthusiastically in welcome. Another remembered being astonished to find that Levantines were the ‘race of swarthy swollen-nosed gentlemen; a low form of dago’, whom he had expected to be. He was befriended by Noël and Alice Rees and recalled with pleasure the big Italianate house with deer, vineyard and fig trees and the private way to the railway station, where the food was ‘quite excellent’. The décor of antlers and stuffed animals – particularly the bear holding a tray for visiting cards – books, the acres of room, the ballroom all delighted his heart. ‘One might easily have been at home’. It was true, he opined, that the Levantine British seemed to talk with a slight foreign accent, but otherwise they were more British than the British, and produced magnificent teas, cakes, scones, jams and buns (taken from M W Parrish’s book Aegean Adventures, 1993, p.148-9, where it mentions the escapee was Miles Hildyard, who had travelled in a small boat with Michael Parish, both young officers having been wounded, from Crete to Turkey, by a roundabout route through the islands. The journey took three weeks). Nor was it just the British who welcomed and solaced the escaping British soldiers. Bill Giraud was another who lodged and fed many of the newly arrived escapers. (Later he was to be the acting French vice-consul in Smyrna; as in the case of Noël, his real duties were largely to do with intelligence, for which he was in time made a Chevalier in the Légion d’Honneur.) Many were the British officers whom he and his pretty young (second) wife Gwen befriended; one young man was rumoured to have been so smitten with Gwen that he defied his CO’s orders and went AWOL to Smyrna so that he could see her one last time before departing on his next – conceivably last ever – mission. Although Bill was married to a half-English girl and much English was spoken at home, his French, fortunately for his role as French consul, was a great deal better than his father’s, for a good Levantine reason; it was the first language of his mother, who was an Austrian of Italian descent, born in Smyrna.

Noël Rees, however, was ill; sick with a cancer which killed him early in 1947. His elder brothers John and Tommy were also both dead by then, one of a stroke, the other of a congenital heart problem. Of the three, John Rees was the oldest at his death, at 54. The other two were still in their forties. Noël had always, given the chance, taken his share of in running the family business, and applied himself conscientiously, though with failing energies, after his brother John’s death. With his own demise, the business was to flounder. Of the two remaining Rees brothers, only one was still active in business, Willie Rees, who survived in Greece for many years after the war until he and the century were both in their eighties. He had sold his shares in the family shipping business to his eldest brother in a fit of pique after his father’s death and was not able to buy them back when he later repented of his decision. His business interests were many; the principal enterprise among them was the management of the Athens race-course, for which he held the concession, which had to be grimly defended against local intrigues and competition. He also owned and ran a fine racing-stud in the north of Greece, at Lazarina in Thessaly, itself managed by Nat Barker, a cousin, and former commando with a gallant war-time record.

His military career was said by some to have ended in disgrace on the same day that the announcement of his Military Cross came through. Friendlier versions of this tale have his Commanding Officer saying, as he pinned the decoration on his chest: ‘If I had my way, Barker, you’d be facing a Court Martial.’ Commando officers tended to provoke mixed feelings in the bosom of their superiors, and the latter version has a plausible ring to it. By his own account Nat Barker had a rather unconventional attitude to the management of the gold sovereigns entrusted to him for transmission to the Greek guerrillas with whom he liaised, an attitude which they would certainly have understood.

The racing business, which had flourished before the war, was devastated both financially and physically during the years of German occupation, and though it was successfully rebuilt in time, the process was slow, expensive, and demanding of perseverance, moral toughness and diplomatic skill. The last Rees brother Freddie, amiable but not gifted with much business sense, took refuge from the world in his family and in whisky. Their cousins, the two surviving Rees men of that generation, stayed on in Egypt after the war until they were forced out in 1956 with all the other British and French residents. They saw the post-Suez years out with diminished but by no means extinguished resources in Monaco and Paris. In Monte Carlo Basil Rees headed the resident British community, while at his brother’s Parisian breakfast table the champagne bottle continued to salute the day.

For a while the old life revived in Egypt after the war. Business was still good, and the demand for cotton textiles the world over gave a boost to the cotton producing and broking sectors. Oswald Finney, a cotton-broking magnate, and his wife Josa resumed their celebrated annual fancy-dress balls in a mansion hung with Gobelin tapestries and strewn with Fabergé knick-knacks, where the champagne continued to flow and the dancing went on into the morning. Duck shooting on Lake Mariotis, memorably described by Lawrence Durell in the Alexandria Quartet, and perhaps the only unfanciful episode in that highly-coloured work, continued to account for legions of wild duck at the hands of enthusiastic sportsmen in punts. Lord Mountbatten arrived with the British fleet, and danced at a ball at John Rees’s house with John Rees’s widow, now married to Alwyn Barker, the current head of the Barker trading house. In the Nile delta fat little quail, waiting to migrate across the Mediterranean, were shot for Alexandrian dinner-tables and Bobby Locke, the portly South African golfing star, gave a demonstration of professional golf at the Alexandria Sporting Club, dressed in plus-fours with immaculate white knee-socks. The Club also provided the venue for games of polo and rugger, in which the players were mostly drawn from the British armed services, and British troops continued to parade from their barracks behind a drum-major wearing a leopard-skin, though perhaps less frequently or conspicuously than in earlier decades. In the winter the Comédie Française would send a troupe to play in the theatres of Cairo and Alexandria, and there would be visits from the Ballet de Monte-Carlo and that of the Marquis de Cuevas, from the Italian opera, and from French chansonniers like Charles Trenet and Edith Piaf. I have childhood memories of a performance of Porgy and Bess in the early 50s at the Mohammed Ali theatre in Alexandria, which was considered to be rather daring novelty, with black performers in serious operatic roles.

The first serious intimation of the end for the Europeans in Egypt came at the close of 1951 when the Egyptian government under Nahas, having failed to reach a political agreement with Britain, abrogated the 1936 Agreement between the two countries and the condominium in the Sudan. Guerrilla attacks were made on the British base at Ismailia on the Suez Canal. In January 1952, after British retaliatory military action in Ismailia, which led to the death of some fifty Egyptian police, who had been besieged in their barracks by British soldiers, there was serious rioting in Cairo. Famous British landmarks, such as Shepheards Hotel and the Tuft Club, were burned down. So too were shops owned by Italians, Greeks and Jews. It was plain that it was not at the British alone that the anger of the mob was directed, but at the Levantine class as a whole. Later in the same year there was an army coup, led by General Neguib, supported by a group of other officers, among whom the most prominent was Colonel Nasser. King Farouk, unpopular with both Egyptians and Europeans, was exiled. Many of the European residents had for years attempted to insure against the future by transferring capital and assets abroad, but others could not or would not do so, believing that this crisis, like all previous ones, would be surmounted. Some had family or friends overseas. Others, particularly those who had been in Egypt for generations, or who had become British while in Egypt when previously of other nationalities, as for example had many British Jews, had few if any networks of help overseas to which to turn. There was a widespread belief that when push came to shove the British Government would always intervene to ensure its continuing control over the Suez Canal, the lifeline to the Red Sea and India. The British had after all done so many times before; why should they not do so again?

At first, after the army coup, it seemed that changes for the Europeans would after all not be of immense significance. Their taxes might increase; they would have, by degrees, to take on more native Egyptians as employees, as partners or as board members in the Egyptian companies which they controlled; they could expect an unwelcome process of nationalisation of some services, and perhaps a land reform, which would affect the big land owners. European managers were gloomy and pessimistic about the future, but not desperate. In 1953 and 1954 the new government reached agreement with Britain over the outstanding issues of the Sudan and the evacuation of British troops from the Canal Zone, and in 1955 the last British troops left Egypt, leaving behind a European population which felt misgivings but no immediate pressing fears about the future. All this was to change with great rapidity the following year. Political tension between Egypt and the West was already increasing in 1955, the West believing, in an age when the Cold War still dominated international politics, that Egypt was aligning itself with the Soviet bloc. Egyptian politicians for their part perceived Western strategy in the Middle East as designed to isolate Egypt. In 1956 the United States and Britain announced that they would no longer supply the funds for the new High Dam at Assuan, and in retaliation Colonel Nasser, by now President, announced the nationalisation of the Suez Canal and the seizure of the Company’s assets. In the ensuing brief war, France and Britain, abetted by Israel, seized Port Said and set about establishing control over the Canal, in which the Egyptians promptly scuttled ships in order to block the waterway and prevent the passage of oil and troops. The United States and Russia, in a move widely seen as a United States ploy to take over from Britain as the dominant political power in Egypt and the Middle East, brought the action to a rapid halt with an American threat to remove support for the British currency, an act which would have brought Britain to its economic knees. Weakened by it huge war-time debts, principally to the United States, the country no longer had the reserves to stand a run on the pound. Within a short pace of time British, French and Israeli forces had withdrawn, humiliated politically if not militarily. The British Prime Minister, Sir Anthony Eden, was to pay for his failure with an early resignation.

Only days after the withdrawal of the invading forces the British and French communities in Egypt were given their marching orders. Their properties and possessions were sequestrated, and they themselves left with a handful of possessions to find what refuge they could overseas. Michael Barker, grandson of the Harry Barker who had been an associate of Tommy Rees in the early years of the century, was by now running the family firm of Barker and Co. He was given enough money to pay for his family’s passage to Venice, where he was met by Contessa Maggi, an Italian connected in true Levantine style by marriage to the Barkers. They breakfasted together at Harry’s Bar before the family made its way to England. There, in time, the Barkers and other refugees were compensated to some small degree by the government of the country whose political misjudgement had ended generations of involvement in Egyptian affairs. The glory days were finally over. They had been splendid times for those whose affairs had prospered, though by no means all the British in Egypt were wealthy merchants like the Barkers, and the small businessmen, the teachers, the shopkeepers, the civil service pensioners, faced in many cases real hardship. Their departure, and the subsequent disappearance of the main body of Greeks and Italians, profoundly changed the character of Egypt and particularly Alexandria, that most ancient trading city of many faiths and languages. It became within a few years an Arab city, distinctly Egyptian as Algiers is distinctly Algerian, more tolerant in character perhaps than the majority of Arab cities, but with only faint echoes of its past still to be detected in the quarters of the city where its European Levantine population had lived.

For the family whose fortunes we have been following, the Levantine tradition was given its coup de grace by the failed Anglo-French military adventure at Suez. Noel Rees’s daughter Zoe, half Greek herself, kept her father’s house in Rhodes, and spends much of her time there, contributing energetically to Rhodian cultural life, which she has enhanced with a new museum gallery stocked with ancient maps, given in memory of her father and her son. There is a sole descendant of the Rees family on the Greek mainland, but Natasha Clive, Willie Rees’s grand-daughter, married a Greek, and her daughter became Greek at birth. Her distant cousin in Corfu, Piero Carides, descended from the Rees/Cumberbatch line, speaks excellent English and keeps in touch with his British cousins, though purely out of sentiment rather than business – not very Levantine, perhaps. In Turkey the Girauds continue to prosper, bright lights in a European community that is a pale shadow of its former self. Some, in the youngest generation, have married non-Turks, but from Europe or America, not from the Levant. Other Girauds have married Turks, to the dismay of the more conservative of their elderly relatives, and Harry Giraud’s great-granddaughters are reputed to speak Turkish among themselves, even when their Turkish husbands are not present. At a family wedding in the 1970’s more than two hundred relatives from Turkey could be mustered for the ceremony; now it might be a problem to find twenty of European origin from within Turkey itself.

The big family houses of Boudjah and Bournabat, where these survive, now mostly house Turkish institutions – schools, universities, hospitals. Tommy Rees’s house is the centre of a university campus. The antlers and stuffed bear have gone to their long home. For decades of little interest to the Turkish middle-class and the new entrepreneurs, some of the handsome old European houses, with their fine gardens and neo-classical facades, are now being bought and restored by Turks instead of destroyed and re-developed, as was sadly so often the case in the latter part of the twentieth century. In Egypt there is little sign of a similar process; pressure of population and land speculation have in Alexandria led to the disappearance of most of the old villas which adorned not only the suburbs, but the old residential centre, where Sir Henry Barker lived, as well. With or without the houses, the life which animated them largely died, we can now see, with the second War, which exhausted the resources of the main European powers from which the European Levant sprang and which provided its members with essential political and military protection. In an age of nationalism the future of rich foreign minorities in poor countries must always be precarious, and it is a matter of thankfulness that the British and the French Levantines were able to sever their connections with Turkey and Egypt with so little bloodshed and suffering. For that we can thank not only power politics as practiced by the West, but also the relative tolerance of Ottoman Turkey and Khedivial Egypt and their political heirs. Not all withdrawals have been so peaceful, nor their aftermath so imbued, to such a large extent, with goodwill.

|

The house at Boudjah of Thomas Bowen and Ida Josephine Rees (with parasol), 1886.

|

Zoë Rees, nee Werry, 1869-1963, and her ten surviving children; photo taken c. 1915, when the family had taken refuge from Turkey in Athens in the early days of WWI.

Left to right standing: John L. Rees II (1891-1945), Margarey L. Rees (future Mrs Russel) 1892-1974, Thomas B. Rees III (1894-1944), Helene D. Rees (future Mrs Geddes) 1894-1986; sitting, left to right: I. May Rees (future Mrs Mackenzie) 1895-1975, Noël C. Rees (1902-1947), Zoë T. Rees (nee Werry) 1869-1963, William E. Rees (1899-1979), Olivia N. E. Rees (future Mrs Johnston) 1901-1965; front row, left to right: E.M.G. Zoë Rees (future Mrs Mohsen, Mme. Schemeil) 1909-1988, Frederick N.C. Rees (1908-1965).

Left to right standing: John L. Rees II (1891-1945), Margarey L. Rees (future Mrs Russel) 1892-1974, Thomas B. Rees III (1894-1944), Helene D. Rees (future Mrs Geddes) 1894-1986; sitting, left to right: I. May Rees (future Mrs Mackenzie) 1895-1975, Noël C. Rees (1902-1947), Zoë T. Rees (nee Werry) 1869-1963, William E. Rees (1899-1979), Olivia N. E. Rees (future Mrs Johnston) 1901-1965; front row, left to right: E.M.G. Zoë Rees (future Mrs Mohsen, Mme. Schemeil) 1909-1988, Frederick N.C. Rees (1908-1965).

|

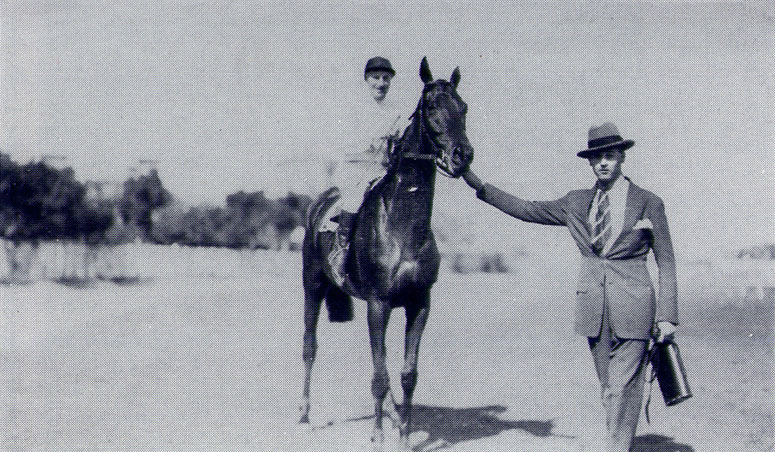

Noël Rees with his race horse Scone in 1930s Alexandria.

|

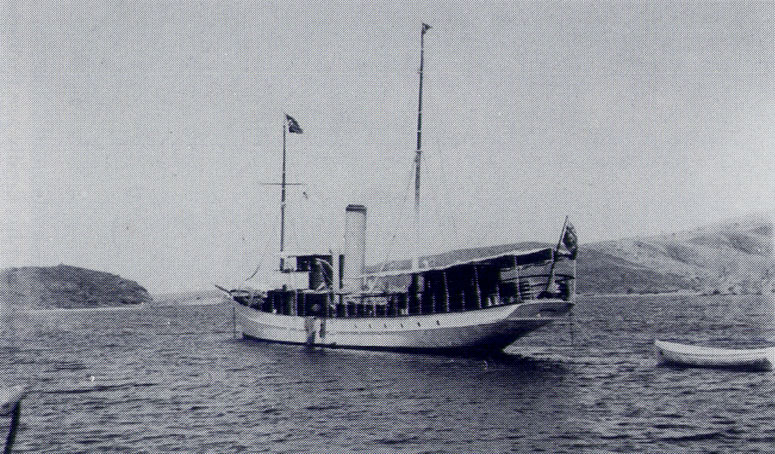

Noël Rees’s yacht, the Branwen, on which he sailed with his family from Italian-controlled Rhodes to Chios in 1940 to take up naval intelligence duties.

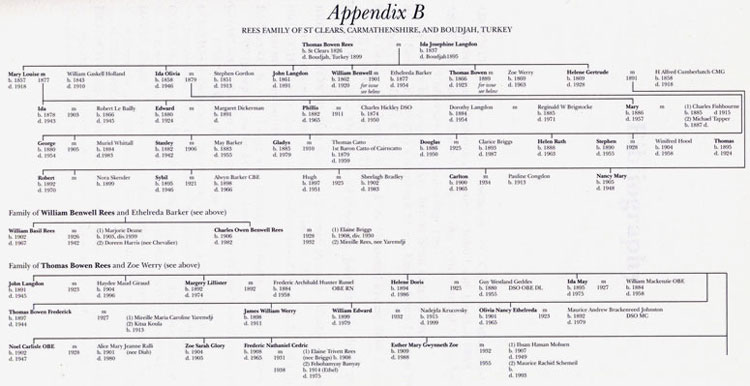

Note: The basic family tree of the Rees family of the Levant, drawn by Tom Rees, son of John Langdon and Haydee Maud (nee Giraud) Rees.

|